AnthonyFlood.com

Where one man sorts out his thoughts in public

From The Journal of Philosophy, 43:21, October 10, 1946, 573-82. How far is Harts-horne's identification of reality with what God (the ideal knower) knows from Lonergan's identification of the real with being, being with complete intelligibility, complete intelligibility with the content of an unrestricted act of understanding, and that act with God?

Posted November 11, 2008

Ideal Knowledge Defines Reality: What Was True in “Idealism”

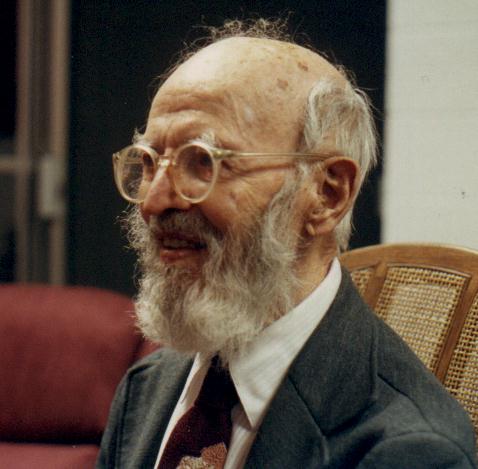

Charles Hartshorne

I wish to summarize the argument in advance. Imperfect knowledge, such as ours, seems to imply a non-coincidence of things as known and things as they are, of “reality” and known reality. Yet reality, so far as simply not known, is useless as a standard of knowledge. The standard must be furnished by internal characteristics of knowledge, such as consistency, clarity, certainty. The ideal of these qualities gives the definition of “perfect” knowledge. This definition does not presuppose “reality” as a standard, hence it can, without circularity, provide a definition of reality. This definition is: “the real is whatever is content of knowledge ideally clear and certain.” Knowing reality, or knowing things as they are, then becomes knowing that is in conformity with ideal knowing; or, whose objects as known coincide with the contents of ideal knowing. The truth of “idealism,” thus formulated, has been obscured hitherto by some invalid, but commonly alleged, corollaries, such as that ideal knowledge must be timeless, without contingency, passivity, or probability; that it must enjoy all possible satisfaction and value as actual; that its objects are “inert” ideas (Berkeley), rather than self-active and concrete individuals; that all coherent ideas are true; that the idealist must argue from an “ego-centric predica-ment.” These and other misunderstandings must be cleared away before the doctrine can be evaluated objectively. So far, the summary.

We human beings know that there are many things which we do not know, that “reality” is more extensive than our knowledge. But it seems that, in this comparison, both terms must somehow become known. How can one step outside the circle of one’s knowledge in order to see that this “outside” is a larger circle?

Part of the answer is easy to give. We find inconsistencies and reversals in our opinions, and also vagueness, uncertainty, doubt. Our beliefs can be true only if there is something determinate which we do believe; and so far as there is contradiction, vagueness, and uncertainty in our beliefs they lack something as beliefs. Thus we may surmise that the distinction between what we know and reality expresses an awareness of the possibility (or actuality) of beliefs more perfect than ours. We are contrasting the content of our half-beliefs with what would be (or perhaps is) the content of beliefs ideally clear, consistent, and certain. When we say, we need further empirical evidence, we are saying, we need the materials for more perfect belief. “Seeing is believing,” and it is more unadulterated believing than any acceptance of indirect testimony. Certainty free from qualification is possible only if the thing itself is directly and clearly present to us with the character we impute to it. In so far as it is thus present, we can not doubt it—otherwise doubt is always possible, even though this potential doubt, which is actual uncertainty, may be repressed below the level of consciousness.

We may, if we wish, restrict the word “belief” to those gradations of taking-for-true which fall short of complete evidence and complete certainty, i.e., absolute knowledge. Nevertheless, such complete evidence and certainty remain the ideal of all the gradations. (Probability is not excluded from the ideal, provided probability is something objective—for example, a frequency, which can be certainly apprehended by some conceivable mind.) Now it is this ideal belief or knowledge which defines “reality,” and herein, I think, is a great discovery of “idealistic” philosophy. The imperfections of human knowledge can be stated without comparing the known with the “real”; but not without comparing, at least implicitly, defective with perfect knowledge.

