AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

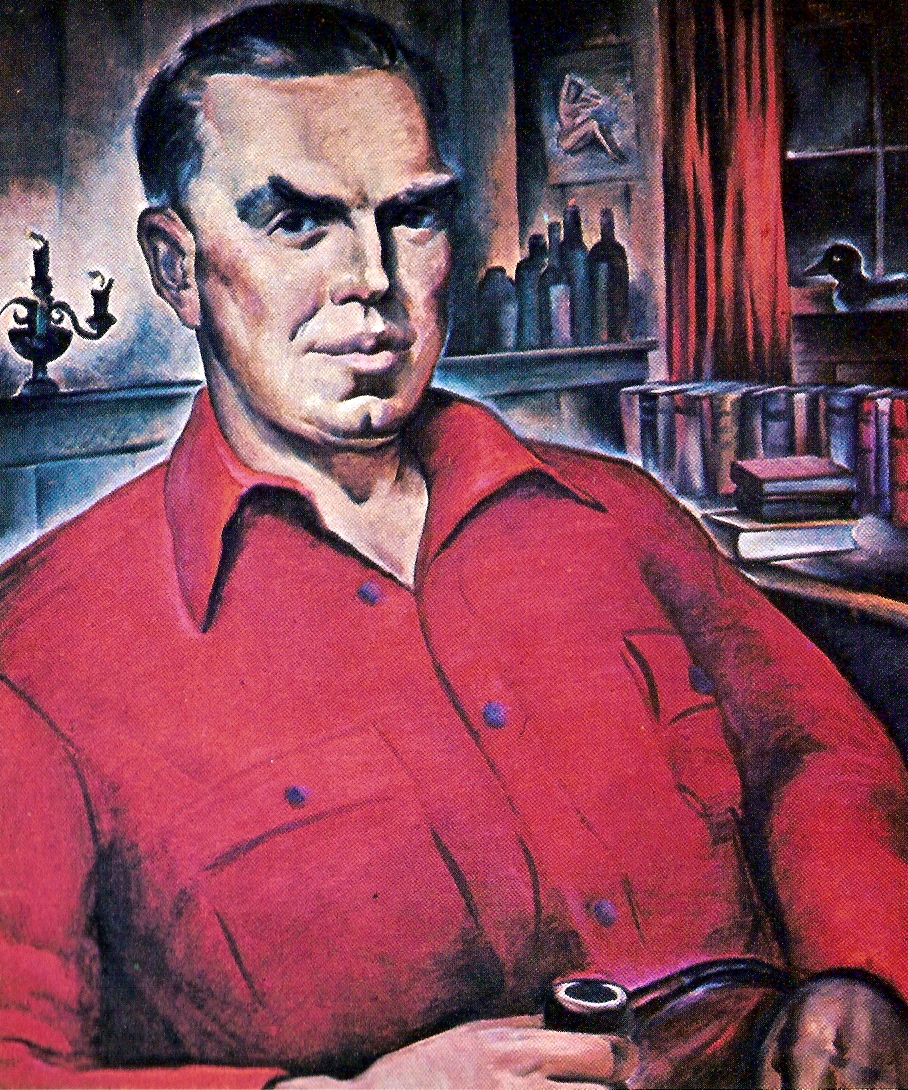

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

From The American Academy of Political and Social Science, 175, September 1934, 11-18. In 1934 Barnes views the “Hitler movement in Germany” as “a menace to European peace,” but insists that it “could not conceivably have arisen to power except upon the wave of resentment in the minds of the German people against the war-guilt charge and the punitive measures which have grown out of it.”

Appended to this prophetic interbellum article is this author description: “Harry Elmer Barnes, Ph.D., has been editorial writer for Scripps-Howard newspapers since 1929, and is a lecturer and debater in this country and abroad. He has been on the faculty, in the departments of history and sociology, of Syracuse University, Columbia University, Clark University, New School for Social Research, Smith College, and Amherst College. In three books: The Genesis of the World War, In Quest of Truth and Justice, and World Politics in Modern Civilization, and in many articles, he has devoted his attention specifically to the problem of war guilt and its bearing on current world politics.”

