AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

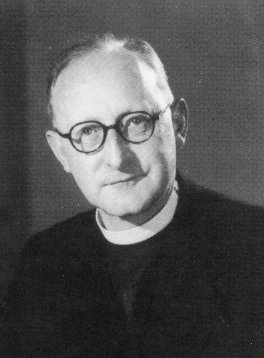

E. L. Mascall

1905-1993

Reformatted from text taken from here. First published September 1972; second edition, June 1977. For greater ease of reading, I have broken up some larger paragraphs.

Posted April 30, 2011

Women Priests?

E. L. Mascall

In discussing whether women should be ordained to the priesthood or not it will be well, for the sake of clarity, to make some preliminary points.

First of all, it must be recognised that two quite distinct questions are involved, though once their common existence and their mutual distinctness have been accepted it will for the most part be possible to discuss them together. The former is whether it is possible for women to be priests, the latter is whether it is right and desirable for them to be priests; and unless the former is answered in the affirmative the second cannot arise.

This is important, because it is frequently assumed without argument that a woman upon whom the traditional rites of ordination to the priesthood have been performed by a bishop will undoubtedly have become a priest, so that the only questions remaining to be discussed are ethical ones (Is it not unjust to withhold the priesthood from women?) and pastoral ones (Will not women perform the traditional duties and functions of the priesthood just as efficiently as men?).

Secondly—and this is closely connected with the first point—it must be stressed that what we are concerned with is the Catholic priesthood, as that has come down to us in the great episcopal communions of East and West, and not with the various forms of ministry that exist in the Protestant churches and communities.

In saying this, one is not adopting an attitude of contempt or unfriendliness to our separated brethren but simply recognising the fact that the Catholic conception of the ministry is different from the Protestant conception, even if the Catholic conception includes the Protestant conception as an element in itself, and even if—as is undoubtedly the case—the Catholic conception is itself undergoing today a great deal of re-examination and development.

We shall see later on that on one understanding of the nature of the ministry in Protestantism the ordination of women is no less abhorrent than it is in traditional Catholicism and Orthodoxy. It is indeed doubtful whether there is one basic doctrine of the ministry held throughout Protestantism, of which the views of the different denominations are merely variants. When, for example, the late Paul Tillich wrote: “There are in Protestantism only laymen; the minister is a layman with a special function within the congregation . . . . He is a non-layman solely by virtue of his training,” he was not merely contradicting himself verbally by saying first that a minister is a layman and then that he is not; he was expressing a view of the ministry quite contrary to that of many Protestants, who would hold that what makes a minister is neither his training nor his choice by a congregation but his call by God.

The point remains that, on Tillich’s view and no doubt on some other Protestant views as well, there is nothing impossible in a woman becoming a minister, for she is just as capable of undergoing a course of training as a man. I must add that I do not despair, as ecumenical dialogue proceeds, of Catholics and Protestants coming to a common understanding of the Church’s ministry. What I do maintain is that they have not come to it yet, and that discussions about the ordination of women, as of other matters connected with the ministry, frequently reach a condition of frustration through lack of agreement about what the ministry is and sometimes through the lack of any clear conception about the ministry at all.

This point can be illustrated by the decision of the established Church of Scotland to open its ministry in principle to women. This was announced by the newspapers, no doubt in accordance with the tenor of the preceding debates in the General Assembly, under such headlines as “Pulpits now open to Women” and “Women now allowed to preach.” Now I do not deny the importance of preaching as a function of the ordained minister nor do I suggest that Presbyterian ministers never celebrate the sacraments, but it will, I think, be clear that the nature of the debate and the grounds of decision are likely to be very different in a church in which sermons are preached every Sunday but the Lord’s Supper is usually celebrated only once a quarter from what they will be in a church in which the Holy Eucharist is celebrated weekly or even daily. In the former case the primary question will be “Should women be commissioned to preach the word of God?,” in the latter it will be “Should (or can) women be ordained to celebrate the Eucharist?,” and it will be well to bear this difference in mind when consulting such statistics as those given in a recent number of Concilium about the practice of various churches in the matter, since it is logically possible to give an affirmative answer to the former question and a negative one to the latter.

It is furthermore important not to misunderstand the suggestions (in some cases even the demands) emanating from certain Roman Catholic circles for the ordination of women to the priesthood. Some of these rest upon no theological basis at all and are merely typical of a temperamental desire to destroy all the inherited structures of the Church and to assimilate the Catholic religion to the trends and outlooks of the contemporary secularised world.

Some of them, however, manifest a praiseworthy wish to give the Church’s life a wider and firmer foundation than that of post-Tridentine scholasticism. It is important to remember that it is a common practice in the Roman Catholic Church to question the truth of a statement or the legitimacy of a practice in order to elicit the fundamental reasons for the truth or the real grounds of the practice; thus, to give a famous example, St. Thomas Aquinas in the Summa Theologiae raised without qualms the question whether God exists.

In a communion in which nothing is likely to be upset overnight there is a lot to be said for this method; it is well exemplified by the resolution which was submitted by Cardinal Flahiff to the Synod of Bishops in Rome in October, 1971, on behalf of the bishops of Canada, urging the immediate establishment of a mixed commission to study in depth the question of the ministries [sic] of women in the Church. While it was understood that this did not exclude the question of the priesthood (and indeed no comprehensive study could), it was emphasised that there was no desire to prejudge the question or to make recommendations as to time or mode of further action.

There is thus no justification for Anglicans to urge such Roman stirrings as providing an example for precipitate imitation, or for saying “Rome is going to ordain women, so let us get in first.” This is not, however, the first case in which the tentative reopening of a question by Roman Catholic bishops or theologians has been taken by over-enthusiastic Anglicans as an invitation to jettison traditional positions of doctrine or practice.

The State of the Question

In assessing the present situation it is perhaps well to recall that in 1962, following the publication of a report with the rather odd title Gender and Ministry (odd because “gender” has usually been taken as a grammatical and not an anthropological term) which had been prepared by a working-party of the Central Advisory Council on Training for the Ministry (CACTM), the Church Assembly requested the Archbishops of Canterbury and York “to appoint a Committee to make a thorough examination of the various reasons for the withholding of the ordained and representative priesthood from women.”