Unfortunately, the classic definition of perfect knowledge as “omniscience,” or knowledge of all things, seems to imply a prior reference to all existence or reality, as the standard by which the meaning of cognitive perfection is to be identified. But this difficulty is easily avoided by speaking rather of knowledge ideally consistent, clear, and certain. “The content of ideal knowledge,” thus defined, will furnish the definition of reality. It is not that the ideal knower (whom I shall call God) knows all things, but that the phrase “all things” simply means whatever the ideal knower knows. And this ideality consists (to repeat) in internal characteristics like certainty, not in a relation external to God between things “as they are” and as they appear to God. Rather, “things as they are” is merely a verbal alternative for “contents of the ideal knowledge.” After all, when we human beings use the phrase “all things,” or “the universe,” we can mean nothing unless, in some vague way, even we are aware of all things. Now a clear version of such awareness would have reality itself as simply its own content. Thus reality, as additional to knowledge and its contents, is superfluous; but a knowledge ideally related to its contents is necessary. Such is the thesis of this paper.

I wish above all to remove certain misunderstandings of the thesis, misunder-standings for which idealists themselves were largely responsible, and through which their discovery has been sadly obscured.

(1) First misunderstanding. Ideal know-ledge, definitive of reality, is not knowledge “from the standpoint of eternity.” To so regard it is a natural but fatal error. Our human knowledge is not made imperfect by the fact that we do not know all events “in a single now,” nor yet as links in a chain of necessities. Since certainty is the presence of what is meant, it would be a contradiction for the future, in its detailed completeness, to be a matter of present certainty. It is tempting to reply, Ah, but events which we call future may to ideal knowledge be neither present nor future in the temporal sense, but eternally present. The temptation is to be resisted. Whatever is content of an eternal or immutable knowledge is itself eternal and immutable; for if any item in a system changes, the system is not unchanged. Moreover, we (and even more so, God) are agents as well as spectators, and if the how of our future actions existed now or eternally, then we should have no freedom as to this how, and the idea of creation as the contingent actualization of potency would be meaningless for us. Freedom consists in present indeterminacy as to future action, and if ideal knowledge excludes such indeter-minacy, then God can have no freedom, and must be less creative than we seem to be. On this path arise numerous absurdities and contradictions by which theology has been brought into shameful discredit. (Royce’s great failure resulted chiefly from this cause.) Our imperfection in knowledge of the future lies, not in its leaving details unspecified, but in its failure to exhibit clearly how far and in what respects the future is determinate and how far indeterminate. For, of course, it is far from completely indeterminate, since that would be chaos, and would destroy all difference between near and remote futures, and, therefore, any idea of temporal order. Ideal knowledge would see, with absolute certainty, how far the future is limited in its potentialities, while yet free within these limits. (As previously stated, probability so far as objective or belonging to the content of knowledge, and therefore itself certainly and clearly knowable, is not excluded from ideal knowledge.) Would then God be in doubt what to believe concerning the future? On the contrary, he would know without doubt how far belief is in order and how far there is nothing to believe, since there is no determinate object or content. Details of the future are for the future, not for the present. Infinitely less are they for eternity. This God would know and be quite clear about.

The familiar argument that perfect knowledge can learn nothing new is ambiguous. Perfect knowledge learns nothing new about what is already determinate; but it comes to know new facts as new determinate objects come into being, i.e., come before it as contents. Fully determinate is only the past, down to the present. As Peirce said, the past is the sum of accomplished facts: time is objective modality, the union of the actual past with the potential future. I have shown elsewhere that there is no contradiction in supposing details of the past to be fully clear in present awareness, since past in the temporal sense can be defined without any implication of absence from present awareness or present actuality, whereas future can not be thus defined. I have also shown that the doctrine is compatible with the law of excluded middle regarding truth values, and with the identical proposition, What will be will be. The future is not simply what will-be, but also what may-or-may-not-be. It is the objectively vague—that whose degree of indefiniteness is, to ideal knowledge, definitely given.

(2) Second misunderstanding. Ideal know-ledge does not mean ideal fulfilment of all desires, actualization of all possible values, or any other ground of unlimited optimism. There are inconsistent desires and incompatible possibilities of value, and it was only by a non-sequitur that idealists identified the cognitive ideal with the general ideal of values. To know all individually determinate, that is, non-future, facts, and all future possibilities as possibilities, is by no means to enjoy all possible satisfactions. The merely cognitive ideal of knowing the given clearly and surely would indeed be satisfied; but suppose what is given is ugly or painful, as much of human history must be to any clear-sighted spectator! The cognitive ideal is abstract, it is not the concrete object of desire, as any but a philosopher would be likely to see. Inconsistency and unclarity of belief are not the only evils or causes of evil, and their absence would not amount to all good.

