AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

Ernst Cassirer

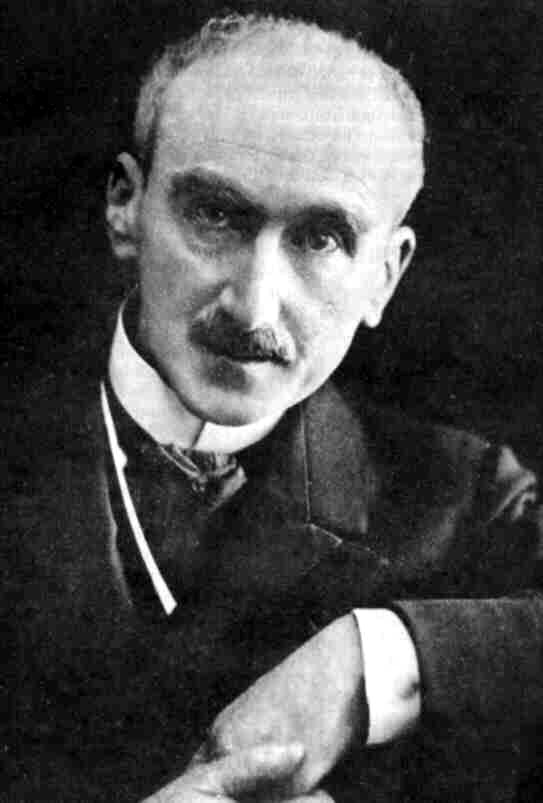

Henri Bergson

From Process Studies, Vol. 32, Number 1, Spring-Summer 2003, 79-93.

Posted July 30, 2008

“. . . Cassirer’s epistemological standpoint on symbols can be enhanced with the metaphysical standpoint of Alfred North Whitehead and Henri Bergson. . . . [and] may be used to enhance Whitehead’s metaphysics. In particular, Whitehead is concerned that metaphysics be appli-cable, and the framework that Cassirer sets forth . . . creates a solution to the problem of symbolic representation. . . . [T]hese two thinkers complement one another to a great degree.”

Cassirer, Whitehead, and Bergson: Explaining the Development of the Symbol

Eric Dickson

Introduction

It is not easy to understand how a sensible object can convey a meaning. Is there something in the sensuous medium that is peculiarly capable of standing for another thing? Is the meaning conveyed in some ways independent or dependent upon the characteristics of a sensuous medium? Obviously, these questions are complex and can be approached from any number of standpoints. A promising venue of interpretation regarding the issue of how symbols symbolize and signs signify is offered by the philosophical anthropology of Ernst Cassirer. However, as excellent as this account is I believe it can be improved through a supplementation. In particular, I would suggest that Cassirer’s epistemological standpoint on symbols can be enhanced with the metaphysical standpoint of Alfred North Whitehead and Henri Bergson. The blending of these perspectives, while a difficult undertaking, provides in my view an essentially complete interpretation of the relationship between expression and representation in the process of concept formation.

In addition, Cassirer’s epistemological standpoint may be used to enhance Whitehead’s metaphysics. In particular, Whitehead is concerned that metaphysics be applicable, and the framework that Cassirer sets forth—and which I fill in using Whitehead—creates a solution to the problem of symbolic representation. While Whitehead is good at creating metaphysical systems to explain phenomena at a general level, he gave little attention to detailed historical analysis. This is the reverse of Cassirer, who wrote many detailed analyses regarding the development of conscious-ness but avoided making metaphysical claims. The point is that these two thinkers complement one another to a great degree. However, rather than show this full complementation, I will focus on enhancing the thought of Cassirer, by using Whitehead and leave the other half of this project for another time.

Since general familiarity with Cassirer’s theory of symbols cannot be assumed, I will begin with a summary of his account. However, this summary is not intended to offer a complete survey of Cassirer’s symbol theory but, rather, concentrates upon the relationship between the expressive function of symbolic consciousness and the representational function. I focus especially upon the transition from expression to representation because it is here that the crucial moves occur in explaining how a sensuous medium can bear a meaning. We share expression with the animal world; representation, so far as we know, is apparently either peculiar to human beings or, at the very least, human beings emphasize representation in their conscious functioning to such a high degree that many believe this emphasis justifies making a distinction in kind between the form of human consciousness and the form of consciousness in other animals.

