AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

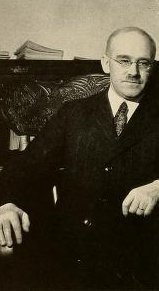

Brand Blanshard at Swarthmore (1930s?)

An excerpt Brand Blanshard, Reason and Goodness, London: George Allen & Unwin and New York: Humanities Press, 1961; Chapter XIV, “Reason and Politics,” sections 14-25, pp. 393-408. I have removed numerals that reveal the outline of sections and subsections and renum-bered the five footnotes serially, making them endnotes.

An eloquent defense of the institutionalization of “the rational will” in the state, it comple-ments nicely, I think, Lonergan’s meditation on cosmopolis. On the presupposition that God has revealed His will, however, I prefer the problem of discerning it and comparing-contrasting it with our individual wills to the problems that attend treating the state as the realization of either Lonergan’s or Blanshard’s abstractions.

Anthony Flood

October 7, 2013

The Rational Will

Brand Blanshard

In the end, then, every political right must be defended on moral grounds. But we cannot leave the matter there. For moral and political rights are not simply identical; there are many moral rights that no one would call political, for example, the right to be spoken to courteously and the right of parents to the consideration of their children. Political rights are rights that are, or appropriately may be, guaranteed by government, that is, by enforced law. Now it is clear that there are “rights” thus enforced by law for which many who must heed them can find no moral justification at all. But now for the real difficulty. The state claims the right, for example, and enforces it by heavy penalties, to reach down into the pockets of its citizens and take a large part of their income for its own purposes. Many of these citizens are convinced not only that the particular purposes for which the state will use this money are bad, but also that an income tax as such is a policy opposed to the general good. To tell these people that what they regard as a wicked tax imposed for wicked purposes is a moral right, on all fours with the right to truthful speech and civil treatment, is not unlikely to provoke jeers. Clearly there is a missing link in the argument. These people are told that it is a moral obligation to do what produces the greatest good. They believe that a law passed by their government is inimical to the public good, and are told that they should obey it nevertheless. That may be a political obligation, but to call it a moral obligation looks very much like self-contradiction. How is one to make out that it is their moral duty to obey a law that they disapprove? This is probably the most searching question in political theory.

I believe that the true answer to this question has been given by philosophers over and over again, and that it is not the exclusive property of any school. But it has had a history so unfortunate as to rob it of much of its persua-siveness. It was suggested by Rousseau, but, as presented by him, was so embedded in mythology and bad argument that one can extract it only with difficulty from his incoherent text. It was stated again by Hegel, but was made an integral part of a system of logic and metaphysics which most philosophers have found it impossible to accept; besides, it came to be associated, partly by his own fault and partly not, with Prussian nationalism, which after precipitating two wars, earned general detestation. The doctrine was taken over from Hegel by the British idealists and given a more judicious statement by T. H. Green, whose Principles of Political Obligation remains, I think, the weightiest work in English on political theory. It was presented again by Bosanquet in The Philosophical Theory of the State, but with needless obscurity and with certain expressions that sounded suspiciously like endorsements of absolutism and nationalism. These were seized upon by L. T. Hobhouse in his Metaphysical Theory of the State and made the focal points of the most thorough-going attack that has been made on the theory.

Rousseau called his version a theory of the “general will”; Hegel and Bosanquet talked, instead, of the “real will”; if the version about to be presented is to have a name, I should prefer the “rational will.” It may be of interest to say that my own conviction of the truth of the theory came through reading Hobhouse’s attack on it. It had been so long out of favour and was mentioned with such general deprecation that, having made no careful study of it, I had come to think of it as pretty certainly indefensible. Its association with the name of Hegel, and the many attempts to link Hegelianism with Fascism did not help, though I follow Principal Knox in holding that the occasional outbursts of Prussianism in Hegel are excrescences on his system, and not organic to it. When I ap-proached the doctrine of the real will, I began by reading the critics of the theory, expecting at least to find some amusement in watching the work of demolition, and thinking I should be more likely to find intelligibility among the critics than among the exponents. The first two or three broadsides I reviewed left me in mild surprise, for the target was still visibly standing when the roar had subsided and the smoke cleared away. But these were guns of low calibre. So I turned to Hobhouse, who had, I understood, destroyed the theory utterly; and as I warmly admire his work, I sat down to him expectantly. But as the arguments in the heralded parade limped slowly past, a conviction gradually formed itself in my mind. If this was really the best that could be said against the theory of the real will, I had been deceived about it. Wave after wave of argument broke against it only to leave it, so far as I could see, standing aggressively intact. By the time I was half way through the book, I had begun to think the case for it impregnable; at the end, my conversion was complete. I thought then, and have never wavered in thinking since, that this doctrine, if one penetrates through the sorry form in which it has so often been expressed, and gets rid of associations that cling to it like barnacles, offers the firmest available core for political theory.

