AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

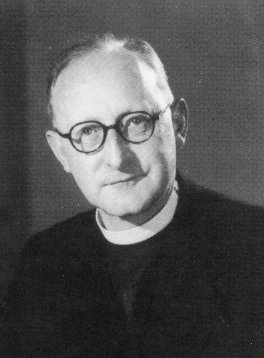

E. L. Mascall

1905-1993

John B. Cobb, Jr. [Wikipedia entry]

The text of Chapter 2 of Living Options in Protestant Theology, Westminster Press, Philadelphia, 1972, reformatted from text found here.

Posted May 21, 2011

The Thomism of E. L. Mascall

John B. Cobb, Jr.,

When we think of natural theology, we think first and foremost of Thomism. Natural theology existed before the time of Thomas, and many new forms have appeared since his time, but it was he who gave classic statement both to the relation of natural theology to Christian revelation and also to the content of natural theology itself. The semiofficial adoption of his basic formulations by the Roman Catholic Church has guaranteed a historical importance to his work that is commensurate with its intrinsic interest.

Our own century has witnessed a revival of Thomism that has had great influence even beyond the bounds of the Roman Catholic Church. For many Protestants, as well as Roman Catholics, much of Thomasí position appears to be viable despite the lapse of centuries since its formulation. Hence, even though this book limits itself to Protestant theology, it is fitting that it begin with a serious discussion of Thomism.

Unfortunately, despite the very real respect with which many Protestants regard contemporary Thomism, they have left its exposition and development largely in the hands of Roman Catholics. The names of Etienne Gilson, Jacques Maritain, R. Garrigou-Lagrange, and E. Przywara come readily to mind, but as Roman Catholics they are not available for use here. However, E. L. Mascall, a contemporary Anglican theologian, drawing heavily upon the writings especially of the French Thomists (E. L. Mascall, He Who is: A Study in Traditional Theism, p. x.), has done impressive work in interpreting and developing Thomism in a non-Roman Catholic context.

Even Mascall can be called a Protestant only by the very loosest use of the term. He thinks of himself as a Catholic, and the detailed formulation of his theology gives clear expression to this fact. In the following exposition, predominant attention will be given to his natural theology which, as such, would be quite compatible with non-Catholic doctrines. Mascallís Catholic theological position, which presupposes an understanding of the church alien to Protestantism generally, is barely sketched. His extensive discussions of the liturgy, orders, and sacraments of the church are almost wholly neglected.

For these aspects of Mascallís work, see especially Corpus Christi; The Recovery 0f Unity; and Christ, the Christian and the Church, Chs. 9 to 11.

Contemporary Thomists are not concerned with slavishly reproducing the ideas of Thomas Aquinas. They recognize that much of what he said was conditioned by the naÔve science of his day and by his excessive commitment to Aristotelian philosophy. (E. L. Mascall, Existence and Analogy, pp. xvii, 73, 77, 84-85.) But they do believe that the basic principles and structure of his system provide the basis for solving both the philosophical and the theological problems of our own time. It will not be our concern in this chapter to judge whether Thomas in fact intended all the ideas that Mascall and other Thomists derive from him. Our concern will be only to formulate these ideas as clearly as possible in a brief compass and to evaluate the adequacy of the evidence to which appeal is made for the conclusions that are drawn from it.

It is sometimes supposed that natural theology intends to embody only those ideas upon which all reasonable men in fact agree. Since today there are no ideas of religious importance upon which such agreement can be claimed, there clearly could be no natural theology in this sense. Since this is self-evident, we may assume that the practitioners of natural theology do not claim universal acceptance for their views. On the other hand, if they affirmed only that their natural theologies constitute one among a plurality of equally rational systems of thought, they would be left with a relativism that would be alien to the concept of natural theology.

Mascall is fully aware of this difficulty, but he does not think that it destroys the case for natural theology in its traditional Christian form. The argument is not that all men capable of rationality reach the same conclusions but that those who are willing to be attentive to the right data and open to the correct interpretation can be led to see that certain conclusions follow necessarily. (Ibid., p. 75) The obstacles to the acceptance of traditional natural theology are indifference, habit, prejudice, blindness, and laziness. (Ibid., p. 90.) Our whole urban way of life with its artificiality and emphasis on distractions militates against the kind of concern, sensitivity, and patience that is required for natural theology. Hence, it is not surprising that the arguments of natural theology seem strange and irrelevant to many moderns. But it is clear also that this understandable response does not imply the falsity or in-adequacy of the doctrines themselves. (He Who Is, pp. 80-81.)

The foregoing might seem to suggest that natural theology could be found adequately developed among pre-Christian thinkers who devoted themselves with requisite patience and concern to the discovery of ultimate truth. But history shows us that this is not the case. Does this not invalidate the claim of natural theology to be the reasoned knowledge of God that is systematically independent of revelation?

Again Mascall is fully aware of the problem. Indeed, he places considerable emphasis upon the difference between the philosophy of the Greeks and the natural theology of the Scholastics. (Existence and Analogy, pp. 1-10, 15-17.) He recognizes the role of revelation in making possible the achievement of this natural theology. He does not claim, therefore, that natural theology was factually possible apart from revelation. (Ibid., p. 11.) He does claim that the ideas and arguments developed in Christian natural theology are intelligible to those who do not accept the claims of revelation and that if they are sufficiently open and interested they can be led to see the decisive cogency of the reason that is employed. Presumably one might compare the situation with that which occurs with respect to a new discovery in mathematics. It is not factually the case that reasonable men acknowledged this truth prior to the time of its discovery. It is not factually the case that all reasonable men acknowledge it after its discovery. Nevertheless, what has been discovered is in principle rational, and those who have sufficient patience and interest can be shown that this is so.

In this way Mascall clears away the most obvious objections to natural theology as such. The factual relativism and historical conditionedness of every systematic position, he argues, do not imply the systematic relativism of every position. The systematic claims of a philosophical argument must be taken at face value and judged on the basis of rational examination. If this is done, Mascall believes, the traditional Christian natural theology that is given classical expression by Thomas Aquinas can be shown to be true.

In our time, the objections to natural theology have come not only from philosophers but also from theologians. These have argued that our attempts to gain an understanding of God by reason is a betrayal of the God who has revealed himself to us. The God of reason is an idol of the mind and not the living God of revelation. Faith is not faith unless it is a leap beyond all reason and all calculations of probability. (He Who Is p.76.)

Once again Mascall is quite aware of this attack by Protestant theologians upon the enterprise that he advocates. He agrees that there is a real difference between the philosophic apprehension of God and the understanding of God given in revelation and worship, and that the former is poor and barren beside the latter. (Ibid., p. 81) But he is quite sure that the God who is apprehended in these two different ways is the same God. We cannot meaningfully affirm that Christ is the incarnation or revelation of God unless we can explain what we mean by God (Ibid., p.2.), and although the most valuable part of our knowledge of God comes from the revelation in Jesus Christ, that part which reason provides is a necessary basis on which the rest can be built. (Ibid., p.24.) The value of faith stems not from the irrationality of its object but from the humility that is required to see the truth which is accepted, and the courage required to act upon it. (Ibid., p.77.)

