AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

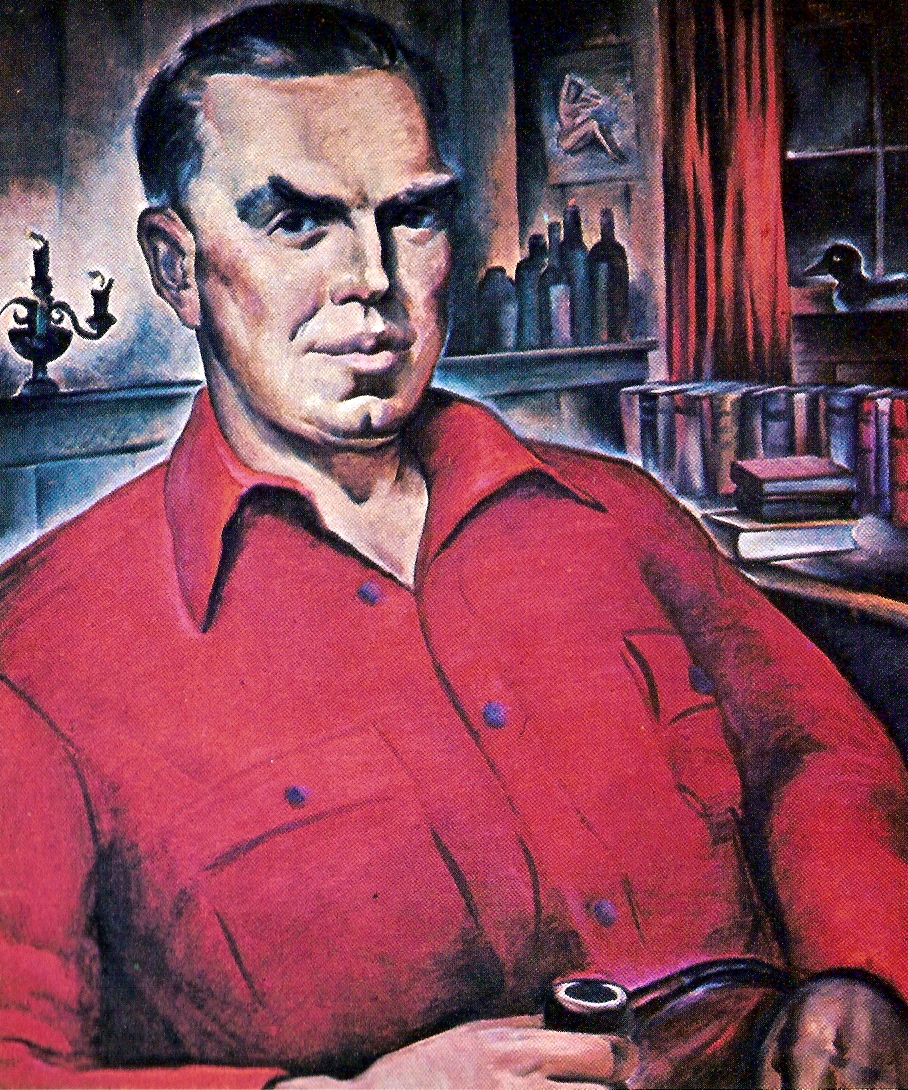

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Review of Christopher Dawson, The Dynamics of World History, John J. Mulloy ed. New York: Sheed and Ward 1956. From The American Historical Review, 63:1, October 1957, 77-79.

Harry Elmer Barnes

Christopher Dawson is, perhaps, the most thoughtful, stimulating, and suggestive historian of the Catholic faith who in this century has devoted himself to the general history of civilization. He is more down to earth and convincing than [Oswald] Spengler or [Arnold J.] Toynbee. He is also more modest, for he tells us that “the history of a single civilization seems to be the most that we can hope to achieve.” Those historians who have known of Dawson only through his brilliant volume on The Making of Europe will be surprised, whether pleasantly or not, when they read the book under review. It reveals Dawson as a writer so well versed in anthropology, sociology, psychology, and the basic ideas which have dominated historical perspectives over the ages that he almost measures up to the pattern of the ideal historian recommended by James Harvey Robinson in his The New History.

The Dynamics of World History is an anthology—not an abridgement—of Dawson's writings on the history of civilization, selected by a learned and discriminating admirer, John J. Mulloy, who adds a supplement of more than fifty pages summarizing and interpreting Dawson's ideas. Mulloy seems determined that no reader miss, distort, or undervalue any of Dawson's achievements or convictions. The volume contains more articles, lectures, and essays than excerpts from his chief books, although there are some of the latter. It therefore not only gives a new and less well-known impression of Dawson as a historian but also presents material which will be fresh to all save those who have been close followers of his writings in the past.

In his approach to the history of civilization, Dawson adopts what he calls a sociological frame of reference. The fields and issues which most concern him are the relations between primitive and so-called historic cultures, the contact of cultures and the resulting cross-fertilization, the dynamic or causative factors in the development of human culture, the main theories of cultural evolution and world history presented during the Christian era, and comparative religion, with special emphasis on the influence of religion on the course of human development and its interpretations.

The book has two main parts: a broad sociological approach to the chief factors, stages, and problems in the history of civilization, stressing the importance of urban civilization in our day, which reflects the influence of Patrick Geddes and Victor Branford; and a discussion of the great conceptions or panoramas of world history set forth from Augustine's City of God to Toynbee's A Study of History. Dawson's appraisal of these interpretations of the nature and meaning of world history is astute, judicious, and informing. He attributes emergence of the conception of world history, with an impressive future lying ahead, to the influence of Judaism and Christianity, which, he claims, really launched the sociological approach to history. The philosophical interpretation of history by the classical thinkers and historians produced a provincial and restricted outlook on human development and a belief in recurring cycles rather than a dynamic conception of progress.

Perfectionists will find some things to complain about. They may hold that, although Dawson assumes to adopt a sociological interpretation of history, theology takes over in the ultimate showdown; that his conception of sociology is rather archaic and also highly selective, in that he chooses particular sociologists and even those views which clash the least with Catholic dogma; and that, although he criticizes the philosophical approach to history, he really approves it in his theory of “metahistory.” Nevertheless, not even the most militant Protestant or skeptical historian, if he is fair and honest, can read this book without being impressed by Dawson’s learning, comprehension, and perspective or stimulated by his remarkable ability to go to the heart of an issue, to state his points and conclusions with great cogency and brilliant precision. Those who differ with him about basic ideology will profit by seeking to observe or emulate the same degree of mellowness, urbanity, and tolerance which permeates Dawson's writings.

In the concluding chapter, Dawson makes clear that the long era during which Europe has dominated the course of human civilization has now come to an end, and he draws some sagacious conclusions as to the import of this for the human future. This is a book which no thoughtful historian can safely ignore, and it is as timely as it is illuminating.

Malibu, California

Posted February 17, 2008