AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

Greg L. Bahnsen

1948-1995

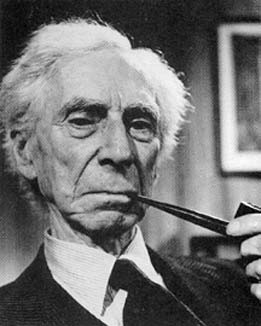

Bertrand Arthur William Russell

1872-1970

I supplied the title to this excerpt from a chapter in Bahnsen's Always Ready: Directions for Defending the Faith, Covenant Books, 1996.

Anthony Flood

August 31, 2009

Firing an Unloaded Gun: Bertrand Russell on Christianity

Greg L. Bahnsen

An excellent opportunity to practice our defense of the Christian faith is provided by one of the most noteworthy British philosophers of the twentieth century: Bertrand Russell. Russell has offered us a clear and pointed example of an intellectual challenge to the truthfulness of the Christian faith by writing an article which specifically aimed to show that Christianity should not be believed. The title of his famous essay was “Why I Am Not a Christian.”1 Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) studied mathematics and philosophy at Cambridge University and began his teaching career there. He wrote respected works as a philosopher (about Leibniz, about the philosophy of mathematics and set theory, about the metaphysics of mind and matter, about epistemological problems) and was influential on twentieth-century developments in the philosophy of language. He also wrote extensively in a more popular vein on literature, education and politics. Controversy surrounded him. He was dismissed by Trinity College for pacifist activities in 1916; he was jailed in 1961 in connection with a campaign for nuclear disarmament. His views on sexual morality contributed to the annulment of his appointment to teach at the City University of New York in 1940. Yet Russell was highly regarded as a scholar. In 1944 he returned to teach at Cambridge, and in 1950 he became a recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

For all his stature as a philosopher, Russell cannot be said to have been sure of himself and consistent in his views regarding reality or knowledge. In his early years he adopted the Hegelian idealism taught by F. H. Bradley. Influenced by G. E. Moore, he changed to a Platonic theory of ideas. Challenged by Ludwig Wittgenstein that mathematics consists merely of tautologies, he turned to metaphysical and linguistic atomism. He adopted the extreme realism of Alexius Meinong, only later to turn toward logical constructionism instead. Then following the lead of William James, Russell abandoned mind-matter dualism for the theory of neutral monism. Eventually Russell propounded materialism with fervor, even though his dissatisfaction with his earlier logical atomism left him without an alternative metaphysical account of the object of our empirical experiences. Struggling with philosophical problems not unlike those which stymied David Hume, Russell conceded in his later years that the quest for certainty is a failure.

This brief history of Russell’s philosophical evolution is rehearsed so that the reader may correctly appraise the strength and authority of the intellectual platform from which Russell would presume to criticize the Christian faith. Russell’s brilliance is not in doubt; he was a talented and intelligent man. But to what avail? In criticizing Christians for their views of ultimate reality, of how we know what we know, and of how we should live our lives, did Bertrand Russell have a defensible alternative from which to launch his attacks? Not at all. He could not give an account of reality and knowing which—on the grounds of, and according to the criteria of, his own autonomous reasoning—was cogent, reasonable and sure. He could not say with certainty what was true about reality and knowledge, but nevertheless he was firmly convinced that Christianity was false! Russell was firing an unloaded gun.

Bertrand Russell made no secret of the fact that he intellectually and personally disdained religion in general, and Christianity in particular. In the preface to the book of his critical essays on the subject of religion he wrote: “I am as firmly convinced that religions do harm as I am that they are untrue.”3 He repeatedly charges in one way or another that a free man who exercises his reasoning ability cannot submit to religious dogma. He argued that religion was a hindrance to the advance of civilization, that it cannot cure our troubles, and that we do not survive death.

