AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

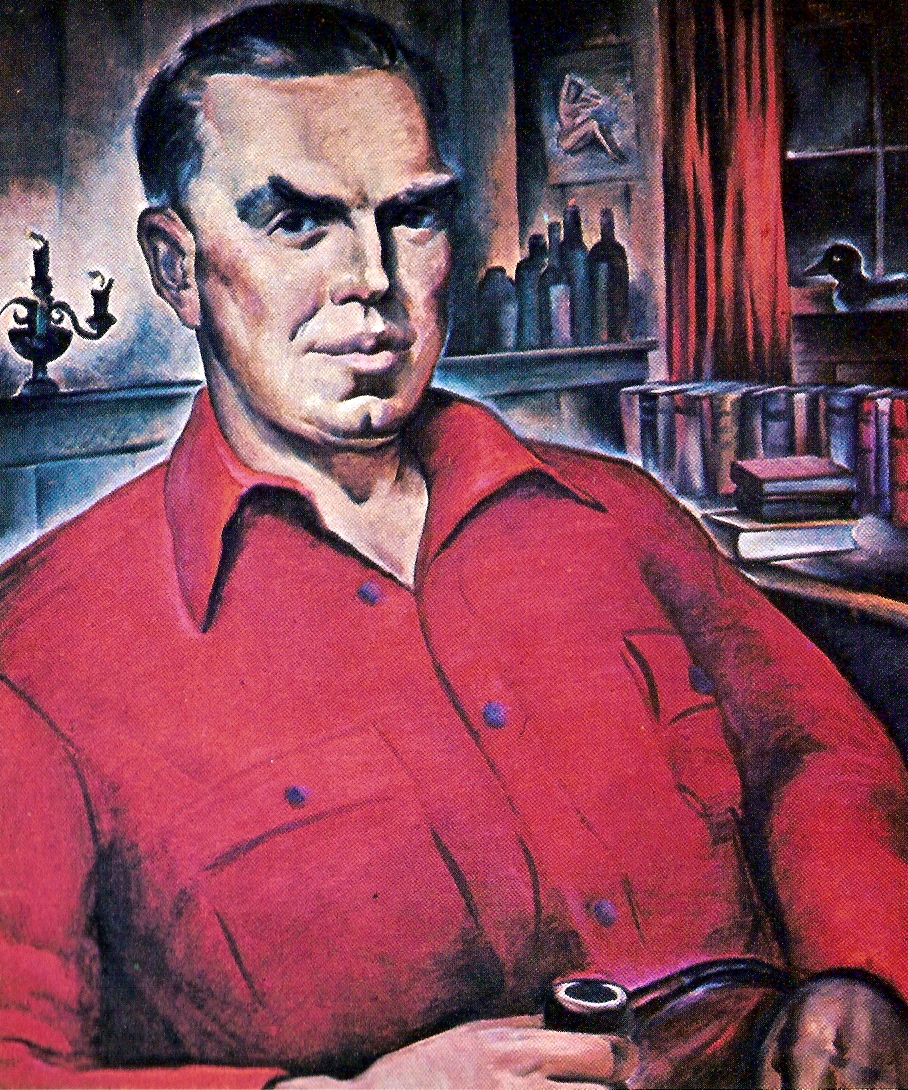

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

From Whose Togas I Dangle

A Gallery of Heroes

The Public Stake In Revisionism

Harry Elmer Barnes

Every American citizen has much more at stake in understanding how and why the U.S. was drawn into World War II than in perusing the Warren Report, its supplementary volumes, and the controversial articles and books of the aftermath, or the annals of any isolated public crime, however dramatic.

However tragic and regrettable, the assassination of President Kennedy was a relatively simple crime as compared to perhaps the most lethal and complicated public crime of modern times, our entry into World War II. This resulted in the immediate loss of over thirty million lives, an ultimate cost of more than fifteen trillion dollars, incredible suffering, and a military-scientific-technological-industrial aftermath which may wipe out the human race; and the concomitant result: a conditioned outlook whereby millions favor war—exerted externally upon a foreign "enemy" and internally upon the taxpayers—as the means to insure peace.

Do we need more books to vindicate revisionism?

Although a formidable array of evidence has been amassed and offered by Revisionist scholars as to our involvement in World War II, this evidence has not been fully recognized or generally understood. Writing in 1965, Richard J. Whalen. author of the brilliant The Founding Father, stated:[1]

In the twentieth year after the end of World War II, we still do not have an unsparingly truthful, solidly authoritative account of how and why the United States was drawn into World War II. And it is becoming doubtful that we will ever have it.

The reasons are many: World War II was the liberals' war and they are understandably determined to uphold their version of its origins with all the formidable political and intellectual resources at their command. There is also our necessary preoccupation with the successor struggle now centered on Southeast Asia; with so much to comprehend here and now, a searching look backward at our tragic line of march seems almost a luxury we can ill afford. But most important of all. we are losing our hope of the truth about the central experience of our time simply because time is passing.

Research is a young man's occupation, particularly the kind of relentless inquiry required to uncover and piece together information that powerful vested interests wish to conceal. Unfortunately, those under forty who are researching and writing history for the next generation with rare exceptions have accepted the "explanation" of World War II provided by folklore and orthodox scholarship. The dissenters—the Revisionist historians—have not been able to reach the generation that has come of age since the war; the latter are scarcely aware that another side of the story exists.

Twenty years after Versailles, the situation was entirely different. The tidal wave of disillusionment that swept through the West brought a flood of scholarly and popular books debunking the official history of the war. Revisionism became an integral part of the dominant liberalism of the period. But the younger journalists and historians who revolted against their elders following the first World War have, in the years since the last war, succeeded brilliantly in forestalling a like revolt against themselves. And so we have missed the debunking generation, and the question is whether we can somehow stimulate a ferocious curiosity in the next. The odds are heavily against it . . . .

The Revisionists . . . must exert themselves to produce truly arresting and provocative studies within a framework geared to a new era and a new audience, works that will thrust deep into the public consciousness and at last wrench open a prematurely closed subject of paramount importance.

