AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

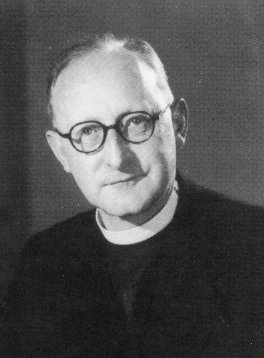

E. L. Mascall

1905-1993

From E. L. Mascall, Saraband: The Memoirs of E. L. Mascall, Herefordshire, UK: 1992, 378-383. I have taken the liberty of breaking up longer paragraphs into smaller units.

“. . . I have never thought of myself as an academic who found it convenient to be in holy orders but as a priest who, to his surprise, found himself called to exercise his priesthood in the academic realm.”

Anthony Flood

May 18, 2011

Epilogue

Je te salue, heureuse et profitable Mort

Ronsard

Whatever this book may be, it is not an apologia pro vita mea, for as I look back on my life the one thing that is clear is that I have had very little say in designing it. There have been critical moments when it was not at all obvious what I was meant to do next; but this was not because I was faced with an embarrassing variety of alternatives between which to choose but because, as far as I could see, nobody was particularly anxious that I should do anything at all; and when the way opened up again it turned out to be quite different from anything that I had imagined.

When I got a fairly good degree in mathematics at Cambridge, I hoped for an academic career, but not a single university post was offered me; and three years of teaching in a school convinced me that I was not meant to be a schoolmaster. When I became conscious of a call to the priesthood, I took this as meaning that I should be engaged in parish work for the rest of my working life; it was a complete surprise to be asked to assist in the training of ordinands at Lincoln. And when that came to an end, nothing could have seemed less likely than that I, whose sole academic training had been in mathematics at Cambridge, should be appointed to teach and research in theology at Oxford.

Truly, God moves in a mysterious way his won-ders to perform; but, while I am only too conscious of the handicap which I have suffered through a complete lack of the training which it had come to be assumed as proper and necessary for a future theologian to receive, I also discovered that the intellectual discipline in which I had been trained as a mathematician gave me an approach and an instrument of which theology was badly in need and which the accepted means of theological education not only did little to supply but, where some faint traces of it existed, could even do something to destroy.

Of course I did not see all this in a flash, but it gradually became more and more evident to me that most of what was taught in the academic faculties under the name of theology had little appeal or utility to those who were called to the Church’s pastoral and evangelistic work. There seemed, in short, to be a theological task for even as untrained and unconven-tional a theologian as I, and I located it as lying in the distinct but related areas of philosophical and of dogmatic theology. The reception which my books have received suggests that I was not mistaken. It should at least be clear that I have never thought of myself as an academic who found it convenient to be in holy orders but as a priest who, to his surprise, found himself called to exercise his priesthood in the academic realm.

Does this imply that my freedom as a scholar has been cramped or stunted by my religious commit-ment? Not in the least, if there is truth in the adage that grace does not destroy nature but perfects it, for the Christian theologian is not merely someone who has been trained in a certain investigative method and then turned loose to practice it upon the documents and institutions of Christianity; he is—or should be—living and thinking and praying within a great tradition. To quote some words from my inaugural lecture at King’s College, London, in 1962:

As I see it, the task of the Christian theologian is that of theologising within the great historical Christian tradition; theologizandum est in fide. Even when he feels constrained to criticise adversely the contemporary expres-sions of the tradition, he will be conscious that he is bringing out from the depths of the tradition its latent and hitherto unrecognised contents; he is acting as its organ and its ex-ponent. He will also offer his own contribution for it to digest and assimilate if it can. Like the good householder he will bring out of his trea-sure things new and old. But he will have no other gospel than that which he has received.1

There are, of course, many questions to which I do not profess to know the answers, about apparent contradictions between some elements in traditional Christianity and what are described as the assured results of modern scholarship; this does not seriously trouble me, as I have no particular right to expect answers to all my questions in this life; rather I am astonished to have been given answers to so many. What I am not prepared to do is to jettison the accumulated wisdom of the Christian ages in order to come to terms with what may well be a passing phase of critical scholarship.2 And although estab-lishments develop an infuriating capacity for blandly ignoring attacks that they cannot refute, there are at last ominous signs that the relativism and anti-supernaturalism which have dominated the study of Christian origins for nearly a century are crumbling from within.3

Throughout my active lifetime, however, the Church, in all its branches, has been subjected to a widespread and many-faced process of erosion, of which its leaders have been largely unconscious and to which, even when they have been conscious of it, they have often helplessly capitulated.

