AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

John W. Addison

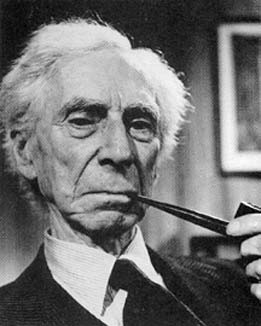

Bertrand Arthur William Russell

1872-1970

The Daily Princetonian [Princeton University], Friday, November 11, 1950, p. 1, col. 1. Addison, now Professor Emeritus of Mathematics, University of California at Berkeley, is a member of Princeton University’s Class of 1951. In an interview, Albert Tucker, Addison’s advisor, recalls how his protégé declared mathematics as his major “in despera-tion” (to avoid a cumulative fine imposed on late declarers), but soon after came under the spell of mathematician and logician (and devout Presby-terian) Alonzo Church, eventually marrying his daughter. I post this story for its historical and human interest only, not in any way to express interest in the “hypothesis” that Russell offered.

Anthony Flood

March 2, 2013

Russell Explains Mind and Matter Are Same Thing

John W. Addison, Jr.

Speaking only a few hours after the announce-ment that he had been awarded the 1950 Nobel Prize in literature, the great philosopher Bertrand Russell last night celebrated the high honor with a brief presentation of his theory of neutral monism before a record overflow crowd of 800 in McCosh 50.

With a clarity of style and a sparkling humor uncharacteristic of most great men invited to lecture at Princeton, the 78-year-old British earl gave in his 55-minute talk one resolution of a problem that has puzzled the philosophers of all time—whether matter is dependent on mind or mind on matter. His answer was simple—mind and matter are actually almost the same thing, so there isn’t any real problem after all.

An audience that fought for seats 15 minutes before the speech began and which included Albert Einstein among many intellectual dignitaries, stood up in a powerful gesture of applause when Professor Robert M. Scoon, chairman of the Department of Philosophy, announced that Lord Russell had just been awarded the Nobel Prize. Grey-haired but very sprightly, Russell nodded his thanks and gestured to Einstein when he recognized him among the crowd.

Russell first explained the classical problem behind his topic of “Mind and Matter,” and then offered his hypothesis that mind and matter both are series of events, and that the only difference between them lies in the arrangement of the events within the series.

Starting with an analysis of the famous statement of Descartes, who by the end of the evening was seemingly utterly disintegrated, that “I think,-therefore I am,” Russell noted that “it would be indeed difficult to pack so many profound errors into another statement of so few words.”

Russell explained that whereas we can know of matter only as the “somewhat uncertain relation of events which lead from a hypothetical maze of quantum transitions, through energy releases, to an effect on the optic nerves, it would certainly be presumptuous to say that the mind was something entirely different.” In fact, he suspects that the brain and the mind are actually both groupings of the same events, with a different arrangement being given depending on whether you are looking at the matter through the laws of physics or those of psychology.