Of course, it is not necessary for each individual to study natural theology before he is prepared to accept revelation. Those who grow up in the Christian church normally follow no such order. But we must be concerned also for those whose thought is not formed in a Christian environment and who quite reasonably ask what faith is all about. To them we must be prepared to explain what we mean by God and to show that he exists, in order that they may be prepared to consider seriously the claim that he is revealed in Jesus Christ. (Ibid., p.26-27.)

What has just been said indicates that special revelation cannot constitute the sole basis of our knowledge of God. Unless our total understanding includes belief in something that can reveal itself, we cannot apprehend any occurrence as a revelation. Revelation reveals more about that which is already known to be. Faith cannot dispense with this prior knowledge.

For this reason there are only two real alternatives to natural theology as a basis for Christian faith and theology. One might affirm that the required general knowledge of God is given in religious experience, that is, in direct consciousness of him. (Ibid., p.16.) One might also affirm that Godís existence is strictly self-evident, so that no reasoning is required to arrive at this knowledge. (Ibid., p.30.) Mascall considers both these alternatives to show their inadequacies.

Many Protestants reject the view that God is known by argument or inference in favor of the view that he is immediately experienced. Apart from such experience, they suppose, argument is unconvincing. With this experience, argument is unnecessary.

Mascall does not deny that there is such a thing as authentic, immediate experience of God, but he does deny that this is the normal or general basis for believing in God. By far the larger part of the experiences to which men appeal can be explained from a psychological viewpoint without recourse to the hypothesis of Godís reality. (Ibid., p. 17ff.) Only the greatest mystics have attained that purer experience which radically transcends these natural categories. Even with respect to them, we must acknowledge a diversity of interpretation as to the immediateness of their awareness of God in himself,

Ibid., p.21. See also his discussion of mysticism in Words and Images: A Study in Theological Discourse, pp. 42-45.

and these interpretations will depend in part upon some other knowledge of God than that given in the experience itself. Mascall, therefore, does not disparage religious experience, but he emphatically insists that it cannot become a substitute for natural theology. (He Who Is, p.29.)

Some who acknowledge the inadequacy of both revelation and religious experience as bases for belief in God affirm that Godís existence is self-evident. The classical formulation of this position is the ontological argument of Anselm of Canterbury. According to Anselm, the concept of God implies his existence. This is because the concept of God is the concept of that than which nothing greater can be thought, and lack of existence would contradict this concept.

Ibid., p.31. For further discussion of essence and existence, see Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, pp. 29-45.

Mascall agrees that in the sphere of being, the essence of God is unique in that it includes his existence. Thus Anselmís argument may be accepted as showing that if God exists, his existence is necessary. But the fact that Godís essence includes his existence does not imply that our concept of God implies his existence. Our concept of Godís essence only proves that we cannot form a concept of God that does not include the idea of his existence. But the idea of Godís existence is not the same as his actual existence. (Mascall, He Who Is, p. 34.)

Having cleared away the objections to the enterprise of natural theology and having shown that we cannot regard its conclusions as self-evident, we must turn to the enterprise itself. Its heart and core consists in displaying the rational necessity of acknowledging the existence of God and the implications that are given in this argument with respect to Godís nature.

Thomas Aquinas developed five arguments for the existence of God. The first argument, and that upon which he relied most heavily, is the familiar argument from motion or change. Change is understood in Aristotelian terms as the actualization of a potentiality. This actualization requires an explanation in terms of a cause that cannot lie either in the potentiality as such or in that which is actualized. Hence, change points to a cause beyond that which changes. This cause may be some other changing entity, but we cannot conceive of this succession of causes as infinite. Hence, a cause must be acknowledged that causes change without itself changing. This cause is God. (Ibid., pp. 40-45.)

The second argument is that not only change but the being or preservation of entities requires causal explanation. Once again the being of one entity may be explained by the act of another, but an infinite series cannot be admitted. Hence, a first cause of being must be affirmed. (Ibid., pp. 45-46.)

The third argument is based on the categories of contingency and necessity. The fact that the entities we encounter around us are subject to generation and decay indicates that they are contingent, that is, that they are capable of not being. But if there had ever been a time when nothing existed, then nothing could ever have come to exist. Hence, it is necessary that there be something that is not contingent, therefore, necessary. This necessary being either has its necessity in itself or receives it from another necessary being. To avoid an infinite regress we must affirm a being that is the cause of its own necessity. (Ibid., pp. 46-49.)

The fourth argument is from the degrees of excellence perceptible in things. These degrees of excellence can be understood only as degrees of approximation to an absolute norm by which they are judged. One thing is better than another if it more nearly approaches that which is ideally good in itself. Hence, the presence of degrees of excellence in things demands as its cause that which is perfect in itself, namely, God. (Ibid., pp. 52-54.)

The fifth and final argument is that from purpose. Just as every entity requires an explanation of its being in terms of an efficient cause of being (the second argument), so also it requires an explanation in terms of final cause or purpose. In this case also, the final cause, the goal at which all purposes aim, is God. (Ibid., 54-56.)

All five arguments depend for their force upon the idea of causality. Mascall recognizes that this idea has been banished from modern physics, although it seems to continue to play a role in such sciences as biology and psychology. Even if it were wholly removed from science, however, this would not affect the force of the arguments. Causality as treated in these arguments is a purely metaphysical idea that is not dependent for its validity upon its relevance in the special sciences. (Ibid., p. 45.)

It will be clear to even the casual reader, however, that the formulations above are vulnerable to many other objections. This is due partly to their very brief and vague formulation here, but even in the more adequate statements of Thomas and in Mascallís account of Thomasí arguments, they remain vulnerable. Mascall, like most contemporary Thomists, fully recognizes that these arguments require extensive elaboration if they are to be rendered defensible in our day. This elaboration consists in the end in presenting the five arguments as five aspects of a single argument that Thomists find implicit but unclearly expressed in all of them. (Ibid., p.40; Existence and Analogy, p. 79.) It is this single fundamental argument rather than the explanations of the five arguments in its terms that is important to us in understanding contemporary Thomist natural theology.

This one argument can be formulated very simply.

Formulations are found in He Who is, pp. 37-39, 65, 95; Existence and Analogy, pp. 68-69,85, 89-90.

Every entity that we encounter in the world is finite. This finitude consists among other things in a lack of the power to cause or sustain its own being. Thus the cause of the being of all things lies outside of them. That which can give being to everything that is cannot be understood as one finite entity among others, or as merely the first in a long series of causal agents. Since Thomas did not believe that the denial of the eternity of the world could be established by reason, his argument to a first cause should not be construed as an argument for a first member of a temporal sequence. (Existence and Analogy, pp. 72-76.) The first cause must belong to an entirely different order of reality. Furthermore, it must differ from all finite entities in having the ground or power of its being in itself, for otherwise we would have to posit an infinite regression of beings deriving their being from other beings.

