AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From The New York Times Book Review, May 26, 1968, 4, 5, 35. The original title was simply, “A Lady Seeking Answers.”

Posted November 23, 2008

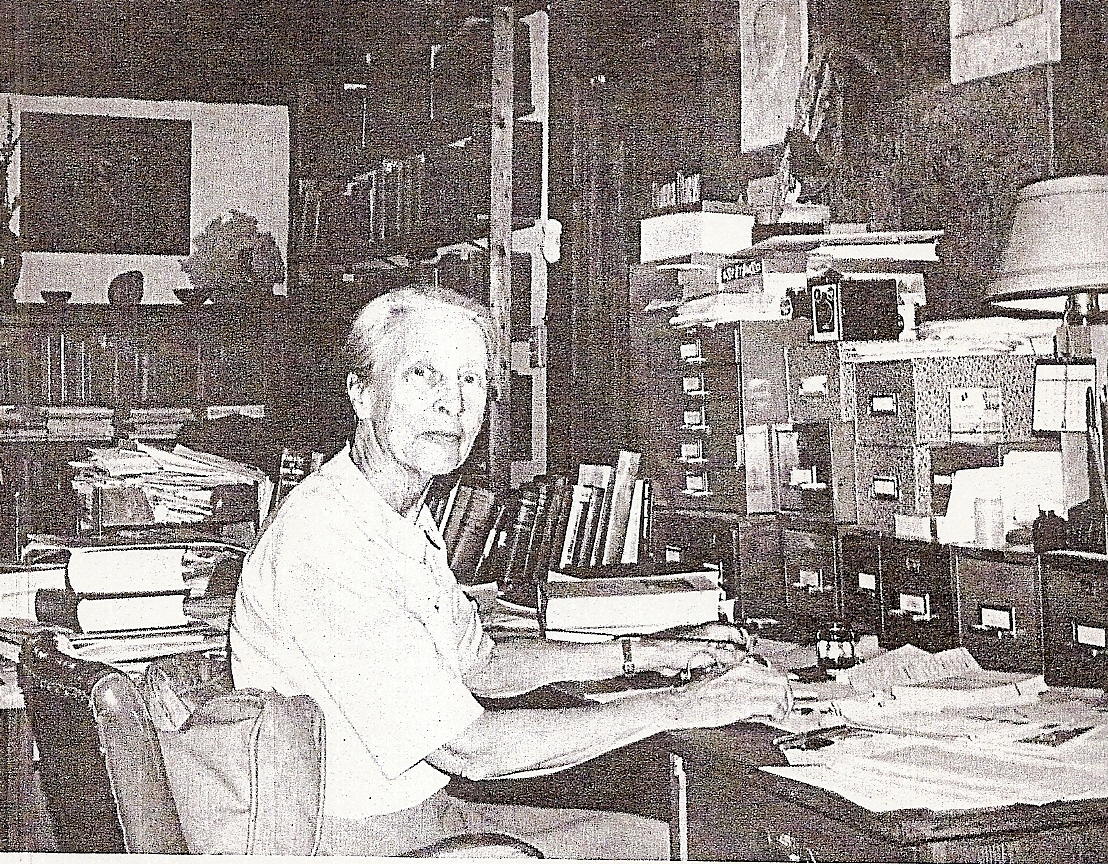

Photo by James Lord. The poor quality is the result of a scan of a print-out of microfilm. If there is a reader who has a physical copy of the magazine and therefore can provide a better digital reproduction, I would appreciate hearing from him or her. -- Anthony Flood

Susanne Langer: A Lady Seeking Answers

James Lord

Susanne K. Langer lives in an old New England farmhouse. Barn red, facing the afternoon sun, it stands close to the roadside but well above it, unassuming and inconspicuous. The interior, like all places where a person has lived alone for a long time, is intimately expressive of its inhabitant. Writing occupies one axis of the large L-shaped living room, music the other. Where the two join stand several chairs, a table and a couch; the walls are lined with bookshelves from the floor almost to the low ceiling. At the end of the music area, beyond the grand piano, a glass-doored cabinet holds a cello and two violins. The writing area is all but filled by two desks and a card table pushed together to afford maximum space for a row of large card files, piles of manuscript and the books and journals which are the tools of current research.