In response to this the two Archbishops appointed a Commission with the simpler terms of reference “to examine the question of Women and Holy Orders.” This Commission produced a report which was published in December, 1966, under the title Women and Holy Orders. It refrained, probably wisely, from making any recommendations but confined itself to assembling a large amount of historical material and setting out the arguments which had been urged both for and against the ordination of women to the priesthood. In July, 1967, the Church Assembly rejected a resolution welcoming the further consideration of the matter by the Advisory Council for the Church’s Ministry (ACCM, the successor of CACTM), the Council for Women’s Ministry in the Church and the Joint Committee of Representatives of the Church of England and the Methodist Church and describing itself as “believing that there are no conclusive theological reasons why women should not be ordained to the priesthood but recognising that it would not be wise to take unilateral action at this time.”

The Methodist Conference, the supreme governing body of the Methodist Church in this country, had already, in 1966, affirmed its conviction “that women may properly be ordained to the Ministry of the Word and Sacraments” but, “recognising that it would not be wise to take unilateral action at this time”, expressed a desire for discussions with representatives of the Church of England. This discussion took place and its results were published in May, 1968, under the title Women and the Ordained Ministry. With an eye on the Anglican/Methodist union scheme this report expressed the view that unilateral action by the Methodist Church would not be an insurmountable barrier to Stage One of the Scheme but, unless the Church of England had decided to ordain women, might well hinder the implementation of Stage Two.

This piece of domestic history can have been of little direct interest to most of the members of the 1968 Lambeth Conference, but the general question must have been present to their minds. The subcommittee on Women and the Priesthood, while expressing great respect for the opposite view, came down unhesitatingly in support of the ordination of women; it found “no conclusive theological reasons for withholding ordination to the priesthood from women as such.” It did indeed assert:

The appeal to Scripture and tradition deserves to be taken with the utmost seriousness. To disregard what we have received from the apostles, and the inheritance of Catholic Christendom, would be most inappropriate for a Church for which the authority of Scripture and tradition stands high.

Nevertheless, the appeal to Scripture was dismissed by juxtaposing two passages from St. Paul, one of which would, if anything, count against the ordination of women while the other has no explicit relevance to it. Similarly, the appeal to tradition was dismissed without detailed argument on biological and sociological grounds. It was added that “the element of sexuality in the Godhead and its implication for the sex of the priesthood are complex and debatable matters,” but the sub-committee felt itself competent to solve these complex and debatable matters in nine lines. The rest of the sub-committee’s report makes no reference to matters of principle but contents itself with asserting that churches which have ordained women have been satisfied with the results.

It is difficult to discover whether the matter received really adequate discussion in the crowded and hurried conditions of the Conference’s full sessions. In Resolution 34 it “affirm[ed] its opinion that the theological arguments as at present presented for and against the ordination of women to the priesthood are inconclusive.” The addition of the words “or against” might seem significant. The Conference made it plain, however, in its subsequent resolutions that this state of alleged theological inconclusiveness was not to be taken seriously and that action could be envisaged on the assumption that the arguments against were valueless and that only the arguments for were valid. It asked all the parts of the Anglican Communion to give careful study to the question and to report their findings to the Anglican Consultative Council (ACC), which would make them generally available. The ACC was also asked to initiate consultations with other Churches, both those which did and those which did not ordain women, and distribute the information thus secured.

The Conference also requested that any Anglican national or regional Church or province contemplating ordaining women to the priesthood should seek and carefully consider the advice of the ACC (Resolutions 35–37). This last request is indeed surprising, for in it the Bishops of the Anglican Communion were shifting their responsibility, in a major matter affecting the basic structure of the Church, to a body of somewhat haphazard constitution which at the time of Lambeth 1968, had not even come into existence. When the ACC in fact came into existence and met in February and March, 1971, at Limuru in Kenya it consisted of fifty-one persons, bishops, priests and lay-people, each of the member churches of the Anglican Communion contributing two or three. The only ex officio member was the Archbishop of Canterbury. In spite of Resolution 37 of Lambeth 1968, it is difficult to see that advising about the ordination of women falls within the eight functions which Lambeth itself assigned to the ACC when it constituted it in Resolution 69. It is certainly difficult to see that all the members of the ACC had the necessary qualifications to consider such a matter in more than a pragmatic or emotional way. However, even setting such doubts aside, the resolution, No. 28(b), which was passed at Limuru has some very peculiar features. It was passed by 24 votes to 22 in the following terms:

In reply to the request of the Council of the Church of Southeast Asia, this Council advises the Bishop of Hong Kong, acting with the approval of his Synod, and any other bishop of the Anglican Communion acting with the approval of his Province, that, if he decides to ordain women to the priesthood, his action will be acceptable to this Council; and that this Council will use its good offices to encourage all Provinces of the Anglican Communion to continue in communion with these dioceses.

There is a very serious ambiguity about the phrase “this Council” in this resolution. Does it mean the fifty-one persons present at Limuru from February 23rd to March 5th, 1971, or does it include any future meetings of the ACC? If the former, it is impossible for “this Council” to use its good offices or do anything else after the latter of these dates, since it will then no longer exist, and if it is suggested that the individual members will find the proposed action acceptable and use their good offices, this is very doubtful, since just under half the members voting did in fact vote against the resolution.

If, on the other hand, “this Council” is intended to include future meetings of the Council, with, in all probability, a largely different membership, the resolution is surely ultra vires, since no authority has been given to the members of the ACC in 1971 to bind their successors for ever and it would need a shift of only two votes for the resolution to be rescinded. No one, I think, has suggested that decisions of the ACC, like ex cathedra papal pronouncements, are irreformable of themselves and not by the consent of the Church. And indeed it would seem rash in the extreme for any part of the Anglican Communion to rely upon such fragile and tenuous assurances. This is not just a debating point, but involves a matter of serious principle. Have the bishops of the Anglican Communion handed over their responsibility in the matter of the ordination of women to a bare majority of such an amorphous and fluctuating assembly as the Anglican Consultative Council?

