AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

From Time, April 20, 1970, p. 76. The first sentence of this article is the source of a blurb that appears on the back of the Harper & Row paperback edition of Lonergan’s Insight: A Study of Human Understanding. The occasion of the Time story is the International Lonergan Congress that was held at St. Leo University (then St. Leo College, 35 miles north of Tampa, Florida) in April 1970 and the contemporary growing interest in Lonergan's work. Two volumes of papers came out of that meeting: Foundations of Theology and Language, Truth, and Meaning, both edited by Philip McShane and published by the University of Notre Dame Press in 1972.

Anthony Flood

February 26, 2013

The Answer Is the Question

We should have questions on everything, about everything.

— Bernard J.F. Lonergan

CANADIAN Jesuit Bernard J. F. Lonergan is considered by many intellectuals to be the finest philosophic thinker of the 20th century. This month, 77 of the best minds in Europe and the Americas—critics and admirers, Protestants, Roman Catholics and agnostics—gathered to examine Lonergan’s profoundly challenging work at rural St. Leo College near Tampa, Fla.

Many of the names were celebrated: English Philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe, smoking her trademark cigar, Radical Poet Kenneth Rexroth, Expatriate Catholic Theologian Charles Davis, Biblical Scholar John L. McKenzie, Protestant Theologian Langdon Gilkey, U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy. As McCarthy said of the assemblage, which included mathematicians and scientists as well as theologians and philosophers: “You would have to spend ten years going around the world to find all these people.”

All-Embracing Theory. Such a constellation of scholars attested to a renewed and heightened interest in Lonergan, who is now writing extensively again after recuperating from a 1965 operation for lung cancer. That they came from so many disciplines demonstrated that Lonergan’s influence has gone far beyond his original field of theology. In fact, says Fordham Jesuit Bernard Tyrell, Lonergan has become a true “philosopher of culture”: in his grasp of the process of understanding that underlies every science, he is the 20th century counterpart of a Renaissance man.

The effort, nonetheless, began with Lonergan’s theology. As a teacher of seminarians for 25 years—including twelve years at Rome’s Pontifical Gregorian University—Lonergan recognized that a persuasive theology could only be based on a thoroughgoing study of how theologians think. This led him to immerse himself deeply in epistemology, the study of man’s knowing process.

Ultimately, his studies produced what is thus far his masterwork, Insight, published in 1957. In this book and in later papers, he develops an all-embracing theory of knowledge that includes every area of human understanding, not least of them the awareness of God. Though Lonergan grafts from the scholastic tradition of St. Thomas Aquinas, he has long since gone beyond Thomism, much as Aquinas transcended Aristotle. His particular distinction is that he shares modern philosophy’s concern for each man’s uniqueness, and sees man’s own self-understanding as the key to understanding the universe around him. He thus echoes the Athenian exhortation γνῶθι σεαυτόν—know thyself.

Lonergan insists that his method is rigorously empirical. His Insight devotes some 750 pages to a closely reasoned demonstration that the same process of understanding that applies to “insights” in mathematics and the physical sciences also applies to theology. To a neophyte, he will patiently explain that it all boils down to three questions: “What am I doing when I am knowing? Why is that knowing? What do I know when I do that?”

Lonergan’s method is his own, but he clearly owes a debt to the phenomenologists, particularly to German Philosopher Edmund Husserl. For the phenomenologist, the material evidence of a perceived object is screened by the dynamic (and very personal) phenomenon of the act of knowing. Husserl developed this into the idea of “horizon”—the vastness or narrowness of the world a man perceives. For Husserl, a man’s horizon is limited by his perspective: his environment, his loves and fears, his interests and prejudices.

Adapting this idea of horizon, Lonergan makes it part of his theory of knowledge. A man can alter his horizon by recognizing it as a limitation on his ability to know—indeed, as a limitation on the very questions that he must ask in order to know. He can open himself to information from outside his horizon, use that information to formulate new questions, and continue to grow. By thus transcending his limitations, a man undergoes “conversion,” which may be moral, intellectual, social or religious. In Lonergan’s approach to theology, which he will spell out in detail in a forthcoming major work to be called Method in Theology, the ultimate horizon “is an openness to an experience of God.

Rational Authority. The issue of Lonergan’s approach to God became a principal focus of criticism at the Florida meeting, where Lonergan specialists were more than matched by “critical respondents.” The participants heatedly debated whether any such system as Lonergan’s could any longer hope to embrace all knowledge, and especially whether it could provide a proof of the existence of God. “He comes up with an argument for God out of the blue sky,” objected Georgetown University’s Louis Dupre. “He develops a concept of being into a concept of God.”