Following my exegesis of Cassirer, I will call attention to certain shortcomings in his view, which I will suggest, may be overcome with an adequate metaphysics of the symbol. I find Whitehead’s philosophy of the symbol useful for this purpose. The effected synthesis of the symbol theories of Whitehead and Cassirer still leaves unanswered questions. I think those further questions may be addressed by appealing to some of Bergson’s key ideas. In the end I hope that the resulting theory of the manner in which sensible things convey meanings will constitute an interesting place to begin a still more comprehensive account of the relations among language, consciousness, and the physical world.

Cassirer: The Sensuous Medium and the Symbol from an Epistemological Standpoint

Cassirer argues for the existence of symbolic consciousness; i.e., consciousness is understood to be in a symbolic relation with the world. When something in the sensuous medium has meaning, it has this meaning through the functioning of consciousness; consciousness gives phenomena meaning. Cassirer begins his account in a Kantian manner by asking what the conditions must be in order for symbolism to occur, but he develops his account in a Hegelian manner, using a phenomeno-logical analysis in the Hegelian sense, i.e., by tracing the development of consciousness.1

Should the reader wonder why Cassirer’s standpoint is characterized as epistemological rather than metaphysical, it is because Cassirer does not provide the genetic causes of the development of conscious functioning and concept formation; he attempts only to provide the structure of consciousness.2

His failure to give a genetic account of each element in consciousness leads eventually to the gaps in his account, about which more will be said later.

The three structural levels of human conscious functioning that he identifies are expression (Ausdrucksfunktion), representation (Darstellungs-funktion), and pure significance (reine Bedeutungs-funktion)3

The expressive function is the most basic. Expression is tied to its present existential context and cannot be detached therefrom. For example, a squirrel chattering a warning to other squirrels that a cat is in the yard is a symbolic expression. Human beings also symbolize their immediate surroundings by expressively calling attention to particular features of the situation.4

In the expressive function, meaning is unified with the sensuous medium of the present existential situation. When the situation changes, the meaning disappears along with the sensuous medium through which it was conveyed. Hence, expressive meaning is completely dependent upon sensuous existential conditions. The experiencing subject(s) is part and parcel of the same situation and has no enduring self-identity at this level. Whatever durable identity an experiencing subject may have requires more sophisticated symbolic functioning than pure expression can provide.

In contrast to the contextual dependency of the expressive function of consciousness, the representational function allows the experienced meaning to be detached from its existential situation and carried—by no particular sensuous medium—from one situation to another. Hence, representational meaning at this level of consciousness is independent of the sensuous medium. Clearly, some important transition occurs when experiencing beings move from expressive forms of consciousness into representational forms. How does this transition occur? I will explain both the expressive and the representational functions in more detail below, and then attempt to explain the transition.

(a) The Expressive Function

Cassirer holds that the expressive function is the most basic symbolic function of consciousness. It is of an original character. He argues that it is impossible to derive expression from a bare sensation unless it is original to that sensation not as an appurtenance, but as the total; therefore, expression is immediate and comes wholly formed in a perception.5

In human experience the expressive function and its kind of meaning is preserved in mythical consciousness. For mythical consciousness the symbol, the meaning symbolized, and the existential situation all come together. To think any one of these elements is to think the whole existential situation. Myth does not contain the thing-attribute category, the view of both whole and parts. It sees only the whole. By investigating myth, we can avoid the problem of inserting a theoretical distinction into a description of nature, which is to describe nature not as it is but as it is after a theoretical analysis.

Myth is an expressive world, most evident to us in the present whenever we come into contact with living things. In mythic consciousness, the world is alive. There are no things, only subjects; i.e., “I” and “thou.” The world is animated. “The understanding of expression is essentially earlier than the knowledge of things” (Symbolic Forms III 63).

The “thou” is given; thus other subjects are basic knowledge, not derived. The “I” is the dependent knowledge. Consciousness can only know itself by differentiating itself from its counterpart, the “thou” or the outer world (Symbolic Forms III 89). As this differentiating process moves along, the “thou” of the outer world is gradually replaced by “thous,” and these are then replaced by “its,” i.e., subjects become objects. So, the expressive function gives the experiencing consciousness a world of subjects, alive with activity in a present existential context.

(b) The Representational Function

In the prior section we summarized how, for Cassirer, the mythical world helps us to understand the expressive function. The mythical world is a world of flux, where forms slip into one another. There is little linguistic stability. For example, any god is only a god of the moment, of the event or object or form that is present, and hence there does not exist enough structural stability in consciousness to allow for full-fledged conceptual thought.

Representation is an entirely new level of consciousness, a difference of kind in conscious functioning, not of degree alone. The representa-tional symbol carries meaning across existential contexts. Cassirer focuses on language’s ability to do just this. Somehow language endows the symbol with a power of detachment from, or transcendence of, the material/sensuous mode of conveyance through which it is presented to consciousness.

