AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From Contemporary American Philosophy, Second Series, J. E. Smith, ed., London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1970, 211-228.

Posted April 21, 2009

The Development of My Philosophy

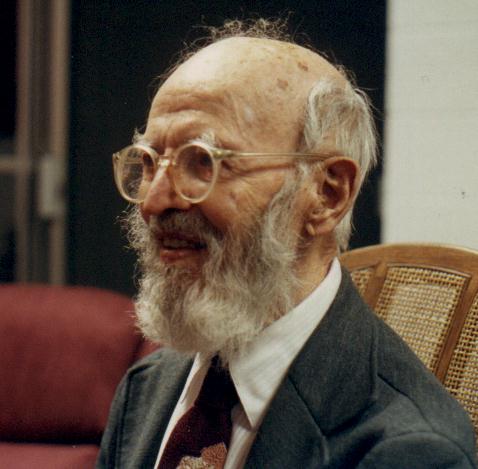

Charles Hartshorne

In my intellectual development, four principal periods may be distinguished. In the first (age 15-22, or 1912-19), the only philosophers in anything like the strict sense whom I can recall as having influenced me directly were the Quaker mystic and teacher, Rufus Jones (I had one course with him at Haverford College, where I studied for two years), Josiah Royce (solely as author of The Problem of Christianity), William James (The Varieties of Religious Experience), and Augus-tine (Confessions). Otherwise the chief stimuli during this period were Emerson’s Essays, Matthew Arnold’s Literature and Dogma, Coleridge’s Aids to Reflection, H. G. Wells’s novels Mr Britling Sees It Through and The Bishop, and Amiel’s Journal. I also read an encyclopedia article on Berkeley’s philoso-phy—which seemed to me rather silly, though some years later I enjoyed challenging people to refute it. Two years working as an orderly in an army base hospital in France gave considerable time for reflection. In spite of the limited philosophical fare, I reached (about 1918) some metaphysical convictions which I still see as sound—in part for the reasons which I then had in mind. The convic-tions reduce in a way to two.

The first is that experience (any possible experience) has an essentially social struc-ture, meaning by this that what is directly given as not oneself—or not simply one’s own sensations, feelings, or thoughts—is feeling which belongs to other selves, or more precisely, other sentient creatures. Besides one’s own feelings and sensations (and I thought then and think now that these are essentially akin), experience literally contains feelings belonging to other individuals. In short, I arrived on phenomenological grounds (not then so characterized) at the denial of the alleged truism: X cannot feel Y’s feelings. On the contrary—I have held for nearly fifty years now—X always feels feelings not X’s own, but those of other creatures. Of course, secondarily these feelings thereby become X’s, but not in the same simple sense as they were previously Y’s. In the language I learned many years later from Whitehead, experience is always “feeling of feeling,” where the first and the second feeling are distinct and involve at least two feeling subjects. The first feeling is X’s “subjective form” of feeling or “prehension,” the second is X’s “objective form” but Y’s subjective form. Thus experi-ence is essentially and literally and always in some degree sympathetic, a participation by one subject in the experience of other subjects. The concrete data of an experience are simply other experiences. These are not necessarily human experiences (except in immediate personal memory) or anything closely similar to the human. During my entire career I have rejected the assumption that psychical terms can refer only to animals. Rather, I found long ago that inorganic nature as experienced consists of non-human and non-animal feelings. That most people are not conscious of this has never seemed to me decisive. There is apparently almost no limit to the lack of consciousness which can be involved even in human experience. Here I agree in one way or another with Leibniz, Peirce, Whitehead, Wordsworth, Freud, the English psychologists Spearman and Aveling, etc. Moreover, the carelessly formulated, never really tested, psychological theory of “association” is ideally fitted to safeguard this unconsciousness. In my first book (1934), The Philosophy and Psychology of Sensation, I tried to argue on both a priori and empirical grounds for the essential identity of sensation and feeling, and for the social or participatory character of both. (But by that time I was in the third of the four periods above referred to.)