On the level of belief it consists of that relativistic view of truth and that naturalistic view of religion to which I have just referred; the extent to which it has gone is shown by the fact that, when recently an Anglican priest in an academic post, outstripping his colleagues who had denied the Trinity and the Incarnation, proposed to dispense with the existence of God, no formal rejection of his position ensued.

On the practical level it is shown by the tendency to make decisions by reference not to the teaching of Christ or the insights and traditions of Christendom but to the pressures of contemporary secularised society; the decision of the Episcopal Church in the U.S.A. about the ordination of women and the attitudes of various Anglican churches about the marriage of divorced persons are examples of this.

I sympathise deeply with my fellow Anglicans in the States in the catastrophe which has all but destroyed their church, and the more so because I believe they have simply been struck by the first wave of a storm which is breaking upon the Church as a whole, namely that of a radical relativism and naturalism. For the question which faces every Christian body to day and which underlies all individual practical issues is this: is the Christian religion something revealed by God in Christ, which therefore demands our grateful obedience, or is it something to be made up by ourselves to our own specification, according to our own immediate desires? When we assent, as I am convinced we must, to the first alternative, we must also insist that the second is not only false but bogus, and that our true fulfilment and happiness is not to be found by following our own whims but by giving ourselves to God in Christ, who has given himself for us. For, once again, grace does not destroy nature but fulfils it.

One bright feature in our present situation is the remarkable drawing together not only of Christians of liberal and undogmatic outlook—there is nothing surprising in that—but those of firm traditional allegiance, in bodies that have historically often been at daggers drawn. I recently discovered some quite prophetic remarks made as long ago as 1938 by an anonymous writer in the Quarterly Review of St Mary’s, Graham Street, a church which had acquired some notoriety as one of the more extreme centres of Anglo-Catholicism in London and certainly not suspected of sympathy for Protestantism. The writer was reviewing the Report entitled Doctrine in the Church of England, which had just been published, after fifteen years of intensive work, by a very mixed commission appointed by the two Archbishops in 1922. The reviewer remarked that

one of the most curious features of the docu-ment [was] the way in which Catholics, Evangelicals, and professed Modernists alike show[ed] themselves as tarred with the same brush,” namely, that “the great problem seemed to be to bring Christianity into step with the ‘march of mind,’ instead of . . . to rescue it from the flight from reason in which modern civilisation seems to be more and more involving itself . . . All alike come to the study of doctrine with the same presupposi-tions, and their naïve surprise at the measure of agreement they have found is in the circumstances rather comic. What however is not comic but pathetic,” [the reviewer con-tinued, and it is here that he became pro-phetic] is that there does exist today, as perhaps never before, as basis upon which Catholicism and Protestantism might find a point of departure for agreement, namely a profound belief in revelation and the supernatural; and this the Report hardly even considers.”4

Over forty years later those words have become strikingly true, in many places and in many ways. The document Growing into Union, produced in 1970 at the time of the Anglican-Methodist scheme is one example; the close relations between the Conser-vative Evangelical5 theological college at Oak Hill and the Roman Catholic Benedictine communities at Cockfosters is another; in the United States the movement named “Pastoral Renewal,” based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, has brought traditionally minded Catholics and Protestants together over a vast area; and individual contacts are widespread. In all this the key-words are “Revelation” and “the super-natural.”

There is of course plenty of theological liberalism about, and when reading some recent professorial utterances I hear not so much trumpet-calls for the world of the nineteen-eighties as echoes of the Cambridge of the nineteen-twenties. This has been reinforced by Roman Catholics, rejoicing in their post-conciliar freedom not always very responsible; both by them and by the ecclesiastical authorities there has been a tendency to repeat, though in a milder climate, the confusion which so bedeviled the Modernist controversy at the beginning of the century and to lump together the demand for a conscientiously exercised freedom of academic research with a radical rejection of revelation and the supernatural. This raises issues of tremendous practical importance at the present day, but I cannot discuss them here.