At least one bishop appears to think so, for on Advent Sunday, 1971, the Bishop of Hong Kong went through the form of ordaining two women to the priesthood, in spite of the fact that the Archbishop of Canterbury had asked that no bishop should so act before all the Anglican provinces had stated their views. His Grace had been quoted several times as saying that ordination of women to the priesthood would ultimately come but that the time had not yet arrived; clearly the Bishop of Hong Kong disagreed on this latter point and saw no reason to accept the Archbishop’s plea for delay. In any case, the ACC at Limuru, in Resolution 28(a), has asked all the Anglican Churches to express their views in time for its next meeting in 1973, so there would seem to be, at any rate in the ACC’s own opinion, some urgency in the matter.

Scripture and Tradition

In any other matter than this the argument from Scripture and Tradition would be considered overwhelming. The words which I have quoted above from the Lambeth sub-committee could hardly have been stronger:

The appeal to Scripture and tradition deserves to be taken with the utmost seriousness. To disregard what we have received from the apostles, and the inheritance of Catholic Christendom, would be most inappropriate for a Church for which the authority of Scripture and tradition stands high.

This, one might think, would have disposed of the matter. It is therefore little less than astonishing to find the sub-committee dismissing both Scripture and tradition in two brief paragraphs in a way that, by its own standards, is most inappropriate and which certainly does not manifest the utmost seriousness.

All that is said about Scripture is this:

Nevertheless the data of Scripture appear to be divided on this issue. St. Paul’s insistence on female subordination, made to enforce good order in the anarchy at Corinth, is balanced by his declaration in Gal. 3, 28, that in the one Christ there is no distinction of Jew against Gentile, slave against free man, male against female.

That is all—not a word about the highly theological exposition in Ephesians V, in which the relation of man to woman is compared with that of Christ to the Church, and not a word about the attitude and teaching of Christ himself. Those who advocate the ordination of women usually start from the undeniable fact that, whereas in Judaism women occupy an essentially inferior position, if for no other reason that they are physically unable to be admitted into the Covenant by the rite of circumcision, in Christianity the water of baptism and the unction of the Spirit are available indifferently to men and women alike. The bearing of the argument is, however, all the other way. For it is the same primitive Church which is appealed to as witnessing to the absolute equality of all Christians, both male and female, in their status as members of the Body of Christ through baptism, which restricted the Church’s ministerial functions to men.

Behind the action of the Church in this matter there lies the example of her Founder, who (as we see for example in his condemnation of the Jewish attitude to divorce) was full of sympathy for women but who nevertheless founded the Church’s ministry by giving it a purely male apostolate. It would be absurd to suppose that in doing this Christ was depriving women of their legitimate rights, and misleading his Church as to their true status, as a concession to the conventions and prejudices of the time; even his enemies never accused him of conventionality and cowardice and it would ill become his disciples in the twentieth century to do so. When we find our Lord and the primitive Church restricting the ministry to males in spite of the emphasis laid by both alike on the absolute equality of men and women as members of the New Israel which is the Body of Christ, is it not prudent to assume that there must be some very deep and significant reason in the nature of things for this restriction?

The following paragraphs from the chapter on the Case against the Ordination of Women to the Priesthood in the report Women and Holy Orders deserve to be quoted at length; nothing in the subsequent chapter putting the opposite case seems to me to answer them:

(a) It would be contrary to the tradition of the Church, from the time of the Apostles. If it is to be maintained that that tradition is wrong it has to be demonstrated, either that the Apostles failed to divine or to implement the intention of Christ, if he intended women to partake in the priestly ministry, or that Christ erred in not declaring this to be his intention. Neither proposition can validly be maintained. It is therefore quite legitimate to assert that the exclusion of women from Holy Orders is just part of the nature of things, in this case of the nature of the Christian Church.

(b) The conviction that the priesthood can only be male is supported by the deliberate inclusion by Christ and the Apostles of women with men in the wider priesthood of the whole Church. There is a general priesthood of the whole people of God, comprising men and women, and a specific priesthood of those who have been ordained to it. The wider priesthood of the Laos indicates that if the ministerial priesthood is composed only of males, this is in the divine ordinance as much as the existence of the Church itself. If only secondary difficulties stood in the way, the ministry could easily have been opened to both sexes.

(c) Allied to this argument is that based on the recognition that Christianity was a revolutionary religion, not least in the greatly heightened esteem and value accorded to women . . . . The maleness or the Christian priesthood must therefore have deeper grounds than mere conservatism or a poor estimate of the feminine nature.

(d) All theistic religions (that is to say, religions in which the God or Gods transcend the created order and stand behind nature and history, as well as acting in them, rather than being merged in a monistic or pantheistic unity) have male priesthoods. Female priesthoods belong to the nature religions in which human nature is sensed to be merely part of society, society part of nature, and nature itself Divine. The Christian Church, rooted in the biblical view of God and his relation to the world, has without question adopted a male priesthood. It is therefore pertinent to ask whether the feature of a male priesthood can be modified by the addition of a female priesthood without altering the essential character of the Christian ministry, and without affecting the human psyche at those deep levels at which it responds to religious symbolism.

None of these considerations appears to have made any impression on the Lambeth sub-committee, which indeed shows no signs of having heard of them. After the summary dismissal of Scripture to which I have referred above, it deals with tradition as follows:

It appears that the tradition flowing from the early Fathers and the medieval Church that a woman is incapable of receiving Holy Orders reflects biological assumptions about the nature of woman and her relation to man which are considered unacceptable in the light of modern knowledge and biblical study and have been generally discarded today. If the ancient and medieval assumptions about the social role and inferior status of women are no longer accepted, the appeal to tradition is virtually reduced to the observation that there happens to be no precedent for ordaining women to be priests. The New Testament does not encourage Christians to think that nothing should be done for the first time.

In the absence of any details it is difficult to assess the force of these references to biology and sociology, but in order to make a case for the abandonment of the unvarying tradition of the Church we should need answers to the following questions:

(1) What, if any, were the false biological views in question?

(2) How did it follow from them that women could not be ordained to the priesthood?

(3) What are the views which have taken their place?

(4) Do those views imply that women can be ordained to the priesthood?

(5) In what ways were women in the past believed to be socially inferior?

(6) Did this belief imply that women could not be ordained to the priesthood and if so, how?

(7) Have the views about women which have now come to he held been proved to be true?

(8) If so, do they imply that women can be ordained to the priesthood?