The other main conviction was that the social character of experience has a monistic aspect, in that the many selves, sentient creatures, or “wills” as I recall terming them, are somehow included in one supreme Will or purposive being. This belief, too, had a partly phenomenological basis. We experience a sympathetic overlapping of selves or experiencing subjects, in such a way that any attempt to derive all motivation from reference to long-run personal advantage, “self-interest,” is contradictory of the essential structure of experience. But if self-interest is not the motive, what is? To say that there is no one motive to which all others can be referred for their evaluation is to give up the quest for a rational theory. (In this respect the self-interest advocates are in the right.) Mere altruism is not the answer; for it commits us either to an indefinite multiplicity of interests, or else to an abstraction like the greatest happiness of the greatest number, a happiness which no one enjoys. The only satisfaction to further which can furnish a rational or all-inclusive aim is the satisfaction of an inclusive self, whose joy fully includes ours and that of all those about whom we could possibly care. In identifying with our fellows we do not lose our own self-identity, since we are all essentially expressions and constituents of the One All-inclusive Life. In this reasoning I was no doubt unconsciously influenced by Emerson and Royce; I was also treading, in my own way, a path taken ages before in India, China, Egypt, Greece, and Palestine. But it did not occur to me that the view implied, as it does for so many Hindus, that the plurality of selves is anything like an illusion. The many selves I took to be genuinely distinguishable from each other and from the inclusive self. Nor did it occur to me to suppose, with Royce, that what I will is also willed by the inclusive Being. My volition is in God, but not by God, it is in him not as his volition but as mine. I have never accepted the ultra-simple notion of “omnipotence” as sheer determination of events by a single agent.

For a time I did incline to accept James’s idea of a deity finite in power. Only much later did it become clear to me that there is no point in supposing that divine power falls short of some ideal of completeness. Rather, one must see that a monopoly of decision-making is not an ideal at all, and that the ability to manipulate puppets, or to make others’ decisions for them, is nothing very glorious, compared to the ability to inspire in others a creativity whereby their decisions transcend anything otherwise determined. To think this out was a matter of decades. I am glad, however, that my clergyman father never preached the conventional doctrine of omnipotence and always took for granted that many things happen not because God has decided that they shall, but because creatures decide as they do. In this my father was influenced by a liberal theological professor at the seminary where he studied. My gratitude to that professor! There was also, in my earliest form of natural theology, no inclination to identify God with an unmoved mover or with anything complete once for all, incapable of any sort of increase. I do not recall ever accepting this view, except for a short time while in Hocking’s metaphysics class, before he made clear to me the reasons for rejecting it.

The second period was four years of study (half of them as an undergraduate) at Har-vard, followed by two years of postdoctoral study abroad, mostly in Germany. My thesis on “The Unity of Being in the Divine or Absolute Good,” not a page of which has ever been published, was written during the fourth year at Harvard. It embodied a more qualified monism than the title might suggest, by no means identical with views like those of Bradley, Sankara, or Royce, since I not only, with Royce, asserted the reality of relations but unlike him accepted truly external as well as internal ones. To be sure, I agreed with the monists that every relation is internal to something, but I also held that it must not be internal to everything. I believed in genuine contingency or chance, and had been convinced by William James that God is not the only agent making decisions which can be attributed neither to any other agent nor to any complex of antecedent causal conditions. I thought then and think now that the deterministic theory of freedom is unacceptable, and this both for some of the reasons James gives and for still others. (I must by now have read fifty essays trying to reconcile determinism and freedom. They all miss the real problems.) Freedom is more than voluntariness; it is creation—and while aspects of a voluntary act, which is free in the sense of being unconstrained and consciously satisfactory to the agent, may be causally determined, the entire concrete experience must always have some aspects of creative self-determination, of causally optional “decision,” whereby the antecedent determin-ateness of the world is increased. Reality is in the making in the sense that causes are less determinate than effects, therefore less rich in value. This is the very point of causal production, without which, as James shrewdly saw, it has no point. Perhaps Bergson also helped me to see this. I had certainly at one time been a convinced determinist.

In writing the thesis, I was, so far as I know, uninfluenced by Peirce, and only slightly influenced by Whitehead, of whom I knew only what a hasty skimming of The Concept of Nature and an enthusiastic report by Northrop of his studies with Whitehead in London could teach me. I immediately accepted the view that the most concrete form of reality is the event. This seemed not to conflict with any conviction I had previously entertained. However, without the clarifications later introduced by Whitehead this was for me only a somewhat vague suggestion.