The Public Significance of the War Guilt Question

Harry Elmer Barnes

There are many sane, sensible, and informed people who believe that we should discourage discussion of the war-guilt question on the general ground that it is better to let sleeping dogs lie in peace. They hold that to bring up the question of war responsibility only revives war hatreds and postpones the desirable healing process which must precede any permanent peace. They claim that it is best to forget the war propaganda and Versailles and to put our trust in the League, Locarno, and the Kellogg Pact.

Most reasonable persons will agree that world peace is a larger and more important issue than settling the question of who started the World War. If it could be shown that silence upon the question of war guilt would hasten and assure world peace we might remain silent, however great the moral injustice to the Central Powers.

It appears to the writer, however, that the position of those now opposed to a discussion of the causes of the war is illogical and untenable. There can be no hope of establishing peace in Europe until the moral and material injustices of the Treaties of Versailles, Saint-Germain, and Trianon are undone and Europe is reconstructed in harmony with justice and decency. The plant of Locarno cannot flourish in the pot of Versailles. The facts and the principles underlying these two settlements are irreconcilably opposed.

One can scarcely look for peace in a Europe with no adequate international organization, when thirty national states threaten peace instead of the eighteen which existed in 1914. A settled state of affairs could hardly be expected to develop when Germany and her allies were disarmed and compelled to pay crushing indemnities on the ground of their sole responsibility for the great conflict, while the Entente Powers, armed to the teeth, endeavored to reduce or evade altogether their pecuniary obligations to the United States on the assumption that they saved us from perpetual slavery under the heavy hand of the Hun.

The crying injustices of Transylvania, the Tirol, Bessarabia, Macedonia, the Polish Corridor, the Saar, and Silesia, to mention but a few of the more atrocious fruits of Versailles, must be rectified before Europe can aspire to permanent peace. Otherwise, the oppressed nations will but await a more favorable alignment of European powers to renew the vain attempt to secure justice by deceit and force.

The Story of the Allies

The full import and significance of the war-guilt controversy cannot be apparent unless we are completely aware of the revolution in historical interpretation which has taken place in the last decade and a half with respect to this question.

The Entente epic of 1914-18 ran essentially as follows: For years prior to 1914, France, Russia, England, and their associates had been working steadily for the peace of Europe and a concert of nations. But they had been blocked at every turn by German bluff, aggression, and ill will. Germany was impatiently awaiting the arrival of Der Tag, when she would overrun all Europe as she had France in 1870-71. She had built up a colossal and unmatched military machine, having become nothing less than a great military octopus threatening the peace of the world.

Der Tag came when the Archduke Francis Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was assassinated at Sarajevo on June 28, 1914. It was even asserted by some Entente writers that this assassination was plotted by militarists in Germany and Austria who could tolerate no further delay.

Immediately the Allied states tried to hold the situation in check by diplomatic measures, but Germany spurned them all. When her ally, Austria, seemed likely to listen to reason, Germany threw everything to the winds and plunged Europe into blood and ruin through a premature and utterly unprovoked declaration of war on Russia. Turning westward, she declared war on France and invaded the defenseless little neutral state of Belgium, thus transforming the solemn obligations of nations into scraps of paper.

The allied states, thus suddenly surprised in an ambush attack by the German “gorilla,” reluctantly but gallantly took up the sword in self-defense. England came in solely to champion the cause of “poor little Belgium” after she had exhausted every resource of diplomacy and persuasion. The war, thus begun with clean hands on the part of the Entente, was carried on as a noble and idealistic enterprise. There was no thought of territorial or financial aggrandizement. The Allies fought for the sanctity of international law, for the rights of small nations, for the end of military dictatorship, for the freedom of the seas, for democracy, and for world organization to prevent another season of carnage. There were no secret agreements among them. All was aboveboard and exposed to the clear noonday light of truth and sincerity. Never before had so many states united to shed their blood in the cause of pure and limpid idealism.