All these are serious questions and the matter is not to be dealt with by casual reference to biology and sociology. Even if the refusal to ordain women in the past rested on a false belief in their inferiority (and it is doubtful whether this has been proved), there may still be other reasons against their ordination. In any case I would suggest that all this talk about inferiority and inequality is really irrelevant and un-Christian. For the basic fact about the sexes is not that they are inferior or superior to each other but that they are different.

The Difference of the Sexes

Supporters of the ordination of women frequently point to the alleged injustice of the exclusion of one half of the human race from the status and functions of priesthood. There will be something to say later about this assumption that priesthood is a status that can be possessed as a right, but it may be relevant to remark that there is already a status and function from which one half of the human race is constitutionally and incurably excluded, namely that of motherhood. And if it is true that the order of redemption is not isolated from the order of creation and that grace does not ignore or destroy nature but presupposes and perfects it, it would be very strange if the differentiation of function on the level of nature was not paralleled by a not less marked differentiation of function on the level of grace.

One of the results of the modern tendency to emphasise the idea of equality rather than that of differentiation is the type of feminism which by demanding the same functions for women as for men implicitly assumes the superiority of male status. If women want to be as like men as possible, this can only mean that manhood is essentially superior to womanhood. This is not a view that any Christian should accept; its basic absurdity is seen in the recent demand by a member of the Women’s Liberation Movement that women should refuse to bear babies any more and that scientists should immediately perfect the technique of growing babies in test-tubes.

The chapter in Women and Holy Orders from which I have previously quoted makes this point clearly and with restraint:

(e) The assertion that the ordination of women is the logical outcome of a steadily growing recognition of woman’s full humanity is fallacious. A philosophy of social evolution making for this kind of equivalence of women with men has no backing in historical, philosophical, biological or religious theory.

(f) Western civilisation has witnessed a hypertrophy, a morbid enlargement, of its masculine aptitudes, and the feminist movement, by bringing women into the characteristic masculine way of handling life, has aggravated the disease. The characteristics of the two sexes must be regarded as complementary. In the concrete, for the art of living, there are male and female aptitudes. A refusal to recognise this polarity of the sexes tends to create not satisfaction, but further and more deep-seated restlessness.

(g) The view that sex is irrelevant in deciding who should or should not be ordained to the priesthood has been based on a belief that there is a sexless human nature common to men and women underlying their sex differences. This view is no longer tenable. There is in fact a masculine and a feminine human nature with some complication from the shadow of the opposite sex in each.

Like other advocates of female emancipation, the proponents of the ordination of women are not always consistent in their arguments, which oscillate between at least three positions.

The first is that women are in all the essential features identical with men and so have just as much right to ordination as men have.

The second is that women are so different from men that an exclusively male priesthood cannot be fully representative of humanity.

The third is that men have certain female characteristics and women have certain male ones, so that there is really only a difference of degree between the two; this is sometimes accompanied by the assertion that there is a maternal component in the fatherhood of God.

The third argument has been advanced a good deal in recent years, but it would seem to lead to the opposite conclusion than that intended. For if it is true that the essential features of each sex are to be found in the other, then a male priest will be able to manifest in his pastoral relationships not only the male features but the female as well. The truth seems to be that there are many characteristics that are common to both sexes simply because they are both human, and many other characteristics that are proper only to one; but if we start by saying that female characteristics are to be found in men and male characteristics in women, we shall probably end up in a state of verbal confusion in which we shall find it difficult to maintain the distinction between male and female characteristics at all. It will be well to turn now to considerations of a more definitely theological kind.

Theological Considerations

As we have already seen, the Lambeth Conference of 1968 “affirm[ed] its opinion that the theological arguments as at present presented for and against the ordination of women to the priesthood are inconclusive” (Resolution 34). One might have thought that, if the arguments were as evenly balanced as that, there was, to say the least, insufficient justification for rejecting the age-long tradition of the Church; there would seem to he at least a prima facie case against making any drastic change. This was not, however, the Conference’s conclusion.

It is pertinent to ask, though there is little prospect of finding an answer, what the Conference supposed a conclusive theological argument would be. In common with most argumentation outside the purely abstract realm, theological arguments very rarely take the form of simple Aristotelian syllogisms. In the present case we have a consistent tradition of the Church going back to the very earliest times, and certain truths of faith which are closely coherent with that tradition and throw considerable light upon it. Though the Lambeth resolution did not mention these, the sub-committee did, though once again it combined verbal reverence with practical dismissal:

The element of sexuality in the Godhead and its implication for the sex of the priesthood are complex and debatable matters. We acknowledge God as father and we worship the incarnate Lord as man. No theologian has ever understood this to mean that God is male. There is great significance in the ancient imagery of the bishop or priest as father to his family or as representing Christ the bridegroom to the Church his bride. This is an image of unquestionable value, a profound pointer to the truth. But the truth to which it points has been expressed with equal power by St. Paul in referring to his own relation to the Galatian church as that of a mother again in travail with her children.

And the sub-commission asks the question, obviously expecting the answer No: “In view of the above considerations, are we to conclude that it nevertheless inheres in the very nature of the Gospel that women are intrinsically incapable of receiving ordination to the priesthood?”

“Great significance”, “of unquestionable value”, “profound pointer to the truth”—these are strong phrases indeed. They are nevertheless followed by the assertion, for which no further support is advanced than one sentence from St. Paul, the metaphorical sense of which is obvious, that in all relevant respects fatherhood and motherhood are identical.

Once more we see doctrinal considerations treated as Plato in the Republic wished to treat the poet: “we shall do obeisance to him as to a sacred, wonderful and agreeable person, . . . and we shall anoint him with myrrh and crown him with a wreath of sacred wool and send him off to another city”, for “we shall say that we have no such man in our city.” I should like at this point to draw attention to a paper entitled “Priestesses in the Church?” by the late C. S. Lewis, which is included in the posthumously published volume Undeceptions.