The doctrine is quite simple. It is that men have a common moral end which is the object of their rational will, that the state is a contrivance that they have worked out to help them realize that end, and that its authority over them rests on its being necessary for that end. If it is politically obligatory at times to obey a law that one regards as bad, that is because the state could not be run at all if the citizens could pick and choose which laws they would obey. Ultimately, therefore, political obligation, even that of obeying a morally bad law, is a moral obligation; and when, as occasionally happens, it becomes a duty to disobey, the ground is still the same. I believe that this simple doctrine is what all the philosophers who have defended a “real” or “general” will, from Rousseau to Bosanquet and even Hobhouse himself, have in fact been arguing for. I shall not try to prove this by historical inquiry, for my prime concern is not whether the doctrine I seem to find in them is actually theirs, but whether it is true. The doctrine that does seem to me true may be expanded and made more explicit in four propositions: First, we can distinguish within our own minds between the end of our actual or immediate will, and the end of our rational will, which is what on reflection would commend itself as the greatest good. Secondly, this rational end is the same for all men. Thirdly, this end, because a common end, is the basis of our rights against each other. Fourthly, the justification of the state, and its true office, lies in furthering the realization of this end. Let us try to get these points clear.

It is puzzling at first to hear of a real or rational will which can be set over against our actual will. Is not our actual will our only will, and whatever goes beyond this, myth? On the contrary, it is easy to see that what we have here is a distinction of the first importance. A man goes to a dealer and buys a motor-car. There is no dispute about his actual will; it is simply to possess the car; that is what he immediately and unmistakably wants. Is there any sense in saying that he has a further and rational will that goes beyond this and might even veto it? Yes, undoubtedly; in fact, unless we concede such a will we shall never understand what really moves him. If possessing the car were an ultimate end, the question “Why buy it?” would be meaningless. But the buyer would be the first to insist that it was anything but meaningless, and if he were like other eager buyers he would readily explain that the car was a means to all sorts of advantages, personal, professional, and social, and these, perhaps, means to still further advantages to a widening circle of beneficiaries. In short, he wills to buy the car, but he wills it subject to tacit conditions as to how it will contribute to an end beyond itself. The evidence that these conditions exist lies in what would dissuade him from the purchase. Convince him that through buying the car he will not advance his business, that his son and daughter being what they are, it will probably involve them in accidents, and that if he carries the purchase through, he cannot move into the larger house that is the family’s most pressing need, and he will not improbably cut the whole business short. If his actual will were self-contained, if it were the end of the line rather than a link in a chain whose point of attachment lies far beyond it, all this would be irrelevant. It is only because his explicit will is not exhaustive, because its object is a means to a further end, or a piece in a larger picture which is more fervently wanted than itself, that his immediate will can admit such correction. He may hardly have known that he wanted these ulterior things; at the moment of buying he was probably not thinking of them; but if, the instant he sees how his will of the moment bears on them, he sets that will aside, is it not natural to say that in contrast to the objects of his actual will, they are the objects of his real or rational will?

This line of reasoning, we may be told, leads to an unplausible consequence. For if his present will is thus open to correction by ulterior considerations of advantage to himself and his family, these considerations themselves will in turn be open to correction by still further con-siderations, for example, his duty to his pro-fession, his community, and his country. “What you are saying, then, is that the object of a man’s real or rational will is that which an ideally competent reflection would show to be the greatest good attainable in the circum-stances. No doubt with ideal powers this is what he ought to will. But you are saying that he does in fact will what he ideally ought to will, and that is absurd.”

