AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

Review of Herman Ausubel, Historians and Their Craft: A Study of the Presidential Addresses of the American Historical Association, 1884-1945. (“Studies in history, economics, and public law,” edited by the faculty of political science of Columbia University, No. 567.) New York: Columbia University Press, 1950. From The Journal of Modern History, 23:2, June 1951, 163-64.

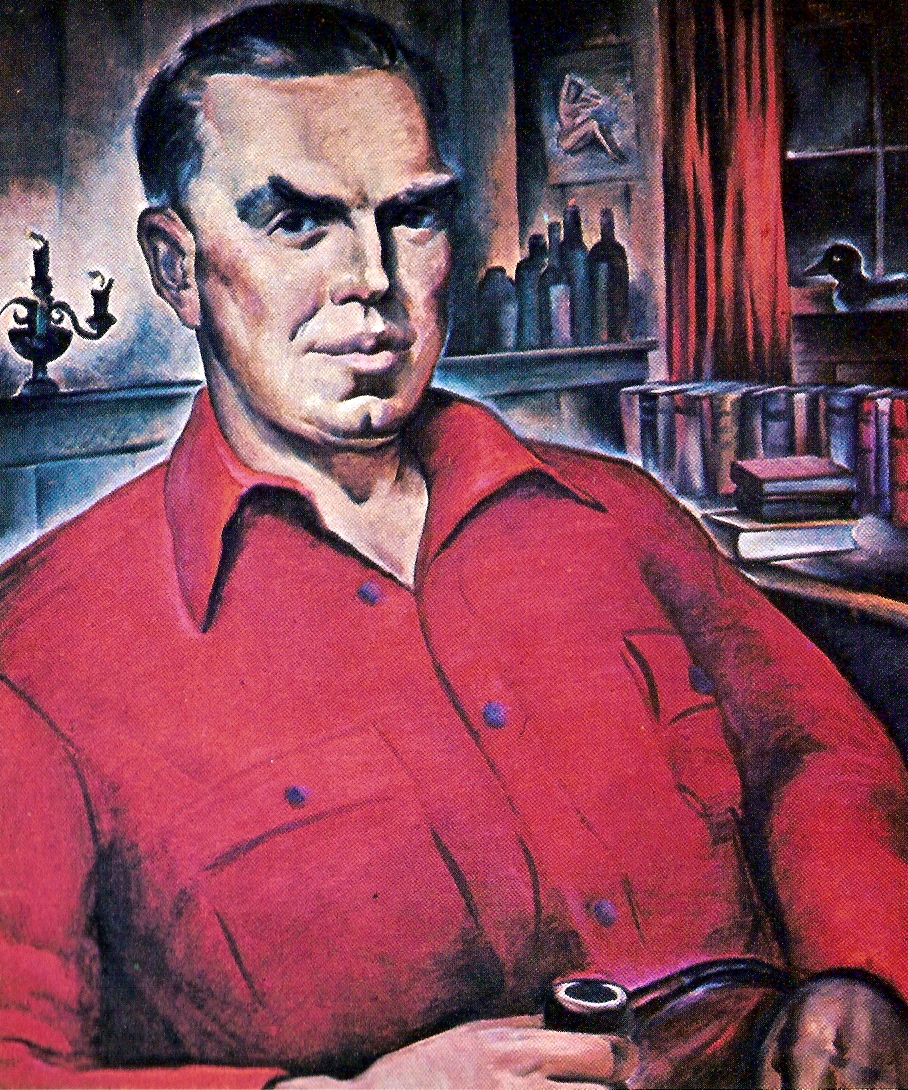

Harry Elmer Barnes

Herman Ausubel’s book may fairly be described as one of the most important contributions to historiography and the history of historical writing to appear in recent years. It will also serve to recall to the present generation of historians early scholars in the guild of whom they know little, even though these predecessors laid the groundwork for the craft in which the historians of today work and prosper. Incidentally, one of the past presidents, Captain Alfred T. Mahan, was probably the man most responsible for the public difficulties and social frustrations which beset our era, historians included.

The conceptions of history entertained by the successive presidents of the American Historical Association provide a fairly representative panorama of the development and diversities of historical thought in the United States, though it must be recognized that the presidents were not invariably the ablest and most scholarly practitioners in the field at the time of their elevation to the presidency. Just as an example, considerable explanation would be in order to account for the fact that William Roscoe Thayer was thus honored and Ferdinand Schevill was not or that William Milligan Sloane held an office denied to Herbert L. Osgood. Some of the presidents were obviously chosen because of their prestige in public life, others for their services in war propaganda, and still others for their astuteness and energy in association politics. As the reviewer happens to know personally, James Harvey Robinson was awarded the accolade only because of concentrated sub rosa activity on the part of appreciative former students.

On the whole, however, an exposition of the views of the presidents of the association gives us a better-than-average sampling of the evolution of historical scholarship and thinking in our country. Ausubel has performed the task in commendable fashion with respect both to research and to sound judgment. His book must be regarded as one of the best doctoral dissertations ever turned out at Columbia University. It is, thus, a tribute to the wise and scholarly judgment of Robert L. Schuyler, under whose direction the book was prepared and who has just been fitly honored by election to the presidency of the association.

Ausubel wisely does not give us a mere summary of the content of the presidential addresses in chronological order. Rather he divides his treatment topically, to include the more important problems of historical science and interpretation: (1) the utility of history in promoting social intelligence and providing public guidance; (2) history as literature; (3) the nature of historical facts; (4) the science and philosophy of history; (5) the role of individuals in history; and (6) the expanding conception of the desirable content of history. He then presents, chronologically, with many wise and often critical observations, the convictions of the past presidents in each of these leading phases of historical interest.

It is unfortunate that sometimes the most important and cogent statements by the presidents never got into print. Such is notably the case with Carl Becker’s famous paper “What is an historical fact?” delivered at the Rochester meeting of the association in 1926. This was probably the most important discussion of the nature of historical facts ever contributed by an American historian. For some unexplained reason, Becker failed to include it along with his other essays in his Everyman his own historian (Journal, VII [1935], 465). Occasionally, though rarely, important printed material has escaped Ausubel’s eye. Notable in this respect is the posthumous collection of Robinson’s essays, The human comedy (Journal, IX [1937], 367), which contains much the best presentation of Robinson’s views on the utility of history in promoting social intelligence.

To discuss and appraise in any detail the views of even one of the more thoughtful among the past presidents would require more space than is assigned to this entire review. Hence we may well close with the observation that Ausubel’s book is obligatory reading for every American historian of our day who has any deep interest in the evolution and content of historical writing in our country during the last sixty-five years.

Cooperstown, New York

Posted February 17, 2008