How does language accomplish this? In representation, a single factor is detached from a total existential milieu; then, through representation, it functions to reconstitute that situation when the situation no longer exists. The whole situation is condensed into this single factor, and it is this movement that allows us to remove the “phenomenon” from the spatial and temporal flux. Also, the condensation of meaning renders the symbol “pregnant.” (I shall discuss this below.) When we recognize similar things, we posit a lingual concept, but positing does not stop here: “It [concept formation in language] does not content itself with positing different things as identical . . . it also composes the individual positings thus gained into comprehensive totalities, into distinct groups and series” (Symbolic Forms III 115). This is how the positings of blue, red, green, and so forth become the totality of color.6

Cassirer points out that, “The decisive act is . . . that within the sequence of these particulars we create definite intervals which provide a characteristic division and articulation . . . certain favored points are gradually singled out, and around them the other members group themselves” (Symbolic Forms III 116). This singling out and subsequent grouping is what forms the structure of the representational function of consciousness.7

The singling out of points and subsequent grouping is the major function of the representational consciousness, and it is this function that allows meaning to become independent of the present existential situation. Grouping is done in abstraction from experience; in fact, it almost always involves the coordination of multiple experiences. This ability to group separate phenomena depends initially on the ability to distinguish pieces of one’s experience from the experience as a whole. An example of this ability is the way representational consciousness distinguishes between a thing and an attribute (Symbolic Forms III 118ff.). That is, we move from the “thou” orientation of the mythic, expressive function to the “it” orientation of the representational function. Only a “thing” can have “attributes.” A “thou” has personal traits, not attributes. For example, the storm god is angry (a personality trait); the storm is violent (attribute). The representational function allows consciousness to hold a phenomenon and consider it as an object or thing. It can then take one of the attributes of these things as yet another thing. The attribute can then function as a symbol, or representation of the whole.

In the representational function of consciousness, consciousness makes itself and its objects of contemplation independent of present existential situations. The experiencing subject is able to build up a complete temporally independent world of symbols. The symbol is born of, or from, a particular existential situation, but it then, somehow, gains the ability to transcend all particular situations. The symbol, once freed from the present situation, then seemingly floats among infinitely many situations, with a power to represent different situations in one condensed symbol. The representational world grows as each object of perception takes on the ability to represent more and more diverse things and more and more diverse functions. The phenomena speak to the consciousness as symbolic elements in a symbolic structure. This symbolic structure is made possible by what Cassirer terms symbolic pregnance. The term pregnance is meant to convey the symbol’s ability to move from one situation to the next and still provide meaning to vastly different situations. A symbol is pregnant with possible meaning.

Cassirer discusses this strange ability in the context of the distinction between matter and form. Matter is the concrete being, or sensuous medium, of the symbol, while form is the varying meaning that is carried along with the symbol. According to Cassirer, the split between the physical and mental world, or the stratum of matter and that of form, rests in the relative independence of the two realms. Although they are never absolutely separable, each seems able to operate without the other. Matter must always be in some form, but it can shift from one mode of signification to another, either through a shift in the modality of meaning or within the restricted sphere of one of the forms (expressing or representing):8

It is with a view to expressing this mutual determination that we introduce the concept and the term “symbolic pregnance.” By symbolic pregnance we mean the way in which a perception as a sensory experience contains at the same time a nonintuitive meaning which it immediately and concretely represents. Here we are not dealing with bare perceptive data, on which some sort of apperceptive acts are later grafted, through which they are interpreted, judged, transformed. Rather, it is the perception itself which by virtue of its own immanent organization, takes on a kind of spiritual articulation—which, being ordered in itself, also belongs to a determinate order of meaning . . . . It is this ideal interwovenness, this relatedness of the single perceptive phenomenon, given here and now, to a characteristic total meaning that the term “pregnance” is meant to designate. (Symbolic Forms III 202)

It is the mutual determination of meaning between structure and material that results in the building of consciousness. The symbolic function is not reducible to any other elements of consciousness because it is the foundation of consciousness. The phenomenon gains objectivity, or symbolic pregnance, by participation in the structure: “The symbolic pregnance that it gains detracts in no way from its concrete abundance; but it does provide a guarantee that this abundance will not simply dissipate itself, but will round itself into a stable, self-contained form” (Symbolic Forms III 203). The object as the perception of a sensory experience has within it the ability to symbolize a multiplicity of unrelated objects. Perception and sensation are still separate but not absolutely. They find their connection in the object, more specifically in the object’s symbolic pregnance.