We are treated to a defiant expression of metaphysical materialism—perhaps Russell’s most notorious essay for a popular reading audience—in the article (first published in 1903) entitled “A Free Man’s Worship.” He there concluded: “Brief and powerless is man’s life; on him and all his race the slow, sure doom falls pitiless and dark. Blind to good and evil, reckless of destruction, omnipotent matter rolls on its relentless way.” In the face of this nihilism and ethical subjectivism, Russell nevertheless called men to the invigoration of the free man’s worship: “to worship at the shrine that his own hands have built; undismayed by the empire of chance . . . .”3

Hopefully the brazen contradiction in Russell’s philosophy of life is already apparent to the reader. He asserts that our ideals and values are not objective and supported by the nature of reality, indeed that they are fleeting and doomed to destruction. On the other hand, quite contrary to this, Russell encourages us to assert our autonomous values in the face of a valueless universe—to act as though they really amounted to something worthwhile, were rational, and not merely the result of chance. But after all, what sense could Russell hope to make of an immaterial value (an ideal) in the face of an “omnipotent matter” which is blind to values? Russell only succeeded in shooting himself in the foot.

The essay “Why I Am Not a Christian” is the text of a lecture which Russell delivered to the National Secular Society in London on March 6, 1927. It is only fair to recognize, as Russell commented, that constraints of time prevented him from going into great detail or saying as much as he might like about the matters which he raises in the lecture. Nevertheless, he says quite enough with which to find fault.

In broad terms, Russell argued that he could not be a Christian because:

(1) the Roman Catholic church is mistaken to say that the existence of God can be proved by unaided reason;

(2) serious defects in the character and teaching of Jesus show that he was not the best and wisest of men, but actually morally inferior to Buddha and Socrates;

(3) people accept religion on emotional grounds, particularly on the foundation of fear, which is “not worthy of self-respecting human beings”; and

(4) the Christian religion “has been and still is the principal enemy of moral progress in the world.”

What is outstanding about this litany of complaints against Christianity is Russell’s arbitrariness and inconsistency. The second reason offered above presupposes some absolute standard of moral wisdom by which somebody could grade Jesus as either inferior or superior to others. Likewise, the third reason presupposes a fixed criterion for what is, and what is not, “worthy” of self-respecting human beings. Then again, the complaint expressed in the fourth reason would not make any sense unless it is objectively wrong to be an enemy of “moral progress”; indeed, the very notion of moral “progress” itself assumes an established benchmark for morality by which to assess progress.

Now, if Russell had been reasoning and speaking in terms of the Christian worldview, his attempt to assess moral wisdom, human worthiness, and moral progress—as well as to adversely judge shortcomings in these matters—would be understandable and expected. Christians have a universal, objective and absolute standard of morality in the revealed word of God. But obviously Russell did not mean to be speaking as though he adopted Christian premises and perspectives! On what basis, then, could Russell issue his moral evaluations and judgments? In terms of what view of reality and knowledge did he assume that there was anything like an objective criterion of morality by which to find Christ, Christians, and the church lacking?

Russell was embarrassingly arbitrary in this regard. He just took it for granted, as an unargued philosophical bias, that there was a moral standard to apply, and that he could presume to be the spokesman and judge who applies it. One could easily counter Russell by simply saying that he had arbitrarily chosen the wrong standard of morality. To be fair, Russell’s opponents must be granted just as much arbitrariness in choosing a moral standard, and they may then select one different from his own. And there goes his argument down in defeat.

By assuming the prerogative to pass moral judgment, Russell evidenced that his own presuppositions fail to comport with each other. In offering a condemning value-judgment against Christianity, Russell engaged in behavior which betrayed his professed beliefs elsewhere. In his lecture Russell professed that this was a chance world which shows no evidence of design, and where “laws” are nothing more than statistical averages describing what has happened. He professed that the physical world may have always existed, and that human life and intelligence came about in the way explained by Darwin (evolutionary natural selection). Our values and hopes are what “our intelligence can create.” The fact remains that, according to “the ordinary laws of science, you have to suppose that human life . . . on this planet will die out in due course.”

This is simply to say that human values are subjective, fleeting, and self-created. In short, they are relative. Holding to this kind of view of moral values, Russell was utterly inconsistent in acting as though he could assume an altogether different kind of view of values, declaring an absolute moral evaluation of Christ or Christians. One aspect of Russell’s network of beliefs rendered another aspect of his set of beliefs unintelligible.

The same kind of inner tension within Russell’s beliefs is evident above in what he had to say about the “laws” of science. On the one hand such laws are merely descriptions of what has happened in the past, says Russell. On the other hand, Russell spoke of the laws of science as providing a basis for projecting what will happen in the future, namely the decay of the solar system. This kind of dialectical dance between conflicting views of scientific law (to speak epistemologically) or between conflicting views of the nature of the physical cosmos (to speak metaphysically) is characteristic of unbelieving thought. Such thinking is not in harmony with itself and is thus irrational.