The two years abroad produced no very explicit new convictions, in spite of exposure to Husserl and other famous philosophers. Neither Husserl’s method nor his results seemed to me convincing. He was largely blind to the social structure of experience, as were the philosophers he took most seriously, e.g. Descartes, the English empiricists, Kant, Leibniz, and Brentano. Besides, Husserl had a naïve Cartesian confidence concerning the possibility of being absolutely clear and certain about phenomenological reports, whereas I thought that obstacles to such clarity and certainty are to some extent insuperable, and that, so far as they can be overcome, the way to do it is not through “bracketing the world” (which seems to amount to denying the intrinsically social character of experience) but in quite other ways—above all by trying out various logically possible formulations of what experience may be thought to be, looking to direct experience for illustrations. And one needs to be aware that the interest in direct experience is aesthetic rather than ethical, practical, or scientific. Husserl wanted to set aside speculations until pure and certain reports upon the given had been attained. I believed that there can be no wholly non-speculative descriptions of the given, somewhat as there is no such thing as mere assembling of facts prior to the formation of hypotheses in natural science. We start with beliefs. We cannot start with assumptionless description. This is the Baconian fallacy in phenomenology. All philosophizing is risky: cognitive security is for God, not for us. And Husserl was by no means without assumptions; for one thing, assumptions concerning the aesthetic aspect of experience, since he took for granted the usual view that value qualities are tertiary, mere reactions to the secondary sense qualities. I have denied this for nearly fifty years. I deny it now. Nothing is more primitive or pervasive in experience than intuitive valuation or feeling. Sensation is but a sharply localized aspect of this. Later I found this view in Whitehead, Bosanquet, Croce, and others.

The third period began abruptly in September, 1925, when I became a humble member of the Harvard philosophy staff, and was asked at one and the same time to begin editing the writings of C. S. Peirce and to assist Whitehead in grading papers. Thus I was simultaneously exposed to intensive influence from two great minds, one (Peirce) of whom had been hitherto almost unknown to me and the other only slightly better known. Both philosophers immediately appealed to me more than any third, except perhaps Plato, had previously done. Where Husserl, Heideg-ger, Kroner, Ebbinghaus, Rickert, Hartmann, Natorp, and before that my Harvard teachers, taken singly, had seemed to offer somewhat thin philosophical fare, Peirce and Whitehead were to my understanding thinkers who combined great technical competence with a rich, subtle sense of reality in its manifold aspects, and extraordinary power of intellec-tual invention. They were obviously aware of the social structure of experience and reality and also of its monistic aspect; and they seemed less naive than Husserl about the method of philosophy. They had a matchless sense of the range of human concerns. They were humorous as well as deeply serious; and Whitehead at least (unlike some of the pro-fessors I met abroad) was almost miraculously free from vanity. On the other hand, Peirce of the two was more adequately aware of the nature of science on its empirical side. For example, Peirce was a pioneer in affirming the importance of behaviourism in psychology. (Here Whitehead was amazingly aloof from science in its working procedures.) Yet Peirce was as convinced as Whitehead that the reality of the world is in feelings, not in mere matter. I cannot but regard the simultaneous exposure to two such philoso-pher-scientists as a wonderful stroke of luck. That it came after I had had opportunity to face the problems of philosophy for nearly ten years, and had had the benefit of more than a dozen skilful teachers of the subject, was probably all the better.

An additional piece of good fortune was that after a year or so of my solitary struggling with the Peirce papers, Paul Weiss volunteered to help. Thus a job too big for one man became manageable. I shudder to think of having had to do it single-handed. Weiss was just the person the situation called for.

During the three years as instructor and research fellow at Harvard, and for some years thereafter, I considered myself as both a “Peircean” and a “Whiteheadian,” in each case with reservations. It would be only a guess if I were to say now which influence was the stronger. My partial acceptance of Peirce I can see to have been in some respects uncritical, particularly with respect to his Synechism. As to Whitehead, I never could assimilate his notion of “eternal objects,” and for a good many years I rejected entirely his doctrine that contemporary events are mutually independent. On the last point I have come to change my mind, but to make up for this have become more aware of difficulties in other parts of his system. It does not seem so very important that one encounters some philosophers in the flesh and others not. If Peirce has perhaps influenced me less than Whitehead, it is chiefly because his writings are on the whole less congenial to the philosophical attitude I already had when I encountered the work of the two thinkers. And after all, I learned Whitehead’s philosophy chiefly from his books, as I did previously that of Emerson, James, and Royce—three men without whom I cannot imagine my intellectual development.

A good part of the effect of Peirce and Whitehead was to encourage beliefs already adopted, such as the self-creative character of experience, implicative of real chance; the ultimate dispensability of non-physical categories (the emptiness of the notion of mere matter); the two-aspect view of God (which I got from Hocking if from anyone) as both eternal and yet in process (hinted at by Peirce, asserted by Whitehead—or as both absolute and relative, infinite and finite; the necessity for admitting internal as well as external relations between events; the immediate givenness (“prehension”) of con-crete realities other than one’s own experi-encings (I had been confirmed in this by reading Lossky); the priority of the aesthetic aspect of experience (perhaps due to Wordsworth more than to any philosopher, but confirmed by Rickert and Heidegger and later by Croce and others, including some psycho-logists).