While agreeing, in general, with Mr. Whalen's informed and judicious appraisal of the Revisionist situation, I would bluntly, if amiably, question his assertion that in two decades after V-J Day "we still do not have an unsparingly truthful, solidly authoritative account of how and why the United States was drawn into World War II," unless he demands absolute perfection, which was not attained by any Revisionist book written after World War I. Since I am probably more familiar than any other person, living or dead, with the Revisionist literature on the causes of both world wars and our entry into them, I would say that we have actually been especially fortunate in the number and quality of the Revisionist books which have appeared on this subject since V-J Day—more and better books than were published on our entry into the first World War in the same period of time. Although we should always welcome new and possibly better books on the subject, we have no more pressing need of another comprehensive and readable book on the causes of American entry into the second World War than we have of another good biography of Joseph P. Kennedy, now that Mr. Whalen has supplied us with an absorbing and masterly treatment of this subject.

By 1948, we had Charles Austin Beard's two magisterial volumes on the causes of our entry into the war, carrying the story right down into Pearl Harbor and the comprehensive book by George Morgenstern on Pearl Harbor, which is surely the outstanding tour de force in the Revisionist literature of either world war and has not been discredited on any essential matters, despite the extensively subsidized, widely publicized, and lavishly praised efforts of Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison and Roberta Wohlstetter.

By 1950, we had William H. Chamberlin's America's Second Crusade, which matched for reliable information and brilliance of style Walter Millis' widely read Road to War that told the same story relative to our first crusade. In 1951, Frederic R. Sanborn's very able and scholarly book, Design for War, was published, but it was destined to become the most unfortunately ignored Revisionist book on our entry into the second World War, despite its impressive scholarship, its lucid style, and the distinction of the author. It did not get even a book note in the American Historical Review.

By 1953, we had two additional books which qualified even more impressively for supplying the lacuna regretted by Mr. Whalen, Charles Callan Tansill's Back Door to War (1952), and the book I edited on Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace (1953).

Tansill's America Goes to War (1938) was the first exhaustively scholarly work on how we were drawn into the first World War, and this did not appear until two decades after the Armistice of 1918. It was praised in the Yale Review of June 1938, in the following lyrical fashion by no less than Professor Henry Steele Commager, a participant in the historical blackout on World War II Revisionism: "It is critical, searching, and judicious...a style that is always vigorous and sometimes brilliant. It is the most valuable contribution to the history of the prewar years in our literature, and one of the most notable achievements of historical scholarship of this generation."

In my opinion, Back Door to War is equally brilliant and reliable, and is an even more useful book in that it also provides an account of the causes of the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 almost as comprehensive as A. J. P. Taylor's Origins of the Second World War, and based on more thorough documentation. That the latter book brought so much consternation to American readers nearly a decade later, only underlines the manner in which Tansill's invaluable labors had been missed by the literate American public and brushed aside by the rank and file of professional historians.

The difference in the reception of Tansill's two books was almost entirely due to the change in the climate of historical and public opinion, an impressive example of historical "relativism." America Goes to War appeared at the moment of the maximum triumph of Revisionist literature on World War I; Back Door came out when the blackout against World War II Revisionism was already getting organized and solidified. The fact that Back Door had a relatively large sale for a book of its nature was due in part to an intensive and expensive promotional campaign but perhaps even more to the fact that historians and publicists had not fully realized the actual nature, force, and implications of World War II Revisionism until they had read the Tansill volume. Thereupon, they rallied to the colors that had been hoisted and waved by Admiral Morison and lesser lights in the historical profession, the historical blackout was intensified and congealed, and it has never let up since. Further academic use of Back Door was discouraged, and a considerable portion of a later edition was sold at remainder prices.

A book that probably qualified even more perfectly for filling the gap mentioned by Mr. Whalen was Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace. It is doubtful if there will ever be a better work written for this purpose. Subsequent research in this field gives no indication that any fundamental changes will be needed in the essential phases of the narrative, and the minor ones required will be more than offset by the reduced familiarity of future authors with the times, of which the authors of Perpetual War were highly intelligent, informed, and favored witnesses. Moreover, it combined and exploited the knowledge and ability of the leading American Revisionists of that day save for Beard, who had already passed away. The book was extremely well written throughout and rather more readable than most books of its nature and intent. Yet, despite vigorous promotional efforts, the book was a pathetic publishing flop. Not more than half of the modest first printing was sold, and the remainder were purchased by one of the richest Americans for fifty cents a copy to distribute to grass-roots fundamentalists!

Instructive of an increasingly popular trend in reviewing by anti-Revisionists, namely, the tendency to evade the facts well established by Revisionist writers, was the review of the book by Bernard C. Cohen of Princeton University in the American Political Science Review, December, 1954. Cohen led off his review with the statement: "This is an unpleasant book to read." This set the tone of the whole review, which failed to come to grips with the facts presented in the book.

The content and challenge of the Tansill book had pulled the blackout contingent together into speedy action by the time that Perpetual War reached the market, and by 1954 it was obvious that a book or even more books were not the main answer to public enlightenment on the causes and results of our entry into the second World War. A number of other good books have appeared since that time, but this is not the place to provide a bibliography of World War II Revisionism. [2]

The essence of the matter is that the historical profession has rallied and fully exploited the suggestion of Samuel Flagg Bemis in 1947 that books like Morgenstern's, which place guilt on President Roosevelt, are "serious, unfortunate, deplorable." [3] Writing in the top collaborative American History series, "the New American Nation," edited by Commager and Richard B. Morris, Professor Foster Rhea Dulles could state that "there is no evidence whatsoever to support such charges," as those advanced by Beard, Morgenstern, Tansill, Admiral Theobald, et al, relative to Roosevelt's responsibility for the Pearl Harbor surprise, and Professor A. Russell Buchanan could write a two-volume history of the United States and the second World War in the same series as though there had been no World War II Revisionism.