Throughout the room are paintings, drawings, sculptures and other artifacts which reflect Mrs. Langer’s tastes not only in art but in nature as well. And there are the many books in English, French and German, languages that she uses with equal fluency, books mostly of logic, philosophy and esthetics, fields which occupied many years of her teaching career, but also works touching on the various forms of art as well as the areas of biology, physiology and psychology, which have assumed increasing importance in her more recent works. On shelves, tables and window ledges stand jars and aquariums that contain fish, spring peepers, tadpoles and turtles. Nothing in the room is contrived for the regard or impression of the visitor. It serves purely to provide comfort and utility to its inhabitant—a room uninfluenced by the fashions.

Susanne Langer is slight but not frail, and as in her habitat so in her appearance little seems to have been calculated for the eye of the visitor. Her dress is informal and she uses no cosmetics. Her fine, gray hair is trimmed close. For one who frequently spends 10 hours a day writing and reading and who is now past 70 she holds herself alert and erect with notable vitality. As she speaks she calmly and continually folds and unfolds her fingers, which have the tensile, slender finesse of seasoned self-discipline. Her tone itself is disciplined even when humorous.

“What I am trying to do,” she said, seated between the window and the piano, “is to break through current forms of thought in biology to form a framework for biological theory which will naturally result in a theory of the human mind.”

To challenge the existing boundaries of scientific thought! Not by chance, not by the single intuitive tour de force that is occasionally the happy experience of the laboratory scientist, but by the deliberate and rigorous, exercise of intellect. Not for immediate utility, not for pure intellectual enjoyment alone, but for the practice and profession of understanding. It is a purpose clothed in the beauty of natural self-evidence. Finding the coherent structure which threads through an almost infinite complexity of interdisciplinary data and thought is a challenge to the passive fatalism of those who accept the world as it appears and feel that life unexamined and uncriticized is well worth living.

Such sovereign participation in the future of human awareness is not what one expects to find along a Connecticut roadside. But Mrs. Langer herself is among those surprises of experience that dispose one to contemplate contingency with pleasure. She is the world-famous author of Philosophy in a New Key, Feeling and Form and, most recently, Mind: An Essay on Human Feeling, of which the first of three volumes was published last year and which she regards as her magnum opus. She has vitally influenced not only other philosophers but artists and scientists as well in their concepts of function, and her theories are discussed with vivid concern in both studios and studies. Her works as well as her aspirations have remained serious and life-enhancing, and reflect a lively awareness of the “state of the art” of the various disciplines from which she draws. This awareness and seriousness of purpose naturally dominate one’s impression of her as a person.

Born in New York City of well-to-do German-born parents, Mrs. Langer as a child spoke German exclusively at home. Her early education was at a French school in New York, and it was not until she entered Radcliffe that English became the completely integrated means by which she communicated with the world. It is interesting to conjecture that this multiplicity of communicative means early in her life may in some measure account for the universality of Mrs. Langer’s present response to living phenomena.

At Radcliffe she majored in philosophy and after her marriage to William L. Langer (then also a graduate student at Harvard, where he went on to become a distinguished historian) she remained there to complete her doctoral work, chiefly in logic, and to teach philosophy. In these early years of her professional career she also wrote ‘The Practice of Philosophy and An Introduction to Symbolic Logic. The Professors Langer were divorced in the early 1940’s; their two sons became neither historians nor philosophers but rather a banker and a computer technologist. For many years Mrs. Langer has served on the faculty of Connecticut College, where she is now professor emeritus, though for most of the last decade her efforts have been directed entirely to her writing. This work has been supported by the Kaufmann Charitable Trust, an organization distinguished by its willingness to wait 10 years for the first finished product of its generosity.

