AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

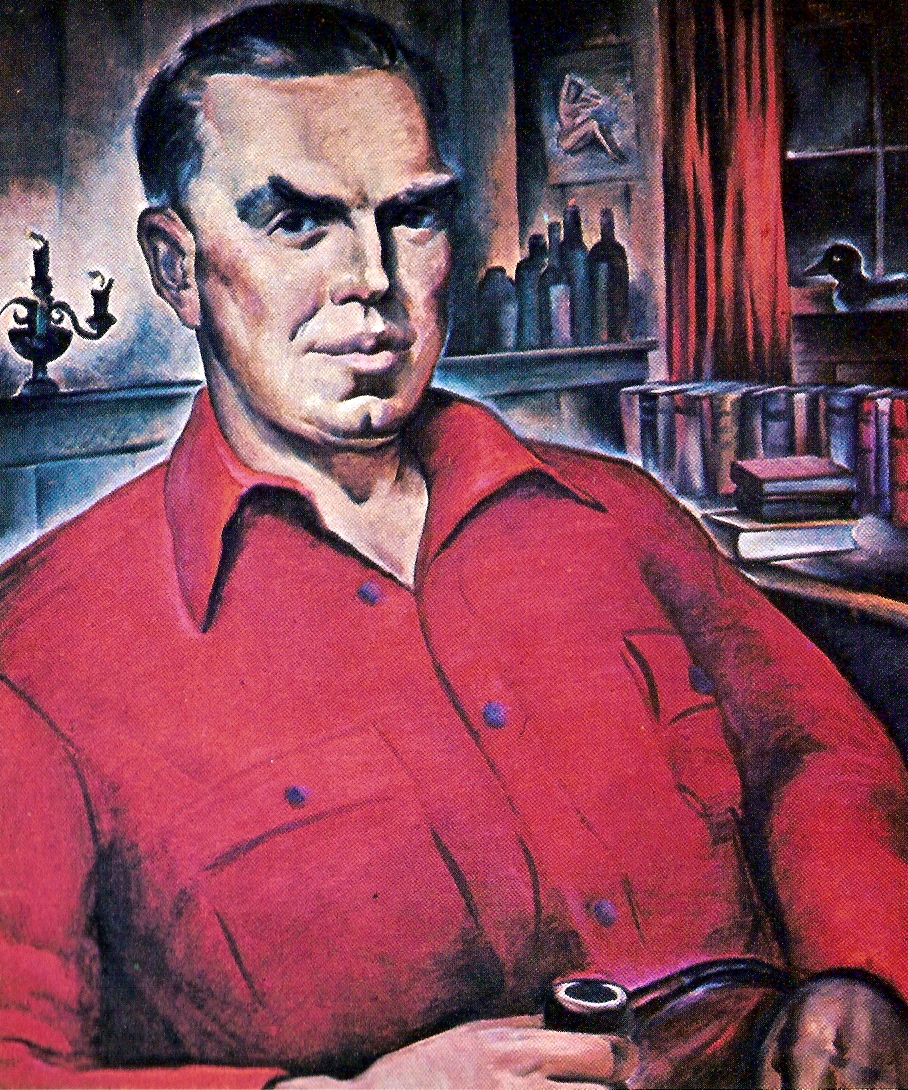

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Review of Alexander A. Goldenweiser, Early Civilization: An Introduction to Anthropology, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1922. From The American Historical Review, 28:2, January 1923, 293-94.

Harry Elmer Barnes

The significance of anthropology for the historian has only recently been extensively recognized. Professor Robinson quotes Salomon Reinach as the authority for the statement that [Theodor] Mommsen had never heard of the ice age until shortly before his death. At the present time the situation has been greatly altered. Eduard Meyer introduces his latest edition of the Geschichte des Altertums by a whole volume on anthropology, and Professor [James Henry] Breasted’s recent works give evidence of a thorough mastery of the so-called “prehistoric” period. Further, historians who have concerned themselves with the history of civilization have derived much aid from anthropology in the matter of the laws and processes of cultural development. Illustrations of this influence are to be found in such works as those by [Karl Gottfried] Lamprecht and [Kurt] Breysig, and the theoretical bearings of the problem have been admirably discussed by Professor [Frederick J.] Teggart in his two interesting volumes, Prolegomena to History, and The Processes of History. Finally, it was, perhaps, the chief contribution of Mr. [H. G.] Wells to bring to the general public a conception of the importance of anthropology as the background for history.

Until the publication of Dr. Goldenweiser’s work historians have been at somewhat of a disadvantage in the attempt to utilize the results of anthropological research. With the exception of the charming little volume by Professor [Robert Ranulph] Marett, the only available synthesis of anthropology was the remarkable manual of Sir E[dward]. B[urnett]. Tylor, first published in 1881 and never seriously revised. Since that time, owing chiefly to the work of Professor [Franz] Boas and his students, the methods and results of anthropology have been revolutionized, and the limitations and errors of the older type of work by [Baron] Avebury [John Lubbock], [James] Frazer, [Lewis H.] Morgan, and [Charles] Letourneau fully revealed. The results of certain aspects of this newer variety of anthropological investigation have been set forth in works by Boas, [Robert] Lowie, [Clark David] Wissler, and others, but the volume by Dr. Goldenweiser is the first important effort to synthesize the assured achievements of the research of the present generation of critical anthropologists.

The work opens with a consideration of certain basic methodological premises and concepts of theoretical anthropology. Then come several interesting chapters giving a concrete description of a number of typical primitive communities widely distributed in location. In part II, the industrial life, art, religion, and social organization of primitive men are admirably described and critically analyzed. This is unquestionably the most valuable and significant portion of the book. In the concluding chapters the author contrasts the earlier views of the mental traits of primitive men held by [Baldwin] Spencer, Frazer, and [Wilhelm] Wundt with certain newer interpretations by [Émile] Durkheim, [Lucien] Lévy-Brühl, and [Sigmund] Freud. It is, perhaps, regrettable that, as the expositor of the psycho-analytic point of view, W[illiam]. H[alse]. R[ivers]. Rivers was not chosen in the place of Freud.

Throughout the work the basic assumption is that cultural phenomena are the raw material of anthropological and historical study. Racialists following [Arthur de] Gobineau and biological extremists, geographical determinists of the [Friedrich] Ratzel school, and adherents to the psychological interpretation of history, such as the followers of Wundt and Lamprecht, will derive scant comfort from these pages. Yet Dr. Goldenweiser utilizes this “culture-concept” of the Boas school with moderation. Likewise, in considering the various theories of cultural development, he gives proper weight to all of the leading hypotheses. In every phase of analysis most of the significant recent interpretations are fairly but critically presented, and the work is thoroughly up to date in every respect. While by no means as brilliantly written as the previous works of Tylor and Marett, the book is well arranged and the diction clear. To those historians who are interested in the development of civilization or in the laws and processes of cultural and social evolution Dr. Goldenweiser’s work will prove a timely and indispensable aid.

Posted February 17, 2008