AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From Canadian Aesthetics Journal, Vol. 8, Fall 2003. This post reformats the text found here. “[This paper] attempts to explore the influence of Alfred North Whitehead’s process philosophy in the context of a fragment of music by J. S. Bach. The paper then proceeds, at a more abstract metaphysical level, to relate the aesthetic and artistic implications of the musical analysis to ultimate considerations, involving God.”

A Whiteheadian Aesthetic and a Musical Paradigm

Richard Elfyn Jones

In claiming completeness for his philosophy of organism Alfred North Whitehead wrote “it must be one of the motives of a complete cosmology to construct a system of ideas which brings the aesthetic, moral and religious interests into relation with those concepts of the world which have their origin in natural science.”1 Though he wrote very little about art, Whitehead’s writings have remarkable implications for art and aesthetics, not least in affirming that aesthetic value has a metaphysical primacy as the key to what is finally worthwhile in itself. But lest one define “aesthetic” too narrowly in this context, and take this to imply that Whitehead saw a uniquely overriding metaphysical role for art, we must clarify the wide-ranging meaning of “aesthetic” and “beauty” in Whitehead’s universe. The fact that each actual entity (also called actual occasion) embodies an aesthetic impulse towards order, meaning and value means that its concrescence (or coming to being) is essentially an aesthetic impulse towards the emergence of beauty. Whitehead’s very individual use of language has confused many a reader, so, before proceeding further, some explanation of his terminology and concepts is required.

Whitehead rejected a reality based upon substance in favour of reality as process. Accordingly, the smallest particles that exist at the sub-atomic level are not static substances but events of extremely brief duration that prehend, grasp, or feel, influences from their immediate past. These particles or entities (actual occasions) are drops of experience, complex and interdependent. “There is no going behind actual entities to find anything more real (. . .). The ontological principle can be summarised as: no actual entity, then no reason.”2 An actual occasion experiences concrescence, drawing the perishing past into the vibrant immediacy of a novel, present unity. In this process there is no such thing as spiritual matter versus physical matter, for all that exist (including God) are energy events. There are two aspects to prehension. Prehensions of other actual occasions are physical prehensions, and prehensions of eternal objects are mental or conceptual prehensions. Both aspects appropriate elements of the universe which in themselves are other than the subject, and in so doing synthesise the elements in the unity of a pattern expressive of their own subjectivity. Physical prehensions are always the data of the past, stubborn facts about the world as it was, and facts which process inexorably into the new actual occasion. But high grade organisms enjoy another kind of take-over from the past, namely, what man does when prehending concepts. This makes up the mental pole of prehension. In order to make the leap from inorganic to living societies Whitehead makes a sharp distinction between the physical and mental pole of each actual occasion. The physical pole is responsible for the automatic evolution of material reality. It is more or less devoid of novelty. The mental pole, on the other hand, has an element of subjectivity, is most striking in imaginative thought and is the source of all creative advance in the universe.

In prehending concepts we sense an objective scale of values in the form of eternal objects. Eternal objects are efficacious in all types of prehension, ranging from the sub-atomic to advanced societies, including human activities. Eternal objects are rather like Aristotle’ s universals in that they are to be found in the specific shared attributes of individual objects. The omniscient God includes all possibilities available for the concrescence of an actual occasion. These possibilities encompass the range of eternal objects that are relevant to the concrescence. According to Whitehead, it is through God’s appetition that a selection of the relevant eternal objects is allowed to ingress into its concrescence, so that, “the things which are temporal arise by their participation in the things which are eternal.”3 In his chapter on “Abstraction” in Science and the Modern World (1925), Whitehead, comprehends an eternal object in two ways, on the one hand, vis-à-vis its particular individuality in its own unique and peculiar form, and on the other, in its general relationships to other eternal objects “as apt for realisation in actual occasions.”4 The general relationship to other eternal objects implies that the eternal object varies from one occasion to another in respect to the differences of its mode of ingression, “for every actual occasion is defined as to its character by how these possibilities are actualised for the occasion.”5 Thus actualization is a selection among possibilities. More accurately, it is a selection issuing in a gradation of possibilities in respect to their realization in that occasion. Whitehead calls this principle of selective limitation the relational essence. Furthermore, for eternal objects to be relevant to process there is required a togetherness of eternal objects and, according to Whitehead, this togetherness must be a formal aspect of God.