Lewis begins by admitting that at first sight all the rationality is on the side of the innovators. “We are short of priests. We have discovered in one profession after another that women can do very well all sorts of things which were once supposed to be in the power of men alone . . . . And against this flood of common sense, the opposers (many of them women) can produce at first nothing but an inarticulate distaste, a sense of discomfort which they themselves find it hard to analyse.” However, “that this reaction does not spring from any contempt for women”, Lewis significantly goes on to point out,

is, I think, plain from history. The Middle Ages carried their veneration for one Woman to a point at which the charge could plausibly be made that the Blessed Virgin became in their eyes almost “a fourth Person of the Trinity.” But never, so far as I know, in all those ages was anything remotely resembling a sacerdotal office attributed to her. All salvation depends on the decision which she made in the words Ecce ancilla; she is united in nine months’ inconceivable intimacy with the eternal Word; she stands at the foot of the cross. But she is absent both from the Last Supper and from the descent of the Spirit at Pentecost. Such is the record of Scripture. Nor can you daff it aside by saying that local and temporary conditions condemned women to silence and private life. There were female preachers. One man had four daughters who all “prophesied”, i.e., preached. There were prophetesses even in Old Testament times. Prophetesses, not priestesses.

“At this point”, Lewis continues, “the common sensible reformer is apt to ask why, if women can preach, they cannot do all the rest of a priest’s work. This question deepens the discomfort of my side.” But “the more they speak (and speak truly) about the competence of women in administration, their tact and sympathy as advisers, their national [sic, qu. natural?] talent for visiting, the more we feel that the central thing is being forgotten.” That thing is priesthood.

Sometimes the priest turns his back on us and faces the East—he speaks to God for us: sometimes he faces us and speaks to us for God. We have no objection to a woman doing the first: the whole difficulty is about the second. But why? Why should a woman not in this sense represent God? Certainly not because she is necessarily, or even probably, less holy or less charitable or stupider than a man . . . . The sense in which she cannot represent God will perhaps be plainer if we look at the thing the other way round.

Suppose the reformer stops saying that a good woman may be like God and begins by saying that God is like a good woman. Suppose he says that we might just as well pray to “Our Mother which art in heaven” as to “Our Father.” Suppose he suggests that the Incarnation might just as well have taken a female as a male form, and the Second Person of the Trinity be as well called the Daughter as the Son. Suppose, finally, that the mystical marriage were reversed, that the Church were the Bridegroom and Christ the Bride. All this, as it seems to me, is involved in the claim that a woman can represent God as a priest does.

“Now it is surely the case”, Lewis concludes, “that if all these supposals were ever carried into effect we should be embarked on a different religion. Goddesses have, of course, been worshipped: many religions have had priestesses. But they are religions quite different in character from Christianity.”

There is only one place in which I would question Lewis’s argument, but to strengthen rather than to weaken it. I am not sure that the priest speaks only to man from God and not also to God from man. It might, however, be replied that speaking to God from man, while it is a priestly function, is proper to the whole Church as the priestly body of Christ the great High Priest, even if its public and liturgical expression must be made through the ordained minister. Whatever may be true about this, the speaking to man of the reconciling word of God is an inherently personal and ministerial act. All Christian priesthood is the priesthood of Christ, whether exercised directly in his earthly life or mediately through his ordained ministers; and ministerial priesthood, as Moberley made clear in his great work bearing that name, is an essentially personal activity.

No doubt God in his omnipotence might have redeemed us by a sheer exercise of his infinite power and, so to speak, have wrenched us back into the shape which he wishes us to have. Nevertheless, God is personal—three Persons, united in one divine life—and we are persons; and he deals with us in accordance with his nature and ours. So the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, God the Son, took our human nature, so that he might live among us, a Person among persons, living, as one of us, that personal life of obedience and love to God the Father which culminated in a perfect human death and led through that death to a transformed and glorified, but still human and personal, life; teaching, healing, forgiving, consoling, strengthening those who came into contact with him, and always as a Person dealing with persons. God made man, the Son of God living a human life as a Person, living among persons and ministering to them as persons, this is the method that God chose to redeem the world; and the price of that method is shown by the Cross.

And when, after his Ascension, the Redeemer was no longer to be seen, heard and handled by our physical senses, he had already made provision that the ministry which he had exercised as a Person to persons should continue to be exercised by him through persons to persons. So he called and trained and commissioned and equipped twelve men whom he named apostles—persons sent—not just to be persons who would act instead of him but persons through whom he himself would act. So the sacramental and pastoral ministry of the Church through the ages, just because it is the ministry of the Person Jesus to persons for whom he gave his life, is exercised through persons, and through persons who are not just his representatives, not even just his agents, but the very organs through whom he himself acts. If there is this essential identity between the ministry which Jesus exercised in his earthly life and that which he now exercises in his Church, it is, to say the least, highly congruous that the manhood through which he acts should be male as he is male, whatever may be metaphysically possible to the sheer potentia absoluta of infinite Deity. But now to return to C. S. Lewis, after this lengthy but not irrelevant digression.

To the assertion that, if the masculine terms of religion, Father, Son and Bridegroom, were changed into the feminine terms, Mother, Daughter and Bride, we should have a different religion Lewis imagines “common sense” objecting “Why not? Since God is in fact not a biological being and has no sex, what can it matter whether we say He or She, Father or Mother, Son or Daughter?” Lewis’s reply to this is that the Christian religion is in fact based on what God has said and done:

Christians think that God Himself has taught us how to speak of Him. To say that it does not matter is to say either that all the masculine imagery is not inspired, is merely human in origin, or else that, though inspired, it is quite arbitrary and unessential. And this is surely intolerable: or, if tolerable, it is an argument not in favour of Christian priestesses but against Christianity. It is also surely based on a shallow view of imagery . . . a child who had been taught to pray to a Mother in Heaven would have a religious life radically different from that of a Christian child.

Thus, Lewis continues, “the innovators are really implying that sex is something superficial, irrelevant to the spiritual life. To say that men and women are equally eligible for a certain profession is to say that for the purposes of that profession their sex is irrelevant.” To raise questions about the “equality” of the sexes is really pointless. “Unless ‘equal’ means ‘interchangeable,’ equality makes nothing for the priesthood of women. . . . One of the ends for which sex was created was to symbolise to us the hidden things of God. One of the functions of human marriage is to express the nature of the union between Christ and the Church. We have no authority to take the living and sensitive figures which God has painted in the canvas of our nature and shift them about as if they were mere geometrical figures.”

