AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

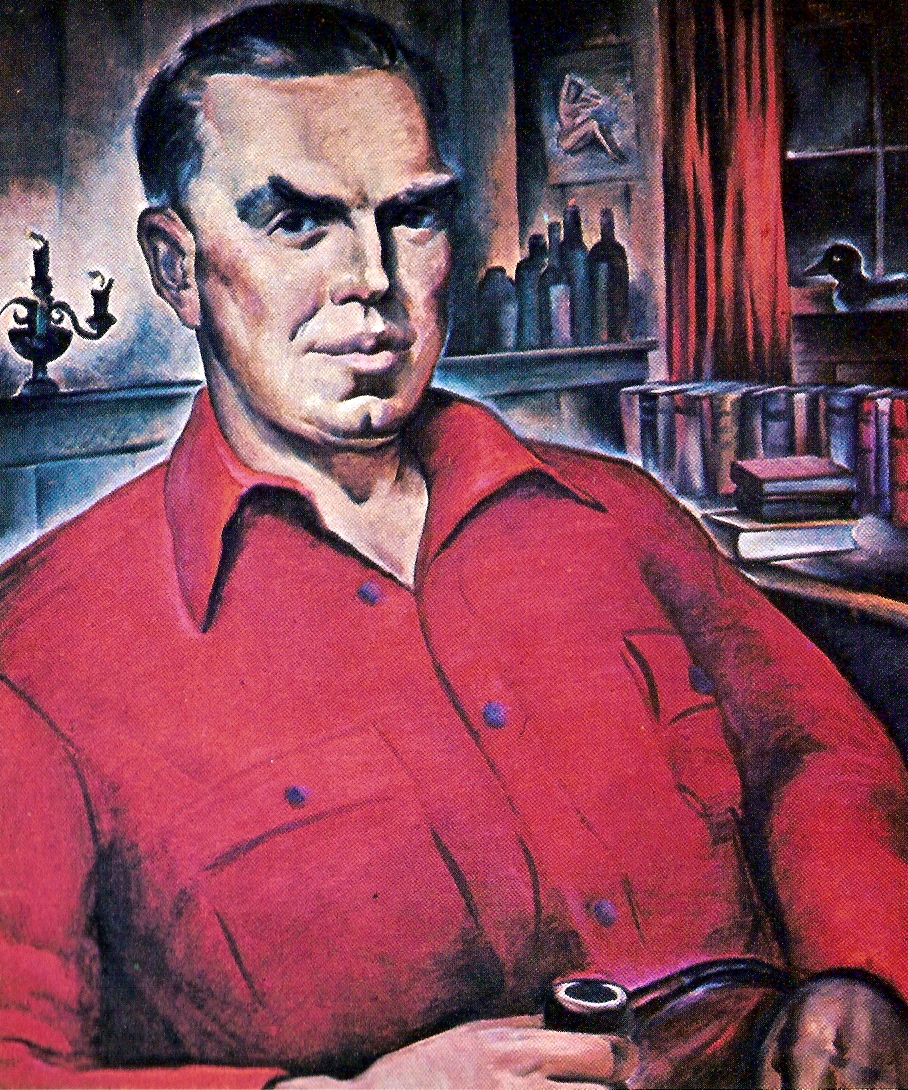

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Review of Charles A. Beard, The Nature of the Social Sciences in relation to Objectives of Instruction. [American Historical Association, Report of the Commission on the Social Studies, Part VII] New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1934. From The American Historical Review, 40:1, October 1934, 98-99.

Harry Elmer Barnes

Dr. Beard’s book is one of the basic volumes in the reports of the Commission on the Social Studies in the Schools, sponsored by the American Historical Association and executed under the direction of Professors A[ugust]. C[harles]. Krey and G[eorge]. S[ylvester]. Counts.

The recently published Conclusions and Recommendations of this commission aroused a great deal of controversy and attracted much public discussion. Of the work of the commission as a whole it may safely be said that it is one of the major landmarks in the history of American education as well as in the history of the social sciences in this country. It may well prove equally significant and potent in the reconstruction of American society if this is ever accomplished by rational methods and according to scientific principles.

Professor Beard has already written a brief volume for the commission entitled A Charter for the Social Sciences, a general introduction to the field of the social sciences and a vindication of the need for the kind of work which the commission has undertaken. The present volume is a more extensive and difficult work which treats of the problems of the social sciences as a whole, the nature of each of the leading social sciences, and the objectives to be sought for in improving the character of the social sciences and in making their content ever more useful for the guidance of human society. The book is one of the most thoughtful and constructive works ever published in the history of American social theory and pedagogical perspectives.