To explain how this organic process works, we shall turn to one aspect of reality, to art, and to abstract music by J. S. Bach, a piece with no programmatic reference which might complicate our interpretation of its meaning.6 We chose this non-programmatic piece because abstract music represents process in a powerful way. Naturally, in order to illustrate Whitehead’s speculations, such is the universality of his philosophy that we could have chosen any aspect of reality. But our aim is specifically to explore a medium whose power possesses a depth dimension that, in the final analysis, lies beyond the world of concepts. Concepts are vital in explaining our world in all its aspects. But it has often been remarked that art, (and abstract art just as potently as religious, and thus programmatic, art) seems often to provide access to a deeper realm, even a divine reality. This may be because, in a number of ways, aesthetic experience is close to religious experience. There are parallels between them, the most notable being the power which both aesthetic and religious experiences possess for a direct and unmediated response to ultimate issues of reality. The discussion later on God’s persuasive role may help to relate the aesthetic and the religious aspect touched upon here. This will not be without an emotional aspect, bearing in mind that our exploration of the continuum between temporality and eternity, between matter and spirit, between man and what Otto called the “wholly other” will always respond to the numinous power concealed in real things, like, for example, pieces of music. But whether we react to Bach’s Mass in B minor quite like the person interviewed by Sir Alister Hardy is not for discussion here. In The Spiritual Nature of Man, the interviewee’s highly emotional description of an inspirational experience is profoundly personal and psychologically charged. She tells how,

[the] music thrilled me . . . until we got to the great Sanctus. I find this experience difficult to define. It was primarily a warning. I was frightened . . . I was not able to interpret this experience satisfactorily until I read—some months later—Rudolf Otto’s Das Heilige. Here I found it—the Numinous.7

We shall not indulge the emotional attitude found here, but rather confine ourselves to a rational, Whiteheadian approach. Speaking of music’s capacity to create aesthetic experience, Susanne Langer asserted that, “because the forms of human feelings are much more congruent with musical forms than with the forms of language, music can reveal the nature of feeling with a detail that language cannot approach.”8 We shall go further than this and assert that this and the other iconic designations of music are not necessarily restricted to the structure of feelings. As Paul Klee put it, art plays an unknowing game with ultimate things so that, in a manner similar to religious experience, it can penetrate depths of being in a direct and unmediated manner.