There is no space here to recount the nature and operation of this historical blackout relative to World War II Revisionism. I dealt with this comprehensive and effective operation and the fate of most of the important Revisionist books down to 1953 in the first chapter of Perpetual War, and have since brought the story down to date in many articles, brochures, and reviews.[4]

The public is insulated from even readable revisionist books

The Revisionist books by Beard and Morgenstern were "loners" with which I had nothing to do except to welcome and commend them, and I first saw the Sanborn book in proofs and could do not more than to approve its publication and do what I could do to assist in its promotion, which was lamentably unsuccessful, despite the sound scholarship and great merit of the book.

The first book I arranged for was that of Mr. Chamberlin and it was designed to perform precisely the function that Mr. Whalen so eloquently pleads for in his final sentence. The author lived up very satisfactorily to our expectations. It would be difficult to envisage a book better designed to reach the literate public and induce them to reconsider the propaganda that led us into and through the second World War. If any book could "thrust deep into the public consciousness and wrench open a prematurely closed subject of paramount importance," America's Second Crusade should have done so, but even at this early date (1950) the blackout, stemming from wartime propaganda, was too rigid and well organized to permit this much-needed service.

Chamberlin's sound, reliable, and very readable volume sold less than ten thousand copies despite vigorous promotion, and six months after it appeared the publisher discovered that there was not a copy in the New York Public Library or in any of its forty-five branches. It was ignored by most of the important periodicals, was smeared by most of the newspapers that reviewed it, and historians, students and faculty alike, were protected from it by the fact that it did not even rate a book note, to say nothing of a review, in the American Historical Review. It was quite apparent that the times were not ready for a book like Millis' best-selling Road to War on our entry into the first World War, and the American public is far less attuned to one now than fifteen years ago. Mr. Regnery has reissued the Chamberlin book in an unusually attractive and economical paperback, but there is no evidence after several years that it has pressed Candy, Fanny Hill, or The Boston Strangler in reader demand.

The experience with several other brief and highly readable books further confirmed the difficulty of gaining any marked public response to Revisionist literature, even with the aid of unusual publicity. A basic Revisionist book, Popular Diplomacy and War, by Sisley Huddleston, a world-famous journalist and publicist, one of the best writers of the era, and long popular with American liberal journals, had the benefit of two very adulatory lead editorials in issues of the Saturday Evening Post, 18 December 1964, and 8 January 1965, potentially calling the book to the attention of more than ten million readers, counting subscribers, newsstand purchasers, and their families and friends. The publisher of the Huddleston book told me that he could not attribute a sale of more than a hundred copies specifically to these supposedly awesome editorials.

Writing revisionist books for the record

The question therefore inevitably arose as to sensible procedure in planning further Revisionist books. It was evident that little general excitement could be stirred by them, even when clearly and brilliantly written, although there was greater need for such public concern with Revisionist material than back in the days of my Genesis of the World War (1926) and Hartley Grattan's Why We Fought (1930). If we could not interest, to say nothing of arousing and exciting the public, we could at least write for the historical record, in the hope that Clio might ultimately escape from the embraces of what Captain Russell Grenfell has so colorfully called "the historical Gadarenes." It may be admitted that this writing for the record is a long shot, and that there is much to be said for Mr. Whalen's assertion that time may not be on the side of Revisionism. Yet, it is certain that if time will not serve World War II Revisionism, nothing is on its side. There is little prospect of any immediate triumph.

The foremost product thus far of Revisionist writing produced primarily for the record is James J. Martin's American Liberalism and World Politics, 1931-1941 (1964). While the book is no literary Paul Revere, likely to arouse the countryside to the menace of the historical blackout, it is a monument of careful research and assembles massive and relevant documentation that could surely provide a vast amount of fuel for future firebrands, if any should arise to ride or write. Moreover, as Felix Morley put it, the book "is written with a wit and pleasant phrasing which all too seldom spice the stodgy puddings of extensive research."

The reaction to the Martin book amply demonstrated that the literate anti-Revisionist and non-Revisionist public was not yet ready even for history written for the record, and at the same time underlined the need for such material if there is to be any hope for the ultimate triumph of Revisionism.

Among the newspapers, the New York Times followed their pattern of many years, despite my personal appeal to the editor of the book review section to give the book adequate if critical attention. They gave it to Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., and he did his usual artistic job on it, carefully evading the facts. He questioned only one specific fact, namely, whether the word "thusly" has lexicographical authenticity, and even on this matter Martin was right.

As was to be expected, the only favorable comments in important newspapers that came to my attention were in those that had favored our non-intervention before Pearl Harbor and had espoused Revisionism after the war. The New York Daily News praised it on 23 February 1965 in what was for them a long editorial, on the ground that it was needed as an effective rebuke to the liberals who had dominated American public opinion far too long. The book was very compactly and effectively reviewed by William Henry Chamberlin in the Chicago Tribune on 4 April. He commended the key burden of the book, namely, that the liberals had emphasized, if not exaggerated, the threat of national socialism and fascism to democratic institutions while neglecting the equal menace of communist ideology and methods. Walter Trohan praised the book in his Tribune column for its effective revelation of the ideals and methods of the liberal commentators. Unfortunately, this conservative and Revisionist approval did not encourage many of the over three million readers of the Daily News and Tribune to purchase the book and document their sentiments.

Among the journals, it would have been expected that the Nation and New Republic would give the Martin book extensive attention, if only to condemn it, since Martin had based much of his record of the liberal flip-flop from peace to war upon contributions to these two magazines. He had given his reasons for this procedure at the outset in complete and convincing manner. So far as I could detect, neither magazine gave the Martin book any notice, thus validating Chamberlin's conclusion that Martin "probably knows more about the New Republic and Nation during the pre-war decade than their present editors."