On the other hand, Germany continued her brutality after the fashion of her brazen acts in the summer of 1914. She reduced war to the lowest level of savagery, not only crucifying captured soldiers, but even brutally and wantonly assaulting, mutilating, and murdering non-combatants, many of them women and children. German submarines transferred the barbarism from land to the waters, turning their guns on the poor devils who were struggling to keep afloat.

This pretty myth might have been believed for generations had not revolutionary overturns in Germany, Austria, and Russia permitted the publication of the secret documents in foreign offices which told the real truth about 1914. They also exposed the facts about the Allied agreements after the war broke out—i.e., the notorious Secret Treaties.

The Reverse Side

We now have the actual facts about 1914. They represent a complete reversal of the Entente picture, though nobody of sense regards Germany as a snow-white and guiltless lamb in the midst of a pack of howling and badly smeared wolves.

In the decade before the war, Germany had made vigorous efforts to arrive at an understanding with Russia, France, and England, but had failed. This was partially due to the French determination to obtain Alsace-Lorraine, to the British jealousy of German naval, mercantile, and colonial power, and to the Russian desire for the Straits. It was in part due to the maladroit diplomacy of Chancellor von Bülow and his evil genius, Baron von Holstein. From 1912 to 1914, Izvolski, Russian ambassador in Paris, and President Poincaré of France carried through a diplomatic revolution which placed France and Russia in readiness for any favorable diplomatic crisis which would bring England in on their side and make possible the recapture of Alsace-Lorraine and the seizure of the Straits.

This opportunity came after the assassination of the Archduke. Germany accepted all the important diplomatic proposals of 1914 save one. For this she substituted one which England admitted was far superior. She tried to hold Austria in check after July 27, but France and Russia refused to be conciliatory. In the midst of promising diplomatic negotiations, Russia arbitrarily ordered a general mobilization on the German frontier. France had given her prior approval. This mobilization had long been admitted to be tantamount to a declaration of war on Germany. After vainly exhorting the Russians to cancel their mobilization, Germany finally set her forces in action against the numerous Russian hordes. France informed Russia that she had decided on war a day before Germany declared war on Russia and three days before Germany declared war on France. England came in to check the growth of German naval, colonial, and mercantile power. The Belgian gesture was a transparent subterfuge, used by Grey to inflame the British populace. He has himself admitted that he would have resigned if England had not entered the war, even though Germany had respected Belgian neutrality. The documents show us that Grey refused even to discuss Belgian neutrality with Germany as a condition of British neutrality. Belgium did not figure in the British cabinet discussions when war was decided upon. Lord Morley’s Memorandum on Resignation proves this.

War Aims of the Nations

In the light of the well-established facts about 1914, it is now clear that, under existing circumstances, Serbia, Russia, and France wished a European war in the summer of 1914; that Austria-Hungary wished a local punitive war but not a European war; and that Germany, Great Britain, and Italy would have preferred no war at all, but were too dilatory, stupid, or involved to act with sufficient expedition and decisiveness to avert the calamity.

In 1918 the Bolsheviks of Russia published the notorious Secret Treaties of the Allies. These proved that the idealistic Entente pretensions about the aims of their war were no more valid than their mythological assertions about the events of the summer of 1914. Russia was to get the Straits, Constantinople, and adjacent districts. France was to get Alsace-Lorraine and the left bank of the Rhine. Italy was to make the Adriatic an Italian lake. Great Britain was to be rewarded by the destruction of the German navy, merchant marine, and colonial empire. Altogether, they were to destroy the “economic power of Germany.” These treaties, of course, sent the Allied “Holy War” myth gurgling to the bottom of the sea, spurlos versenkt. Wilson tried to block their execution at Versailles, but with indifferent success. As William Allen White well expressed the facts, Wilson traded “the shadow of American ideals for the substance of European demands.”