Lewis’s discussion is all the more impressive coming as it does from a writer who was very little concerned with bloodless abstractions and was highly sensitive to the mysteries and depths of human nature as God has created and redeemed it. And to him there was something superficial and undiscriminating in the concept of humanity, even on the natural level, that lay behind demands for the ordination of women to the priesthood. “With the Church” he wrote, “we are farther in: for we are dealing with male and female not merely as facts of nature but as the live and awful shadows of realities utterly beyond our control and largely beyond our direct knowledge. Or rather, we are not dealing with them but (as we shall soon learn if we meddle) they are dealing with us.”

A Voice from Protestantism

Very similar in some respects to Lewis’s discussion is a very remarkable paper by the Calvinist theological Professor Jean-Jacques von Allmen of Neûchatel. In view of my earlier stress upon the fact that we are concerned with the Catholic priesthood and not with various concepts of the Protestant ministry it will be well to make two points.

First, von Allmen is a very high-church Protestant indeed, as anyone who has read his great book Worship will have discovered; there is no trace in him of Tillich’s view that a minister differs from a layman only by his training. On the contrary,

the pastoral ministry is that grace, which the Lord has willed for the Church and instituted in the Church, by which one of the faithful, following on the Apostles, is called to act in the name of Christ the prophet, Christ the priest (sacrificateur) and Christ the King. . . . It is by the power of the Holy Spirit, invoked upon him at his ordination, that he is justified in exercising this ministry in the Church, and that he presumes to exercise it with confidence.

Secondly, Calvinism has, of all forms of Protestantism, when it is true to its origins and traditions, the strongest sense of’ the Church as an organic and structured reality.

Von Allmen begins by stressing “the fact that in the Church everything is grace.” “No one,” he writes, “men no more than women, has the right to be a pastor. . . .”

You condemn yourself to never solving the problem when you say that it is unjust that women have not, as men have, the right to be a pastor; it is a grace which has not been purposed for them, because it would divert them from their being and their vocation, just as the grace of motherhood, for example, could not be given to a man.”

“Every ministry”, he asserts, “is a grace. It does not depend then in the first place on the Church, but on the Lord of the Church; and if he has willed that among the ministries that of the pastor is to be reserved for men, the Church consequently has not the right to oppose this will by disobeying.”

Von Allmen has a refreshingly independent attitude to the contemporary climate of opinion:

It could not be a question of progressive adaptation or reactionary obstinacy, for we are not called upon to comply with the present age, either in respect of what impels it forward or what restrains it; it is simply a question of obedience or disobedience, of faithfulness or unfaithfulness.

It becomes clear later that this does not mean that God acts arbitrarily, without respect for the nature which he has given to mankind. Three major sets of arguments are given against the ordination of women to the pastoral ministry; the first is described as ecclesiological, the second as both anthropological and eschatological, and the third as ecumenical.

The ecclesiological argument replies to the assertion that, since women are admitted to faculties of theology and follow the same courses, offer the same work and pass the same examinations as men, they must be given the chance to practise the same profession. This assertion, von Allmen comments, assumes that

the pastoral ministry is not so much an institution of the Lord as an internal measure of ecclesiastical efficiency. . . The ministers are, then, kinds of ecclesiastical officials—ministers of the Church rather than ministers of Christ in the Church—responsible for doing what would be in short the task of the whole body of the faithful, but which cannot be demanded of them all, because it is not possible to disturb them all from their commitments involving family life or social, economic, political or cultural activities. . . . The Church then trains, enlists and supports ‘theologians’, who are a kind of full-time laity.

(Von Allmen protests in passing against the assumption by Roman Catholics that such a view of the ministry is held by all Protestants.)

“In fact,” he adds, “if the pastoral ministry is only a full-time occupation for specialised laypeople, ordination, in the way that we traditionally practise it, is nonsense, indeed it is a contradiction and an error. For if the pastoral ministry is only that, baptism is sufficient for the valid exercise of it.” The ministry would then be merely of the bene esse of the Church, not of its esse.

Behind this view von Allmen sees the influence of the Enlightenment, the Aufklärung:

With complete disregard for the biblical doctrine of baptism, people go on affirming that from now on there is no longer any difference between the sacred and the profane; and under the shelter of this proposition, they attempt to exclude from the Church anyone who would recall this difference, and thus also the difference between the clergy and the laity.

He penetratingly adds, no doubt with those in mind who will fear the implication that the clergy are “sacred” while the laity are merely “profane”:

Theologically this difference has nothing to do with the difference between the sacred and the profane, because it concerns a distinction within the sacred; but historically it can appear to give rise to this difference, since the Enlightenment is a cultural movement manifesting itself in western Christendom which had only too great an inclination to “make sacred” the clergy and secularise the laity.

“It is”, he adds, “a ‘desecration’, a secularisation of the pastoral ministry to cease receiving it as a grace . . . to reduce it to an occupation in the internal organisation.”

Von Allmen detects two other causes for the prevalence of this inadequate view of the ministry. The first is a wrong interpretation of the royal priesthood (sacrificature) of the people of God, an interpretation which arose at the time of the Reformation as a reaction against the extreme sacerdotalism of the Middle Ages; it has, he says, been more common among Lutherans than among Calvinists, and he gets in a sly dig at some modern Roman Catholic theologians for their “Lutheran approach.” The second cause is the view that there is only one essential ministry in the Church, that of the Apostles and that, since the Apostles are no longer with us, it cannot be exercised by persons at all but only by the written testimony of the Apostles which is contained in the New Testament. His judgment on this point deserves to be quoted at length:

I do not see, either in the New Testament, or among those who were the first to read it (the Fathers of the primitive Church), or among those who re-discovered it (the Reformers), the theory which would reduce the apostolic succession to the canonisation of apostolic writings; neither in the New Testament, nor in the Fathers, nor in the Reformers, do I find the assertion that the post-apostolic ministries, the ministries in the apostolic succession, do not belong to the Lord’s institution, but to human invention; neither in the New Testament nor in the early Fathers, nor even in the Reformers, do I find the idea of a fundamental change in the Church just exactly at the death of the apostles, as if what came afterwards had no longer any actual relevance, had no longer any continuity, any genuine history, as if the Church did not have to continue, to last, without interruption, until the Parousia, and as if the pastoral ministry, the ministry in the apostolic succession, willed and instituted by Christ, was not precisely one of the graces by which he accompanies his people from one generation to another until his return. . . . And it is perhaps in this that the question of the ordination of women to the pastoral ministry is a most beneficial question: it will compel us to take up a position on the doctrine which among all of them makes us most uncomfortable, the doctrine of apostolic succession.