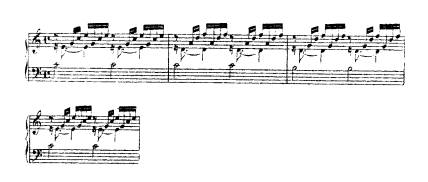

Whitehead’s advice was to start from some section of our experience in the belief that the knower, the percipient event, provides the clue to nature in general. Thus, in art the potentiality for becoming is no mere abstract concept, for since all actual occasions are dipolar, the physical and the conceptual must work hand in hand with an outcome that is real, and that produces a real experience. In art, creative advance into novelty is underpinned by the individual choices of the artist and his jealous involvement with inclusion and exclusion. In relation to a dipolar reality we can regard the opening note of Bach’s Prelude 1 in C major from the Well-Tempered Clavier as an individual essence, as middle C, 260 cycles per second. But as the root of the C major chord, this C has a determinate i.e. a relational, essence to other features of the tonality of C. Here C is the tonic and there is a fundamental axis of C (tonic) and G (dominant), both notes being eternal objects in mutual relation. A congruence exists between these predisposed tonal forces present in nature, and the creative manipulation of the creative artist (drawing in other notes and chords) so as to make a coherent pattern of 35 bars ending conclusively, as it began, on a C major chord. As the piece develops, the relational essence is extended, at least with regard to the choice of notes and the tonal progress. Unusually for Bach the rhythmic progress is very regular and repetitive, and even minimalist until three measures from the end, the result of deciding to base the piece throughout on a simple broken chord formula. We can follow the relational aspect in great detail, from the initial departure in measure 2 from C to a D seventh chord in third inversion whose relation to C is as a pseudo-dominant (it is not a major chord) to C’s own dominant, G major. The fundamental ploy of presenting chords 1, 5 and 2 (C major, G major and D minor) in relation to each other is characterised and enhanced by Bach’s decision in measure 2 to hold the C root so that it becomes the seventh of the D chord, thus exerting a compulsive tension demanding resolution down to B in measure 3.

The eternal object C (note), while remaining in the same place, has now changed its function. This is symbolic of what happens generally in music, where tonal progressions similar to what is found here facilitate subtle interrelationships between different notes whose functions change constantly, and which also bestow on an unchanging note (like the C here) a change in tonal, and therefore expressive, function. To describe this in Whiteheadian terms, we can say that while these chords are built on the determinate relationships of the overtone series, the specific instances of these harmonies are actual entities that have ingressed from the eternal object C major or, indeed, from the note C, which has a “patience” for the ingression. This is complicated by the fact that every eternal object is systematically related to every other eternal object, for a relationship between eternal objects is a fact which concerns every relatum, and cannot be isolated as involving only one of the relata. Accordingly there is a general fact of systematic mutual relatedness inherent in the character of possibility. “The realm of eternal objects is properly described as a ‘realm’, because each eternal object has its status in the general systematic complex of mutual relatedness.”9 In referring to the relationship of eternal objects to actual occasions, Whitehead wrote:

The general principle which expresses A’s ingression in the particular actual occasion a is the indeterminateness which stands in the essence of A as to its ingression into a, and is the determinateness which stands in the essence of a as to the ingression of A into a. Thus the synthetic prehension, which is a, is the solution of the indeterminateness of A into the determinateness of a. Accordingly the relationship between A and a is external as regards A and is internal as regards a.10

The eternal objects are ingressed by selection, and prehending them involves the grading of possibilities. At all microcosmic levels this is highly complex, and with regard to our musical example there will be a multitude of graded possibilities as each harmony progresses to the next. On a wider canvas, this grading of possibilities is quite striking in the overall form of Prelude 1.

Since its evolution as a piece has been documented, it is possible to study some revisions and expansions that suggest an ongoing grading of possibilities by Bach. From an initial version of 24 measures the piece was expanded to 27 measures before assuming its final definitive form of 35 measures. An examination of the various different versions shows the final masterpiece emerging as a distillation from the possibilities suggested by the simple basic material. The insight this gives into Bach’s uniquely powerful control over tonal possibilities, not to mention the lyrical inspiration of it all, is a revelation that needs no further comment here.11 Implicit are the hidden possibilities, other valid choices available for Bach, and not just those seen in the two less accomplished versions of this Prelude. Bach did not exhaust all the possibilities; he was concerned with one only. We may assume that excellent possibilities remain unrealised, despite the feeling we might have that this Prelude is unique and exists in the most perfect conceivable form. In noting the different versions we see that, between any form and any other, there is inevitably a continuum of possible intermediate forms. There are alternative suggestions, “untrue propositions”12 which lie undisclosed. To comment further on these undisclosed possibilities seems fruitless, as Whitehead’s pupil Charles Hartshorne implied when he said, “counting to infinity is an incomplete process.” Like Whitehead himself, we must accept that reality is found in actual occasions, and only in them.