The courageous works of Ponsonby, Avenarius, Grattan, Viereck, and others have likewise upset the war-time myths about German atrocities. It is amply proved that even the Bryce Report was consciously falsified and completely unreliable. Even Admiral Sims admitted that there was but one German submarine atrocity, and for this the German commander was punished.

This remarkable reversal of historical opinion relative to responsibility for the World War does not, of course, give Germany any ground for assuming a holier-than-thou attitude. She did not wish war in 1914 because her aspirations and policies were being remarkably well realized through peaceful channels and activities. Her pacific attitude did not grow out of her superior moral principles or a more sincere devotion to the cause of peace. Had some of her basic goals and public policies been realizable only through war, as was the case with France and Russia, there is every probability that Germany would have been just as bellicose in 1914 as were these other powers.

The Evidence

The reader may legitimately raise the question as to how we know that this so-called “revisionist” interpretation of war responsibility is any more sound or assured than the views which passed current during the war period. The answer is that we now have about all the relevant facts that will ever be known with respect to war responsibility in 1914.

The situation is wholly novel in human experience. As a result of the revolutions in Russia, Austria, and Germany, new governments appeared on the scene which had no reason for desiring to conceal the facts which might possibly turn out to be discreditable to the preceding royal regimes. Indeed, they hoped that the documents in the foreign offices would actually show that the imperial governments had been responsible for bringing on the Great War. They believed that such proof would help to maintain the revolutionary governments in power. They counted on an increased popular hatred of the older regimes from the knowledge that the monarchical governments had been responsible for the suffering which the World War had entailed.

Therefore, the Austrian and German governments voluntarily published a full and complete edition of the documents in their respective foreign offices bearing on the crisis of 1914—the so-called Red Book and the Kautsky Documents. The Germans subsequently published all the important documents on the whole period from 1870 to 1914, the Grosse Politik. These allowed the facts to speak for themselves as to German foreign policy in the half-century before the war, and challenged the other states to do likewise.

The Russian Bolshevik government did not systematically publish its documents, but allowed French and German scholars, such as Marchand and Stieve, to have access to the archives and to make adequate selections. The Stieve collection, known as Der diplomatische Schriftwechsel lswolskis, is the standard edition, and its honesty and adequacy cannot be challenged. It deals particularly with the work of Izvolski in carrying through the great diplomatic revolution of 1912-14 in collaboration with President Poincaré of France.

The Austrians were long delayed in the publication of material on the period before 1914 because of the opposition of the Entente to the appearance of such potentially damaging documents. Finally, in 1930, Austrian scholars published an eight-volume collection of source material on Austro-Serbian relations from 1908 to 1914. This has made necessary a much more lenient judgment of Austria than was possible when Professor Fay’s important work appeared in 1928.

The British Government was the first nonrevolutionary government voluntarily to publish its documents bearing on the outbreak of the World War. This it began in the autumn of 1926, and ten other volumes are in process of publication on the period from 1898 to 1914.

Finally shamed and smoked out, the French began in 1928 to publish a collection of diplomatic documents on the prewar period. The fact that the supervisory authorities are mainly public functionaries rather than impartial scholars makes it highly probable that the French documents will not possess the completeness or the candor to be observed in the earlier publications. But so much documentary material has now been published by other states which enables us to check up on the French documents that we may be certain that the colossal frauds and forgeries which characterized the original French Yellow Book will not be possible in this more extended collection of French documents.

This documentary material has been accompanied by special monographs, by biographies and memoirs of leading figures in the diplomatic history of Europe from 1870 to 1914, and by able works which have sought to assemble, appraise, and summarize the significance of the documentary evidence, the monographs, the biographies, and the memoirs. The overwhelming majority of such works, of which Professor Fay’s The Origins of the World War is an outstanding representative, reverse our war-time judgments in the manner which we have above described. Differences of opinion today relate to details rather than to the general picture.1

Practical Bearings of the War-Guilt Question

We may now consider the public significance of the revolution in our conceptions of war responsibility, and make it clear why the subject is one of high importance in the movement to create a better and more pacific era of international relations.