Cassirer’s account, though promising, leaves us with some questions. While we see that language is the vehicle through which consciousness makes the leap from expression to representation (from dependence on the sensuous existential situation to independence therefrom), we do not see why or how. The closest that we get to how is the discussion of symbolic pregnance. If symbols can move from situation to situation providing meaning in each, and we call this ability symbolic pregnance, then we have not really answered the question of how. We just know that it occurs and have given a name to it. What is needed is some kind of a metaphysics; i.e., we need the being of the symbol, the being of symbolic pregnance. What are these things, really?

Whitehead: The Sensuous Medium and the Symbol from a Metaphysical Standpoint

Now we can begin to approach the genesis of symbolism from a different viewpoint. Whereas Cassirer works outward from consciousness, Whitehead starts with metaphysical categories and works his way toward conscious functioning. For Whitehead, symbolism originates in perception and, therefore, an analysis of his theory concerning perception is in order. He distinguishes among three modes of perception: presentational immediacy, causal efficacy, and conceptual analysis. Presentational immediacy and causal efficacy are joined together through symbolic reference, so that conceptual analysis can then take place. This process, familiar to most readers of Process Studies, will be explained in the following pages, and will assist us in filling out the relationship between expression and representation in conscious experience.

(a) Direct Recognition

Both presentational immediacy and causal efficacy are subsumed under the heading of “direct recognition.” Whitehead defines direct recognition as “that type of mental functioning which by its nature yields immediate acquaintance with fact” (7-8). Direct recognition does not include symbolism. It is bare fact.

(i) Presentational Immediacy

Whitehead defines presentational immediacy throughout Symbolism in an attempt to continue refining the concept for our understanding. I am forced to mimic this approach in an attempt to find my way through the labyrinth of his thought, for if I put the torch aside I fear I would find neither the exit nor the entry nor the bathroom. He first defines presentational immediacy as “the familiar immediate presentation of the contemporary world, by means of our projection of our immediate sensations, determining for us characteristics of contemporary physical entities” (13). Whitehead’s use of the word “projection” is meant to convey the role that our sensory organs play in perception. Our eyes “project” images into space.

Using the example of a wall and a percipient, Whitehead writes that the wall and the percipient share a relation, but each is also independent of the other. Whitehead then refines presentational immediacy by defining it as follows: “It [presentational immediacy] expresses how contemporary events are relevant to each other, and yet preserve a mutual independence” (16). Contemporary events are to be understood as the percipient and the perceived object. Both are processes and, at any point in time, each is an event in time.

Whitehead states that presentational immediacy is what is usually called sense perception, but he makes certain modifications: “Presentational immediacy is our immediate perception of the contemporary external world, appearing as an element constitutive of our own experience. In this appearance the world discloses itself to be a community of actual things, which are actual in the same sense that we are” (21). Here, Whitehead is attempting to separate himself from the sensationalist schools. Not only is he refining their view, but he is also laying the foundation for a new beginning, causal efficacy. The final aspect of presentational immediacy is objectification. Whitehead writes:

presentational immediacy . . . introduce[s] into human experience components which are again analysable into actual things of the actual world and into abstract attributes, qualities, and relations, which express how those other actual things contribute themselves as components to our individual experience . . . . I will therefore say that they [the abstractions] “objectify” for us the actual things in our “environment.” (17)

So, for Whitehead, when we abstract we objectify, and we can only abstract when we have the power of perceiving in the mode of presentational immediacy. He sums up his views on presentational immediacy clearly as follows:

The main facts about presentational immediacy are: (i) that the sense-data involved depend on the percipient organism and its spatial relations to the perceived organisms; (ii) that the contemporary world is exhibited as extended and as a plenum of organisms; (iii) that presentational immediacy is an important factor in the experience of only a few high-grade organisms, and that for the others it is embryonic or entirely negligible. (23)

Presentational immediacy gives us the ability to abstract and objectify. However, unlike the traditional schools of thought, Whitehead does not see this mode of perception as the original mode. That is, abstraction is not a fundamental function. To begin a philosophy with presentational immediacy would be a mistake. The fundamental function, for Whitehead, is causal efficacy.

(ii) Causal Efficacy

Causal Efficacy is the second type of direct recognition. Whitehead states that this mode is one that is common to all organisms, both higher and lower. Causal efficacy is quite simply conformity; conformity in space and conformity in time. To use Whitehead’s language, it is the way in which one event conforms to the conditions of a past event. Whitehead’s explanation of causal efficacy is in almost constant dialogue with the schools of Hume and Kant.