(3) The doctrine does not mean that truth is merely coherence. Truth is coherence and clarity, but clarity in a radical sense not adequately suggested by such expressions as “clear ideas.” It is experience or awareness that must be clear, and no conceivable awareness can consist solely of ideas, if by that is meant awareness of universals. There must always be awareness of instances of universals, and these, with imperfect minds, are always unclearly given. Truth (other than purely general, philosophic) is clarity and distinctness, not just in ideas, but in awareness of events as illustrating ideas. Truth concerning events is “correspondence” of awareness with its contents, not just harmony of ideas with ideas. Nor does the harmony guarantee the correspondence. Hence God’s knowledge of truth must include an empirical element of direct intuition of events in their details; it must be knowledge by percepts, not by concepts alone. However, in God, correspondence with contents is guaranteed by his perceptual clarity and distinctness, or it just is this clarity and distinctness. The thing itself by its own evidence conforms the divine mind to its character. This leads to the criticism of the fourth misunderstanding.

(4) Ideal knowledge is not “impassive” or wholly “active” knowledge, which “makes” its objects and is in no sense made by them. To perceive is to be given form by an object, as the realists have well insisted. To say that our “being” is our presence to God is the same as to say that our being is our act of modifying the divine awareness. Ideal knowledge is as truly ideal passivity as it is ideal activity. Kant is one of the many thinkers who unwittingly exhibit the ruinous effects of the contrary assumption. Royce fell into this trap, when he termed God “will,” that is, sheer action. His grandiose attempt to justify evil was the result. Again, when Berkeley spoke of his “ideas” as “inert,” he unknowingly revealed that such ideas are not what is perceived. What is perceived is either universal, and then we must ask in what instance it is perceived, or it is particular, and the particular involves self-activity—for as Peirce and Whitehead keep pointing out, nothing external can wholly determine the particular or unique. Particularity and partial self-determination logically coincide.

(5) Our doctrine (it will already have been seen) does not mean that the object of knowledge is a mere idea, even a divine idea. An idea is a meaning, and a meaning does not mean itself. The real is what is given to God, content of his awareness, but what is given is not just the givenness itself, is not a mere state or adjective of the divine subject or substance, but a world of individuals other than, though not apart from or unpresented to, God. True, the being of these individuals is their presence to God, but it is their presence to him, and therefore their being, not just his presence to himself or just his being. Also, as remarked above, the individuals’ presence to God is partly self-determined. Thus the doctrine has nothing to do with epistemo-logical solipsism, according to which direct experience discloses no active individual save the one having the experience. Rather, experience is social and plural and objective, being the givenness of individuals to other individuals. Thus we are never (save in a limited and here not relevant sense) in the “ego-centric predicament,” for all experience has a measure of altruism, of participation in the life or activity of others. The ideal knower is simply the one able to participate fully and clearly in all beings present to him, these being the same as all that exist. For, as the absolutely unknown to any being is nothing for that being, so our recognition that there is more than we know is the same as our recognition that what we know we know imperfectly, and, by the same token, perfect knowledge defines the reality of its and our universe.

I wish now to touch upon five objections to this doctrine. One objection is that it might be more cautious or more intelligible to define reality as the limiting case of the contents of more and more coherent and clarified, yet still human, experience. I reply that we can not reasonably suppose that there are things only so far as human beings know them, even if we project this knowledge into the future and the possible. The world is older than man, and is more complex than his knowledge is capable of being. Also, to define reality as how things would appear to us if we were clear and certain is to define the is in terms of the might be, and this shift of modality is a paradox, if not a downright contradiction. Then, too, there seem obviously to be insuperable limits to human progress in clarity. Imagine knowing clearly what it feels like to be a butterfly, or a dinosaur, and while thus knowing, remaining a human being! Yet surely a butterfly does, and a dinosaur did, feel in its own definite way. Such clarity as we have concerning it seems to imply that inexorably.