From this perspective we can see clearly what is valid in Thomasí arguments. Each of them points to some aspect of finitude and insufficiency on the part of the entities in our world, on the basis of which we are driven to recognize a self-sufficient cause of a wholly different order. The first argument points to the lack of self-sufficiency of change; the second, to that of endurance in being. The third shows that the totality of finite beings must still remain contingent and hence dependent for its being on that which possesses being in itself and by necessity. The fourth and fifth show that the perfections and purposes of finite things share in their finitude and lack of self-sufficiency.

They are all so many expressions of the fact that when our eyes are opened to the finitude, insufficiency, or contingency of ourselves and the environing entities, we perceive every aspect of these entities as pointing directly to a supernatural cause. (Ibid., pp. 71, 78.) This does not deny that there is also a natural order of causation, but the fullest explanation in natural terms does not in any way affect the need for understanding the whole network of natural causes as wholly dependent for its being and preservation upon a supernatural cause. The whole network of natural causes, even if it is supposed to have no temporal beginning or ending, remains radically finite, insufficient, and contingent.

Once we see clearly the fundamental conception underlying Thomasí sometimes unclear formulations, we can also see the fundamental requirement for the acceptance of the argument. It is the simple recognition that there are finite entities and subsequent reflection on what this means. (Who He Is, p. 73.) Philosophically this may be stated as the fact that the essence of finite entities does not imply their existence. (Existence and Analogy, pp. 68-69.) But many ordinary people recognize all this immediately, and while knowing nothing of the philosophical concepts in which it is expressed, live by the knowledge of God which they have. (Who He Is, p. 137.) On the other hand, many sophisticated intellectuals are prevented by their theories from recognizing the simple fact that there are finite entities.

Mascall sees that if he is to establish his case for natural theology in the context of modern philosophy, he must refute those epistemological views that lead to the denial of the existence of finite entities.

He does this most systematically in Via Media, Ch. 1.)

In this sense, like all Thomists, he defends existentialism. (E.g., Existence and Analogy, Ch.3) He sees also that in our own day many find that human existence, rather than the existence of things objective to man, is the natural starting point, and he has no serious objection to this. So long as the existence of any finite entity is acknowledged, the basic argument follows from its insufficiency to a self-sufficient existent. (Ibid., pp. 167-169)

Nevertheless, Mascallís own procedure is to argue first for the existence of objective finite entities. Their existence is obscured by essentialism because the radical uniqueness of existence is not recognized. Against essentialists, therefore, the task is simply to call attention to the difference between essence and existence. In our day the more acute threat comes from those persons who deny objectivity to essences as well as to individual existents. (He Who Is, p. 83) Their position must be understood and refuted.

If we take the primitive givens of experience as sense data, we seem to be forced to recognize that from their givenness we cannot infer the existence of any entity whatsoever. The argument that these qualities must inhere in an underlying substance can be disposed of by the simple fact that if all our ideas or concepts arise in sense experience, we can have no idea or concept of substance. Hence, it would be absolutely meaningless to affirm a substance even if evidence could be adduced. All that can be spoken or thought of is an endless flow of qualities. All distinction of subject and object and all discrimination of discrete entities evaporates into the one ongoing process. The organization of sense data into objects is the creative and distorting act of mind. (Ibid., pp. 83-84.)

The Thomistic objection to this philosophic development must not be confused with that of idealism. There is no tendency to assign a prior ontological status to either finite minds or to impersonal reason. The primacy of experience as the normal starting point for all knowledge is fully recognized, but the Thomist insists that along with sense experience man has the equally primary faculty of judgment, whose object is the existence of the entities that are sensuously apprehended. We do not in fact know only patches of brown and green. We know existent entities that are of definite shape and color. This knowledge is a work of the mind that can never occur apart from sense experience but that is not limited to the mere reception of that experience. (Ibid., p. 65; Existence and Analogy, pp. 53-57; Words and Images, pp. 30ff., 63.) The mind may, of course, be in error in its judgments, but this does not mean that it is always or usually in error in attributing existence to things. (He Who Is, pp. 84-85.)

It must be stressed that we do not first recognize finite existents when we have understood the epistemological theory that explains how we recognize them as such. The theory is a description of a fact of common experience. The fact and not the theory is the basis for the natural knowledge of God. The theory is needed only to refute those who suppose that common experience must be illusory because it cannot be explained philosophically.

Thus far we have considered only the basis on which the existence of God is rationally affirmed. It is constituted essentially by the immediate implication of the awareness of the world as it is in its finite existence. We must ask next what it is that is implied in this argument.

First of all, and most essentially, we know that God possesses precisely those characteristics the absence of which in finite things causes us to perceive that God is their cause. That is, God is self-existent, infinite, self-sufficient, and necessary. (Ibid., p. 96.) This is clear to anyone who considers what is involved in finitude, since to attribute finitude to what one called God would simply postpone the real question of God. We can also say that God is the cause of all that is finite as well as the cause of his own being, for it is just as the self-causing cause of all things that we have come to know his existence. Furthermore, God is changeless, for we have seen that whatever changes must be subject to a source of change and that ultimately this must be a source of change that does not itself change.

At this point, however, we confront an acute problem. It seems that if we are to speak of God as cause of the world we must mean something more by the term ďGodĒ than that he is cause. Hume showed that if all we affirm is that an absolutely mysterious X is responsible for all that is, agnostics will have little reason to object. Certainly as Christians we must affirm much more of God than this purely causal relation to the world. But every term or concept that we employ has arisen and received its meaning in our relations with finite things. Since we know that God is not finite, else he would not be God, how can we apply to him ideas that belong properly only to the finite sphere? (Existence and Analogy, pp. 86-87, 92-93,96.)

One answer is that we cannot apply any terms to God except by way of negation. According to this view we cannot know what God is; we can only know what God is not. But this position does not escape the objection of Hume and is entirely inadequate in relation to the Christian revelation of God as living and loving and acting in history.

If we are to speak affirmatively about God, as we must, we seem to have two choices. (Ibid., p.97.) On the one hand, we could assert that the meaning of terms as applied to the finite and to God is univocal. This would mean that Godís life and love are in specifiable respects identical with finite life and love. But to assert this would necessarily imply that in some respect God is finite, contingent, and lacking in self-sufficiency. This, in turn, would run counter to the whole basis of constructing the natural theology.

On the other hand, we could state that terms as applied to God are purely equivocal. This would imply that no aspect of their meaning in one context could be carried over to the other. Since the meaning of life and love as we use these terms is necessarily derived from the finite sphere, we would be forced to acknowledge that our use of these terms with respect to God could only be ejaculatoryóin no way cognitive. We would be left claiming the existence of that about which nothing whatsoever could be said or thought.