According to Whitehead, both schools make the basic mistake of viewing time as pure succession. This, however, is an abstraction from the actual nature of time. Time conforms. The present conforms to the past. Each epochal occasion includes all that happened before (cf. Cooper for an explanation of how causal efficacy grounds experienced time). By transforming time into pure succession, Hume and Kant cut off the knowledge of cause. “It is not just that, against Hume, we have an experience of causal connection: we have a form of experience which is causal connection” (Machlachlan 229).

As noted above, Whitehead held that presentational immediacy gave the wall and the percipient as independent. But in causal efficacy, independence does not exist. Everything is conformity. The wall and the percipient conform to each other. There is no independent, stationary abstraction.9

(b) Symbolic Reference

Symbolic reference is the joining of the two modes of direct recognition, or pure perception. Symbolic reference results in the world that we know as human beings and, as such, we play a role in this function. It is not a product of conceptual analysis, bur rather the condition for conceptual analysis, because the world does not actually contain any concepts. Concepts are created through abstraction and symbolism.

Whitehead defines symbolism as occurring when an object in experience eliciting the consciousness of another object. Thus we have a symbol, the thing directly perceived, and a meaning, the consciousness of which is elicited by the symbol: “The organic functioning whereby there is transition from the symbol to the meaning will be called ‘symbolic reference.’ This symbolic reference is the active synthetic element contributed by the nature of the percipient” (8). Symbolic reference requires an act of the percipient in order for it to occur. Thus the percipient is involved in creating his/her own experience.10

These, then, are the elements in the perception of a high-grade organism. Causal efficacy is the most basic element. It is the conformity of the spatio-temporal structure and the objects within that structure to one another. Presentational immediacy is a function only of higher-grade organisms. It is the mode in which objects appear given to consciousness. It is thus the mode that gives independence to actual entities, although these entities can never be truly independent because of their causal efficacy. Symbolic reference is the act of the percipient, which allows for symbolic meaning. These elements operate within consciousness, but they also exist metaphysically.

The Metaphysical and Epistemological Synthesis and Further Problems

Cassirer’s approach to the question of symbolic formation is grounded in epistemological analysis. Whitehead’s approach is metaphysical. Despite these differences, some aspects of their thought overlap. By combining these two theories, it may be possible to bridge the metaphysical gap between Cassirer’s expressive function and the representational function. We are attempting to discover what allows for this transition of meaning between the present existential situation to the independence of meaning and how this transition occurs. I proceed by first commenting on the overlaps and agreements in their theories. I will then comment about further problems that remain.

The first overlap is the parallel between what each believes to be the original or most primitive function. Cassirer’s expressive function is the original element in perception that comes in whole form in a perception. It gives an active character to the primitive worldview because the outerworld is seen as a “thou,” rather than as multiple “its.” Whitehead’s causal efficacy is the most primitive element in perception. It can be found both in higher and lower organisms. Causal efficacy gives the outer world to the percipient as active just as the expressive function.11 What the expressive function and causal efficacy do is give the world to us in an original, active view, a living efficacy.

The next area of agreement between Cassirer and Whitehead is in the parallel functions of represen-tation and symbolic reference. Representation is the relation between two spatially and/or temporally separate phenomena whereby one represents the other. Symbolic reference is the transference from meaning to symbol through an act of the percipient whereby one object in experience elicits the consciousness of another object in experience. The agreement seems to be in the definition of representation and symbolism, one object in experience stands for, or represents another. Whitehead gives the action of the percipient a name, symbolic reference. Although Cassirer does not give the action of the percipient a name, it is implied as part of the entire process.12

In order to abstract a part from the whole, and then to condense the whole into one of its parts, there must first be an objective view. One does not perceive parts or attributes unless one can see these not as a “thou,” but as a part of an object, something that can be separated, something that is not living, not active, but dead and independent. While Cassirer seems certain that such an act takes place, he does not provide a cause as to why we can view perceptions as objects. The furthest he ventures is to point to the development of language. Language is the aid by which we posit a permanence. The word forms a bond with the object, which we can hold in our minds as though the object were permanent. However, this ability of language presupposes the ability to see permanence. Words can only posit a permanence because we see words as already permanent.

Whitehead does provide an answer to this need for objectification or permanency. Presentational immediacy is that view by which we see the givenness of the world of objects which are actual in the same sense in which we are actual. If we translate this into Cassirer’s schema we find that the ability to use language in an objective way arises from the functioning of presentational immediacy. Presentational immediacy allows us to see the world as composed of objects, and if we have such an ability, then it would be possible for us to use language in an objective sense, which would ultimately result in the emergence of the representational function. However, we have simply moved the gap from being between the representational and expressive functions to being between the expressive function and presentational immediacy.