A second objection is that reality might be defined as the system of causally connected items, including our experiences, but not constituted solely by experiences and not itself as a whole an experience. This, however, presupposes the idea of causal connection, and therefore confronts us with Hume’s problem of the basis of induction. Whitehead has, I think, shown that Hume can be answered, but only by treating causal coherence as a psychic and esthetic affair,1 so that we are brought back to experience as essential to reality. Further, the psychic account of causal order requires a supreme psyche to coordinate the acts of “decision” (Whitehead, but the same idea is in Peirce, Bergson, etc.) of lesser psyches, or experient subjects. These decisions are potentially anarchic to an unlimited extent, except for the universal influence of a supreme or divine decision. The point of the divine decision is not simply that it is right, while the others left to themselves would be wrong, but that it and it alone is cosmic and the same for all. All decision, even divine, is partly arbitrary (there are many wrong but also many right solutions of practical problems, as of the problem of traffic rules, which side of the road is to be driven upon, etc.). But whereas a mere multiplicity of arbitrary decisions is chaos, a multiplicity of arbitrary decisions can be comparatively ordered (absolute order is a mere limiting conception), provided there is one such decision which irresistibly and universally imposes limits upon the arbitrariness of the others. The resulting cosmic order will, in certain respects, be arbitrary too, but still an order, because (within limits) cosmically uniform. Now an ideally clear mind, essential to the reality of what it knows, will have the power to limit the disorder among its presented contents, even though, as has been said, these are partly self-mined. Such limitation of disorder will be an aspect of the clarity postulated; for chaos can not be clearly experienced. Absolute order cannot be experienced either, for it would be the absence of individual realities, of anything to experience.

It is not really a paradox that the contents should be subject to control, and yet self-active. Their being is their reception into the divine experience; but this being would not be theirs and there would be nothing to receive were they not partly self-active (inwardly self-determined, externally undetermined), particulars. They submit to partial control because they want to be, and they can not be except within an ordered and adequately inclusive experience. Their self-feeling is their feeling of contributing to each other as members of the living deity, by whose will they are all influenced so far as necessary to insure mutual relevance, and by whose appreciation their value is summed into a total good just that much greater because they have entered into it.

This brings us to a third objection: that the evil in the world contradicts the postulate of an ideal world-mind. But we have seen that the contents of the ideal knowing must be self-active. So far as self-active, what they make of themselves and of each other is their responsibility. It can not be God’s, unless it can be said that less evil would probably have resulted had he fixed the limits of their self-activity otherwise, and even then it must also be true that the hypothetical probability of less evil is not balanced by a probability of less good to the same or a greater extent. And it seems evident that the extent of possible good is determined partly by the degree of self-activity, that is, the depth of individuality, allotted to the contents, and that the extent of possible evil also varies directly with the same factor. Thus the demand that there be no risk of evil and at the same time abundant opportunity of good is probably nonsensical, and hence the fact of evil does not establish a counter-argument against the theistic explanation of reality. Nor does this explanation cancel human responsibilities. For we are not wholly determined by divine decision.

A fourth objection to the idealistic theory is that it is the function of knowledge to adjust itself to the real, not to bring it into being, such adjustment implying a prior reality or object. Now I have already granted much of this. As ideally passive, God does adjust himself to what is present to him. He does not “make” it in the sense of deciding its nature wholly on his own initiative. He allows it, within limits, to decide its own nature as divinely apprehended content. Also, since God has a past, and the past is determined once for all, therefore in now knowing a past event God simply preserves a content already constituted, a reality temporally prior to and independent of his present, though not his past, awareness. Admitting all this, we must still insist that experience on the whole supports the principle that to be is to be known. The enjoyment of friendship, the rôle of mutuality of experiences, the effect upon us of praise and blame, and of the belief that we shall be remembered after our death—these are some of the ways in which our sense of really existing draws tribute from our awareness of being known. Even a tiny child feels how nearly inseparable is his own being and its reflection in the awareness of other human persons. How much more literally and completely can reflection in God’s ideally sympathetic, that is, completely clear, appreciations constitute our reality! To be is to have value (including disvalue), for valueless being could not be the object of any interest, any attention, any meaning. But there is no conceivable interpersonal identity of value, such as can measure and constitute value as a public fact, unless it be the self-identity of an ideally appreciative personality.

A fifth objection may be put as a dilemma. Either we know the divine awareness, and then why are we not ourselves as omniscient as it is? or if we do not know it, then how can it explain our knowledge that there is more than we know? Naturally, one must reply by saying that in some sense we know the divine awareness and in some sense not. Or, we know the divine clearness unclearly. Thus the same idea, that of clearness, through its positive and negative aspects, or its gradations, defines both our ignorance and that of which we are (partly) ignorant.

I shall now sum up the advantages, or some of them, of this form of the theistic account of reality.