When conversation about her background gives way to a discussion of her philosophical concerns, Mrs. Langer takes on the patient, purposeful authority of a trained teacher and practiced writer. Yet a certain diffidence prevents her intellectual authority from intimidating the visitor. She knows that the fields of her activity are abstruse and tries to make it easy for others to ask questions. Facing her blue-eyed, contemplative gaze, the visitor asks: “Would you say that your purpose is to think rationally beyond the previous limits of human knowledge?”

“Perhaps that would be a rather presumptuous or grandiose statement of objectives. Let’s say instead that I am trying to tie together a number of disciplines into a structure that these disciplines—the arts, biology, neurology, psychology, language, anthropology and others—won’t themselves singly support. I am trying to develop basic concepts which underlie all these sciences or fields of study and which can rule all such thought.”

“But how does one go about such work?”

“You must have the means to develop coherent concepts that are sufficient to build up a conceptual structure which will be adequate to the experiential facts you want to describe, and which will not only allow you to characterize but also to manipulate possible relationships in such a way as to discover relationships you had not previously seen.”

“Some very particular talent must be required to do that, mustn’t it? Some innate capacity or aptitude?”

“A great freedom with abstractions, for one thing. I have always had that. I find logic and mathematics easy—but not visual mathematics. For instance, I always have to translate in my mind all geometry or visual constructions into algebra. What really was decisive for me, though, was 10 years’ study of symbolic logic. That taught me how to hold many ideas simultaneously in my mind. I can entertain a proposition without having to say that I do or don’t believe it. One plays with many possible forms at once. It’s the gestalt principle, as for example, when one looks at a wallpaper that has a particular geometric pattern and sees alternative configurations, triangles, that is, jumping suddenly to form larger triangles, stars or parallelograms. The ideas with which I work are analogous to such an ambiguous pattern. To be able to deal in this manner with abstract ideas is essential when one is trying to break through the historical limitations of theory.”

“It must be necessary to have an exceptionally retentive memory.”

“It would certainly be helpful. My verbal memory is like fly paper. Everything sticks to it. That is both good and bad, because one’s mind becomes filled with irrelevant as well as useful things. For instance, I still remember any number of rhymes from advertisements that I saw in my childhood, and these pop into my head at the most unexpected and ridiculous moments. At the same time, however, I remember reams of the fine poetry I’ve read over the years, and that is a delight to recall. Though my verbal memory may be exceptional, my visual memory is unfortunately far from good. I have trouble recognizing faces I have seen even more than once. A poor visual memory is a particular handicap in handling source material in research. That’s why I have to keep the elaborately cross-indexed system of file cards which you see in those boxes on my desk. Those 12 boxes and six more like them in storage upstairs, each one holding about a thousand cards, contain notes on every professional book and journal that I’ve read since my junior year in college. It’s the only way that I can put my hands immediately on my source material. Had I been blessed with a better visual memory, this filing would not have to be so involved and time-consuming.”

“Although you have written a great deal about the arts, your current work is not specifically concerned with the arts, is it?”

“No. It is not simply an extension of what I said in Feeling and Form. Many of the people who have written about the new book, including some eminent critics, have made that mistaken assumption. What I am trying to do here is to arrive at a conceptual framework for literal thought about organic nature without losing sight of the actual phenomena which those concepts are supposed to describe. The image of life is in art. An image is not a model, and it can’t be used for scientific investigation. An image shows how a thing looks, while a model shows how it works.”

Mrs. Langer is in eloquent control of the afternoon. Choosing words with evident concern, she seems to draw upon a matrix of disciplined perception sufficient to elucidate the most abstruse phenomena. In answer to the question whether or not it is possible to say exactly what one thinks, she replies, “Yes, I believe that we can, because language, while it clearly has its limitations, is the only instrument through which we can formulate thought. Remember, though, that the term ‘language’ encompasses not only the written and spoken forms that most people use in everyday life; but also the less common symbolic forms of the mathematician, the physical scientist and others. These forms have been developed just because of the limitations of ‘ordinary’ language and permit their users far greater precision in expressing thoughts. The precise relationship between language and thought presents a number of significant psychological problems which are still largely unexplored. One comes, upon surprising discoveries.”