Either of these alternatives would leave us in the impossible position of abandoning or contradicting the foundations of the argument to which it is supposed to give expression. The only possibility of maintaining the general Thomist position is to develop a third way between the univocal and the equivocal. This third way is formulated in the doctrine of analogy to which Mascall devotes considerable attention. (Ibid., pp. 98ff.)

Mascallís careful analysis does not persuade him that a clear and convincing doctrine of analogy can be formulated that is free from mystery and logical difficulties. (Ibid., pp. 116, 121.) On the contrary, he appeals to a kind of intuition of general intelligibility rather than claiming a logically unexceptionable statement. This would be a serious weakness in Mascallís total position except for the fact that he does not believe that the reality of intelligible analogical discourse depends upon its adequate explanation.

The case here is parallel to that with respect to our knowledge of finite existents as such. This knowledge occurs first, and our account of how it occurs follows. One need not have an impregnable doctrine of how it occurs to see that it does occur. Similarly, it is clear to Mascall that Christians do talk meaningfully about God without applying terms to him univocally. Hence, analogical discourse about God does occur. The task of the philosopher is not to prove this fact, but only to describe and explain it as far as possible. It is only when we know that infinite being exists and that we can think meaningfully about it that we approach the problem of analogy properly. (Ibid., pp.94, 121; Words and Images, 103.)

Mascall shows, then, that discourse about God employs two kinds of analogies in close interconnection: the analogy of attribution and the analogy of proportionality. (Existence and Analogy p. 101.) The analogy of attribution is that of attributing to God as cause whatever perfection is found in the world as effect. But taken in itself this tells us nothing about God except that he is cause of this effect, that is, in Scholastic terminology it tells us nothing formally about God. (Ibid., p.102.) Hence, we need to supplement this with the analogy of proportionality, which asserts that the relation of such perfections of God as life and love to Godís existence resembles the relation of finite perfections to the finite existents that participate in them. In this way we do speak formally of God, but we must recognize that the resemblance between the two pairs of terms is by no means one of equality. We cannot say that Godís life or goodness is related to his existence just as our life or goodness is related to our existence, for his life and goodness are his existence. (Ibid., pp. 103-112.) This means that by itself the analogy of proportionality provides us with no knowledge about God and is compatible with agnosticism. (Ibid., p. 113.) Mascall believes, however, that when this analogy is held in closest relation to the analogy of attribution, we are enabled to speak of God both meaningfully and formally.

The real conclusion of this crucial discussion of analogy is that at the level of concept we have no real alternative to the univocal and equivocal modes of discourse, but that our thought about God consists in judgments about existence rather than concepts. Since God is He Who Is, that is, pure being, every attribute of God is only a way of speaking of his one act of existing. With respect to God, unlike all other beings, we can have no knowledge of essence apart from existence. (Ibid., pp. 88, 117-120.)

In terms of his natural theology, Mascall does not hesitate to deal with one of the most controversial of traditional doctrines about God, namely the doctrine that God is impassible. Mascall notes that in our century many theologians have surrendered this doctrine, and he recognizes that there is an apparent difficulty in reconciling it with Godís love. (Ibid., pp. 134-135.) Nevertheless, Mascall argues that the doctrine follows from the basic position and that it is also religiously important.

Those who have abandoned the doctrine of the impassibility of God have generally been those who have lost the sense of the divine transcendence. (Ibid., pp. 135-137.) Once we think of God essentially in the immanent order, we cannot think of him as free from the change and suffering of that order. But then we have lost sight of the Biblical God, He Who Is, the author of all being.

This is not to say, however, that a problem does not exist for those who do understand the divine transcendence. (Ibid., p.135.) They, too, are concerned to affirm Godís compassion for his creatures as an essential part of the Christian message. But compassion does seem to imply that the one who feels it is affected by the fortunes of the one for whom it is felt. If so, then Godís impassibility is incompatible with his love.

Mascallís solution is highly interesting. God does know and love the world as well as himself. If we conceived of God and the world as two entities that could be added together to make a whole larger than either one, then it would follow that Godís love for the world implied passibility in God. But this addition is illegitimate. God and the world are not commensurate entities in this sense, since God is infinite and the world finite. Hence Godís real knowledge and love of the world neither add nor subtract from his being in himself. In his own being he enjoys perfect beatitude. His knowledge and love of the world do not affect this beatitude. (Ibid., p.141. Cf. also pp. 132-133.)

Clearly this means that Godís knowledge and love are quite different from that which is operative in the finite sphere. But just this is what we must expect. We have already seen that we do not attribute such qualities to God univocally but analogically. We have seen also that they are thereby understood as ways of talking about the one wholly mysterious act of existing by which God eternally constitutes himself. Hence, the proper analogical predication of love and knowledge to God does not contradict his impassibility as would be the case if predication were univocal.

Mascall is aware that this subtle philosophical argument will leave the plain man unsatisfied. If Godís compassion for him does not affect God, he cannot take much satisfaction from that compassion. But Mascall thinks that what men really need is not sympathy in the sense of feelings but help of a practical kind. Godís compassion expresses itself as the gift of all good things to his creatures. (Ibid., p. 142.)

Furthermore, what is religiously important to us is not that we believe that God is involved in our problems and suffering. It is far better to know that there is one who is altogether free from and victorious over all evil and who offers to us the ultimate privilege of sharing with him in his blessedness. (Ibid., p. 143.) Since it is in this context that we are primarily to understand the work of Christ, this will provide a suitable point for transition from a discussion of God and creation primarily based upon natural theology to a very brief statement about Christ and salvation primarily based upon revelation.

It has already been made clear that this transition is not a sharp one. Mascall, like Thomas, moves back and forth in his discussion between natural and revealed theology. He is much clearer than is Thomas that the actual practice of natural theology depends historically upon revelation. (Via Media, p. 1.) Indeed, only as nature is healed by grace can reason function properly. (Christ, the Christian and the Church, p. 233.) Furthermore, many of the discussions in which philosophy plays the primary role consist in developing distinctions or new concepts that make possible the intelligent affirmation of doctrines that are believed strictly on the grounds of revelation. Hence, natural and revealed theology are quite inseparable. Nevertheless, Mascall insists that a systematic difference between natural theology and revealed theology exists and has great importance. (Ibid., pp. 234 ff.)

Natural theology is that part of our religious thinking which does not appeal for its warrant to revelation, unless we speak of nature itself as general revelation. It consists entirely in the rational reflection upon the universal nature of finite things and the implication of this nature for our thought about God. By contrast, revealed theology takes as its starting point the whole richness of the existing faith of the church. Its task is to make explicit the revelation that is committed to the church. (Ibid., p.241.)

The task of the theologian can be fulfilled only to the degree that he participates actually in the life of the church. (Ibid., p. 239) Theology does not consist of the describing of beliefs held about God by a designated group of persons but of the affirming about God and creatures in their relation to God of that which it has been given to the church to know. (Ibid., pp. 228-229.) For this purpose Scripture and its ecclesiastical interpretation in their indissoluble unity are both necessary. (Ibid., p. 242.)