I do not think it is. To be sure, one may easily enough prove it absurd if one takes the two wills on the same level of explicitness. If to will something must mean to will it immediately and with full awareness, then the suggestion that we always will what it would be best to will is absurd. Very well then; out with the word “will”; we are not insisting on words; we are insisting on what we take to be a fact, and one of the prime facts of the moral life. Writers describe it variously. The theologian would say that at our best we remain miserable sinners; the moralist that we never do our whole duty; the poet that “what I sought to be, and was not, comforts me.” However capricious or selfish or brutal a man may be in actual behaviour, if we are right in calling him a moral being at all, what he is trying to be and do is never exhausted in what he is. Whenever he makes a judgment of better or worse, whenever he does anything because he thinks he ought to do it, even when he thinks this without doing it, he is recognizing a claim as prior to the wants of the moment and conceding it the right to overrule them. A man may flout this claim to any extent in practice, and protest that he neither recognizes it nor tries to fulfil it. Is his protest to be accepted? Surely not. We could point, if we knew him well enough, to a thousand actions that belie his own report. He continually defers present good to a later and greater good, corrects impulsive choices by reflection, recognizes the force of another’s claim when at the moment he would prefer not to. In doing so, he concedes the claim of a rational good upon him, a claim which, if he is consistent, he must admit to have overwhelming force in confirmation or in veto of the will of the moment. We agree that he does know in detail the object of this larger will. We agree that it is not a will at all in the simple straightforward sense in which the will of the moment is such. But it remains a will in the extremely important sense of an ideal to which the man by implication commits himself every day of his life and whose claims he cannot repudiate without turning his back upon himself.

If this is true, the distinction must be accepted between a man’s actual will and his ulterior will, his real or rational will. That was our first point. The others may be dealt with more briefly.

The second was that the end or object of the rational will is the same in everyone. This looks questionable. But the fact is that we could not even argue with each other with any point unless it were true. Consider the matter first on the side of theory. When we argue, we both assume that there is a truth to be found, that its discovery is our common end, and that there is a standard way of gaining it. If we differ as to whether President Madison preceded or followed President Monroe, we have no doubt that one did precede the other, or that if the evidence is rightly assessed, it will point one way. If this were really in doubt, there would be no sense in arguing at all. What would be the use of your trying to convince me if what was proof to you was in the end mere fallacy to me? The very essence of your attempt to show me my mistake lies in appealing to our common end, namely to grasp what fact and logic require, and if you can show that in this respect or that I have fallen short of these re-quirements, you expect me to see and acknowledge my error. Unless our thinking is governed by the same ideal, unless what would ultimately satisfy you as cogent evidence or conclusive proof is assumed to be the same as what would satisfy me, argument is a waste of time. So long as we do make that assumption, there is hope. Argument is the joint appeal to a fundamental agreement in the hope of extending it to remove a relatively superficial disagreement.

The same holds on the practical side. Men expostulate with each other over wrongdoing just as they argue over fact. Now when another expostulates with me over an action that seems to him wrong, what sort of argument must he use if he is to convince me? He must show me that the action I am considering will not, as I suppose, subserve the sort of ends that we approve in common. Suppose he finds me set on buying the motorcar, and thinks it a mad-cap scheme; his argument will take essentially the following form: “You think it of the first importance, don’t you, that one’s family should be comfortably and healthfully housed?” “Yes.” “Well, if you buy the car, you must sacrifice that end for occasional pleasures that you admit yourself to be less important.” That is, he appeals to an end about which he feels confident that I agree with him, and tries to show me that the action I am proposing would defeat it rather than promote it. If I were to betray to him that I had no interest whatever in the welfare of my family, he would be at a loss how to proceed, for his argument assumes that I attach the same value to this that other sane men do. Put in the abstract, what he is saying is: “You agree with me that E is the important thing at stake; if you do M you will jeopardize it; if you do N you will get it; therefore you should do N.” Unless there is some broad agreement on the ends that are worth pursuing, neither of us would have any purchase on the thought of the other.