Chicago Divinity School’s Langdon Gilkey conceded that Lonergan’s theological method has an “uneasy relationship” to his scientific method, but he applauded Lonergan’s overall thought. “He has imbibed the empirical, the hypothetical the tentative,” said Gilkey. “Yet within it he has a structure that breaks the back of relativism.” Gilkey agrees with Boston College Philosopher David Rasmussen that, for Catholicism, Lonergan may be the liberating force that Friedrich Schleiermacher was for 19th century Protestantism. But for liberal Protestants, Gilkey notes, Lonergan could provide something of a brake to excessive subjectivism. “He has a way of freeing one from authority, yet setting up a rational authority.”

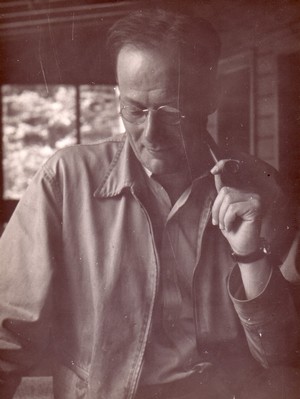

Lonergan, who attended the congress sessions in a seldom-varying uniform of plaid sports shirt, slacks and windbreaker, listened attentively to both praise and criticism. At 65, with only one lung, he was remarkably energetic throughout the grueling week-long conference, dutifully setting aside spare moments to read many of the 700,000 words that participants had written about him. “I don’t care whether they agree with me or disagree with me,” he said. “What matters is that they are here, talking with each other.” Seminarian Joseph Collins, a well-to-do young activist who personally paid travel expenses for the participants, marveled at the quality of the debate: “I really didn’t think they could interact.”

Jesuit Joseph Flanagan, a longtime Lonergan scholar, was much less surprised. For Flanagan, Lonergan’s method “not only includes but demands interdisciplinary dialectic. We must learn from one another.” To do otherwise, says Flanagan, simply contributes to “the pool of misunderstanding” that in Lonergan’s thought lies at the source of so many of mankind’s woes.

Major Catalyst. Some critics charge that Lonergan’s thought is inhibited by his need to justify Catholic dogma. Charles Davis, British theologian who broke completely with the Catholic Church, admitted at the conference that “I should never have been able to leave the church had it not been for reading Lonergan. I did not have to destroy my past. I could grow out of it.” Nonetheless, Davis said, Lonergan has always been an apologist for the church, and his search for a secure foundation for dogma still “governs the whole enterprise.”

Others who have been influenced by Lonergan also see him, in a somewhat different focus, as a major catalyst in their thinking. Notre Dame’s David Burrell and John Dunne, Chicago Divinity School’s David Tracy, and Humanities Professor Michael Novak of the State University of New York, all studied under Lonergan at the Gregorian, and each attributes his own free-roaming theological method to Lonergan’s influence. “Insight gave me the freedom to go on through trusting my own understanding,” says Burrell. “It is not the system,” says Dunne, “but what Lonergan does. He moves from one horizon to another while talking about insight. It is a voyage of discovery.” For Tracy, whose book The Achievement of Bernard Lonergan will be published next month, Lonergan means: “You can’t cheat. You know what is demanded of real thinking.” Michael Novak finds Lonergan’s importance in the fact that all education is the developing of insights. But “this is not a school of philosophy,” warns Novak. “Nobody can have your insights for you. If you make a school out of Lonergan, you’ve missed the point.”

Perilous Adventure. Lonergan himself insists that “there is no such thing as a Lonerganian”; by its very nature, he says, his method “destroys totalitarian ambitions.” Insight is “a way of asking people to discover in themselves what they are.” Yet the very openness of Lonergan’s method, notes Utrecht University Theologian Henri Nouwen, makes his approach to self-realization a perilous personal adventure. The answer to intellectual blindness—or scotosis, as Lonergan calls it by its Greek name—is that each human being must lay himself open to the sheer terror of self-discovery.

Lonergan repeatedly emphasizes that self-discovery demands considerable individual responsibility. In a recent essay on “The Absence of God in Modern Culture,” he points out that honest concern for the future of the world must begin with self-transcendence. “If it is not just high-sounding hypocrisy,” Lonergan concludes, “concern for the future supposes rare moral attainment. It calls for what Christians name heroic charity.”

Some of his critics object that such earnest expressions of Christian love are all too rare in Lonergan’s work—that he is too rational, that the dimensions of feeling are absent. Lonergan replies simply that love is already at the heart of the matter. “Being-in-love is a fact. It’s a first principle. Being-in-love doesn’t need any justification, just as you don’t explain God, God is the ultimate explanation. Love is something that proves itself.”

Lonergan does not pretend to comprehend everything, but only to offer a dynamic viewpoint in which everything may be seen to be part of an interrelated whole. It is at heart a simple method but, like Jesus’ great commandment of love, it is not easy. Critics who say that it offers too many answers do not grasp the essential Lonergan. What he may offer, for many people, is too many challenges. Despite the promise of an ultimate horizon, there is in that offer no solid assurance of an answer that can be grasped in mortal life. There is only the tantalizing guarantee of a continuing question.