In the first reason given by Russell for why he was not a Christian, he alluded to the dogma of the Roman Catholic church that “the existence of God can be proved by the unaided reason.”4 He then turns to some of the more popular arguments advanced for the existence of God which are (supposedly) based upon this “unaided reason” and easily finds them wanting. It goes without saying, of course, that Russell thought that he was defeating these arguments of unaided reason by means of his own (superior) unaided reason. Russell did not disagree with Rome that man can prove things with his “natural reason” (apart from the supernatural work of grace). Indeed, at the end of his lecture he called his hearers to “a fearless outlook and a free intelligence.” Russell simply disagreed that unaided reason takes one to God. In different ways, and with different final conclusions, both the Roman church and Russell encouraged men to exercise their reasoning ability autonomously—apart from the foundation and restraints of divine revelation.

The Christian apologist should not fail to expose this commitment to “unaided reason” for the unargued philosophical bias that it is. Throughout his lecture Russell simply takes it for granted that autonomous reason enables man to know things. He speaks freely of his “knowledge of what atoms actually do,” of what “science can teach us,” and of “certain quite definite fallacies” committed in Christian arguments, etc. But this simply will not do. As the philosopher, Russell here gave himself a free ride; he hypocritically failed to be as self-critical in his reasoning as he beseeched others to be with themselves.

The nagging problem which Russell simply did not face is that, on the basis of autonomous reasoning, man cannot give an adequate and rational account of the knowledge we gain through science and logic. Scientific procedure assumes that the natural world operates in a uniform fashion, in which case our observational knowledge of past cases provides a basis for predicting what will happen in future cases. However, autonomous reason has no basis whatsoever for believing that the natural world will operate in a uniform fashion. Russell himself (at times) asserted that this is a chance universe. He could never reconcile this view of nature being random with his view that nature is uniform (so that “science” can teach us).

So it is with a knowledge and use of the laws of logic (in terms of which Russell definitely insisted that fallacies be avoided). The laws of logic are not physical objects in the natural world; they are not observed by man’s senses. Moreover, the laws of logic are universal and unchanging—or else they reduce to relativistic preferences for thinking, rather than prescriptive requirements. However, Russell’s autonomous reasoning could not explain or justify these characteristics of logical laws. An individual’s unaided reason is limited in the scope of its use and experiences, in which case it cannot pronounce on what is universally true (descriptively). On the other hand, an individual’s unaided reason is in no position to dictate (prescriptively) universal laws of thought or to assure us that these stipulations for the mind will somehow prove applicable to the world of thought or matter outside the individual’s mind.5

Russell’s worldview, even apart from its internal tensions, could not provide a foundation for the intelligibility of science or logic. His “unaided” reason could not account for the knowledge which men readily gain in God’s universe, a universe sovereignly controlled (so that it is uniform) and interpreted in light of the Creator’s revealed mind (so that there are immaterial laws of thought which are universal).

We must note, finally, that Russell’s case against being a Christian is subject to criticism for its reliance upon prejudicial conjecture and logical fallacies. That being the case, he cannot be thought to have established his conclusions or given good reason for his rejection of Christianity.

One stands in amazement, for instance, that the same Russell who could lavish ridicule upon past Christians for their ignorance and lack of scholarship, could come out and say something as uneducated and inaccurate as this: “Historically it is quite doubtful whether Christ ever existed at all, and if He did we do not know anything about Him.” Even forgetting secular references to Christ in the ancient world, Russell’s remark simply ignores the documents of the New Testament as early and authentic witnesses to the historical person of Jesus. Given the relatively early dates of these documents and the relatively large number of them, if Russell “doubted” the existence of Jesus Christ, he must have either applied a conspicuous double standard in his historical reasoning, or been an agnostic about virtually the whole of ancient history. Either way, we are given an insight into the prejudicial nature of Russell’s thinking when it came to consideration of the Christian religion.