But Carey McWilliams, the present editor of the Nation, moved over to the lively liberal journal of Los Angeles, Frontier, to administer a lengthy smear under the fantastic title, "Mumbo Jumbo: the Fantasy World of the Far Right," although he knew, or should have known, that Martin was as critical of the far right fantasies as McWilliams, himself. He devoted the core of his criticism to pooh-poohing Martin's emphasis on the importance of the Nation and New Republic, although the reasons for Martin's doing so were indicated at length in the opening portion of the book. This was a distinction which these journals were only too proud to claim throughout the decade of the 1930's. He wound up with a concluding smear to the effect that the book had been produced in part as a result of a grant by a foundation known for its assistance to the writing of Revisionist books. He could hardly have expected it to be aided by the Rockefeller Foundation, which financed the colossal Langer and Gleason whitewash of Roosevelt's foreign policy during this period, or the Rand Corporation, which backed the Wohlstetter book.

Richard Whalen reviewed the book fairly in the National Review, although he was skeptical of writing mainly for the record and stressed, as was noted at the outset of this article, the need for a brief and clear account of how the United States got into the second World War. He fully recognized the research and scholarship involved in producing the book.

The best review typically expressing the reaction of interventionist liberals was that by Professor Paul F. Boller in the Southwest Quarterly, summer, 1965. He sought to read into Martin's book the assumption that the author held that fascism is to be preferred to communism, although Martin expressed no such opinion. He merely recounted the attitudes and opinions of the liberals who performed the flip-flop, which did indicate their apparent preference for communism, or at least their failure to be conscious of its threat to peace and the democratic way of life. But Boller did not write off the importance of Revisionism as a means of promoting peace, and he did give the book the extended consideration that its research and scholarship deserved. The review was about the best that could be expected from a wounded liberal ideologist.

Far the best review was that by the distinguished publicist and educator, Felix Morley, in the Modern Age, summer, 1965. Morley described what Martin actually wrote, indicated its import for understanding the past and dealing with the future of world affairs, analyzed the amazing liberal flip-flop and its importance in producing the rise of the war spirit, and intelligently evaluated the significance of the book. Recognizing the historical importance of a full treatment for the record, he also agreed with Whalen as to the need for a condensed version and urged the preparation of a paperback edition which would provide this and thus make possible a wide circulation of the book. Morley properly called attention to the danger that the cold warriors of today may be providing a flip-flop comparable to that of the liberals in the 1930's through the conservative shifting from nonintervention into an increasing obsession with the dangers of communism, a point of view also stressed by Herbert C. Roseman in his excellent review of the Martin book in the Rampart Journal, summer, 1965.

From the standpoint of historical scholarship, the most disheartening episode connected with the publication of the Martin book was the manner in which the book was handled by the foremost historical journal in the country, the American Historical Review, January, 1966. Taking for granted the unremitting anti-Revisionist policy of the Review for virtually a quarter of a century, one would have expected an unfavorable review and could even have respected such consistency. But here was a book which actually constituted one of the most scholarly, informing, and impressive contributions to the history of political policy, journalistic methods, and international affairs made during the present century. It surely deserved at least a two-page review, however bitterly attacked, provided that substantial explanations were given for the criticism, as Professor Boiler did give. Instead, the book was handed over to Professor Robert H. Ferrell of Indiana University, well known as an inveterate anti-Revisionist. The book was given summary treatment, the quality of which is apparent from his appraisal of the book as "an impossible goulash" and a "scholarly disaster." All this was in faithful accord with the traditional historical blackout. But the half-page "review" also indicated the growing acceptance of the Germanophobia of the historical smotherout by describing the National Socialist regime as "the most amoral government since the statistically clouded time of Genghis Khan." At least, the treatment of the Martin book by Ferrell presented an instructive synthesis of the main items in the current equipment and techniques of anti-Revisionist historical opinion today; the historical blackout, the smotherout, and making the test of acceptable historical prose whether it constitutes pleasant reading for approved historians and their brainwashed public.

The review also carried with it an ironical aftermath. Professor Martin wrote the editor a sprightly but courteous letter of protest about the Ferrell review, but received a reply which feigned shock, indicated that the letter was in bad taste, and implied that it could not be remotely considered for publication. It was not.

The allergy of most of the professional historians to the Martin book is easy to understand. By the time that the book appeared, the most generally accepted test of the worth and acceptability of a historical book of a controversial nature had become the question of whether or not it made pleasant reading to the historical guild. Since the latter was made up primarily of liberals who were war-minded in the late 1930's, or had been brainwashed later on, there is little doubt that the Martin book provided about the most unpleasant reading contained in any book published in this generation.

Some of us who went through this struggle against the war groups in the 1930's, such as Charles Austin Beard, Norman Thomas, Stuart Chase, General Charles Lindbergh, Edwin M. Borchard, John Chamberlain, John Flynn, Edmund Wilson, Sidney Hertzberg, Frank Hanighen, Jerome Frank, Quincy Howe, Hartley Grattan, Frank Chodorov, Oswald G. Villard, Marquis W. Childs, Selden Rodman, Burton Roscoe, Fred Rodell, Maurice Hallgren, Hubert Herring, George R. Leighton, Ernest L. Mayer, Dorothy D. Bromley, and the like, have known the facts by personal experience. But not even participants can know the whole story unless they have read the Martin book, and every American has much at stake in reading and digesting it. To revert to the title of John Kenneth Turner's pioneer work on World War I, Shall It Be Again?, the issue of whether the unparalleled public crime of the latter half of the 1930's shall be repeated may well hold within itself the destiny of the human race.

The historical blackout is replaced by the historical smotherout

For Revisionism to entice and instruct the newly matured generation, as suggested by Mr. Whalen, is, indeed, an exciting enterprise and might prove a very fruitful possibility to explore were it not for a crucial recent shift in the strategy of anti-Revisionism which seems to be rather generally unrecognized even by some of the veteran proponents of Revisionism, although they are virtually buried under evidence of the change by the material constantly presented by every communications agency in the country.