The revelation consists first and foremost in the person of Jesus Christ himself, but this can become material for theological use only as it is given in human language. This is done in the words of Jesus and in the Bible. But the Bible does not itself provide us with systematic theological formulations. It is rather like a mine from which the greatest variety of materials can be quarried. Therefore, inspiration is needed for its correct interpretation just as for its writing. This inspiration occurs not through individuals but through the whole church, through whose total life and particular decisions dogma are formulated. The theologian works with these dogma that are taken as inspired interpretations of the inspired Scripture. (Ibid., pp. 230-232.)

Clearly, this account of the method by which the theologian works has substantive presuppositions as to the content of theology. For example, if one understood by the church simply the historically given communities with their multiplicity of beliefs and practices, the view of theology as the articulation of the churchís faith would lead to a plurality of theologies that could hardly escape the recognition of their relativity with respect to historical factors. Mascall, on the contrary, assumes that theology is concerned only with the truth itself and that the received dogma embodies that truth. This presupposes an understanding of the church as a supernatural community in which truth is authenticated. In concluding this exposition of Mascallís theological position, therefore, we will survey the history of Godís acts for man as these in turn explain the situation of the theologian.

Mascall believes, first, that although the body of man may have evolved, the immortal soul of man was directly created by God and conjoined to his body at some point in the evolutionary ascent. (E. L. Mascall, The Importance of Being Human: Some Aspects of the Christian Doctrine of Man, p. 14.) The first union of human soul and body was in Adam. (Christ, the Christian and the Church, p. 150.) Adamís sin against God lost for himself and for his descendants the union with God that had been granted to him (Ibid., pp.139-140) and that profoundly affected their human nature as well. (Ibid., p. 233.) The temptation that led to this sin as well as to the other evil in the created order is to be explained by the previous rebellion of angels. (The Importance of Being Human, pp. 77-83.)

Although the very great seriousness of the consequences of the Fall of man is not to be denied, we must not go to the extreme of supposing that all capacities for good were lost. Even fallen man is the suitable object of Godís supernatural grace, a grace that has operated even apart from any knowledge of Godís new act of creation in Christ. (Christ, the Christian and the Church, p. 150.) This act, however, by which God created a new manhood out of the material of fallen humanity, is his supreme work. (Ibid., p. 73.)

In Christ, God himself took the form of flesh. This act is supremely mysterious, but Mascall shows that considerable clarity can be attained in its exposition. He affirms that the personal subject is the second person of the Trinity, who unites to his divine nature an impersonal and unfallen human nature consisting of both body and soul. (Ibid., pp. 2ff.) The union is to be understood as the taking up of human nature into the divine rather than of the lowering of the divine nature to the conditions of the human. (Ibid., p. 48.) Hence, we are not to think of the divine nature as abandoning its divine powers and knowledge in the incarnation. Rather we are to think of Jesusí human nature as informed and transformed by its union with this divine nature without in any way ceasing to be human. (Ibid., pp. 53-56.)

By this act of recreating human nature, God mysteriously created the new possibility of individual manís divinization through incorporation into that glorified nature. (Ibid., p. 78.) This incorporation occurs through baptism and continues through the process of sanctification. (Ibid., pp. 83-84.) The church is the continuing body of which Christ is the head. (Ibid., p. 109ff.) Through participation in Christís body we participate in his union with God. (Ibid., p. 211.) The Eucharist is primarily the cause and secondarily the expression of the unity in the church and with God. (Ibid., p. 193.)

At this juncture we turn from a primarily expository to a primarily critical presentation of Mascallís position. This criticism has considerable importance in view of the fact that, on the one hand, Thomism has had a long and impressive history, maintaining its intellectual authority over a large portion of responsible Christian thought and, on the other hand, it is radically rejected by most Protestant theologians, including all those treated in the following chapters. If we are to understand why Protestant thinkers today accept the peculiar difficulties that confront them when they reject the kind of natural theology that Thomism represents, we must understand the systematic difficulties that Thomism itself encounters.

In the first place, we must return to the peculiar situation in which Mascall finds himself in claiming rational necessity for a position that most rational people reject. He explains this situation by showing that a certain habit of mind is required in order that the data of natural theology be allowed to present themselves to the viewer. Once these data are presented, the argument follows by necessity. (Existence and Analogy, p. xi; He Who Is, p. 75.) Does this account provide the escape from the relativism of philosophic positions that is essential for Thomistic natural theology?

It seems to me that it does not, or rather, that an additional and doubtful assumption is required for it to do so. If we first assume that the perception of things as finite existents is the natural perception for man, then we may assert with Mascall that what inhibits this vision blinds us to what is as it is. Then we may argue with him that the philosophy that follows from this vision is the one true philosophy. But according to Mascallís own account, few if any thinkers had understood their experience in this way prior to the time of the great Scholastics, and they did so under the influence of Hebraic modes of thought. Can we say that what we learned to see only under the influence of revelation is in fact the one natural way of seeing things?

It might be argued that the failure of thinkers to accept the data as they really are has been due to special factors such as their preoccupation with forms or essences and that common people have always viewed things as finite existents. But again, by Mascallís own account, such a vision apart from philosophic sophistication leads to a fundamental understanding of God that was absent apart from the special historical influence of revelation. Hence, the absence of the Christian understanding of God in pre-Christian religion indicates that the vision of things as finite existents was virtually absent for common sense as well as for philosophy until the impact of Biblical thought caused it to prevail.

The point of the foregoing is that the distinction which is made by Mascall between the historic and the systematic dependence of natural theology on revelation has an even smaller relevance than he seems to suppose. The distinction would be important if the vision of things as finite existents were in fact universal but had been brought to clear consciousness only by revelation. But if in fact in the common vision of reality apart from revelation this element has been subordinate to other elements or entirely lacking, then we must acknowledge that revelation creates the data on the basis of which natural theology reasons. These data may be created for some who do not acknowledge the revelation as authoritative, and for this reason natural theology may have a wider basis of acceptance than revealed theology. But we must recognize that natural theology receives a basis on which to operate only as a gift from revelation.

This criticism of Mascall does not have serious consequences for the content of his position. Although he tends at times to obscure the dependence of natural theology upon revelation, he is not unaware of it, and his arguments do not depend on the occasional oversight. However, the relation between theology and philosophy is markedly altered once we fully recognize that the starting point of philosophy, that is, the fundamental vision with which the thinker begins, is historically conditioned and that Christian faith has played a major role in the formation of the Western vision.

Systematically, it seems that a fundamental decision must be made. If the data of philosophical reason are natural, that is, if they are given for human experience independently of historical conditions, then natural theology as commonly understood becomes a major possibility. If, however, the data for human experience are historically conditioned, and if the Christian arguments from philosophy presuppose distinctively Christian data, then it seems less misleading to call the philosophy in question Christian philosophy rather than natural theology. In this case, we seem led to the Augustinian view, in which reason plays its role in interpreting and developing the starting point given in faith.