I believe that Cassirer was operating under a metaphysical understanding, but since it was outside of his developmental method, he did not write about it, at least in the first three volumes of The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms. There are, however, certain hints of his understanding throughout the text. In discussing Hegel’s Spirit, we catch a glimpse of Cassirer’s metaphysical grounding.13

In the posthumously published fourth volume of The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, Cassirer provides his metaphysical grounding in a discussion of life (Leben) and spirit (Geist). Cassirer identifies Leben as the base phenomenon, as the starting point for all theories. It is the action of Geist, however, that causes the building of the symbolic world. The nature of Leben is such that it continuously jumps over its boundaries. As this occurs, Leben destroys itself. It is Geist that preserves what Leben has accomplished (10-11, 219-20). In fact, Geist is the conduit to freedom for Cassirer, since without Geist the cultural world could not have been constructed.14

However, this explanation leaves unanswered the question of how we can progress from one stage to the next. How is it that Spirit and Life bring about a move from the expressive function to the representational function, or rather to the ability to perceive in the mode of presentational immediacy? While Whitehead has given us a metaphysics, it seems that we need something to set it in motion. This initial impetus may be found in the thought of Bergson.15

I shall show how by importing two ideas.16 The first is Bergson’s élan vital. Roughly translated it is “life force.”17 The work of the élan vital is creative evolution. It is the impetus to change, and to change in new ways. It basically inserts life into matter. The second idea in Bergson is durational moments. The durational moment is the amount of time that one can hold the same idea or perception before consciousness. 18

In humans it can last two to three seconds. I say humans because not all living things have the same durational moments; although everything does have some élan vital within, i.e., everything is alive. In fact it is this difference in the length of durational moments that shows the effect of the élan vital. In causing change and creative evolution the élan vital creates longer durational moments by inserting increasingly greater indeterminacy into matter.

How does consciousness move from this expressive view to a representational view? Whitehead answers that it is presentational immediacy, or an ability to see things as objects given to consciousness. Cassirer answers that the move is a selecting of objects from the sensuous flow, and then positing these objects as reference points in building up the representational structure.19 But neither of these answers is a real answer to the question; each is simply the identification of steps along the way. I suggest that we can explain how the progression occurs by using durational moments. As the élan vital creates entities with longer and longer durational moments, it gives nascent consciousness the power to hold something before the mind for longer and longer periods of time.20

When we have shorter durational moments we operate in the expressive world, with expressive space and expressive time. We can only apprehend or perceive what we are in contact with, i.e., the present existential situation. There is no abstract existence for expressive consciousness. What exists is only what exists in the present. There is no perception of permanence or impermanence. Rather, the present existential situation is the sole conveyor of the existence of past and future.

The move from a durational moment of one second to that of two to three seconds is a massive move, one that would result in very different orientations to the world.21 According to Bergson, the reason we can view an entity as an object is because it has a much shorter durational moment than we do. We cannot perceive these shorter durational moments, so the entity seems to be dead, and unchanging.22

As we evolved, gaining longer and longer durational moments, we gained the ability to see some entities as objects. Along with this ability we gained the ability to hold the object before the mind for longer and longer amounts of time. We could then select elements from the sensuous flow, hold them before the mind, and posit them as reference points. This is the origin of mental representations. It may have been this increase in the durational moments of humans that allowed us to gradually build up the representational world, and ultimately our current purely significative world, i.e., the world of concepts, in the fully abstract sense. Thus, the independence of the symbol from its original existential situation could have been caused by the development of increased durational moments in the human consciousness.

Notes

1 “We start . . . from the problems of the objective spirit, from the formations in which it consists and exists; however, we shall not stop with them as a mere fact; we shall attempt by means of reconstructive analysis to find our way back to their elementary presuppositions, the conditions of their possibility” (Symbolic Forms IV 57). At this point it is also necessary to explain what is meant by the objective spirit. The objective spirit is a Hegelian division of Geist. The objective spirit deals with the human culture. The influence of this idea is present in Marxism, for example. The objective spirit then is the movement of a people toward freedom as meant in the Hegelian sense. A tracing of the objective spirit would mean a tracing of the history of culture. The objective spirit also contains at every moment, that which has transpired before.