“Could you mention one?”

“Yes. I mean, for example, such a discovery as Freud made when he observed that in dreams speech has the same function as a visual image.”

A future part of Mrs. Langer’s work will be devoted to the enigmatic nature of language and its radical difference from all forms of nonhuman communication. While animal communication is always emotional or directive, the essence of language is expression of ideas. In this connection she pointed out that even if one is engaged in expressing concepts of a very definite character one cannot account for the origin of the specific words which present themselves to the mind as uniquely appropriate to the purpose at hand.

Sometimes a word may occur but then almost at once vanish, bearing with it the essence of a particular thought, and no amount of longing or patience can summon it back. Like many writers, accustomed to these quirks of the mind, Mrs. Langer has trained herself to dominate, but at the same time to. Stimulate, that welling of words which is inseparable from the awareness and expression of thought. This is essential to the juggling of ideas which she describes as an integral component of philosophical activity.

Once generated, however, the verbal stimulus is not always easy to arrest, and it often happens that fruitful perceptions may take their authors by surprise at irrelevant or vulnerable moments. Mrs. Langer keeps a stack of filing cards besides her bed and by guiding the movement of her hand with a little finger held at the edge of the stack has taught herself to write four or five lines of legible script per card in the dark. Such spontaneous experience of those mental processes common to all imaginative writing may reasonably lead one to wonder whether Mrs. Langer’s work does not within its own conceptual framework also have an artistic essence.

“Not really an artistic essence,” she replied, “but it is full of literary problems which are, of course, artistic. Philosophy always aims to present actuality, while for an artist actuality is but raw material. Art creates a semblance that exists in its own right. My work is about actuality, and insofar as it may create a semblance the essence of it is that such a semblance should fit actuality. Even the stylistic devices are to make the concept easier to grasp.”

Here in this quiet, bright and rather untidy room, day after day and for years a lone woman has lived at grips with concepts of basic actuality. One wonders what sort of a life it may be. Solitary, she acknowledges, indeed solitary. The community comes and goes about her; she takes no active part in it. But does nothing serve to leaven this existence of intense intellectual activity?

Recreation? Mrs. Langer smiled obliquely. There is the housework, of course, which she does principally when tired after a long day of reading and writing. And there is music. Music, in fact, would appear to be her principal recreation. If it may properly be called that, for Mrs. Langer observed that effective practice of the cello, which is her instrument, requires a degree of mental vitality and concentration that she can ill afford to spare from her philosophical work. Accordingly the music suffers, and she regrets this primarily for the sake of those friends who come almost every week for an evening of quartets or trios. But there are other recreations.

The Creek Mouse, for instance, a green canoe which in warm weather rides atop Mrs. Langer’s station wagon. Out driving, if she comes to a pleasing expanse of water, she will draw her automobile to the roadside, slide the Creek Mouse down from its rack, take it to the water’s edge and go for a paddle. Childhood summers spent at Lake George familiarized her with the niceties of handling a canoe. To laze along the shores of secluded, ponds and creeks, contemplating with a naturalist’s eye the undisturbed forms of life about her, is surely a happy pastime. Yet it does seem strenuous for a slightly built lady in her 70’s, doesn’t it?

“Not at all, really. The canoe weighs only 48 pounds and I can manage it quite easily. If you lift it by the center bar and let it ride against your hip as you walk, it’s rather like carrying a somewhat oversized child.”

The name? She laughed, facing light from the window—a light which seemed almost as much to emanate from her as to illumine the candid wrinkles and mercurial vividness of her expression. “It has a history, of course: At the seashore years ago I had a pram bow boat called the Sea Mouse, but a canoe doesn’t brave the sea. It’s only a Creek Mouse.”