There is, to be sure, an element of paradox in this view. If the Russians get involved with the Americans in an argument over practical politics, does it really make sense to say that they are both driving at the same ultimate end? Yes, I think it does, and thinking so increases my hope in the work of an international forum where they may meet and canvass their differences. Indeed, considering the bitterness of their differences, their professed ends are surprisingly near to identity. The Russians insist that they believe as strongly as the “demo-cracies” in the dissemination of knowledge, in freedom for the masses of the people, in the cultivation of literature and the arts, and in the increase through applied knowledge of the comfort, health, and happiness of mankind. Their difference with the west is not in our accepting and their rejecting these goods, for both parties avow devotion to them; the difference is that whereas the communists think that capitalism is an atrociously bad means to these ends and communism an exceedingly good one, the west thinks that communism is a bungling and tyrannous means to them and a “free economy” a more effective one. The United Nations has been treated to many strange scenes and strange arguments, but it has not yet, I think, been invited to listen to a plea for ignorance, misery, and slavery as the true ends of man. Since all alike accept certain ends, they can argue with some point about the means. If the Russians were seeking ends that really had nothing in common with ours, if they were aiming, for example, at unhappiness in widest commonalty spread, discussion with them would take a remarkable form; when we offered an argument to show that a Russian move was calculated to increase human misery, we should be greeted at the end with applause and the exclamation, “Bravo; you put our case admirably.” It is happily to be doubted whether among sane and candid men this ultimate difference about ends ever occurs.

The third proposition is that our rights against each other are based on our common ends. Smith borrows money from Jones, and when the debt falls due, Jones claims the right to repayment. On what ground? Not, surely, on the ground alone that it furthers his own interest, since that might not be Smith’s, nor on the ground alone that it is Smith’s interest; to say that would too often be hypocritical and false. To get the key, we must ask another question, Is Jones’s right to be repaid the same as Smith’s duty to pay? We have seen that in substance it is, since a duty is the obverse side of a right. When Jones presses his claim against Smith, he is therefore insisting on Smith’s duty to repay. Why is it Smith’s duty to repay? Duty, as we have seen, is always based on the production of good. What is the good in this case? It is not merely Jones’s satisfaction in getting his money back, though that will form part of the end for any considerate debtor. It is also the maintenance in society of a state of things in which promises are kept and debts repaid. When Jones presses his claim against Smith, he is saying in effect, “You believe, do you not, as I do, that this state of things is better than one in which promises are broken and debts repudiated? Very well, if you do, your only consistent course is to pay.” That this common end is the basis on which Jones is urging his right may be clearly seen by his helplessness if Smith rejects it. Suppose Smith rejoins, “I see no value whatever in a state of things in which promises may be relied on or debts repaid; this may be an end or good for you; it is not for me.” What could Jones do? He could threaten him with the police, but that is not argument, and no argument he could offer would carry the least validity for Smith. To urge that Smith seek a good which for him was no good at all would be absurd. Jones’s case in its entirety rests on the assumption that he and Smith are seeking a common end, and that when the repayment of the debt is seen to be required by that end, Smith will recognize it as his duty and do it. But that he should so recognize and do it is precisely what Jones is claiming as his right. To put it generally, your right against me and my duty to you rest on an identical ground, namely their necessity to our joint end.

Now for the fourth proposition: it is because the state is the greatest of instruments to this common end that it has such rights as it possesses over its citizens. The state is more than a system of rights. If half a dozen hunters met by accident in the woods, such rights would hold among them, but this could not make them into a state. A state is a set of institutions—a legislature, courts, police, a chief executive—designed to give effect to these rights, to guarantee them in practice. The state is thus a means, not an end. It is a system of brakes and prods applied in the interest of reaching a goal beyond itself.

The simplest evidence for this lies in the answer we naturally give to two related questions, Why should I obey the law? and Why may I sometimes resist it? The answers to both are the same, and they amount to an admission that the state is an attempt at the embodiment of a common rational will, and is justified only as the instrument of that will. Why should I obey the law by doing anything so disagreeable as paying my income tax? Not because I have to, since with enough cleverness I might evade it, nor because I can point to any definite advantages to me or anyone else that would result from this particular act. I should obey it if at all because it belongs to a system of commands and restraints whose maintenance serves better than any available alternative as an instrument for the common good.