“But,” von Allmen continues, “it will be said . . . can one not maintain in all its truth the doctrine, at once biblical, catholic and reformed, of the pastoral ministry while at the same time ordaining women to it, since henceforth in Christ ‘there is neither male nor female’?” And this, he says, brings us to his second reason, which is both anthropological and eschatological.

Willingly accepting the text just quoted from Galatians iii, 28, he parallels it with three other Pauline texts: Romans x, 12, I Corinthians xii, 13 and Colossians iii, 11, but he remarks that all these are concerned with baptism, and he adduces six reasons why they cannot be extended to include the pastoral ministry. These merit consideration at length but I can only briefly summarise them here:

(1) It is untrue that St. Paul and the primitive Church shared the anti-feminist prejudices of their time. In many matters they showed themselves far more ready to challenge contemporary prejudices than are the Christians who criticise them today.

(2) The renewal which the Gospel brings to men and women alike does not invent, it restores: it recovers and revives what was “in the beginning.” The New Testament and Pauline doctrine about women is based not on the Fall but on Creation. “The Gospel, in other words, does not save from Creation, it saves Creation; it does not rescue from the world willed by God, it rescues the world willed by God. Redemption does not contradict Creation, it vindicates it.” To deny that there is a radical difference between man and woman in the order of redemption is to fall into Marcionism or Montanism—the precise heresies which had women priests!

(3) The polarisation of human beings into male and female “is not an accident but affects them in their very identity and in their deepest mystery.” This is why sexual sins are seen as not outside but “against” the sinner’s body. People are called to serve the Lord in their masculinity or femininity. Further, Jesus was raised as male (aner), not just as human (anthropos), II Corinthians xi, 2.

(4) St. Paul’s comparison of the nuptial union with the relation between Christ and the Church in Ephesians v is far too deeply theological for it to be possible to interchange Christ and the Church without falsifying and upsetting salvation. If the sexes were interchangeable St. Paul’s argument of the “great mystery” would become artificial and shallow.

(5) Without encouraging odious male pretensions and arrogance, there is a “gradation” in mediation: “The head of every man is Christ, and the head of the woman is the man, and the head of Christ is God” (I Corinthians xi, 3). “God reaches men by Christ, and Christ reaches women by men. Which undoubtedly implies the converse also; just as men reach God by Christ, so women reach Christ by men.” “It is no departure from this Pauline framework to say therefore that the work of God is transmitted through the mediation of Christ and, now that Christ has ascended into glory, through the derived and ministerial mediation of those whom he has charged to dispense the mysteries of God. Stated without safeguards and without qualifications, this means that between the Ascension and the Parousia, the mediator of grace among men is man rather than woman.” Von Allmen expounds this notion at length:

Expressing it in the terminology of Melanchthon, one can say that in the couple man represents the sacramental element, whereas woman represents the sacrificial element. But the sacramental element (he extends grace) is not more than the sacrificial element (she gives back grace), since these two elements are both indispensable for the work of salvation to be achieved.

Von Allmen is emphatic that “this does not in any way disqualify woman, but assigns to her her specific place.” And he makes some very suggestive final remarks:

I do not think, however, that what we are unskilfully attempting to unravel here prevents Christian woman from also becoming the mediatrix of grace. But it means that if woman assumes this place, it is either when God temporarily dispenses with man (as in the virginal conception of Jesus), or else when man withdraws from his function of principal mediator of grace, as in the case of mixed marriages in which the husband is an unbeliever and the wife consequently becomes the justifying and sanctifying element (see I Corinthians vii, 14-16). . . .

Woman could only accept and assume this place in the absence of any man or if men withdrew; then, perhaps and very exceptionally, it could be temporarily a course made tolerable by necessity. But so long as there are men in the Church, it would mean inflicting upon women a usurpation and on men a deprivation, by compelling women to forswear themselves in order to become ministers of the Word, the sacraments and discipline. For, even if they are holders of a Licence in Theology, what is a Licence in Theology in comparison with God’s creation?

(6) “The New Testament, in spite of the chance of total renewal which it provides for women as well as for men, never testifies that a woman could be, in a public and authorised way, representative of Christ.” Although there were many women who could personally fulfil the requisite conditions, Christ gave all his ministerial commissions to men, and the Church never even considered a woman as a possible successor to Judas. “This is certainly not out of disdain, or because of masculine obstinacy, but through obedience.” The events of Easter morning are normative:

It was to women that Jesus appeared first in the record of Matthew, Mark and John. They were women who were the first witnesses of the empty tomb in the record of Luke. This is fresh proof of the importance which women acquired with the Gospel and by it. But to these first witnesses of . . . what is the heart and essence of the Gospel, Jesus does not say: Go and proclaim it to the world. He gives them the command to go and tell it to the Eleven. If Jesus had wished to invest them in the Church with the apostolic ministry of the Word, the sacraments and discipline, he would have charged them to go and proclaim to the world what they had seen and heard.

Lastly, von Allmen turns to ecumenical arguments. Stressing the uniformity of the Church’s tradition against the ordination of women, he points out that the practice appears only in the nineteenth century and in circles in which the ministry itself is seen only as of the bene esse of the Church. “The Churches scandalised by such a measure understand . . . that by adopting the practice of ordaining women to the pastoral ministry, they would be doing much more than taking an internal administrative decision; they would be taking a fundamental and theological decision, which could not but have repercussions at once on the doctrine of the Church and the Ministry and on anthropology.” And, remarking that the ecumenical problem presented by the ministry is already sufficiently complicated, von Allmen concludes that “a Church which refused to allow itself to be influenced by this argument would be lacking in love and in hope and, under the safe pretext of obedience, would be making a display of pride, of insensitiveness and even of sectarian spirit.”