Mascallís actual position seems to fall between these two alternatives. He sees that the vision of existence from which his natural theology arises depends historically on Christian revelation, but he does not think that it is simply a part of the truth that is given in revelation. It remains a separate starting point for thought from that which God has directly revealed in Jesus Christ. This starting point, although historically formed, has a much wider acceptance than has special revelation, being acceptable to many who consciously reject that revelation. Hence, a clear distinction should be kept between natural theology and revealed theology.

This intermediate position appears eminently sensible. To continue to call the philosophy conditioned by revelation simply natural theology may, however, perpetuate a confusion that is manifest even in Mascallís own thought. I suggest that the term ďChristian natural theologyĒ might be used.

There are no clearly established distinctions between Christian philosophy, Christian natural theology, and natural theology. I am using ďnatural theologyĒ to refer to conclusions of philosophical inquiry supportive of some Christian teaching from data that are understood to be factually and logically independent of Christian revelation. I am suggesting here that when the data are recognized as historically dependent on Christian revelation, we should call the rational conclusions from these data ďChristian philosophyĒ or ďChristian natural theology.Ē By Christian philosophy I mean any attempt to build a comprehensive scheme of ideas on the basis of distinctively Christian data. By Christian natural theology I mean the attempt to justify certain Christian beliefs rationally on the basis of data that, though historically conditioned by Christian revelation, are widely held by persons who are not self-consciously Christian. In these terms Christian philosophy and Christian natural theology, though distinct, are intimately related and fully compatible with each other.)

It should then be recognized that as an apologetic device its sphere of relevance is limited to those whose vision has been consciously or unconsciously already modified by Christian faith. It cannot provide a basis for justifying the Christian doctrine of God to one who stands radically outside the Christian circle.

Emphasizing more consistently than Mascall the historical relativity and conditionedness of the data upon which he builds his thought, let us still acknowledge that for many of us such data are nonetheless very real and important. Let us further acknowledge that, although this vision has dimmed considerably from the Western mentality, much of it remains latent in such a way that a vivid presentation of its importance still has widespread effectiveness. We can then consider whether the implications that a Thomist like Mascall draws from these data actually follow with the necessity that he claims.

The fundamental characteristic of finite entities on the basis of which the whole system of thought is constructed is their contingency, which may otherwise be expressed as the separability of existence from essence. It is because there is nothing in the nature of the finite thing to afford it existence that we must posit a source of being that does contain its own ground of existence. That is, we recognize that there must be some being whose essence does imply or contain its existence. This being is then self-sufficient or necessary. Thus far, given the original vision of finite existents as contingent, reason seems necessarily to carry us. We cannot understand how there can be existent things at all unless there is somewhere a being that is the cause both of their existence and its own.

From this, however, Mascall draws conclusions that seem to be in considerable tension with the Biblical view of God. The Bible seems to present God as one who is in loving interaction with his creatures in such a way that he is affected by what happens to them. Mascall, loyal to the Thomist natural theology, argues that God is strictly changeless and, therefore, unmoved by our suffering. His love is pure act without shadow of passivity. Thus he sets himself sharply against all those who have stated that Jesus reveals God as suffering for and with man.

We must ask here whether the conclusion that God cannot be affected by events within his creation in fact follows from the fundamental argument from contingent to necessary being. Mascall thinks that it does, and indeed he seems to regard this as so evident as to require little explanation. However, recent philosophers, especially Charles Hartshorne, have proposed other interpretations of God that combine the doctrine of his necessity with the view that he is capable of being affected by the course of events.

See especially Hartshorneís Manís Vision of God and Philosophers Speak of God, pp. 499-514.

The central issue is whether the necessity of God implies absolute immutability. The argument for this implication seems to be that if God is necessary being there can be nothing contingent about him. A being that is partly necessary and partly contingent would seem to be in its totality and wholeness not necessary, and hence, according to the argument, not God. But if everything about God is necessary, then nothing could ever have come to be in or for him; that is, he is strictly immutable. Phrased in this way the argument seems quite convincing.

However, the proper starting point as established by the original argument from the contingent to the necessary is not ďnecessary beingĒ as such, but a being whose existence is necessary. This is all that the argument warrants. There is then no contradiction in supposing that a being whose existence is necessary may nevertheless alter in some respects in the mode of that existence. That God is must be necessary, hence altogether free from contingency or change; but what God is, beyond the basic fact that he is the ground of his own existence and of all other existents, may without any contradiction contain contingent elements and, therefore, change.

The Thomist objection to this suggestion is that it neglects the crucial categories of essence and existence in terms of which the argument is most rigorously formulated. The lack of self-sufficiency in finite things consists in the separability of essence and existence. That is, it is not of the essence of finite things to exist. In a necessary being, in contrast, it must be of its essence to exist. Hence, in God essence and existence are identical. If so, what God is can only be his is-ness, and all contingency or change is strictly excluded.

I do not believe, however, that this form of the argument affects the possibility of drawing different conclusions. In these terms it must indeed be of the essence of God to exist, but this need not imply the strict identity of essence and existence in God. The assertion that it is of Godís essence to exist does not imply that nothing other than existing can be of Godís essence. It does not exclude the possibility that it is also of the essence of God to be affected by what occurs in the experience of his creatures. This would imply again that it is of Godís essence to include contingent elements.

The upholders of the view that there are contingent elements in God are not arguing that his behavior or character is vacillating and unpredictable. Their major religious concern is to show that we may take seriously the Biblical doctrine of Godís love for his creation without contradicting the necessity of Godís being. If we mean anything at all by asserting that God loves his creatures, we must surely mean that God is not indifferent to the events in their lives. But if God cares, then to some degree the total experience that is God is affected by contingent events and is itself contingent.

A second line of argument against the presence of any contingent element in God stems from the doctrine that God is Being. This doctrine has two foundations: the first, Biblical; the second, philosophical. The first can be summarized as follows. At the one point in the Bible where God reveals his name he affirms himself as He Who Is, thus as pure being or existence. Therefore, the philosophical doctrine of God as Being is demanded by revelation. However, Mascall himself recognizes that the interpretation of the passage in question in these terms is highly doubtful. He wishes to base the doctrine of God as pure Being upon the teaching of the Bible as a whole. (Existence and Analogy, pp. 11-14.) But it is difficult to see that such implications of this doctrine as that God is strictly impassible are admitted in the Bible. If the doctrine itself is not explicit in the Bible, and if its implications are not admitted in the Bible, it is hard to see how the doctrine can be defended on the basis of Biblical revelation.

Mascallís view is that philosophy demands that we maintain the traditional view of the immutability and impassibility of God and that this view is in full harmony with the basic witness of the Bible. I am assuming that this view is in serious tension with the Bible and am arguing that it is not logically required by the philosophical argument. I would go further and say that there are positive philosophic reasons for the alternative suggested, namely, that there are both necessary and contingent elements in God. However, this would exceed the proper scope of the present critique. All that is needed here is to show that Mascallís typical Thomist conclusions do not necessarily follow from his starting point. It is my belief that a still wider hearing could be secured for the starting point if it were clearly seen that it did not entail these traditional consequences.