It is needless to work this out in detail. Everyone knows that a government is often a nuisance, whose rules about parking cars, stopping at street lights, paying taxes, keeping walks clear, and all the rest, are a source of endless major and minor frustrations. We all believe, nevertheless, that though government is a nuisance, it is a wholly indispensable nuisance. Why? Because without it the main goods of life, and for that matter life itself, would be insecure. If we can count on our house and its contents not being taken away from us, if the shops that supply our clothes and fuel and food are able to do their business, if there are roads on which we can get about, schools to send our children to, courts and police to deal with those who would take advantage of us, it is because behind these arrangements, protecting and guaranteeing them, is the power of the state. Without it we should be at the mercy of the worst elements in our society. We may concede to communists and anarchists that if the ends men are seeking in common could be realized without the com-plex and expensive machinery of government, it should be dispensed with. We cannot agree with them in supposing that, human nature being what it is, there is any prospect whatever of attaining these goods except with the aid of the state.

Does it follow that since the state is a necessary means to our major ends, we should in all circumstances obey it, that we never have the right to rebel? Not at all. Our view would not only justify disobedience in some cases; it would require it. If the state is regarded, not as sacrosanct or an end in itself, but as an instru-ment to certain great ends, then when it be-comes so corrupt as to cut us off from those ends rather than further them, when it serves its purpose so badly that it is better to risk chaos for the sake of a better order than continue to suffer under the old, then resistance becomes a right and a duty. This will be an extreme and desperate case, since it will obviously be better as a rule to obey what we regard as a bad law and try by persuasion to get it amended than to seek the overthrow of the power which supports all laws alike. But there is no doubt that when government has ceased to serve its major ends, the people who have fashioned it to serve those ends have a right to replace it with something that serves these better. In doing so, they will appeal to the same ends that earlier led them to support it, and they will do so with full consistency and justification. Thus the theory of a rational will provides a natural and intelligible ground both for obedience in normal cases and for disobedience in abnormal cases. It is hard to conceive what better evidence could be offered for it.

Here then is a theory of political obligation. It holds that each of us is seeking an end that goes beyond the good of the moment, that besides his will of the moment for food, drink, and comfort, he has a rational will directed far beyond these to what would satisfy in the light of a fully critical reflection. The nature of that end we have explored in earlier chapters. At best it is conceived vaguely and pursued waveringly, but its presence nevertheless is both the magnet that draws us on and the monitor that reproves when we stray out of the way. This end, we have held, is the end of all men. Because it is, each can justly claim of another that he should be loyal to it; that is what we mean by a right. The state itself is an arrangement accepted as a necessary means to this ultimate end, and on this necessity rests its right to obedience.

This account of political obligation seems to me at once simple and compelling. There is probably nothing novel about it. Indeed I have suggested that it was what all the defenders of a real and general will, from Rousseau to Bosanquet, were in substance contending for. Rousseau maintained that in all men there is a will toward the same moral end, that government is a device set up by that will through a contract or agreement, that this will, as a striving for the good is, by definition, never wrong, though even the “will of all” may mistake what it really requires, and that its requirements, even as to the structure of government, may vary greatly with circum-stances. In these contentions I think Rousseau was right. Unfortunately this core of sound teaching was embedded in a mass of myths and mistakes that were as adventitious to it as moss to a stone. Rousseau dimmed and confused a remarkable insight when he held that men are animated by self-interest only, that the general will is aimed at a queer, scarcely thinkable abstraction in which their selfish wills coincide, and that the government can impose no burden and confer no advantage except upon all alike. Indeed his doctrine as presented is so incoherent that all one can hope to derive from it is a general drift—a drift in the right direction nevertheless.

Something similar must be said of Hegel. His insistence that an identical and rational end was working itself out through individual minds, that every society showed in its laws and customs the working of this will, and embodied it in differing degrees, all this and much else that this astonishing intelligence had to say about politics is true. Unfortunately he put himself in the wrong with all manner of persons who would otherwise have been disposed to listen by talking gratuitious nonsense about the state as der Gang Gottes in der Welt, holding that the success of a state in dominating others was somehow evidence of its right to do so, arguing that the relations of states cannot be judged by moral standards, and suggesting that the state is not only an attempt to embody reason, but, in the case of the dominant state of the time, does embody it so fully that the citizen will achieve his highest morality by conforming to it and will have no case if he resists it. How far such doctrines belong to the essence of Hegel’s political theory is a matter of dispute; I am myself inclined to think that they are extraneous to it.1 But he cannot be acquitted of having said things that gave apparent benediction to totalitarian violence and oppression, and anyone holding a doctrine akin to his must be at pains to show that the charges heaped upon it do not apply to his own. That the inspiration common to the contract theories and to the Hegelians is really innocent of these charges can be shown easily enough. It will pay us to look briefly at the worst of the accusations.