Punitive measures

In the first place, the peace treaties of 1919—Versailles, Saint-Germain, Trianon, and Neuilly—all rest upon the assumption of either the unique or the primary guilt of the Central Powers. The severely punitive measures embodied in these treaties are based in considerable part upon this thesis of war guilt. Therefore they not only are unjust, but provoke acute resentment on the part of the vanquished states who suffer under the yoke of these treaties. There can be no permanent peace in Europe until the vindictive system set up under the peace treaties is thoroughly modified. The Hitler movement in Germany, very generally and rightly regarded as a menace to European peace, could not conceivably have arisen to power except upon the wave of resentment in the minds of the German people against the war-guilt charge and the punitive measures which have grown out of it.

But there will be little prospect of any far-reaching revision of the Treaty of Versailles and its associated documents unless the nations of the world recognize and admit the falsity of the war-guilt verdict upon which so much of the postwar settlement really rests.

War debts and reparations

The war debt and reparations issues also turn very directly and immediately about the problem of war guilt. A major foundation of sentiment in debtor countries favoring the reduction or cancellation of the debts due to the United States is the popular belief in such states that during 1914-18 they were really fighting the battle of the United States in preserving us from a German invasion. Hence, they cannot see why we should insist upon being repaid for loans which the Entente was using to buy munitions and other goods which they employed to repel the common enemy in Europe and thus prevent the battle line from spreading to the United States. So long as the fictitious and fanciful wartime theory of the causes and the issues of the World War prevails, there is much logic in this opposition to the payment of war debts.

Once the facts are fully realized, however, a complete reversal of attitude becomes necessary. It is now apparent that the debtor countries contracted their loans from the United States under obviously false and fraudulent pretenses. Instead of joining in a crusade in behalf of justice, liberty, and fair dealing, the United States was enticed into a sordid war of European self-interest through all manner of deceit and misrepresentation.

Whatever the practical difficulties in the way of collection, it is now entirely clear that the United States has a perfect moral basis for the collection of the war debts one hundred cents on the dollar. Likewise, our cancellation of more than half of these debts between 1923 and 1926 appears an act of gratuitous international generosity without precedent in human history. Later cancellation demands on the part of the Entente take on the form of incredible effrontery.

Similarly with reparations, the war-guilt issue plays a critical part in this field of international controversy. German reparations were explicitly and definitely based on the war-guilt clause (231) of the Treaty of Versailles. President Wilson had publicly repudiated the imposition of a punitive indemnity upon Germany. Therefore reparations were represented as a moral penalty for the deliberate and willful guilt of Germany in bringing on the World War.

Once the most elementary facts about war responsibility are recognized and admitted, the very foundations drop out of the whole reparations policy, unless the Entente is frank and honest enough to admit the imposition of the old-time indemnity. The question which should have been raised after 1919 was not how much Germany could pay on the reparations account. but why she should be paying anything at all. The invasion of the Ruhr to collect reparations appears in the new perspective as an utterly unjustifiable act of military aggression. The Lausanne conference of 1932 ostensibly terminated German reparations, at least for the time being and in any large amount, on the ground of Germany’s incapacity to pay. The facts would have dictated such a discontinuance in keeping with nothing more than elementary logic and justice.

Unfriendly attitudes

A thorough and public threshing out of the war-guilt issue is also absolutely indispensable to the creation of a realistic and friendly set of attitudes in European international relations. So long as the Entente peoples are compelled to labor under the delusion that they were attacked by Germany, they are bound to maintain an attitude of fear, hostility, and resentment toward Germany and her allies. This will obstruct the development of any feeling of trust and friendship upon which some assurance of peace and good will might rest.

For example, patriotic and revengeful French leaders nurse in France the illusion that France has been three times attacked and invaded by Germany in modern times—in 1813, 1870, and 1914. This creates in the French mind a sentiment of fear and enmity which makes any real understanding with Germany either difficult or impossible. If the French people could be made to see that in the case of each of these invasions France was actually the aggressor in the war, the French people would be likely to fear Germany less and to demand a change of policy on the part of the arrogant and bellicose French statesmen and diplomats.