For some fifteen years after V-J Day, the opponents of World War II Revisionism were content to oppose Revisionist scholarship and publication by giving books the silent treatment, or smearing authors and books and belittling Revisionist scholarship. Despite such unfair procedure and the handicaps it imposed on World War II Revisionism, the Revisionists in time won the battle of factual demonstration hands down. Moreover, it was recognized that the traditional procedure of sniping, smearing, misrepresentation, and distortion in attacking traditional Revisionist works was becoming tedious, repetitive, frenetic, and often self-defeating in its fervor and misrepresentation, as was so well demonstrated by the review of the Martin book in the New York Times of 25 April 1965, by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. Hence, it was gradually but effectively decided to jockey the techniques of the historical blackout around into such a pattern that all but the most courageous and defiant Revisionists could be "shut up" entirely and rapidly and their products could be made to appear essentially irrelevant.

It was the Eichmann trial of 1960 which furnished an unexpected but remarkably opportune moment and an effective springboard for stopping World War II Revisionism dead in its tracks. As the courageous Jewish publicist, Alfred Lilienthal, has shown in his lucid book, The Other Side of the Coin (pp 104-111), this trial revealed and demonstrated an almost adolescent gullibility and excitability on the part of Americans relative to German wartime crimes, real or alleged, and the equally apparent passionate determination of every type of American communication agency to exploit the opportunity for financial profit by placing every shred of both fact and rubbish connected with them before American readers, hourly and daily, for months, if not years, on end. Not even the sophisticated Esquire or New Yorker remained immune.

This revamped historical blackout, now become the historical "smotherout," is based chiefly on the fundamental but unproved assumption that what Hitler and the National Socialists did in the years after Britain and the United States entered the war revealed that they were such vile, debased, brutal, and bloodthirsty gangsters that Great Britain had been under an overwhelmingly moral obligation to plan a war to exterminate them. Following up this contention it was asserted that the United States was compelled to enter this conflict to aid and abet the British crusade as a moral imperative that could not be evaded but was an unavoidable exercise in political, social, and cultural sanitation.

The fundamental error in this ex post facto historiography was pointed out by A. J. P. Taylor in his interview with Professor Eric Goldman in the autumn of 1965. But it is doubtful if one American in a million has ever heard or read this exchange. Even though he has never attempted to deny the fact that he is a persistent Germanophobe, the smotherout proved too much for Taylor to swallow, although he admitted his Germanophobia in the interview. As Taylor explained to Goldman:

You must remember that these gas chambers came very late. People often talk as though they were implicit in Hitler's policy from the beginning. They were, in fact, a reprisal against our British policy of indiscriminate bombing. Hitler said, again and again, "If you are just going to go out and rub out German women and children, I'll take care that all the—not only Jews—but people of many lower races are rubbed out." And when I consider that the great powers and governments . . . the American government, the Soviet government, are now both cheerfully contemplating the obliteration of ten, twenty million people on the first day of war—you see gas chambers are nothing in comparison.

All alert and aware Revisionists should and always have expressed their deep regret and repugnance over whatever brutalities were actually committed by Hitler and his government, either before or after 1939, but they have also called attention to the demonstrable fact that the number of civilians exterminated by the Allies, before, during, and after the second World War, equaled, if it did not far exceed, those liquidated by the Germans, and the Allied liquidation program was often carried out by methods which were far more brutal and painful than whatever extermination actually took place in German gas ovens.[6]

These embarrassing facts are almost invariably suppressed in the same agencies of communication that are now incessantly portraying the allegedly unique abominations of the Germans. When pressed into a corner, which is a very rare opportunity indeed, the new smotherout vintage of anti-revisionists contend, or at least imply, that it is far worse to exterminate Jews, even at the ratio of two Gentiles to one Jew, than to liquidate Gentiles. For Revisionists to controvert this assertion in behalf of nonpartisan and nonracial humanitarianism exposes them to the charge of anti-Semitism, which, in the present state of sharply conditioned and persistently inflamed public opinion, is deemed to be rather worse than parricide or necrophilia.

No substantial or credible Revisionist believes that two wrongs can make a right or that revelation of the actual Allied genocide will solve the problem of averting future wars. But the recognition that the wartime barbarism was shared would put the responsibility where it belongs, namely, on the war system which, as F. J. P. Veale demonstrated so forcibly in his Advance to Barbarism, is becoming ever more barbarous and lethal. In a nuclear age, war will, as Taylor pointed out, provide in the course of its normal operations more hideous destruction of human life than has ever been alleged in the wildest flights of imagination of the smotherout addicts. One giant hydrogen bomb dropped over a major urban center would be likely to obliterate at least six million lives, and in our eastern seaboard towns hundreds of thousands of the victims would be Jews.

This is where World War II Revisionism stands today. It was difficult enough when Revisionists were merely accused of bias, folly, incompetence, or all three. To be accused of anti-Semitism today is far more precarious than to be accused, or even proved, to be guilty of pro-communism.

Interestingly enough, an attempt is now seeming to be made to push this Germanophobia back into the causes of the first World War, if we may judge from a long article on "How We Entered World War I" in the New York Times Magazine of 5 March 1967, by the brilliant stylist and historical popularizer, Barbara W, Tuchman, granddaughter of Henry Morgenthau, whose fanciful "story" played so unfortunate a part in encouraging the war guilt clause of the Versailles Treaty and thus helped to bring on the second World War. She had followed in her grandfather's steps by producing another fanciful story in her book, The Zimmermann Telegram (1958), which she has been unwise and audacious enough to reissue recently.

It was the New York Times Current History Magazine that requested me some forty-three years ago to summarize the historical facts which dissipated the myths of wartime propaganda about the first World War, of which Ambassador Morgenthau's Story was a leading item and had been devastatingly exposed as a fraud by Professor Sidney B. Fay in the American Historical Review in 1920. My article was published in Current History in May, 1924, and first put World War I Revisionism before the literate American public in an effective manner. Whatever may have been the purpose of the New York Times in publishing this article by Mrs. Tuchman, it does raise the question of the reality of "progress" so far as the historical perspective of the Times is concerned.