The theory, it is said, would not only justify but glorify wrong. If the state is the instrument of the general will, and the general will is a will to the moral end itself, what embodies this will must be right. Hence whatever the state does, however tyrannous and brutal, is to receive our benediction. Each of us is supposed to realize, Hobhouse says,

That in society he is in the pre-sence of a being infinitely higher than himself, contemplating a rea-son much more exalted than his own. His business is not to endea-vour to remodel society, but to think how wonderfully good and rational is the social life he knows, with its Pharisees and publicans, its gin-palaces, its millions of young men led out to the slaughter, and he is to give thanks daily. . . . . [Such a doctrine] instead of seeking to realize the ideal, idealizes the real.2

Harold Laski wrote in similar vein:

For him [Bosanquet] the good is always being realized. The subserving of our real will with the will of the state is taken to mean that the best that can happen to us is in fact happening at each mo-ment.3

Now if the doctrine of the rational will is examined, not in the light of occasional foolish phrases, but in the light of its essential drift, one can see that not only does the above inference fail to follow; the only legitimate inference is quite the opposite.

The real will goes beyond the actual will; it does so everywhere and always. That is the point of the contrast between them. The good that would completely satisfy me is never achieved in this act or that. To recognize the real will is to arouse discontent with what is, to indict the good I have actually achieved in the light of what might be. To say, in the individual case, that the recognition of the real will meant somehow glorifying the actual would be so patently contrary to the point of the distinction as to wear its falsity on its face. How is the case different when we turn to the will of a community? The recognition of a real will is the recognition that there is a greatest good for that community and that it is the business of the citizens to regulate their communal life so that this good may be as fully embodied as possible. The very insistence on the distinction implies that it is not so embodied now. To be sure, the doctrine implies that one is ordinarily to obey the law, but, as we have seen, one cannot so much as state the reason for that obedience without acknowledging an authority above the law, which we may invoke against the law itself if that should fail.

The second charge against the theory is that it would give the state a power over the individual which is complete and beyond appeal. If he dares to call it in question, he is told that the maintenance of this state and its laws is what his real will desires, and that if he appeals from Philip drunk to Philip sober within himself, he will see that he has no case. To some critics of the general will, this is the least pardonable part of the doctrine. Mr Laski thinks it absurd to say that

constraint is not the use of force by the state against the individual, but only its imposition upon him of the will which his real will desires. . . . Most of us, I think, would argue that the revolutionist is never conscious that the government which imprisons him is giving his true self freedom. What he experiences is constraint; and he regards that as a denial of his liberty. To tell him that he is made free when he is prevented from fulfilling the purpose he regards as the raison d’etre of his existence is, I would suggest, to deprive words of all their meaning.4

The climax of absurdity is thought to be reached when the theory touches punishment. It is bad enough to say, when a law is passed which we tried to prevent, that the law is what we really wanted, and to compel us on this ground to obey it; but it is one degree worse to tell us, when we have been put in jail for resisting it, that we were really hungering and thirsting for incarceration at hard labour. To take this line is to cut from under our feet any ground to stand on in protest; it is to reduce us to the level of children who are to be told by persons wiser than they what is good for them and what is not. And it is to outlaw resistance to tyranny as the manifestation of wayward self-will.

Most of us would agree with the temper of this remonstrance; at least I should myself. For anyone, however high in authority to presume to tell others over their protests what is good for them is a repellent and dangerous business. But there are several things to be said about it.

First, the problem here involved is not peculiar to the theory advocated; it confronts every theory and form of government that is worth considering. It is the business of government as such to find and promote the good of its people. But there are nearly always persons, sincere and high-minded persons, who believe that what the government proposes is neither for their own good nor anyone else’s, and who are prepared to resist its mandates. In such cases, what is the government to do? It has commonly put coercion upon them in the interest of the many. It is not easy to see any alternative. If this leads to tragedy, it may be inevitable tragedy; indeed, as Hegel pointed out regarding Socrates, it is tragic because so inevitable.