While doing the Peirce I began to write the book on sensation. This led me in time to intensive study of psychological monographs and journals. This exploration of an empirical science was enjoyable. With the publication of the book, however, I largely dropped this line of study, and to this day have not been able to make much further advance in it. I came to understand why psychologists in general found this book little to their liking. On the other hand, like some psychologists, I believe it embodies insights which must sooner or later be incorporated into science as well as philosophy. With the sensation book (a development of one theme of my thesis), as well as the Peirce editing, out of the way I began to work out my version of metaphysics and natural theology, the central theme of the thesis. But now I had to try to incorporate what I had learned from Peirce and Whitehead, also what I was learning at the University of Chicago by association with pragmatists and positivists, including many scientific friends with positivistic leanings. (For twenty-seven years I listened to papers by members of the “X Club,” an association of scientists, and came to know some of the members rather well.)

Since I was teaching about Peirce and Whitehead, as well as attempting to present my own views, my thinking and writing fluctuated between exposition and, to some extent, defence of the views of these men and the effort to build my own system indepen-dently. Probably my contemporaries found themselves a bit puzzled as to how to classify me. Was I essentially a disciple of Whitehead, secondarily of Peirce? Or was I essentially what Husserl suggested I would be, an “independent philosopher”? In my thesis and in Germany I did not think of myself as a disciple of anyone, nor so far as I know did anyone else. True, I was perhaps closer to Hocking, among my teachers, than to the others, but Lewis, Perry, and Sheffer had had strong influence, and so had the writings of Russell, Moore, Bergson, Bradley (in good part by way of disagreement), and even Spinoza. But from 1928 to, say, 1945, it was plausible to think of me as Peirce’s and even more as “Whitehead’s disciple. (Some even imagined I had been enrolled as a pupil in Whitehead’s classes.) If, however, I have often defended Whitehead, and also Peirce—especially before Whitehead’s Adventures of Ideas had rounded out that writer’s great speculative period—and have indulged in one-sided or exaggerated praise of their philosophies it was partly because of the conviction that anyone taking the systems of these famous and eloquent writers seriously would at least be in the general neighbourhood of basic metaphysical truth, which would not equally hold, in my judgment, of those taking Moore, Hume, Hegel, Russell, Ayer, Bradley, Wittgenstein, Austin, Ryle, Dewey, Lewis, and Carnap seriously.

It seemed obvious that truths so ultimate that they hold of all possible realities can have no necessary connection with anyone human being, whether Whitehead, say, or myself. Without claiming to have been free from egoistic cravings, I can perhaps claim to have had a genuine and persistent ambition to enrich human consciousness, an ambition strong enough to make me at least partially indifferent to the question of who is credited with discovering certain conceptual means for appropriating the truth. Once in Germany (1949) a professor complimented me upon a speech concerning Whitehead’s philosophy and added something like the following: “The modesty with which you avoided stressing your own views as distinct from Whitehead’s made your talk all the more appealing.” I wish to add to this some remarks overheard from students:

A. “What is Hartshorne teaching this quarter?”

B. “Whatever it is, it will be Whitehead.”

C. “Whatever it is, it will be Hartshorne.”

D. “The trouble with Hartshorne is, he’s so damned original.”

Of my former students, one, John Cobb, is an important young theologian whose book, A Christian Natural Theology Based upon the Philosophy of Whitehead, is perhaps the best critical outline of Whitehead’s system we have. Another, Schubert Ogden, is an impor-tant young theologian whose philosophical base is my philosophy. He is one of a number who will see to it that my ideas will not be forgotten—no matter what happens to me personally. I am not greatly excited by the difference between these two, but proud of them both. For either way the “Neoclassical” tradition, the natural theology of creative becoming and divine relativity, will persist.

The change to what I term my fourth period, one of greater independence, or greater stress upon my own intellectual devices and spiritual convictions, was gradual. The sharpest shift probably occurred in 1958 while I was in Japan. Here by request I taught my own views, not Peirce’s or Whitehead’s. And here I began to think out with a new thoroughness the conviction expressed in my thesis (a conviction scarcely hinted at by Peirce, and not even hinted at by Whitehead or my Harvard teachers), that Anselm’s ontological argument is one of the most truly essential discoveries ever made in meta-physics, even though a discovery which, like so many others, was partly misinterpreted by the man who made it, as well as by most of his critics. This line of inquiry is carried almost as far as I am likely to carry it in Anselm’s Discovery, together with Chapter Two of The Logic of Perfection.