We are now prepared to discuss Mascallís doctrine of analogy. The discussion will be somewhat more extensive than otherwise appropriate to this context because this doctrine is crucial to other theological positions as well as to that of Thomism. Among those treated in this volume we find Bultmann explicitly appealing to it. Since he provides virtually no explanation or justification of the doctrine, the present critique will have to be regarded as applicable also to him. Tillichís symbolic use of terms also seems vulnerable to much the same criticism.

Mascall acknowledges the limitations of his account of analogy, but the problem seems to be even more acute than he recognizes in his defense. In his presentation, the argument that God exists as self-existent cause of all finite being is established first, and the problem of analogical predication follows. In this situation, since Godís existence as cause of things is known, the objection that nothing further can be said or thought about God univocally might appear as a quibble. It does seem that God must be known somehow from his effects. In this connection Mascall appeals to the analogy of attribution as an essential part of the explanation of how we can speak meaningfully about God.

But all this seems to assume that it is already clear that the terms ďcauseĒ and ďexistenceĒ can be applied to God univocally, whereas I take it that Mascall holds that they are themselves applicable only analogically. If there is no univocal element in the assertion that God is cause of the world, on what basis can one say that the perfection of the world is even virtually (that is, as cause) present in God? This would seem possible only if we understood what was meant by attributing cause to God univocally, at least in so far as our idea of cause tells us that the power of producing the effect must be in the cause. But this would imply some element of univocal meaning in the application of the term ďcauseĒ to Godís relation to the world. Apart from this, the whole basis of the analogy of attribution would seem to be pure equivocation.

Similarly, the analogy of proportionality is formulated in terms of the relation of Godís attributes to his existence. But if we cannot first affirm his existence univocally, it is hard to see that there is any escape here too from pure equivocation. In this situation the combining of the two analogies cannot improve matters. Christian natural theology as Mascall understands it would seem to be impossible.

The fact is that although Mascall quite explicitly affirms the purely analogical character of even causality and existence as applied to God, (Existence and Analogy, p. 87.) he elsewhere seems to assume that these terms are quite clear and definite in their application to God. (Ibid p. 96.) Hence, we should consider the possibility that causality and existence are affirmed univocally of God. This would at least introduce the possibility of approaching the doctrine of analogy without sheer bewilderment, but before reconsidering the argument in these terms, we must first note that the acknowledgment that some terms can be applied to God univocally has very significant consequences.

In the first place, if we may speak univocally of God as cause and existing, there seems no reason to doubt that other metaphysical terms have equally univocal application. The whole language of self-sufficiency, necessity, simplicity, immutability, and infinity turns out to be quite univocal.

If Thomists acknowledge these terms to be literal, they must also understand them as negations, since only negative statements about God are literal. This does not affect the fact that whereas metaphysical terms can be literal, Biblical terms are typically analogical.

It appears in the end to be that the doctrine of analogy is required only for the preservation of the Biblical language about God. One need not be surprised if in the conflict between the apparent implications of Biblical concepts, understood to be analogical, with metaphysical concepts, understood to be univocal, it is the implications of the Biblical concepts that give way.

In the second place, this throws quite a different light upon the situation to which Mascall appeals as the real warrant for a doctrine of analogy. This situation, it will be recalled, is that there is in fact meaningful discourse about God. This fact means that the task of the doctrine of analogy is not to justify such discourse but simply to describe and explain it. On this basis, Mascall can recognize the logical inadequacy of his account and still insist that it is sufficient for its purposes.

But if Mascallís own assumptions explain that the meaningfulness of a good deal of discourse about God can be understood in terms of the univocal use of metaphysical concepts, then it is only the use of the apparently incongruent religious language that requires special explanation. On the two hypotheses that this language is meaningful and that his philosophy is correct, the fact of analogical discourse, defined as meaningful, nonunivocal discourse, follows. But this argument is unusually weak in view of the fact that both hypotheses are doubtful, and the conclusion may not be meaningful at all.

The first hypothesis will be denied not only by positivists but also by philosophers who take seriously the religious implications of a doctrine of God as infinite, immutable, simple, and necessary. They will hold that popular religion attempts to think about this God in terms that actually do not apply at all.

Others, such as Brunner, will agree that the tension between the two sets of categories implies their strict incompatibility but will understand that this means that the Biblical categories, based on revelation, must altogether supersede the philosophic categories, based on corrupted reason. Although this position does not deny Mascallís first hypothesis and does not philosophically dispute the second, it places them on such different levels as to destroy their force.

The second hypothesis can also be directly attacked philosophically. This can be done from many points of view, but I have suggested above that the crucial attack is that which accepts the same data and then shows that the argument does not exclude the presence of contingent elements in Godís total nature. Like all the other criticisms, this makes it possible to avoid the doctrine of analogy. Hence, it is clear that the meaningfulness of religious language can be accepted without entailing any doctrine of analogy. Religious language, however much it may be poetically elaborated, can be seen to have, at its base, affirmations that, whether they are true or false, have univocal meaning.

This may be illustrated briefly. Mascall affirms that the assertion that God is living is neither univocal nor equivocal, but analogical. If Mascallís philosophic doctrine that God is absolutely immutable is accepted, we must agree that we cannot assert life of God univocally. As an alternative approach, we may take certain possible definitions of life and ask whether or not they might apply univocally to God. If we define life in terms of generation and decay, it is quite clear that we must deny that God is characterized by life, since these characteristics are incompatible with the necessity of his being. If, however, we define life in terms of the capacity to respond selectively to events, a conception of God that allows some contingent elements in his experience will permit us to apply the term ďlifeĒ to God univocally. It may, of course, not be factually the case that God responds selectively to events, but that he might do so quite literally is not ruled out by our knowledge that Godís being is necessary. Furthermore, if we quite univocally call God living in this way, this does not imply that Godís life is in other respects like ours. Indeed, we may be able quite univocally to show ways in which his life necessarily differs from ours. Finally, a great deal about God must surely remain wholly unknown to us. But nowhere are we forced to introduce a kind of meaning that is neither univocal nor equivocal.

I have not tried in these comments to prove in detail the ambiguity and inadequacy of Mascallís account of analogy. His own commendable clarity and frankness cause him to display and acknowledge these limitations himself. He poses the issue as that of explaining what he supposes manifestly occurs, that is, meaningful but nonunivocal discourse about God. He knows that he has not fully succeeded in explaining this possibility. Hence, to say that he has not done so is not an argument against him. Therefore, I have confined myself to showing that the existence of meaningful discourse about God as a necessary being does not imply that there is meaningful nonunivocal discourse. From this it follows that there may well be no such thing as analogical discourse.

Thus far the criticism of Mascall has been that his data are even more radically conditioned than he has recognized and that they do not necessarily lead to all the conclusions that he draws from them. The alternative set of conclusions has the advantage of being in less tension with the Bible and also of not requiring the confusing doctrine of analogical discourse as a third way between the univocal and the equivocal. We must now ask, granted that Mascallís Thomist conclusions do not follow necessarily from these data in all respects, whether they constitute an intelligible and self-consistent position that does account for the data.