Each summer, if a logical break in her writing presents an opportunity or if plain intellectual fatigue sets in, Mrs. Langer and a friend take Creek Mouse for a week of camping on some lake in the wildest wilderness she can find. She is an experienced camper and feels no apprehension whatever about spending days at a time far from civilization. A week’s break in her work does much toward recharging her mental energies. No longer period is needed nor could be spared from her demanding ambitions.

And yet one wonders. When the much-loved cello sits in its cabinet and Creek Mouse is idle atop the station wagon, when only the domain of ideas prevails in this place, one wonders what may be the ultimate satisfaction of living in it.

“I can’t answer that question,” said Mrs. Langer tersely. “It’s a purely intellectual matter. Perhaps the ability to meet difficult problems is my ultimate satisfaction. All of a sudden alight dawns on something which I’ve been wrestling with for a long time. This happens every few weeks. Then I’m very excited. I know I should stay and work it out completely, but I can’t. I get out my canoe or drive to Scarsdale to see my son and his family. I know I have the idea under control, but my excitement has to settle down before I can return to my desk. Whenever you know that you’ve broken through a difficult problem it gives you a great feeling of security. The greatest security in this tumultuous world is faith in your own mind.”

Such, then, seems to be the rationale for this solitary existence, with the living company of only aquarium pets and the squirrels, birds and occasional other animal inhabitants of the fields around the house. In this regard Mrs. Langer observed, “I find it very good to be surrounded by, and reminded of, forms of life that are not like ours. You grow very provincial if you think of all life only in terms of your own. One of the things on which I’m speculating is what animals feel. Somewhere in animal life are the forerunners of all those modes of feeling that come together in the human mind and only in the human mind. Some of these modes are highly specialized. For instance, the feeling which underlies all rational judgment is the feeling of logical conviction. Remember that by ‘feeling’ I mean everything that can be felt. This includes all mental acts and perceptions. Consequently, in this context ‘feeling’ is not something opposed to reason.”

Volumes II and III of her new book remain to be completed. The former will deal with what Mrs. Langer calls “The Great Shift”—the shift from animal mentality to human mind—while the latter will consist of two parts, one treating of “The Moral Structure” and the other “Of Knowledge and Truth,” that is, epistemology.

The writing will not wait. Mrs. Langer’s desk is overloaded with the work in progress, and the filing boxes with their thousands of meticulously filed, and annotated cards stand open and ready. One such card chosen at random reads:

Note—evolution and individuation. In centipedes each segment has a partly individual life. Kill the beast with a broom, and segments squirm all over the floor. The primitive organism is often semi-discrete—e.g., Volvox, essentially colonial, composite. But I can’t see centipedes as put together out of cooperative and social-minded segments. They were formed by differentiation. But it is interesting that this could go so far that when the parts are severed (as they easily are) each takes its own time about dying. When is “the centipede” dead?

To realize that even so seemingly trivial a circumstance as the demise of a centipede must occupy its own inevitable place in the supreme schema from which human awareness has issued is no less awe-inspiring than to contemplate any extraterrestrial exploit of that awareness. Accordingly Mrs. Langer’s apparently austere and secluded room is transfigured by the associative richness and humanity of its function.

The jonquil sunshine at the window, the tadpoles in their aquarium, the specific silences, the books, pictures and manuscripts, while Mrs. Langer folds and unfolds her evocative fingers, all seem conditions of her determination, and her ability, to articulate the means by which their separate being give life to the to the verifiable entelechy of our own. It is like music which, having ceased, yet prolongs spontaneously in our senses a rhythm and a resonance that communicate to the awareness an intimation of its incommensurable use. This in her slender, winning and indomitable person Mrs. Langer contrives to do. And much more. It is difficult to say, because she is difficult to understand. Still, she is understandable, because in her presence there is a life which lives with the imperative vitality of our own minds. And it is this living, all-embracing quality of mind which offers to redeem from ignominy and squalor the eventuality of human survival.

Langer main page