In his long introductory chapter on the nature of the social sciences Professor Beard comes to grips with the fundamental problem of whether the social sciences can ever attain to the exactness, precision, and objectivity of the mathematical and natural sciences. He frankly agrees that they cannot: “There is and can be no science of society or partial science of society, such as politics or economics, in any genuine sense of the term. No science, natural or social, really explains anything, if the term is employed with respect to exactness of thinking.” Yet the social sciences can presume to provide us with a very accurate description of social data and social processes and can formulate at least tentative laws of social behavior:

“The social sciences cannot supply a complete body of deterministic laws covering all the relevant data of politics, economics, and sociology. They can, however, with the aid of the empirical method, disclose certain areas of human behavior in which repetitions of conduct and responses to stimuli seem so regular, for a short period of time, as to justify the application of the term ‘laws’ to them. For example, economists, as a result of historical inquiries, can predict within certain broad limits, what will happen to prices and wages, if the currency of a given country is extremely inflated.” Moreover, whether strictly scientific or not, the social sciences bring forth a body of indispensable knowledge without which “modern civilization would sink down into primitive barbarism.”

This introductory appraisal of the general field of social science and of the limitations imposed upon it by the nature of its materials is followed by a very thoughtful analysis of the character and problems of history, political science, economics, and cultural sociology. To this is appended a discussion of contemporary social trends in the United States, based in part upon Professor Beard’s own wide observations and in part on the findings of the President’s Committee on Recent Social Trends. As one familiar with Dr. Beard’s professional interests and attitudes would expect, the chapters on history and political science are the most satisfactory and that on cultural sociology the least adequate.

Perhaps the most valuable and gratifying conclusion drawn from the author’s analysis of the several social sciences is a crushing assault on the particularists who would jealously divide the social sciences into air-tight compartments. Dr. Beard defends with spirit and determination the thesis that any such thing as a separate or special social science is a figment of the imagination or the illusion of a partisan. The field of social science is a unified one and specialization can be justified only on the ground of promoting greater precision and convenience. A general acceptance of this point of view would do much to promote good will and intelligent cooperation among those at work in the social sciences. Accepting for purely pragmatic and pedagogical purposes the conventional divisions of social science, Dr. Beard suggests that they be arranged in the following order from considerations of logical sequence and pedagogical effectiveness: Geography, Economics, Cultural Sociology, Political Science, and History.

The author deals very sensibly with the bitterly controversial question of how far the social sciences should go in recommending social reform and in guiding the task of increasing the well-being of mankind. He recognizes that the ethical or normative aspect of social science, namely, its contribution to the guidance of social reform, is the one practical justification of the empirical or more rigorously scientific phase of social science. But he also concedes that just to the degree that we pass over from the empirical into the ethical realm of social science we depart from strictly scientific controls.

The book as a whole conforms to the somewhat discrepant and paradoxical trend observable in Dr. Beard’s recent writings. On the one hand, he is eminently practical and shows a wide acquaintance with the literature of contemporary social description and analysis. On the other hand, in his theoretical observations he espouses that extreme abstraction of which he was himself at one time perhaps the foremost American critic. In the place of recognition of the work of [Karl Gottfried] Lamprecht, [Henri] Berr, [Walter T.] Marvin, [James Harvey] Robinson, [James T.] Shotwell, [Frederick Jackson] Turner, [Carl L.] Becker, and the like, we have reverent reference to the neo-Hegelian [Benedetto] Croce, [Karl] Heussi, [Kurt] Riezler, and [Max] Scheler. Even Hegel, who was once veritably Dr. Beard’s personal devil, is mentioned with affection.

It may also be observed that in this, as well as in the other volumes thus far published by the commission, there is a regrettable and ungenerous ignoring of the scholars who really put the social science movement on its feet in the United States and created the interest in the field which made possible the origins and work of the present commission.

In any event, this volume and the work of the commission as a whole constitute a most impressive demonstration of the progress in liberality and tolerance on the part of American social scientists during the last thirty years. In New Orleans in 1903 there was a joint meeting of the American Sociological, Economic, and Historical associations at which Professor Franklin H. Giddings presented what he regarded as a common point of departure for the social sciences in the form of a highly generalized “Theory of Social Causation.” Open, and in some cases bitter, hostility was evidenced toward this position by the economists and historians who commented on Professor Giddings’s paper. This was particularly true of the historians. Thirty years later we find the American Historical Association sponsoring a position toward social science quite as synthetic, daring, and far-reaching in its implications as those set forth by Professor Giddings. There is every reason to think that the next thirty years will be even more productive of tolerance, urbanity, and constructive achievements in the realm of social science.

New School for Social Research

Posted February 17, 2008