AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

A few passages from Insight: A Study of Human Understanding, 1957, are followed by an abstract of an undelivered talk, “Philosophic Difference and Person-al Development,” which abstract was published in The New Scholasticism, 32 (1958) p. 97.

On the Nature of Philosophy

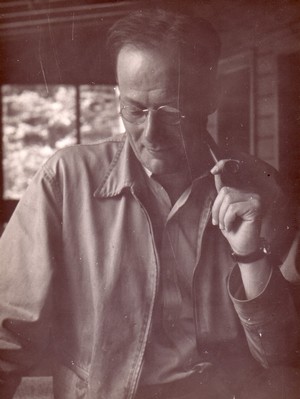

Bernard J. F. Lonergan, S.J.

“Philosophers and philosophies engage our atten-tion inasmuch as they are instances and products of inquiring intelligence and reflecting reasonableness. It is from this viewpoint that there emerges a unity not only of origin but also of goal in their activities; and this twofold unity is the ground for finding in any given philosophy a significance that can extend beyond the philosopher’s horizon and, even in a manner he did not expect, pertain to the permanent development of the human mind.” 387

“Philosophic evidence is within the philosopher himself. It is his own inability to avoid experience, to renounce intelligence in inquiry, to desert reason-ableness in reflection. It is his own detached, disin-terested desire to know. It is his own advertence to the polymorphism of his own consciousness. . . . It is his own grasp of the dialectical unfolding of his own desire to know in its conflict with other desires that pro-vides the key to his own philosophic development and reveals his own potentialities to adopt the stand of any of the traditional or of the new philosophic schools. Philosophy is the flowering of the individual’s rational self-consciousness in its coming to know and take possession of itself.” 429

“Metaphysics has been conceived as the integral heuristic structure of proportionate being. It envis-ages an indefinitely remote future date when the whole domain of proportionate being will be under-stood. It asks what can be known here and now of that future explanation. It answers that, though the full explanation may never be reached, at least the structure of that explanatory knowledge can be known at once.” 431

Philosophic Difference and Personal Development

In Europe at the present time, there is a wide-spread disaffection for St. Thomas and not a little favor for the apparently timely doctrines of personal-ists, phenomenologists, and existentialists. In Amer-ica, while Thomism holds a secure position among Catholic philosophers, it does happen that those who, after a course in Scholastic philosophy, have gone on to other specialized fields, at times exhibit a marked hostility to the philosophy in which they had been educated.

It would seem difficult to disassociate this phe-nomenon with problems of personal, intellectual development. A new higher viewpoint in the natural sciences ordinarily involves no revision of the sub-ject’s image and concept of himself, and so scientific advance easily wins universal and permanent accep-tance. But a higher viewpoint in philosophy not only logically entails such a revision but also cannot be grasped with a “real apprehension” unless the re-vision actually becomes effective in the subject’s mental attitudes. So the philosophic schools are many, and each suffers its periods of decline and revival.

It was to foster such a “real apprehension” of one’s own intelligence and reasonableness and to bring out its intimate connection with the funda-mental differences of the philosophies that the pre-sent writer labored in his recent work, Insight.

Posted April 12, 2008