It has seemed more and more clear to me that both Peirce and Whitehead tend to blur the important distinction between meta-physics, or a priori ontology, and empirical cosmology, the latter subject but not the former making essential appeal to empirical evidences. The distinction can be found in both men, but inadequately emphasized and clarified. The clue to a more adequate way of dividing the a priori and empirical elements in philosophy is provided by Popper’s great theme of observational falsification as the decisive feature of empirical knowledge. Not “Could it be verified?” but “Could it conceivably be falsified?” (by observation) is the primary question to ask if one wants to classify statements as belonging to science or merely to philosophy. I define metaphysics, or a priori ontology, as the search for truths which, though “about reality,” could not conflict with any conceivable observation.

The dogma that if no experience would count against a statement it “says nothing about reality” is, to me, just anti-metaphysics posing as self-evident. I think, on the contrary, that there are statements true of reality which no observation could conceivable falsify. For example, “Deity (defined as the property of being unsurpassable by another) exists” conflicts with no conceivable observa-tion, yet implies this, for instance, about reality: that it is completely known to the being who could not conceivably be surpassed by another. That this statement cannot conflict with any conceivable observation is deducible from “unsurpassable by another,” as I have shown in various writings. I also take the statement, “Every event includes properties not deducible from its causal conditions and the valid laws applicable to these, but yet every event has some features thus deducible,” to be true of reality as such, while again conflicting with no conceivable observation.

Of course, a statement which no observation could count against says nothing contingent about reality. It does not discriminate one possible world state from another. This does not prevent it from being true of any and every such state, hence also (trivially if you like) of the actual state. Thus if the divine existence is necessary, as I hold, then no possible experience could negate it. It is therefore trivially true that it fits our actual experiences, and it is true of the actual world that it is divinely known. “Trivially” here means, “as anyone who fully understood the terms of the problem would see to be self-evident”.

It is a strange logical lapse to infer “describes no possible experience” from “conflicts with no possible experience.” What could not be false under any circumstances is either nonsense or it is true under any and every circumstance. The notion that the “non-existence of deity,” or existence either of an “absolute causal order” or of a “cause-less chaos,” must describe a conceivable circumstance or “state of affairs” is just the assumption that neither theism nor the idea of creative or indeterministic causality is metaphysically valid. If we ask how this invalidity is known, I think we must answer, “In no way.” Rather, we have sheer assumption. The “non-existence of deity” is, of course, a possible verbal formula, as is “the existence of pure chaos” or “an absolutely deterministic causal order”; but every attempt to provide consistent and unmistakable significance for the formulae will, I think, fail. We can conceive a world resting upon and known to divine power, but only in a fashion applicable to any conceivably observed world as well as to ours. No observational criterion for separating divinely ordered and known worlds from those not so ordered and known is conceivable. If you doubt this, tell me the criterion. The very idea of God itself implies the impossibility of such a distinction. “Dependent upon God,” like “creative yet cau-sally conditioned,” is a metaphysical expres-sion, definitive of possible experience in general, neutral between alternative forms of experience.

Theism, Creationist Causalism, are true of reality, but not empirically true. They are descriptions of reality which are neutral to alternatives other than verbal. Of what use are they, some will I ask, since the alternative in such a case is only verbal absurdity or vacuity? Answer, of no use to anyone whose understanding is superhumanly penetrating enough to grasp immediately and surely the absence of a real alternative, but quite useful to confused human beings (that is, all of us) easily able to confuse sense and nonsense. Metaphysical truths are truistic—if one is sufficiently clear-headed enough to see them as such. But who is? Wisdom’s disjunction concerning metaphysics, “paradox or platitude,” would be applicable perhaps to an angelic intelligence. But for ours there is a third possibility, termed by an Indian philoso-pher (J. N. Chubb) “luminous tautology,” evident when and so far as we grasp the meanings of terms which express features too profound to be humanly apprehended without difficulty. Of course God exists for you, if you understand “God.” But why should that understanding be altogether easy, or exempt from danger of confusion or subtly hidden contradiction? Perhaps “God” cannot be understood, having only a noncognitive or essentially confused import, a vague associ-ation of pictures incapable of being definitely true or false. But if this positivistic tenet is rejected then theism becomes obligatory. For “deity can be conceived not to exist” is demonstrably confused or self-contradictory.