Since creativity brings together the actual creations of man and the divine principles from which those creations derive, there is both a concrete togetherness and novelty to it. According to Whitehead, both things must happen simultaneously, for to produce togetherness is to produce novelty and vice versa. “The ultimate metaphysical principle is the advance from disjunction to conjunction, creating a novel entity other than the entities given in disjunction,”13 and this is fundamental to Whitehead’s doctrine of process. The eternal objects, of course, are not subject to change, in that it is of their essence to be eternal. But they are involved in change insofar as the very process of becoming, which is any given actual occasion, depends on the control of the selected eternal object or objects. There cannot be anything novel (that is, different from what is already actual) unless there is a potential for it. In Science and the Modern World, God is described as the principle of concretion. In the process whereby events come into concreteness, with an initial phase being dependent on prehending the immediate past environment, (so as to take over from predecessors) Whitehead posits various parameters: namely that an occasion is both in essential relation to an unfathomable possibility and is an occasion that has limitation imposed on possibility. But how is this awesome ordering and balance of value achieved? And what matters of fact are necessary for it to succeed? While bestowing the infinite possibilities of the eternal objects according to various principles of value, God reins them all into a coherent harmony so that all actuality is harmoniously graded. God therefore functions as the principle of limitation, imposing order on the infinite possibilities of the eternal objects. In Science and the Modern World Whitehead asserted that God is an explanation: “God is not concrete, but he is the ground for concrete actuality.”14 Shortly afterwards, in Process and Reality (1927-28) there is a remarkable and unexplained shift to the assertion, consistently made thereafter, of God as an actual entity: “God is an actual entity and so is the most trivial puff of existence in far-off empty space.”15 Whitehead clearly regarded his original idea of the inscrutable and lonely God as a fundamental inconsistency, and incompatible with one of the aims in Process and Reality, namely, to rid philosophical discourse of what hitherto had been “enmeshed in the fallacy of ‘misplaced concreteness.’ In the three notions—actual entity, prehension, nexus [a collection of entities]—an endeavour has been made to base philosophical thought upon the most concrete elements in our experience.”16 Self-sufficiency is incommunicable, as is unlimited excellence, and if God is not an actual entity then nothing is possible. Whitehead’s ontological principle asserted that, apart from things that are actual there is “nothing either in fact or in efficacy.”17 If God is himself conceived as an actual entity who works as an agent for maximising and harmonising values, then, in this form he is enduring, and, as an enduring subject, he relates temporally and in a temporal world; for God’s mode of relationship with other subjects is through his actions having an effect upon the world and its agents and modifying the world in accordance with his intentions. This logically entails a self-imposed limitation upon his absoluteness; for if he acts in the temporal world, then he makes himself available to receive, in this very same field, the acts of non-divine agents. This also implies both a reaching out by God and his dependence on others. If the world needs God, then God needs the world. If God is no exception to metaphysical principles, and if his authority is seen to be restricted and curtailed by this self-imposed consequential nature then, one rational argument for it is the assertion that a creator God must have a social bond which he has created, notably with higher organisms such as ourselves. In other words, why not follow the dynamics of creative involvement in which creator and created affect each other selectively? As one writer put it, to be fully God he needs the universe. If, after creating the universe, the divine reality was exempt from the multifarious diversity of his creation, then what is the point of the creation and what is the universe’s purpose? Since God is actual he must include in himself a synthesis of the total universe. Therefore, God is immanent in the world and is an ordering entity whose purpose is the attainment of value in the temporal world. The ordering entity is a necessary element in the metaphysical situation presented by the actual world.

Since all reality, including God, is in process, the ongoing nature of God’s intimately linked with a world whose processive realities are joined to one another. As we have noted, Whitehead emphasises the togetherness of eternal objects on which creative order depends. This precise monism, in which all reality is unified, was at the core of Hartshorne’s panentheism (literally pan-en-theism), which validated God’s transcendence by maintaining that everything exists in God. God contains all. If such were not the case, argued Hartshorne, and if this supreme being was not all-inclusive, then there would be a total reality superior to the supreme. God would then have the status of a mere constituent. On the other hand Whitehead always asserted the freedom of non-divine subjects, whether that be me gardening or Bach, with an awesome sense of awareness, penning the Prelude as one of more than a thousand works indicative of a profound understanding of what can be produced from the overtone series (if that is not too superficial a description of this composer’s formidable skills).