This concludes von Allmen’s minute and comprehensive discussion of the ordination of women to the pastoral ministry. In a much shorter appended section of his paper he discusses, with approval and enthusiasm, the development of the female ministry of the diaconate. I shall not attempt to summarise it here, partly for reasons of space and also because the details of his exposition are more relevant to the conditions of a continental Calvinist Church than to those of the Churches of the Anglican Communion. It does, however, make it plain that he is not motivated by any anti-feminist bias. Looking back on his paper as a whole I find it both refreshing and profound. In contrast with most of the discussions to which we have become accustomed in this country, his argument has several very impressive features.

The first is his determination to raise the whole question above the sub-Christian level of rights, privileges and demands, and to see it as primarily concerned with simple obedience to the decisions and commands of God.

The second is his conviction that those decisions and commands are not purely arbitrary but are coherent with human nature as God has created it.

The third is his recognition that the polarity of human nature as male and female is not a superficial or accidental differentiation, primarily concerned with the propagation of the species, but penetrates human nature to its most profound recesses.

The fourth is his insight that this polarity on the level of nature and creation has its analogue, and indeed its fulfilment, on the level of grace and redemption; mankind is bisexual by nature and bisexual too by grace.

The fifth is his detailed and exhaustive attention to the texts of the New Testament; unlike the Lambeth sub-committee, he is not content simply to throw together casually a couple of texts and then discard one of them.

Finally he provides an impressive example of the fact that opposition to the ordination of women to the priesthood is not the outcome of a crudely sacerdotal clericalism; indeed a secondary, but by no means unimportant result of his discussion, is a suggestion that a traditionally Calvinistic view of the ministry (as distinct from views characteristic of liberal Protestantism) may be much closer to that of a balanced and renewed Catholicism than one might have expected.

In the most vigorous (which does not mean the most anarchistic) Catholic circles today there has appeared a recovery of the pastoral aspect of the priesthood which does not carry with it any derogation from the sacramental and kerygmatic aspects; this is at least similar to von Allmen’s stress upon the minister’s exercise of Christ’s threefold office as prophet, priest and King. Here as in many other matters it has, I think, become clear that the real dividing line today is not between Catholicism and Protestantism in their authentic forms, but between those who believe in the fundamentally revealed and given character of the Christian religion and those who find their norms in the outlooks and assumptions of contemporary secularised culture and are concerned to assimilate the beliefs and institutions of Christianity to it.

Conclusion

It will I hope, be clear from the foregoing discussion that the extension of the ordained priesthood to women is by no means the natural and indeed inevitable development that many people today assume it to be, and that the case against it rests not upon masculine triumphalism and unreflective conservatism but upon serious theological and biblical principles. In bringing the discussion to a close I will make only two final remarks.

(1) The present epoch is one of animated and wide-ranging reconsideration of dogmatic and theological matters, and of these the nature of the Church and its ministry are not the least important. Their resolution will not be achieved overnight. It is conceivable, as a matter of pure logic, that the upshot will be a universal recognition that the priesthood is open to women as to men and that the arguments for the contrary position, such as those which have been expounded above, will have received satisfactory refutation and will be seen to be baseless. This is in my opinion unlikely and it is not in any case to be assumed in advance. In a period of theological turbulence it is not legitimate, as many appear to think, that practical effect should be given to any revolutionary proposal that may suggest itself. On the contrary such a proposal needs the most searching examination; otherwise the Church may be found to have committed itself to an irreversible course of action that future generations will condemn as reflecting the ephemeral and unsubstantial prejudices of the latter part of the twentieth century. Those who dismiss the Church’s past practice as socially conditioned and obsolete should seriously ask themselves whether their own proposals may not fall under the same condemnation. Sociology is a game at which more than one can play!

(2) Even if we leave theological considerations aside, it may well be questioned whether the contemporary world is capable of providing the Church with those guidelines for aggiornamento which it needs at the present day. Far from presenting the appearance of a social order which has discovered how to control and direct the tremendous forces which science and technology have released, it bears all the marks of a situation which has got thoroughly out of hand. The mere mention of such phrases as nuclear war, population explosion and environmental pollution is sufficient indication that the dominant influences in the world today have not yet discovered how to direct the world’s own affairs, let alone those of the Church. I am not advocating that, in order to escape contamination by the perverse and ephemeral assumptions of the present day, the Church should cling on to the perverse and outmoded assumptions of the past. What I am advocating is that the Church should be loyal, both in ordering her own life and in presenting the Gospel to the contemporary world, to the revelation which she has received from God in Christ. And with regard to the special question with which we have here been concerned, it would be naive in the extreme to suppose that the culture in which we live has been so successful in understanding the nature of sex and applying that understanding in practice as to be capable of providing the Church with principles for deciding such a matter as that of the ordination of women. On the contrary, the sexual chaos of the modern world would seem itself to show the need of such guidance as only the Christian revelation can give. No doubt it is true that in matters of sex the Church has picked up in the course of her history attitudes and assumptions that cannot be justified by Christian principles. It is all the more necessary that, having learnt the lesson, she shall explore those principles more thoroughly and not capitulate to the attitudes and assumptions of her present environment. And of no aspect of the matter is this more true than of the relation of sex to the priesthood.

Select Bibliography

The Ministry of Women. A Report by a Committee appointed by His Grace the Lord Archbishop at Canterbury. London: S.P.C.K., 1919.

Wonderful Order. By F. C. Blomfield. London: S.P.C.K., 1955.

The Ordination of Women to the Priesthood. By M. E. Thrall. London: S.C.M., 1958.

The Ministry of Women in the Early Church. By Jean Daniélou. London: Faith Press, 1961.

Concerning the Ordination of Women. (A Symposium.) World Council of Churches, 1964.

The Position of Women in Judaism. By Raphael Loewe. London: S.P.C.K. 1966.

Women and Holy Orders. The Report of a Commission appointed by the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. London: Church Information Office, 1966.

Theological Objections to the Admission of Women to Holy Orders, considered by Leonard Hodgson. London: Anglican Group for the Ordination of Women, 1967.

Women and the Ordained Ministry. Report of an Anglican-Methodist Commission on Women and Holy Orders. London: S.P.C.K., 1968.

“Women and the Priesthood.” By Alan Richardson. In Lambeth Essays on Ministry. London: S.P.C.K., 1969.

The Lambeth Conference 1968: Resolutions and Reports. London: S.P.C.K., 1968.

The Time is Now. Report of Anglican Consultative Council: Limuru, 1971. London: S.P.C.K., 1971.