Until Europe faces realistically and factually the war-guilt issue, the latter is bound to remain the breeding place of errors and misunderstandings which will permanently block efforts to assure European peace.

A realization of the facts with respect to the causes and the issues of the World War should also do much to refute the dangerous illusion that peace and other noble causes can be promoted by the savage and brutal methods of warfare. The facts about the war and its results should help the cause of peace by making clear how futile it is to hope that we can end war by more war. The war spirit and methods create a psychological attitude on the part of the participants in the struggle which makes constructive, farsighted, and generous conduct at its conclusion well-nigh impossible. Statesmanship does not emerge headlong on the heels of savagery. If we desire peace it must be achieved in a period of peace, and not hoped for as the aftermath of war. The greatest words of President Wilson during the war were that there could be no permanent peace which was not a “peace without victory.”

United States needs caution

So far, we have discussed the practical bearing of the war-guilt question upon the healthy reconstruction of European international relations. But the problem has its practical bearings for the people of the United States as well. A dawning consciousness of how badly we were deceived about the actual issues in the European situation from 1914 to 1918 may serve to make us rather more cautious and hesitant about capitulating to propaganda in the event of another European cataclysm. We may be led to scrutinize evidence more closely and to a void being the victims of skillful foreign press agents and silver-tongued orators.

It would be very foolish to maintain that the Entente Powers of 1914-18 are the only ones in Europe likely to try to deceive us. All sides to any great conflict are bound to do their best to enlist our aid and sympathy. Sometime in the future, England and Germany may be united against France and Italy. If so, England’s command of the seas will give Germany that access to our attention which she was denied in 1914-18. Under such circumstances we may need to be as critical of German propaganda as we ought to have been of French and British partisanship in the Great War.

It so happens, however, that in the present instance we have to consider the manner in which Great Britain, France, Italy, and Russia deceived us as to the facts relating to the outbreak of the World War and as to the issues at stake in the struggle. An understanding of these facts certainly should do much to make us less ready to pull the chestnuts out of the fire for any European nation or coalition whatever, in the event of another world conflagration.

Conclusions

Therefore it would appear that the question of who brought on the World War is a problem of the greatest moment and the utmost timeliness. It is such: (1) because upon the lies of the war period were erected the detestable treaties which followed its close; (2) because the chief sound moral basis for revising these treaties is the truth about the causes of the World War; (3) because European peace can be secured only as a result of the revision of the treaties; (4) because a study of the facts about war propaganda from 1914 to 1918 affords the best possible protection against our being so rudely and completely deceived another time; and (5) because the results of the conflict demonstrate for all time the futility of expecting war to be ended by war, and show us that if we are to secure peace it must be worked for in a time of pacific relations.

If, by setting forth the facts about war guilt and the postwar treaties, we can arouse a sufficient wave of moral revulsion and indignation to force a revision of the treaties in harmony with facts and justice, more will have been achieved than can be hoped for from any armed conflict of whatever proportions.

1 The latest and, one may fairly say, the final desperate effort to revive and vindicate the wartime conceptions of war guilt is contained in Professor Bernadotte E. Schmitt’s The Coming of the War 1914 (1930). This has been devastatingly answered by M. H. Cochran in his Germany Not Guilty in 1914 (1931), probably the most severe criticism to which an American historical work has ever been subjected. Even those who defend Schmitt personally refute his work and conclusions by implication. For example, Professor F. L. Schuman sweepingly defended Schmitt’s scholarship and impartiality in reviewing Schmitt’s book in The Nation. At the same time, Schuman’s own work, War and Diplomacy in the French Republic, presents a revisionist interpretation wholly at variance with Schmitt. The history of war-guilt scholarship is recounted in my World Politics in Modern Civilization, Chaps. XXI-XXIII.

Posted March 9, 2008