This article has aroused much indignation on the part of even moderate or dormant Revisionists but it failed to excite me. In my opinion, Mrs. Tuchman is the type of writer who, given enough rope, will hang herself, and she has certainly been taking a lot of rope recently in writing about Wilson and Freud in the Atlantic (February 1967) with no evident technical knowledge about either, and even posing as an expert on historiography in the Saturday Review (25 February 1967) although expert historians like Klaus M. Epstein, A. J. P. Taylor, and David Marquand, in reviewing her much publicized The Proud Tower, have questioned her capacity to write history. In my long review of her book in The Annals, November 1966, I at least conceded her rare ability as a popularizer of social history.

More ominous is the announcement of a book by Alton Frye (Nazi Germany in the American Hemisphere, 19331941, Yale University Press), sponsored by the Rand Corporation which launched the much-publicized effort of Roberta Wohlstetter to blur out essential facts about Pearl Harbor. This book contends that, after all, Hitler did have designs on the United States and envisaged plans for invading and occupying this country—reminiscent of Roosevelt's canard about Hitler's time-table for penetration to Iowa which figured prominently in the interventionist propaganda prior to American entry into the war.

In my opinion we are in more danger from the prospect that to Germanophobia may now be added a revival of Japanophobia. This trend was latent in the anti-Revisionist writings on Pearl Harbor by Walter Millis, Herbert Feis, Langer and Gleason, Robert J. C. Butow, Samuel E. Morison, and Robert H. Ferrell in their defense of Roosevelt. But it has just now taken a more definite form in Ladislas Farago's The Broken Seal: The Story of "Operation Magic" and the Pearl Harbor Disaster (1967), in which the Japanese efforts to preserve peace by negotiation are presented as a hypocritical sham to cover up their actual determination on war and to gain time to prepare for it. A more extended enterprise in this same vein has been foreshadowed by Gordon W. Prange. We may be on our way to returning to Admiral Halsey's view of the Japanese as sub-human anthropoids.

It is quite true that if they could be exposed to the facts about the causes of the second World War and our entry on their merits, free from the all-encompassing and incessant barrage of Germanophobia, notably that against National Socialist Germany, this generation of his own age to which Mr. Whalen refers is actually highly vulnerable and receptive. This I have demonstrated to my own satisfaction through the response to my lectures before student groups in first-rate American universities and colleges, and in such articles as those I wrote in Liberation in the summers of 1958 and 1959, in the New Individualist Review in the spring of 1962, and in the Rampart Journal, Spring, 1966, thus covering both the left and right of this new generation.

We can, however, hardly expect those persons who might be willing to learn, if they had a fair chance, to withstand the incessant bombardment by our communication agencies designed to demonstrate that we had a vital moral and self-protective duty to favor and enter a war fought to rid the world of a gang of barbarians more dissolute and bloodthirsty than anything since, or even before, Genghis Khan and Tamerlane.

This younger and brainwashed generation gets into contact with only scattered and tiny bits of even the traditional Revisionist material, and this at considerable intervals. But not a day goes by without one or more sensational articles in the daily papers about the exaggerated National Socialist savagery which required our entry into the war; the leading weekly and monthly journals, especially Look and the Saturday Evening Post, 7 never miss their quota of this lurid prose; the radio has it on the air daily; expensive moving pictures are devoted to it; not a week goes by without several inciting television programs revolving around this propaganda, and sensational books pour forth at frequent intervals. While reading some of the most repulsive examples of such smotherout Germanophobia, I noted in the newspapers and journals pictures of President Johnson apparently posing without a shudder as the host of the Ethiopian tyrant and genocidal virtuoso, Haile Selassie, who had previously been invited, or at least permitted, to appear in the funeral cortege of President Kennedy.

Lest the public get "fed up" and bored by repetition, the material handed out to them has to be made more unceasing, exaggerated, and inflammatory. There should be some limit to this but it certainly is not in sight, as yet, even though it far exceeds in frequency, volume, and ferocity anything handed out in wartime, when the public imagination was occupied in large part by following military operations.

There would appear to be no restraining memory of the backwash that followed when the mendacity and exaggerations of the Bryce Report on alleged German atrocities in the first World War were revealed by Arthur Ponsonby, J. M. Read, and others. The foremost authority on the subject has estimated that the number of Jews exterminated by the National Socialists, already reported by "authorities" cited by the smotherout for all the wartime German concentration camps, would amount to well over twenty-five millions. This does not include the upwards of a million allegedly killed by the German Einsatzgruppe when battling guerrilla warfare behind the lines. We are now being told (New York Times, 3 November 1966, and Saturday Evening Post, 25 February 1967) that the Austrians executed about as many Jews as the Germans. With not more than fifteen to eighteen million Jews in the world to start with in 1939, this is, indeed, a remarkable genocidal achievement, especially if one considers the logistical problems involved in its execution. The truth about German operations, if presented along with Allied brutalities, provides a sufficient indictment without any need for fantastic exaggerations which open the way for a devastating backwash, if and when the truth is presented in this or some future generation.

If a Revisionist work on the second World War were written with a combination of the scholarship of Sidney Fay and the persuasive stylistic genius of Millis and Chamberlin, the smotherout answer would be that the impressive facts of diplomatic history since 1930 which have been adduced and presented by Revisionists with conviction, force, and vigor are now only antiquated and irrelevant trivia. What is deemed important today is not whether Hitler started war in 1939, or whether Roosevelt was responsible for Pearl Harbor, but the number of prisoners who were allegedly done to death in the concentration camps operated by Germany during the war. These camps were first presented as those in Germany, such as Dachau, Belsen, Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen, and Dora, but it was demonstrated that there had been no systematic extermination in those camps. Attention was then moved on to Auschwitz, Treblinka, Belzec, Chelmno, Jonowska, Tarnow, Ravensbrück, Mauthausen, Brezeznia, and Birkenau, which does not exhaust the list that appears to have been extended as needed.