In this volume, I am not undertaking to criticize philosophical ideas philosophically. I am not asking here whether Thomism as a philosophy can survive systematic analysis and criticism. Indeed, I am assuming that in general it can do so. Our question is, instead, whether the theological affirmations made by the Thomist are intelligible within the context of his philosophical doctrines.

I have already indicated that I perceive a tension between the Thomist doctrines and the thought patterns of the Bible. The point was made in terms of the tension between Godís compassionate love and his impassibility. However, there can be no question that the theological doctrine of Godís impassibility is compatible with, and indeed demanded by, the philosophical doctrine. We must now ask whether the Thomist is willing to tailor all of his theological doctrines to fit the demands of his philosophy. If so, we might deny that the total position is Biblical, but we would also recognize its internal consistency.

A crucial question concerns the understanding of God as personal. Thomism certainly intends to make this affirmation. It speaks of God in terms of intellect, will, and memory, and it attributes acts and purposes to him. Does this make sense in the light of the doctrine that in God there is no element of contingency or change?

Clearly, all of this language about God must be understood as analogical discourse. What we humans know as intellect, will, memory, activity, and purpose involves contingency and change. But even if we allowed the possibility of analogical discourse, could we attribute even the vaguest meaning to these terms when they are applied to infinite, necessary, simple Being? Or, if the demand for intelligibility is illegitimate, can we see any reason whatever for attributing the terms to God? According to Mascallís own account of the ďlifeĒ of God it seems clear that all these terms can be only so many ways of referring to the pure act of existing that is God. In Godís own being, presumably, the distinctions suggested by these terms have no place. But if all these terms when applied to God refer ultimately to the one act that we can more accurately call existing, I am unable to see how we can regard the use of terms like these as analogical rather than simply equivocal.

Mascallís argument, we have seen, is that in fact we do discuss meaningfully about God in these terms without claiming that our use is univocal. I argued above that it is quite possible that the meaningful portion of our discussion about God does use terms univocally. I wish to argue now that it seems likely that the appearance of meaningful nonunivocal discourse about God is due to historical factors, and that when these are understood, the appearance is destroyed.

I have already indicated that I believe the data on which Thomist theology bases its affirmation of God are derived historically from Christian revelation. Hence, in an important sense the Thomist philosophical doctrine of God is Christian. Nevertheless, its original formulation was profoundly influenced also by Aristotelian philosophy and took over much of what Aristotle had said about a self-sufficient prime mover. (Pre-Thomist thought about God also involved a synthesis of Biblical and Greek categories and, therefore, posed much the same problems.)

The doctrines of God derived from this influence have stood through the centuries in marked tension with Biblical personalism. Theological discourse has been caught in this tension and has included assertions that, when taken univocally, must be regarded as mutually contradictory.

The ecclesiastical sanctioning of this way of thought has forced generations of thinkers to expend great ingenuity on the acute rational problems that are involved. They have certainly carried on meaningful discourse with one another about the problems. Furthermore, the ordinary Christians who acknowledge the situation as defined by the approved theologians have found meaning within this context. In this situation the doctrine of analogy, namely that meaningful language need not be univocal, necessarily played a large role.

However, none of this proves that, in fact, meaningful discourse about God takes place that does not use terms univocally. It would seem, therefore, that we can understand historically why persons find themselves talking in this context without supposing that they are forced to do so by the nature of things or by their apprehension of God as the cause of finite beings. Since this is so, and since no satisfactory doctrine of analogy exists,

Perhaps the most promising discussion is that of Austin Farrer, much of which is summarized appreciatively by Mascall in Existence and Analogy, pp. 158-175; and Words and images, pp. 109-120.

we must declare that the attribution to God by Thomists both of immutability and of personal characteristics is an inconsistency. More specifically, since it is the personal characteristics rather than the immutability that are held to be analogical, we must declare that Thomists have not yet shown us that, given their philosophical doctrine of God, the attribution of personal characteristics to him is not pure equivocation.

This point has been pressed not only for the systematic reason that it appears to be a real weakness in the Thomist position but also because much of modern Protestant thought can be understood only against the background assumption that philosophical theology of the Thomist type must necessarily lead to conclusions that diverge from the Biblical understanding of God. Some have held that this must follow from the use of any philosophy whatsoever. Others have identified this consequence with the use of metaphysical, in contradistinction to cosmological, philosophy. Still others accept the implication that God is not properly understood as personal.

This rather lengthy criticism of Mascallís Christian natural theology, however, is not intended to show the necessity of its radical rejection. Quite the contrary, its purpose is to argue that the fundamental Thomist vision of finite existence as pointing to its self-sufficient cause is fully compatible with a doctrine of God that can embody the real strengths of the Thomist position without entailing its religiously and logically unsatisfactory conclusions. This has been shown in the philosophical work of Charles Hartshorne.

In conclusion, the same problem of the relation of Mascallís philosophy and Biblical thought should be stated in a distinctively Protestant way. I have repeatedly affirmed that there appeared to be serious tensions between the Biblical understanding of God and that which emerges in Thomist natural theology. The Catholic basis for denying this tension lies in the argument that Scripture must be read as interpreted in the ecclesiastical tradition. If this principle is followed, it must be granted that one will not find in the Bible the univocally personalistic thinking about God that many Protestants suppose they see. That is to say, the church has in fact interpreted the Bible since early times in terms of some of those ideas about God which Thomism embodies in its natural theology.

The Protestant objection is that we can in fact gain a more objective view of the Bible by direct study and can criticize the traditional interpretation from this point of view. To this Mascall has replied that the Bible can be used in favor of an indefinite number of systematic positions and that it cannot be used fairly to support one such position against others. Systematic theology must depend upon the inspired interpretation of the Scripture. If it is to do more than organize the private interpretation of one person, it must assume that Godís Spirit has been at work in the whole church. The theologian must take the Catholic tradition that has resulted from the guidance of the Spirit as his authoritative guide.

We must ask two questions of decisive importance. First, is it true that the Bible is open to a virtually unlimited number of systematic interpretations? The Reformers thought that its message was quite clear and needed little or no interpretation, but the history of Protestantism seems to support the Catholic claim. Nevertheless, the Protestant cannot admit total relativity of interpretation. If one cannot say definitively what the Biblical teaching is, one can at least specify some things that it is not.

This much a Catholic may also acknowledge. Hence, the real issue is the second. Is the Catholic traditional interpretation of the Bible one of those which can be known on the basis of our present study of the Bible to be in serious error? If not, then the assertion that there are important tensions between some of the approved philosophical doctrines of Thomism and the Bible is unsubstantiated. If it is, then the Reformers were right in demanding a choice between the Bible and Catholic tradition, and we will be right today in reaffirming that demand. An answer to this question can be approximated only by open and scholarly investigation.