If the task of the Christian theologian is what I have suggested, the question inevitably arises not only whether it is being adequately performed in our academic institutions—I have rather firmly main-tained that it is not—but whether, as the nature of those institutions is currently understood, it possibly can be. The very impressive Jesuit thinker Fr. Bernard Lonergan has argued in his book Method in Theology that a necessary moment in the training of the Christian theologian is a costing and irrevocable conversion, which must take place on the intel-lectual, the moral and the religious plane. His authoritative interpreter Fr. Frederick Crowe, S.J., in his book The Lonergan Enterprise presses the point home ruthlessly:

Do I allow questions of ultimate concern to invade my consciousness, or do I brush them aside because they force me to take a stand on God? With such questions we are being forced to the roots of our own living, challenged to discover, declare, and, if need be, to abandon our horizon in favour of a new one in which our knowing is transformed and our values are transvalued. We are also abandoning the neutral position of an observer, and entering another phase of study altogether.6

Fr. Crowe also insists that the required renewal of theology and philosophy cannot come about through our existing academic institutions:

Can you even imagine, much less contemplate as a serious proposal, inviting your university colleagues to a discussion and informing them casually that the spirit of the meeting would be a prayerful one, and that a good part of the input would be the self-revelations of your interior spiritual life and theirs? . . . In any case there would be the problem of a state-supported university in a secular state sponsoring such activities. Still negatively, the average theological congress will not be the vehicle for this theology—for the same reason that applies to the university, and for the additional reason that the average congress is described, with a degree of exaggeration but with a grain of truth, too, as a dialogue of deaf persons. One goes there to get off one’s chest the ideas that no one back home will listen to; no one at the congress listens, either, but the speaker is not so acutely aware of it.7

Fr. Crowe suggests that what is needed is a theological centre on the model of the retreat-house:

A theological centre modeled on that would be a place of prayerful and thoughtful quiet to which theologians could retire, not just for two days or a week, but for forty days of retreat from offices and deans’ schedules and committee meetings on tenure. They could do theology together in a contemplative mood. Nor would I exclude congresses of shorter duration, provided they are not the “average” type I just mentioned.8

This, it is stressed, still leaves the university with a vital theological role:

In addition to providing the academic setting for critical scholarship, the first phase and its tasks, as it has been doing for some centuries, it will also be the ordinary vehicle for the interdisciplinary discussions which are a part of systematics and communications. These are discussions without which theology cannot mediate between a religion and a cultural matrix.9

Whether there is any real prospect of a radical renewal of the theological enterprise on these lines may indeed seem doubtful, as much perhaps on temperamental as on material grounds. But for myself I can only say this, that, while I am deeply sensible of the tolerance and sympathy which I have received from the academic faculties in which I have worked, the Christian Faith and the Christian Church have been the source from which my inspiration as a theologian has been drawn. I have used the phrase Theologizandum est in Fide, and I would now add the words in Ecclesia, in Liturgia.

Finally, remembering that great master who declared shortly before the end of his earthly pilgrimage that he could write no more because that had been revealed to him compared with which all that he had written was as a straw, I look to the day when, in the words of a possibly even greater master, “all our activity will be Amen and Alleluya.”

Notes

1 Theology and History, p. 17.

2 Thus, for example, the proposal to abandon St John’s Gospel as a source of Christian teaching because of the theory that it is a gnostic fiction is to my mind quite outrageous.

3 See, e.g., Patrick Henry, New Directions in New Testament Study, 1979.

4 St Mary’s Graham Street Quarterly Review, Spring 1938, p. 41.

5 I must put in a word of protest against the frequent dismissal of Conservative Evangelicals as “funda-mentalists,” in the pejorative-sense of that flexible term. Some no doubt are, but others are as certainly not.

6 The Lonergan Enterprise, p. 57.

7 Ibid., p. 95.

8 Ibid

9 Ibid p. 96