AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

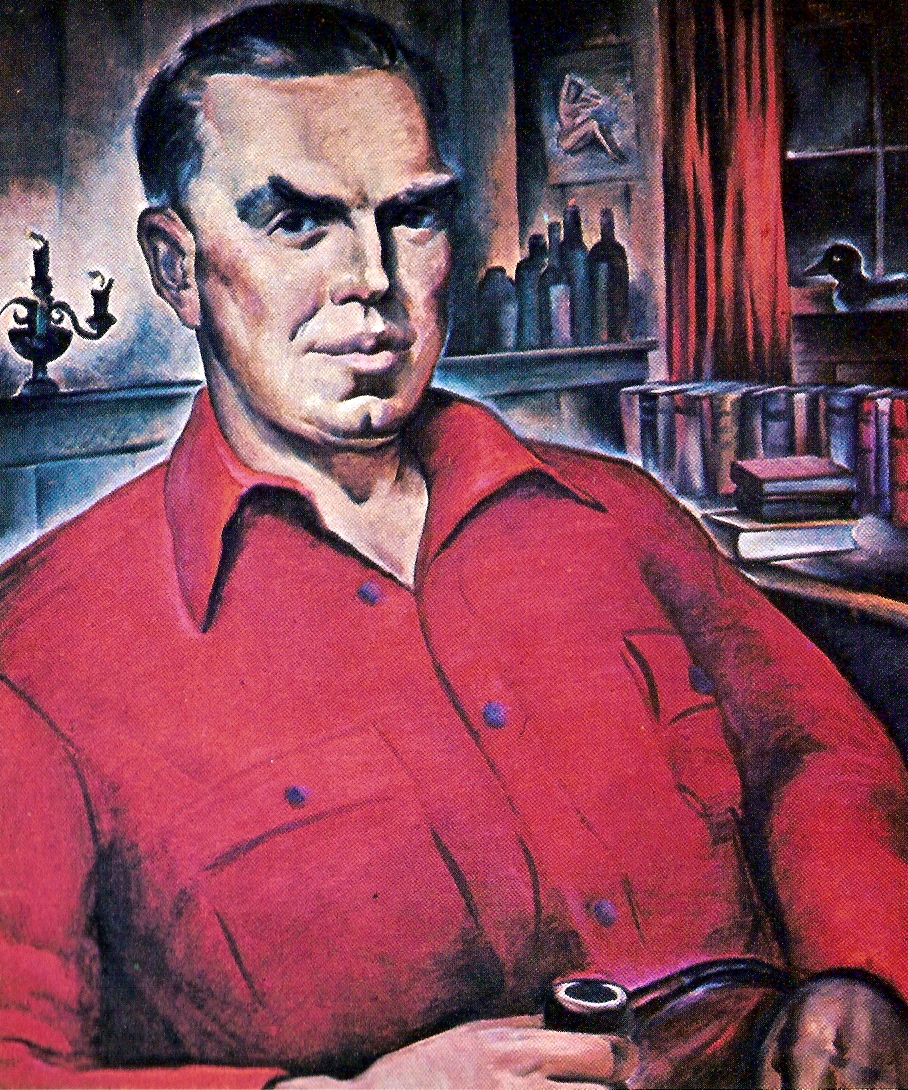

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

From The American Historical Review, 35:1, October 1929, 76-78.

The German Declaration of War on France: The Question of Telegram Mutilations

Premier Poincaré versus Ambassador von Schoen

Harry Elmer Barnes

One of the problems related to the outbreak of the World War which is still warmly debated and as yet unsettled is that connected with the telegrams sent by the German government to the German ambassador in Paris directing the latter to hand a declaration of war to the French government. Baron von Schoen has always contended that portions of these telegrams were mutilated so that he could not determine their contents before he left Paris. The French have denied this and have maintained that there was no mutilation of these telegrams. In his Memoirs (English edition, II, 287) M. [Raymond] Poincaré has, within the last year, repeated his charge against Baron von Schoen under the heading: “Another German Fable.” We reproduce this section in full:

Whatever falsehoods besides occurred in the Note which Baron Schoen handed to [René] Viviani, others lurked in the text sent from Berlin. The German Government had notified their Ambassador, not only as to the alleged flights, but of military raids on terra firma through Montreux-Vieux and by a path through the Vosges, and at the very moment when the telegram was being penned to Schoen, Herr Jagow seriously affirmed that French troops were still on German soil. Why on earth did not the Ambassador [Schoen] make use of this information in his letter? Did he suspect its fantastic character? He has explained in his Memoirs that the telegram was so illegible that it could not be entirely deciphered, and this explanation has given rise to many suppositions. M. [François Victor Alphonse] Aulard has gone closely into the question of the telegram being undecipherable, and says the thing is highly improbable; anyhow, at the time the Quai d'Orsay had no key to the German cipher, which was only found and applied to the Schoen telegram much later in the war. It was therefore quite impossible for our people at the Foreign Office to read a telegram before sending it on. Since the war, a German Commission has gone all through the archives of the General Staff, and nothing so far has turned up to give the slightest indication of any concerted French reconnaissance in Alsace—even on the 3rd of August—or of any action which can be compared with the German cavalry raids through Belfort and Lorraine.

In order to get further light on this subject I called the attention of Baron von Schoen to Poincaré’s statement and asked him to furnish me with a full statement of his version of the case. Baron von Schoen sent me a reply on November 16, 1928. This, in full, is as follows:

As is well known, the German declaration of war on France on August 3, 1914, did not read as it should have read, because the cipher-code telegram containing the order to the German ambassador in Paris arrived garbled to such an extent that only portions were readable. Because of this unfortunate circumstance, the explanation forwarded by the ambassador to the French government could only be based on the French air-attacks, but not on the much more significant war-manoeuvres of the French troops. Soon, from the German side, an explanation of this affair and the correct wording of the distorted telegram was officially made known. Also, as soon as the truth was established, it was admitted that the reports of air-attacks were attributable to errors. In spite of that, the French statesmen, during the war and long afterward, stubbornly hurled the reproach at Germany that it had attacked France treacherously, under false pretenses. Not until several years after the conclusion of peace, when Ambassador Baron von Schoen publicly appealed to the sense of honor of the former President, Poincaré, did the latter moderate his accusations and admit that, in regard to the German assertion of air-attacks, a mistake, not a conscious falsehood, may have been involved. He started on another wrong track, however, with the assertion of doubt whether there really had been despatch-mutilations, and hinted that these might have been put up as a defense by the German ambassador. In the fourth volume of his Memoirs,1 he touches upon the matter again and refers to an article by the French historian Aulard, in the Revue de Paris of May 1, 1922, in which this scholar endeavors to prove this dispatch-mutilations a poorly founded myth, or even Schoen's own work. But Mr. Poincaré overlooks the fact completely that Baron Schoen in the German magazine, Die Nation, of July, 1922, had curtly denied these scurrilous assumptions and inferences and had characterized them as proofs not only of short-sighted, but of malicious, prejudice.

How Mr. Poincare, who also allows himself to be led here and there into an explanation of the happenings which differs from that given by Schoen in his Memoirs, can make these contradictions agree with his oft-expressed recognition of the unimpeachable integrity of the former German ambassador, is a puzzle, just as it is an unsolved question how and where the mysterious despatch-mutilation originated. An unfortunate circumstance? Disturbances of relations? It may be. But set over against this hypothesis there is a very remarkable circumstance, namely, the fact that not only one Berlin despatch concerning the declaration of war of August 3, 1914, was mutilated, and therefore came into the hands of the ambassador only partly readable, but rather two of them: (1) the one sent in the morning from Berlin and signed by State-Secretary von Jagow; and (2) the other sent in the afternoon, personally signed by the Imperial Chancellor.2 Moreover, a strange coincidence: in both telegrams the very same portions of the text, namely, those that concerned the frontier violation by the French troops, were made unreadable by the transposition of the code-ciphers, and in fact by unmistakably systematic falsification. Moreover, it is striking that the two German telegrams were over five hours on the way, but a telegram of the French ambassador in Berlin, sent almost at the same time as the second one, was only three hours on the way. And this telegram was not garbled.

One more point! Professor Aulard mentions in regard to the first German telegram, that of Jagow, that a rectifying repetition requested by Schoen had arrived in Paris long after the departure of the ambassador, and that this repetition had shown no falsification whatsoever. This allows us to conclude that in Paris, outside of the German Embassy, they were in a position to decipher this telegram and compare it with the original. Mr. Poincaré, on the other hand, assures us that the French office at that time was not in possession of the key to the German cipher-code—again a riddle!

1 L’Union Sacrée, p. 525 (English edition, II. 287).

2 German Documents, nos. 716, 734.

Posted February 17, 2008