An attempt to make a competent, objective, and truthful investigation of the extermination question is now regarded as far more objectionable and deplorable than Professor Bemis viewed charging Roosevelt with war responsibility. It is surely the most precarious venture that an historian or demographer could undertake today; indeed, so "hot" and dangerous that only a lone French scholar, Paul Rassinier, has made any serious systematic effort to enter the field, although Taylor obviously recognizes the need for such work and hints as to where it would lead. But this vital matter would have to be handled resolutely and thoroughly in any future World War II Revisionist book that could hope to refute the new approach and strategy of the blackout and smotherout contingents.

Even former ardent Revisionist writers now dodge this responsibility, some even embracing and embellishing the smotherout. The most conspicuous example is that of Eugene Davidson, who once had the courage to place in jeopardy his position as head of the Yale University Press by publishing Charles Austin Beard's two forthright Revisionist volumes. In his Death and Life of Germany (1959), Davidson defied Burke's warning against indicting a nation and proceeded to indict Germany since 1932 on the basis of the Diary of Anne Frank without even remotely suggesting any question about its complete authenticity. His recent The Trial of the Germans: Nuremberg (1966) is providing no end of aid and comfort to the smotherout contingent, as evident immediately by the ecstatic review of the book in Newsweek, 9 January 1967.

The Davidson book is devastatingly reviewed by A. J. P. Taylor in the New York Review for 23 February 1967. As Taylor puts it: "The hypocrisy of Nuremberg was revolting enough in 1945. It exceeds all bounds when it is maintained in 1967, over twenty years afterwards. Mr. Eugene Davidson has compiled at enormous length a biography of the accused at Nuremberg. Here they are, from gorgeous Göring down to insignificant Fritzsche, the radio commentator. The biographies are pretty sketchy, slapdash stuff hatred up in a flashy style and evidently assuming that any kind of rubbish is good enough for such scoundrels. It is really rather hard that the thing should be done so badly. After all these years, there are some things perhaps worth discussing." The remaining comment on Nuremberg by Taylor is perhaps the best brief appraisal that has ever been written of its combination of bias, hypocrisy, and legalized imbecility. Taylor had previously written in the London Observer: "It is strange that an English Judge should have been found to preside over the macabre farce of the Nuremberg Tribunal; and strange that English lawyers, including the present Lord Chancellor, should have pleaded before it."

The treatment of Davidson and Nuremberg by Taylor is part of his analysis of three books which represent the upper level of the smotherout literature, and what he has written about them probably required more courage and integrity than was needed to produce his Origins of the Second World War. It is the first overt attack made by any historian, currently highly esteemed, on the smotherout attitudes and methods, and it may be hoped that it has set a healthy precedent. It is an invaluable and equally indispensable sequel to his Origins. So long as the smotherout prevails, Taylor's conclusions in that book about responsibility for the outbreak of World War II will be passed off as irrelevant antiquarianism, no matter how accurate.

While the smotherout deluges us with exaggerated examples of National Socialist savagery, there is no comparable interest in, or even knowledge of, the actual Allied barbarities, such as the Churchill-Lindemann program of saturation bombing of civilians, especially the homes of the working class, which was as brutal, ruthless, and lethal as anything alleged against the Germans. As Liddell Hart and others have made clear, Hitler had honestly sought a ban on all bombing of civilians apart from the accepted rules of siege warfare. The German bombing of Coventry and London took place long after Hitler failed to get Britain to consent to a ban on civilian bombing. The incendiary bombing of Hamburg and Tokyo and the needless destruction of Dresden are never cogently and frankly placed over against the doings, real or alleged, at Auschwitz. The atomizing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, completely needless to secure Japanese surrender, are all but forgotten, save when occasionally defended by former-President Truman or made the basis of a romantic moving picture.

Little or no mention is now made of the fifteen million Germans who were expelled from their eastern provinces, the Sudeten area, and other regions, at least four millions of them perishing in the process from butchery, starvation, and disease. This was the "final solution" for defeated Germans who fell into the hands of the victors and, interestingly enough, as Ragsinlet has made clear, it was identical with the "final solution" planned by Hitler and the national Socialists for the Jews, in the event that Germany won World War II. The smotherout legend represents the German plan as the extermination of all Jews that the Germans could lay their hands on. No authentic documents have been produced that support any such contention. The National Socialist "final solution" was a plan for the deportation of all Jews in their control at the end of the war, Madagascar being one place considered. Even if they had been victorious, the Germans could not have laid hands on more than half as many Jews as the number of Germans who were deported from their homelands.

The wholesale massacre of Polish officers and leaders at the Katyn Forest and elsewhere by the Russians, the exterminations and expulsions in the Baltic countries, and the rounding up of some millions of Russian soldiers and other anti-communist refugees in Germany after the war, to be turned back with Eisenhower's consent to Stalin for execution or the even worse enslavement in Russian starvation labor camps, are conveniently overlooked. Nor is anything said about the fact a Yugoslav scholar, Mihajlo Mihajlov, has recently, on the basis of Russian documents, disclosed that at least twelve million Russians passed through Stalin's concentration camps, with not more than half of them surviving. The intolerable Morgenthau Plan, approved by President Roosevelt, which envisaged the starvation of between twenty and thirty million Germans in the process of turning Germany back into an agricultural and pastoral nation, has now become no more than a subject for esoteric economic monographs. Only one adequate and accurate book of even this type, that by Nicholas Balabkins, Germany Under Direct Controls (1962), has so far appeared in English, and this has been unduly neglected or ignored.

Also overlooked today is the fact that virtually the entire Japanese population of the Pacific Coast were dragged out of their homes without provocation or the slightest need from the standpoint of our national security. The recent able and revealing book of Allan R. Bosworth, American Concentration Camps (1967), may redirect American and world attention to this scandalous episode, which was mainly the result of the brainstorm of Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson.

The above are a few of the facts and considerations that would have to be presented with adequate thoroughness in any World War II Revisionist book which could hope to counter the current smotherout pattern of anti-Revisionism.