2 Cassirer distinguishes between scientific rationality and rationality in a broader sense. Scientific theories are only highly refined applications of the broader field of conscious functioning, but philosophical rationality requires an epistemological standpoint far broader than scientific reasoning can attain. Cassirer conceives human consciousness as the outcome of an extended biologico-cultural process. Thus, rationality from the epistemological standpoint is historical but not historicist. What distinguishes the historical from the historicist view is that the former emphasizes rational structure discernible in the present, analyzable as the outcome of an ordered process. Hence, it adopts a priori description and transcendental argumentation as its method. The historicist account would settle for narrative rationality and clearly Cassirer wants to do more than tell a story, even a good story.

3 We will not be discussing this function of consciousness in this paper since it lies beyond our present scope. However, whatever may be said of the transition from expressive to representational forms of consciousness will certainly have applications to the transition from representational to purely significative forms of consciousness.

4 Cassirer refers to this feature of consciousness as the “signal” in his later work: cf. “Essay” 22-23.

5 Cassirer argues against the traditional notions of sense perception which conflate perception and sensation by making the content of the perception the same as the content of the sensation. These theories make the simple sensation such as color the starting point, and then insert expression as an act of the mind. Perception, for these theories, is a conditioning force on reality. This means that nature is no longer being examined as is, but is instead being added to by the theoretical consciousness. This is precisely what Cassirer wants to avoid in searching for the development of consciousness, i.e., he wants to avoid a false starting point and post hoc theoretical interpretations of the starting point.

6 Cassirer draws upon the idea of First Universals in the work of Lotze for support of this account of the most rudimentary level of representation: cf. Symbolic Forms III 115-16, and Symbolic Forms I 281-82, and Lotze 22-24.

7 Unfortunately, it would take us too far afield to discuss in detail exactly what happens in this building up of the symbolic world; however, Von der Luft provides just such a detailed explanation.

8 For instance, consider the shifting meanings for a simple line. In the optical sphere, “A peculiar mood is expressed in the purely spatial determination: the up and down of the lines in space embraces an inner mobility, a dynamic rise and fall, a psychic life and being” (Symbolic Forms III 200). In the mathematical sphere the line “becomes a mere schema, a means of representing a universal geometrical law” (200). From the mythical sphere the line “is set up in order to make a separation between the two provinces [the sacred and the profane], and to warn and frighten, to bar the uninitiated from approaching or touching the sacred’” (201).

9 I again remind the reader that for Whitehead, objects are events. Thus the conformity expressed throughout this section in the nature of time is applicable to the conformity of one event to another. An actual entity both conforms to the world, and the world conforms to it. Causal efficacy, then, is a metaphysical fact, not merely a mode of perception. But in so far as it exists actual entities conform to it, and thus perception is a derivative of it. See Jorge Luis Nobo 351-52, for an account of this dual nature.

10 One might ask how this transference from symbol to meaning is possible. Whitehead’s answer is a structural intersection between presentational immediacy and causal efficacy. Interested readers should consult Machlachlan’s article.

11 “For the reality we apprehend is in its original form not a reality of a determinate world of things, originating apart from us; rather, it is the certainty of a living efficacy that we experience. Yet this access to reality is given us not by the datum of sensation but only in the original phenomenon of expression and expressive understanding. If an expressive meaning were not revealed to us in certain perceptive experiences, existence would remain silent for us. Reality could never be deduced from the mere experience of things if it were not in some way already contained and manifested in a very particular way, in expressive perception.” (Symbolic Forms III 73)

These words of Cassirer show the relation between the expressive function and causal efficacy.

12 The singling out of a part from the whole and then making it represent the whole seems to be inherently dependent upon action by the percipient.

13 A direct quote from Hegel is found at Symbolic Forms III 78 where Cassirer uses the objective spirit as evidence for the mutual existence of the expressive and representative functions. Cassirer has been characterized as a neo-Kantian by many: cf. Carl Hamburg and Klaus Oehler (217-19). However, recently support has been building to see Cassirer in a Hegelian light, especially with respect to The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms: cf. Donald Phillip Verene and John Michael Krois. I am more inclined to support the views of Verene and Krois, although the influence of Kant is undeniable.

14 This is probably too short a mention for those interested in the relation between freedom and the cultural world. Baeten provides an account of the relation between freedom and myth, which is part of the culture, according to Cassirer. Interested readers should consult her article as well as the second volume of Symbolic Forms for Cassirer’s description of the mythical world.