Apart from my stress on the a priori status of metaphysics and upon the ontological argument, I have various differences from Peirce and Whitehead. Some of these are rather additions than rejections. I make great use of the idea of asymmetrical relativity, and of asymmetry as a logical concept, in a way that seems to have no precedent in the history of philosophy. Here Peirce (especially in his account of secondness) was partly mistaken, and Whitehead, though correct, failed to make the point explicit. I believe that all philosophers have in this respect neglected a powerful key to metaphysical truth. But I have yet to publish an account of this line of reasoning.

Whitehead’s “eternal objects” in my opinion fail to do justice to the force of nominalistic arguments. Here I find Peirce’s view of the continuum of possible qualities, and of continuity as a merely potential rather than actual “multitude” (or set), a superior line of thought. This doctrine was one aspect of what Peirce called Synechism. In this aspect, Synechism coincided with a view of qualities which I had worked out partly in my thesis and partly during the two years preceding my work on Peirce. This is one example of the pre-established harmony by which, from 1925 on, I found myself related to Peirce and Whitehead.

The other aspect of Synechism puts Whitehead in definite opposition to Peirce. Here I have long followed Whitehead, and at this point particularly I am indeed his “disciple,” for without his influence I might never have felt the force of the reasons favouring his quantum principle of unit instances of becoming which are neither instantaneous nor do they involve real internal succession, in spite of his dubious talk of “earlier” and “later phases.” Where Peirce thought present experience was “infinitesi-mal” in time length, Bergson and Dewey are vague or ambiguous on the issue, but Whitehead opts for a definite succession of unit events, never more than finite in number in a finite time. There is, in short, no continuity of becoming. (This has nothing to do with the Humian notion of a mere succession of events without intrinsic connectedness or partial identity. Confusing these two vastly different ideas is a common error in the criticism of Whitehead.) A continuum has no definite finite number of segments, but a stretch of actual becoming always has such a number, according to Whitehead. The mathematical continuity of time, as of space, refers to time as order of possible, not of actual, happenings. Peirce confuses the two orders: exactly the mistake he ought not to have made, since he himself holds that continuity is the order of possibilities. To make it also the order of actualities is to abolish any clear distinction between actuality and possibility. Moreover, this denial of objective modal distinctions is a clear case of what Peirce attacked as “nominalism.” The penalty was that whereas he ought to have anticipated quantum mechanics in principle, Peirce in effect rejected it in advance. Yet to furnish a guide to the development of physics was one of his declared objectives.

Another point that is obscure in Peirce, and also in my thought prior to studying Whitehead, is the temporal structure of perception. Is the directly experienced always—or even ever—simultaneous with the experiencing? In short-run memory—here Peirce and Whitehead agree, and I think I might in any case have held previous experiences are directly given (in spite of the “mistakes of memory,” really of memory judgments). But only Whitehead states clearly that the given is no less temporally prior in perception than in memory. It was, I think, a flash of genius in Whitehead to generalize the element of immediate given-ness—“prehension,” a word used by Leibniz, incidentally—so that the given is always temporally antecedent to the prehending experience. This solves at one stroke a host of metaphysical problems. Perception and memory on this assumption have the same relation to time, both giving us the past, immediate or remote, but whereas memory gives us our own personal past, perception gives us the impersonal past, the past of other individuals, including those individuals constituting our own bodies. In both cases, by a natural and pragmatically harmless illusion, we may seem to ourselves to be experiencing the very present. In the case of memory the illusion is called introspection—really very short-run retrospection. Some other philoso-phers have avoided this form of the illusion but nearly all have fallen into it in interpreting perception. I know of no philosopher before Whitehead in East or West who viewed with complete clarity all immediate experience of the concrete as experience of past happen-ings. I do not believe I could have seen this clearly without help from him. And, unless it is seen, the asymmetry of awareness, its one-way dependence upon its objects, cannot be clearly grasped. The concept of prehension as the basic form of dependence, the link between successive moments of process which Hume could not find, is a contribution second to none in modern metaphysics. It presupposes the concept of actual becoming as discontinuous; for without this concept the issue tends to remain incurably obscure, as Peirce’s example nicely shows. The temporal structure of his Secondness or Reaction, and indeed its logical structure—is it symmetrical interdependence or one-way dependence?—is never made clear, with all Peirce’s wrestling with the subject. It could not be clear, for in sheer continuity there are no definite units, whether objects or subjects, to act or to interact.

Both Peirce and Whitehead have affirma-tive things to say about God. The one hesitantly and inconsistently, the other more definitely and coherently, posits a divine Becoming rather than mere Being—an idea which duplicated a conviction I had acquired from Hocking’s metaphysics class about 1921. But even Whitehead seems partly inconsistent on the issue (in speaking of God as an actual entity rather than a personally ordered society of entities, also in sometimes speaking as though God were simply “nonntemporal,” and in still other ways), so that it is in my opinion impossible to accept his exposition of this theme as it stands.