In Process and Reality Whitehead explains how God as primordial is the ultimate cause for each actual occasion being endowed with a “subjective aim,”18 that is, the purposive element affirmed as present in every occasion. God gives to every entity its initial conceptual aim, which the entity afterwards proceeds to modify for itself. Whitehead deduces the source of novelty in the universe as flowing from the divine fountainhead, and the procedure whereby God actualises himself in the world is described explicitly in Whitehead’s doctrine of God’s participation in an occasion’s initial aim. The initial stage of the actual occasion’s aim is rooted in the nature of God, and its completion depends on the self causation of the subject. This is one of Whitehead’s most striking and creative metaphysical doctrines.

God’s persuasive (rather than coercive) wisdom imbues the initial aim of every concrescence. This occurs at the start of each occasion’s reaction to the influence from the past; the initial aim evaluates the initial gradations of relevance of eternal objects and God’s all-embracing conceptual valuation is harnessed to the particular possibilities of the actual, “by its relevance to the various possibilities of initial subjective form available for the initial feeling.”19 Later, Whitehead wrote: “there is constituted the concrescent subject in its primary phase with its dipolar constitution, physical and mental, indissoluble.”20 As we have said, from this point onwards the concrescence determines its own definiteness. Such is the freedom allowed to the concrescing entity that, while the initial aim is infused by God directly, the actual occasion’s subjective aim refers to the active appropriation by the concrescing entity of what it decides freely to take as its own personal goal guiding it towards its characteristic action. God then becomes the source of the systematic introduction of novelty into the world process and for the co-ordination of all the varied activities of a harmoniously evolving world order. Whitehead asserts that, apart from the intervention of God, there could be nothing new in the world and no order in the world. The course of creation would be a dead level of ineffectiveness, with all balance and intensity progressively excluded by the cross-currents of incompatibility. If this is correct, truth in art is possible only if it conforms to the patterns at the microcosmic level. Art is not a realm apart from the fundamental structures of God’s universe—it is indissolubly linked to reality, and hence to the world. So a work of art is loaded with what can be called ulteriority. As Whitehead tells us, “The relata of Reality must lie below the stale presuppositions of verbal thought. The Truth of Supreme Beauty lies beyond the dictionary meaning of Words.”21

Notes

1 A. N. Whitehead, Process and Reality [Corrected Edition] (New York: Free Press,1978), xii.

2 Ibid., 18 and19.

3 Ibid., 40.

4 A. N. Whitehead, Science and the Modern World (Glasgow: Collins,1975),191.

5 Ibid., 191-2.

6 Many years after Bach’s time this piece, the first Prelude from the Well-Tempered Clavier, assumed a programmatic religious meaning when Gounod borrowed it to make an instrumental accompaniment to his Ave Maria.

7 Alister Hardy, The Spiritual Nature of Man (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1979), 85.

8 Susanne Langer, Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Symbolism of Reason, Rite and Art (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1957), 191.

9 Science and the Modern World, 193.

10 Ibid., 192-3.

11 The idea of Michelangelo "releasing" a figure from the rock is a familiar one to a number of artists, working in all forms, who might regard themselves as artistic vessels or conduits.

12 See Science and the Modern World, 190.

13 Process and Reality, 21.

14 Science and the Modern World , 213.

15 Process and Reality ,18.

16 Ibid.,18

17 A. N. Whitehead, Religion in the Making (New York: Macmillan,1926), 99.

18 Process and Reality, 25.

19 Process and Reality, 244.

20 Ibid., 244.

21 A. N. Whitehead, Adventures of Ideas (New York: Macmillan, 1933), 343.