Perhaps the most obvious logical fallacy evident in Russell’s lecture comes out in the way he readily shifts from an evaluation of Christian beliefs to a criticism of Christian believers. And he should have known better. At the very beginning of his lecture, Russell said, “I do not mean by a Christian any person who tries to live decently and according to his lights. I think that you must have a certain amount of definite belief before you have a right to call yourself a Christian.” That is, the object of Russell’s criticism should be, by his own testimony, not the lifestyle of individuals but the doctrinal claims which are essential to Christianity as a system of thought. The opening of his lecture focuses upon his dissatisfaction with those beliefs (God’s existence, immortality, Christ as the best of men).

Nevertheless, toward the end of his lecture, Russell’s discussion turns in the direction of fallaciously arguing against the personal defects of Christians (enforcing narrow rules contrary to human happiness) and the supposed psychological genesis of their beliefs (in emotion and fear). That is, he indulges in the fallacy of arguing ad hominem. Even if what Russell had to say in these matters was fair-minded and accurate (it is not), the fact would remain that Russell has descended to the level of arguing against a truth-claim on the basis of his personal dislike and psychologizing of those who personally profess that claim. In other settings, Russell the philosopher would have been the first to criticize a student for pulling such a thing. It is nothing less than a shameful logical fallacy.

Notice briefly other defects in Russell’s line of thinking here. He presumed to know the motivation of a person in becoming a Christian—even though Russell’s epistemology gave him no warrant for thinking he could discern such things (especially easily and at a distance). Moreover, he presumed to know the motivation of a whole class of people (including those who lived long ago), based on a very, very small sampling from his own present experience. These are little more than hasty and unfounded generalizations, telling us (if anything) only about the state of Russell’s mind and feelings in his obvious, emotional antipathy to Christians.

But then this leaves us face to face with a final, devastating fallacy in Russell’s case against Christianity—the use of double standards (and implicit special pleading) in his reasoning. Russell wished to fault Christians for the emotional factor in their faith-commitment, and yet Russell himself evidenced a similarly emotional factor in his own personal anti-Christian commitment. Indeed, Russell openly appealed to emotional feelings of courage, pride, freedom and self-worth as a basis for his audience to refrain from being Christians!

Similarly, Russell tried to take Christians to task for their “wickedness” (as though there could be any such thing within Russell’s worldview)—for their cruelty, wars, inquisitions, etc. Russell did not pause for even a moment, however, to reflect on the far-surpassing cruelty and violence of non-Christians throughout history. Genghis Khan, Vlad the Impaler, Marquis de Sade and a whole cast of other butchers were not known in history for their Christian professions, after all! This is all conveniently swept under the carpet in Russell’s hypocritical disdain for the moral errors of the Christian church.

Russell’s essay “Why I Am Not a Christian” reveals to us that even the intellectually elite of this world are refuted by their own errors in opposing the truth of the Christian faith. There is no credibility to a challenge to Christianity which evidences prejudicial conjecture, logical fallacies, unargued philosophical bias, behavior which betrays professed beliefs, and presuppositions which do not comport with each other. Why wasn’t Russell a Christian? Given his weak effort at criticism, one would have to conclude that it was not for intellectual reasons.

Notes

1 The article is found in Bertrand Russell, Why I Am Not a Christian, And Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects, ed. Paul Edwards (New York: Simon and Schuster, Clarion, 1957), pp. 3-23.

2 Ibid., p. vi.

3 Ibid., pp. 115-16.

4 In his lecture Russell displays a curious and capricious shifting around for the standard which defines the content of “Christian” beliefs. Here he arbitrarily assumes that what the Roman magisterium says is the standard of Christian faith. Yet in the paragraph immediately preceding, Russell claimed that the doctrine of hell was not essential to Christian belief because the Privy Council of the English Parliament had so decreed (over the dissent of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York). Elsewhere Russell departs from this criterion of Christianity and excoriates the teaching of Jesus, based upon the Bible, that the unrepentant face everlasting damnation. Russell had no interest in being consistent or fair in dealing with Christianity as his opponent. When convenient he defined the faith according to the Bible, but when it was more convenient for his polemical purposes he shifted to defining the faith according to the English Parliament or the Roman Catholic church.

5 Those familiar with Russell’s detailed (and noteworthy, seminal) work in philosophy would point out that, despite his brilliance, Russell’s “unaided reason” could never resolve certain semantic and logical paradoxes which arise in his account of logic, mathematics and language. His most reverent followers concede that Russell’s theories are subject to criticism.