I agree precisely with Chubb’s contention that the idea of God, fully developed, is the entire content of non-empirical knowledge (including arithmetic and formal logic). Neither Peirce nor Whitehead say this with any explicitness; there is nothing in metaphysics (or a priori knowledge) not also in natural theology. They are essentially the same. A non-theistic metaphysics—as Comte held—is a confused and arbitrarily truncated natural theology. If I have concentrated upon natural theology more, probably, than any other recent writer, it is partly because I learned long ago from Plato, Spinoza, and Royce, that this subject coincides with metaphysics, and partly because I was shocked at the carelessness with which, as it seemed to me, the subject of “God” was being treated by my philosophical, and to some extent theological, contemporaries. It has seemed clear that unless I took pains to work out certain things in this connection no one else was likely to do so in the near future. It was for the same reason that I wrote the book on sensation. No one else was doing much (by my standards) with either topic. Many good minds were grappling with philosophy of science, formal logic, ethics, perception, even aesthetics, but the two neglected mysteries, sensation as such and deity, seemed to demand an attention far beyond what anyone with adequate training was giving them. In both cases there was a vacuum into which my interest almost automatically moved. That as a result I might gain a wider circle of readers than philosophers alone, and, for instance, become an influence in contemporary theology and religion, was not, I think, particularly foreseen and did not furnish the main motive. Nor did mere religious feeling or piety. What I thought I saw was an intellectual mess needing clarification.

It is a question of some moment how far a philosopher, even one rather young, can be induced by another to change his opinions. Hocking did convince me in a very brief discussion, but once for all, that my perhaps only momentary toying with the idea of an immobile deity, devoid of an open future, was a mistake. Whitehead did convince me that the becoming of experience and of reality generally is in quanta, in unit cases which correspond to finite stretches of time, not to instants. He did convince me, when I was no longer very young and he was no longer alive, that contemporary events are mutually independent, and that perception gives only antecedent happenings. Peirce did convince me, backed up by Dewey and Mead, if I needed any convincing, that nameable qualities such as colours are not eternal but emergent. Moore did convince me, again if I needed convincing, that it cannot be correct to say that an experience can be its own object, that the data of mental states can be those very states. (Here Russell is wrong, Berkeley at best ambiguous, and Moore right.) Hocking or James convinced me that determinism, which I had for a time strongly affirmed, was an error. Later confirmation came from Peirce, Whitehead, and Popper. Influences I cannot trace led me to give up the belief I held for a time in my twenties in personal immor-tality (apart from Whitehead’s “Objective Im-mortality, of all events).

Many influences convinced me that “proving” the rightness of a philosophical position was much more difficult than I still hoped, even in my early teaching days, and that having a right to be confident of one’s views was much more problematic. At the least one must be able to state the counter-arguments in as close to their strongest form as possible. The basic giveaway in philoso-phy, apart from the ignoring of opposed positions, is the straw-man argument systematically resorted to. I know a philosopher, a former fellow student of mine, who told me not many years ago that in his courses the students read only the textbooks of which he is the author. How then, I asked him, do they learn about other views than yours? “Oh,” he replied, with every assurance, “the other views are all in my books.” This is not (I trust I can say) how my students are treated. And I have tried to argue with able opponents, not just with sympathizers or callow, obsequious, or cowed students. To this extent, at least, any confidence of rightness I feel has some justification. Although I have written over sixty reviews, no one, whether author or another reader, has accused me of misrepresenting the views expressed in the book which I have reviewed. There is a reason for this. After writing the review I have taken pains to go over the criticisms (and usually I did disagree at some points with the author), looking up once more the passages to which my review took exception to see whether they really did express the views I found objectionable. Usually they did, but now and then they did not, so that I had to delete or alter the criticism. I wonder if this rule is generally followed. If not, that alone is enough to account for many of the misrepre-sentations which disfigure the journals. My own books have sometimes suffered from this insufficient care to avoid the straw-man procedure in the one place where, if anywhere, it is inexcusable, in reviews. One’s memory of passages one has an inclination to dislike is particularly apt to be creative in an unwittingly malicious fashion. Only careful rechecking can be relied upon in such cases.