Secondly, is such coercion necessarily tyranny? The theory of the general will regards government as an instrument to the common end of the greatest good. Can the citizens instruct their government in detail as to what this good consists in? Not if Burke’s famous speech to the electors at Bristol is sound, and on this point it is hardly questionable. Government is not, or not merely, for the execution of mandates given; it is largely for the discovery of what mandates ought to be given. Now if a citizen wants a government, if he approves on the whole the method by which it gained power, if he has commissioned it to ascertain and promote as best it can the community’s good, then in a quite intelligible sense its decisions are his decisions. He has willed that it should make them for him.

What if one of these decisions conflicts with a preference of his own? Can it reasonably be said that his real will is here conflicting with his actual or particular will, and that he himself is willing that this particular will should be set aside? Mr Laski thought this absurd.

The Nonconformist who paid his education rate under the Act of 1902 did not do so because his real will approved of the Act. He did so because he took the view that, on balance, it was better to put up with one bad law than to challenge the authority from which all laws derive.5

This assents to our view in substance while rejecting it in words. The Nonconformist preferred, we are told, to keep the government in existence, even though it thwarted some of his desires, because he thought that better on balance. We accept this account and are proposing to call this preference his real will. Mr Laski thinks that so naming it is confusing. I do not see where the confusion lies. It is admitted on both sides that the Nonconformist wants the law not to be. It is admitted on both sides that he wants still more that the instrument which made the law should remain in being, in spite of its cost to himself. Where is the confusion in saying that what he admittedly wants most is his real will? We are not denying any facts or taking illicit advantage of him in saying this. We are not denying that he dislikes the law. We are proposing that theory should stay true to fact in noting that his desires are not of equal strength or importance. If he wills the machinery of government at the well-known cost of occasional thwartings of his and others’ wishes, there is, or need be, no confusion in saying that it is his real will that these thwartings should be imposed.

Even the ridicule about punishment does not stand up very well under scrutiny. It rests again upon putting all facts on the same level. When a motor policeman holds me up for careless driving, it is superficially absurd to say that I want to be held up and fined. But is this more than superficial? What citizen who takes his citizenship seriously has not in his heart, however colourful his actual language, given the policeman full marks for doing just what he did? Nobody wants to be held up when in a hurry; nobody wants to get a “ticket”; but men have been known to go away thankful that an agency of theirs is so impartially on the alert in serving the interest of the community. In such cases, would the critics say that it is absurd and contrary to fact to be thankful that one’s will has been frustrated? But the “absurd” fact does occur.

Thirdly, while regarding government as the instrument of the general will is admittedly dangerous, it is less dangerous than its alternatives. Any conception of government will give grounds for injustice if used insincerely; but sincerity assumed, it is hard to conceive a criterion of governmental behaviour less likely to lead to oppression than reference to what the citizens genuinely want. It rules out ab initio all abuses based on power, and all government in the interest of a single man or class. The will which is to be expressed and to which government is responsible is conceived as working in every citizen and hence entitling him to be considered; and the content of that will can be ascertained only by remaining close to its source.

Fourthly, we repeat that if in the attempts to determine and achieve the common end a government blunders into cruelty, it is absurd to lay this cruelty at the door of the theory itself. As well interdict the aim to be rational, with the schools that subserve this aim, because if we pursue it we stumble at times into fallacy, as decry the pursuit through government of a common good because men at times misconstrue its demands. No other theory of government would bow to such criticism, and neither need this. Suffice it to say that in any state whose members take this high pursuit seriously there will be a constant pressure toward legal and social amendment. Men who believe in a common end and a common reason will naturally seek to make them prevail; and that such prevalence would transform society needs no arguing.

Notes

1 For a discussion of the rights and wrongs of this issue, see the papers by T. M. Knox, E. F. Carritt, and others in Philosophy, Vol. XV (1940), pp. 51-63, 190-6, 219-20, 313-7.

2 Metaphysical Theory of the State, 87, 112.

3 Aristotelian Society Proc., 1928, 56. C. E. M. Joad took a similar line in his Guide to the Philosophy of Morals and Politics, 598.

4 The State in Theory and Practice, 59—60.

5 The State in Theory and Practice, 59.