15 An anonymous referee of the paper made the following comment regarding the relation between Bergson and Whitehead with which I fully agree: in Process and Reality Whitehead brackets the phenomenological and experiential description of time and events for the sake of giving a systematic description of the most generic traits of existence. We do not get in Process and Reality an account of time as experienced by human consciousness except incidentally and illustratively; rather, we get a non-temporal description of temporality. Bergson’s project is exactly the other side of this coin—to find a language in which to describe the experience of time, and to construct an epistemology in which we can say we “know” what we are talking about. Unfortunately, both Bergson and Whitehead call these activities “metaphysics,” which greatly confuses the issue. In truth, Whitehead is doing systematic metaphysics of a synchronic and descriptive variety, while Bergson is doing phenomenological metaphysics of a diachronic and descriptive variety.

16 Bergson’s metaphysics, to my knowledge, has never been applied to the theory of concept formation or to the formation of symbols, but I am bringing it in here in full force. The work of the élan vital can easily be construed as the behavior of Cassirer’s Leben, and the creation of longer durational moments is the breaking through of the boundaries. However, for those not happy with the concept of Geist, what I develop here can be taken as an alternate account to the Geist-Leben dichotomy.

17 Bergson has a vitalist metaphysics. The effected synthesis in the symbol theories of Cassirer and Whitehead is achieved via this vitalist metaphysics. Susanne Langer has previously attempted to synthesize Cassirer and Whitehead, but she used a materialist metaphysics. This ultimately fails because of misplaced concreteness: cf. Randall Auxier’s “Langer.”

18 In explaining durational moments Pete Gunter writes: ‘‘‘Lived time,’ far from being made up of instants, is dynamic throughout. No two ‘segments’ of it—if there are segments—are identical; all differ qualitatively. And, far from being separate, successive states of consciousness merge into each other without sharp boundaries. Bergson calls this inner time ‘duration’ to distinguish it from mathematical time and to stress the fundamental endurance of each of its moments into the next” (269).

19 The example used by Cassirer was that of color. The reference points are blue, red, yellow, etc. They then form the boundaries or structure of what we call in totality, color.

20 In the fourth volume of Symbolic Forms, Cassirer refutes the theory of Bergson for its irrational elements and its overemphasis on the past to the detriment of the future (209-11). First, I think Cassirer’s account of Bergson is incorrect in its dealing with time: cf. Pete Gunter’s article, cited above, in which he argues against the traditional notion of irrationality in Bergson. Secondly, Cassirer need not have done away with experienced time. Experienced time, as I argue, is a possible mechanism to understand how consciousness develops. In short, Cassirer dumped too much of Bergson and left himself no way to explain how the progression of consciousness can occur.

21 A change in durational moment is a qualitative change rather than a mere quantitative change. Pete Gunter provides an excellent account of this in the aforementioned work. So, as Cassirer might say a change in durational experience is a change not of degree alone but of kind.

22 This notion appears to be taken up by Whitehead in his method of extensive abstraction (Auxier, “Influence” 316-17).

Works Cited

Auxier, Randall. “Susanne Langer on Symbols and Analogy: A Case of Misplaced Concreteness?” Process Studies 26 (1997): 86-106.

______. “Influence as Confluence: Bergson and Whitehead.” Process Studies 28 (1999): 301-38.

Baeten, Elizabeth M. “Myth and Freedom.” Thought 67 (1992): 324-38.

Cassirer, Ernst. The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms. 4 vols. Trans. Ralph Mannheim vols.1-3, and J .M. Krois, vol. 4. New Haven: Yale UP, 1953, 1955,1957, 1996.

______. An Essay on Man. New Haven: Yale UP, 1944.

Cooper, Ron L. “Heidegger and Whitehead on Lived-Time and Causality.” Journal of Speculative Philosophy 7 (1993): 298-312.

Gunter, Pete. “Bergson, Mathematics, and Creativity.” Process Studies 28 (1999): 268-88.

Hamburg, Carl. Symbol and Reality. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1956.

Krois, John Michael. Cassirer, Symbolic Forms and History. New Haven: Yale UP, 1987.

______. “Cassirer, Neo-Kantianism and Metaphysics.” Revue de Metaphysique et de Morale 4 (1992).

Lotze, Herman. Logic. Trans. B. Bosanquet. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1884.

Maclachlan D. L. C. “Whitehead’s Theory of Perception.” Process Studies 21 (1992): 227-30.

Nobo, Jorge Luis. Whitehead’s Metaphysics of Extension and Solidarity. New York: State U of New York P, 1986.

Oehler, Klaus. Sachen und Zeichen. Frankfurt am Main: V. Klostermann, 1995.

Verene, Donald Phillip. “Kant, Hegel, and Cassirer.” Journal of the History of Ideas 30 (1969).

Whitehead, Alfred North. Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect. New York: Fordham UP [sic: actually Macmillan], 1927.