The disciples of Wittgenstein have taught me at least something. I have lately been coming to see that my criticisms of “classical theism” and “classical pantheism” (technical terms which I have tried to define with care) are really in substantial degree linguistic, and amount to accusing the partisans of these doctrines of employing words taken from ordinary meaning (or significantly related to words that are so taken) to express esoteric meanings whose relation to the ordinary meanings has never, and really never, been carefully set forth. I refer to “absolute,” “relative,” “infinite,” “finite,” “ultimate,” “transcendent,” “immanent,” “perfect,” “real,” “omnipotent,” “omniscient,” “neces-sary being.” These terms, I hold, have been systematically misused almost throughout the history of metaphysics, Occidental and Oriental. I deny that this is inherent in the metaphysical use of words as I define that use. One can be careful; but for whatever reasons metaphysicians have usually not been.

If I have any regrets about the develop-ment sketched above they are two. First, I might have taken more seriously than I did James Haughton Woods’s wise injunction: “Study logic; it is the coming thing in philosophy.” I took it somewhat seriously and learned a good deal from Lewis and Sheffer, but I might well have gone further, and have kept up the habit of thinking in mathematical ways better than I have. Second, I would have done well to make my writings more readable than I sometimes have. Style is important in philosophy. The extraordinary influence of some recent English writers not only in England but in the United States and many other countries is owing in no small measure to their readability. Clumsy sentences are resented, sometimes uncon-sciously, and neat or witty sentences are enjoyed and promote a good opinion of the thought as well as of the writing.

Apart from these two points I am tolerably well pleased with the way my career has gone. Unfortunately, there seems no way in philosophy to escape altogether from the dilemma: either remain in a state of uncertainty about the basic correctness of your position, or else protect yourself from exposure to hostile views. I do not find in the usual varieties of “linguistic analysis” much to arouse doubt concerning my essential tenets or methods, but I am less easy when confronted with the contentions of “finitistic” logicians concerning the vacuity of the notion of infinity, apart from the merely potential infinity of “for ever more and more.” On the one hand, with G. E. Moore, I do not see that we can dispense with an actual infinity of past events, but on the other hand I feel the force of neo-Kantian objections to such an infinity. My guess at present is that this is merely a particularly clear-cut form of the basic mystery of metaphysics, as the exploration of luminous tautologies, truths that would be self-evident if we could grasp them with sufficient clearness, but which cannot human-ly be grasped quite in this fashion. Will mathematicians ever come to agree concerning infinity? Perhaps no more than philosophers can agree concerning God. And if we cannot agree, can any of us have the right to be sure? There is one way in which, on “neo-classical grounds,” one can soften the dilemma, “numerically finite or numerically infinite” with respect to past events. The entire value of reality is exhausted in the qualitative richness by which harmony of feeling in God is intensified. Granted an infinity of past events, all but the most recent events are already synthesized in the divine receptivity. They thus form a single though infinitely complex feeling. If reality is finite in space, as I take it to be, then only a finite number of items needs to be synthesized in any given case. Thus in a sense no “infinite synthesis” is in question. Does this solve the problem? Perhaps.

I feel moved to express immense gratitude, first to my philosophical teachers at Harvard, 1919-23, who presented a wonder-fully sharp and invigorating challenge by the intensity and diversity of their intellectual and spiritual values: J. H. Woods (the scholar in Indian philosophy), Demos, Eaton, Perry, Hocking, Lewis, Sheffer, Bell (who left philosophy for gentleman farming in Nova Scotia, but whose insight into modern philosophy was remarkable), Levy-Bruhl, De Wulfe; also the psychologists Troland (that superb prematurely deceased scientist), Langfeld, and McDougal. Second, my gratitude goes to the group of scholars and thinkers who taught me as a post-doctoral student at the University of Freiburg 1923-5: Husserl, Becker, Heidegger (I heard him also in Marburg), Kroner, and Jonas Cohn. Third, to Peirce and Whitehead, two men who sought truth incomparably more than success or popularity, and who in inborn genius have perhaps never been surpassed. From Tillich and Karl Popper I have also learned, and to Berdyaev and Paul Weiss I owe at least the encouragement of their sturdy independence and vividness in the exploration of metaphy-sical issues. These, with Rufus Jones, after my intelligent and intellectually honest preacher-father, are the persons who have chiefly taught me (if anything has) to think philosophically, or to react creatively to the history of ideas.

Once when in Paris I told Levy-Bruhl that my interest was in metaphysics he replied, “I believe, with David Hume, that our line is too short to sound such depths. However [he graciously added] it is an honour to try.” Have I succeeded in sounding the metaphysical depths? I only know that I have tried, and have usually, though not perhaps always, felt that it was a privilege to do so.