(a) The account gives unconstrained expression to the impossibility that an ideally clear and certain awareness could distinguish between what is and what is given to it, whereas other accounts imply that there must be such a distinction, and hence that an ideally clear experience would, paradoxically, undergo an invincible illusion from which we confused creatures are able to free ourselves.

(b) The account gives a positive definition of “reality” in terms of something known, namely, the internal characters of knowledge, whereas other views either fail to give a positive definition, or imply that the universe depends upon the human mind.

(c) It relates us to reality by a known type of relation, that of mutual sympathetic participation. The propositions: “We feel ourselves parts of an inclusive whole” and “We feel ourselves present to an ideal sympathy” differ in this, that we know what sympathy (including its ideal) is and how we can be related to it, but we do not know either what an inclusive wholeness not constituted by sympathy could be or how we could be related to it. Remember that the whole, or reality, must contain our feelings. Now a whole containing a number of feelings of diverse subjects is, in direct experience (the source of all meanings), illustrated only by certain phenomena of sympathy. How it is thus illustrated, Peirce, Fechner, Whitehead, and others have explained.2

(d) The account provides a solution of the problem of induction, which some competent logicians, including even Russell, have admitted is otherwise not very satisfactorily dealt with. An ideally clear mind, essential to the being of what it knows, will obviously have the power and the will to limit the disorder among its presented contents.

(e) Among the indications in experience that the sense of a reality transcending our knowledge is the feeling of our presence to a wholly transparent sympathy are intuitions and sentiments commonly called religious. But even the most secular among us, especially when we are at our best, have a feeling of contributing to some permanent and common good. Without this feeling, one act must seem to us as reasonable as any other, since the rational judgment of acts refers to the good on the whole and in the long run. Now how can human individuals, destined as they are for death, not only individually but, as it seems, collectively, racially, and lacking any but the most fitful and incomplete awareness of each other’s values, or even of their own past values—how can such as these serve any inclusive, permanent, common good, unless there be a God whose unitary, sympathetic, and deathless awareness, incapable of forgetting, derives value from our momentary and fragmented welfare?

Notes

1 This is admitted by William James (see “The Experience of Activity” in Essays in Radical Empiricism). I fail to see that radical empi-ricism solves the problem of truth without benefit of idealism.

2 The doctrine presented in this paper is the same as Whitehead’s, except so far as his affirmation, “The truth itself is nothing else than how the composite natures of the organic actualities of the world obtain adequate representation in the divine nature” (Process and Reality, Ch. 1, §5), is compromised, not to say contradicted, by his contention that even in God objectification is “abstract,” omits something, or “transmutes” the thing objectified. I suspect this mars his system, if insisted upon. Also, it seems quite unnecessary for God to take a hand twice over in the determination of reality, once in influencing its self-determining, and then in influencing how much of its concreteness is “immortalized” as the past objectified in him. What is not so immortalized is still something that happened, and so there are two pasts, that which is given in present (divine) actuality, and that which is not. But this latter, by Whiteheadian principles, is absolutely unknowable and meaningless, so far as I can see. Why not say that God’s influence upon the self-determining of the thing to be objectified takes care of any requirements needed to make it possible that it be concretely, fully objectified. If even God knows the concrete abstractly, wherein is his superiority. And does not “truth” remain a sort of super-God, unexplained in the system, thus construed. All this is, of course, but the beginning of a potentially long and compli-cated argument. I wish here to admit that in my controversy with Professors S.L. Ely and H.S. Fries concerning the “religious availability of Whitehead’s God” (Jour. of Liberal Religion, Vol. V, 1943, pp. 55 ff., 96 ff.; Ethics, Vol. LIII, 1943, pp. 219 ff.) I took insufficient account of Whitehead’s intention to apply the “abstract” view of objectification to God. Even so, if I could see sense in the resulting view of God, I could see some religious sense. But I question if the system permits or requires such limitation upon omniscience.

That Immanuel Kant omitted the idealistic argument for God from his allegedly exhaustive list of three arguments is curious, since the beginnings of this argument are obvious in his own system. He almost says, things as they really are coincide with things as given to an “intellectual” or divine intuition. If there be so such intuition, then appearances, with nothing that appears, must be all in all; which Kant himself says would be absurd. That he does not affirm, as positively conceivable, a divine or adequate intuition is due to his dogma that adequate intuition must be wholly active or impassive, and to his allegedly demonstrated conclusion that it must be non-temporal. But be adequate intuition conceivable or no, his system requires that it exist.