Another obstacle lies in the fact that, as a result of brainwashing and indoctrination for a quarter of a century, the American public is not only ignorant of the facts involved in the smotherout approach but has lost much of the traditional national self-respect and public pride that controlled its reactions after the first World War. It remains my well-reasoned conviction, based on unexcelled experience, that the general acceptance of Revisionism in the late 1920's and the early 1930's was due more to public resentment at the "Uncle Shylock" slurs from abroad and the reneging of our former Allies with respect to the payment of their war debts than to all the Revisionist writings of the era.

This once-powerful impulse, arising from national pride, apparently no longer operates in this country: the American public has by now become thoroughly immune to the "Yanks Go Home" and comparable ungrateful epithets of our former Allies, and to the hostility and ingratitude of those who have taken our more than a hundred billion dollars in foreign aid and other public largesse since 1945, to say nothing of the previous lavish wartime aid.

When the Revisionists, after the first World War, revealed how we had been lied to by gentlemen in British intelligence and propaganda work, such as Sir Gilbert Parker, there was a considerable backwash and much public indignation. When H. Montgomery Hyde published his book, Room 3603, not only revealing but boasting of how we had been kicked around by Sir William Stephenson (the "Quiet Canadian") and his British intelligence goons, even to the extent of trying to break up anti-interventionist meetings in this country in 1940-1941, there was hardly a ripple. The book attracted little attention, was usually commended when noticed at all, and received virtually no shocked condemnation.

When the conflict was over, the American public warmly supported the exposure of the anti-German propaganda of the first World War, such as the Bryce Report, by Mock and Larson and others, but there has been no public or historical demand for an equally honest and searching investigation of the far more sweeping and debatable propaganda relative to alleged German barbarism during the second World War. Even to suggest the desirability of any such project would place the sponsor in professional, if not personal jeopardy.

Nor do we get any assistance or encouragement from the masochistic West Germans who, if anything, in their own blackout distortions and smotherout exceed the indictment of wartime Germany by their former enemies. This is the result of the German self-flagellation and self-immolation, in sharp contrast to the ardently Revisionist proclivities of the Weimar Republic. Nevertheless, but perhaps fittingly, the West Germans get little credit even for this craven attitude. There are surely abundant reasons why all of us who lived through the barbarities of the second World War and its aftermath should be ashamed of being members of the human race but certainly there is no sound basis for any unique German shame or self-flagellation.

History relative to the second World War has now become a public propaganda enterprise rather than a historical problem. It has passed from the investigation of documents and other traditional historical evidence into a frenzied public debate over extermination archeology, comparative biology, clinical pathology, and genocidal ethics, in which only one side has any decent opportunity to present its arguments and evidence. This diversified and confused conglomeration of fancy, myth, mendacity, vindictiveness, and fraudulently unilateral vengeance surely provides no safeguard against the development, increasing imminence, and destructive potential of a nuclear holocaust.

About the only rays of light and hope on the horizon for the moment are byproducts of the Vietnam War. For the first time in all American history, except for the Mexican War landgrab, the liberals are not the shock troops of the warmongers, and many are preponderantly "doves," notably the younger liberals or the "new left." This has encouraged many of them who, as a group, have been less subject to the World War II brainwashing, to look back over their shoulder at liberal bellicosity in the past and examine its validity more rationally. This has already made many of them skeptical about the impeccable soundness of interventionist propaganda and the historical blackout relative to the two world wars of this century. I have had more reasonably friendly and apparently honest inquiries about Revisionism in the last two years than in the previous twenty. This skeptical and inquiring attitude may grow; if so, it would have little patience with the assumptions, methods, and literature of the smotherout.

Even more promising and potentially helpful has been the growth of the "credibility gap" with reference to the Vietnam War, primarily the gap between what Charles Austin Beard once designated as "the appearances and the realities" of administration assertions and assurances about our official policies in entering, continuing, and escalating the war. This has especially impressed the liberal doves upon whom we must place our main hope in exposing and rebuffing the smotherout. Nothing would so quickly dissolve the smotherout as to apply to its attitudes and contentions the skeptical implications of the credibility gap. The smotherout would be hopelessly vulnerable to even a moderate application of the credibility-gap approach; it could fall apart quickly and hopelessly. Hence, we may appropriately, if with no premature assurance, welcome the growth of the credibility gap now being nursed and nourished by the Vietnam War.

May it grow, prosper, and dispel the smotherout, but its lessons should not all be derived from the statements and actions of the Johnson administration. It should lead those amenable to fact and reason to turn back to the credibility gap in the pre-war protestations of Wilson and Roosevelt, the latter being the most voluminous and impressive of all, and to the credibility gap in Truman's assertions about the necessity of bombing the Japanese cities and entering the Korean War, which even General Bradley designated as "the wrong war, in the wrong place, and at the wrong time." The credibility gap in the position and protestations of the cold warrior "hawks," as pointed out by D. F. Fleming, John Lukacs, F. L. Schuman, David Horowitz, Murray N. Rothbard, James J. Martin, and others, is even more grotesque and fictitious than that of the Johnson administration relative to Vietnam, but fortunately, it does not as yet possess full official status and authority.

Hence, let us hail the credibility gap, whether derived from the doves, the hawks, the cold warriors, or the Johnson administration and its predecessors. Its application to the smotherout provides the only hope on the horizon today of making Revisionism effective in gaining access to public opinion and policy and thus working for permanent peace.

Endnotes

1. National Review, 20 April 1965, pp 335-336.

2. See Select Bibliography of Revisionist Books.

3. Journal of Modern History, March 1948, pp 55-59.

4. Especially in the Rampart Journal, Spring 1966.

5. Broadcast then over the Goldman "Open Mind" Program, WNBC-TV, and rebroadcast on the "World Topic" program on 2 January 1967.

6. (Of course, Barnes is confused here by the difference between a "gas chamber" and a "gas oven." Shortly after writing this article, he came to reject the entire Holocaust myth, not just part of it.)

7. Especially many entries in Look, the latest being 21 March 1967, and in the Saturday Evening Post, see 22 October 1965