AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

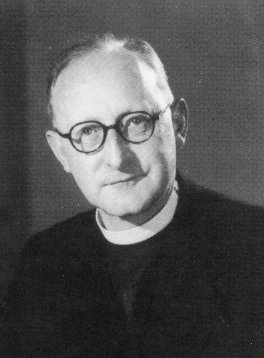

E. L. Mascall

1905-1993

Proceedings of the British Academy, 1994, 84, 409-418.

Eric Lionel Mascall 1905-1993

H. P. Owen

Eric Mascall was born on 12 December 1905 and died, at the age of eighty-seven, on 14 February 1993. The main items in his life and career are these. In his youth he showed in mathematics the intellectual brilliance he was to show later in theology. His education at Latymer Upper School was crowned by an open scholarship to Pembroke College Cambridge where he became a wrangler. After three unhappy years as a schoolmaster in Coventry he entered Ely Theological College in 1931 and was ordained in the Church of England two years later. He served in London parishes until his appointment as Sub-Warden of Lincoln Theological College in 1937. In 1945 he was made a student of Christ Church Oxford where he also became a University Lecturer in the philosophy of religion. He remained there until his election to the Chair of Historical Theology at King’s College London in 1962. After his retirement in 1973 he continued to live in the clergy house of St. Mary’s Bourne Street where he was given the title of Honorary Assistant Priest. He spent part of 1976 as a Visiting Professor in the Gregorian University at Rome. He was awarded a DD by Oxford in 1948 and by Cambridge in 1958. He was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 1974. Among the named lectures he delivered were the Bampton at Oxford and the Gifford in Edinburgh. He had been a member of the Oratory of the Good Shepherd since 1938, and on his retirement he was appointed Canon Theologian of Truro Cathedral. He travelled extensively abroad (especially in the USA, Rome, and Romania) for the purpose of meeting and addressing a variety of Anglican, Roman Catholic, and Orthodox individuals and groups. He was an only child who never married.

Although Mascall preached and lectured con-stantly, it was for his written, rather than his spoken, word that he was known. For over forty years he wrote prolifically on both philosophical and doctrinal theology. Among his major books were He Who Is (1943), Christ, the Christian and the Church (1946), Existence and Analogy (1949), the Bampton Lectures entitled Christian Theology and Natural Science (1956), Via Media (1956), Words and Images (1957), The Recovery of Unity (1958), the Gifford Lectures entitled The Openness of Being (1971), and Theology and the Gospel of Christ (1977). Mention must also be made of two books which were published in the sixties and which attacked the radical theology then current—Up and Down in Adria (a reply to the Cambridge Symposium Soundings) and The Secularisation of Christianity (an examination of the writings of Paul Van Buren and J. A. T. Robinson). Among the many articles that Mascall contributed to journals, encyclopedias, and symposia as important (and as typical) an example as any is the one on the eucharist in the first edition of the S. C. M.’s A Dictionary of Christian Theology (1969).

An assessment of Mascall’s achievements as a writer (impressive though these were) is not altogether easy. Unlike many other scholars and thinkers he is not known for one work dealing exhaustively with one topic or group of topics. His final claim to distinction rests on his reflections on many divergent topics and (no less) his critiques of many divergent authors, that are scattered throughout many works. He never brought all his leading ideas together in one book. Again, although his writings have a coherence and unity, they do not constitute a “system.” Finally, he did not invent a new terminology or offer a new interpretation of Christian beliefs.

Mascall’s achievements are, essentially, these. First, there is the scope of his writings. He dealt with all the main subjects and problems within the areas of both philosophical and doctrinal theology: the nature of God, the concept of creation, religious epistemology, the nature of religious language, the Christian doctrines of the Incarnation, the Trinity, the Church, the ministry, and the sacraments. Secondly, there is the range of his learning. This was immense. It is doubtful if any of his contemporaries was more widely read in both old and new works of both philosophical and doctrinal theology from within all the main traditions of the Church—Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and Reformed. Moreover, Mascall had a wide knowledge of the natural sciences. This is exhibited by his Bampton Lectures in which he maintained that Christian theism, so far from conflicting with the natural sciences, provided them with their best metaphysical justification. Thirdly, he consistently expounded and defended both classical theism and traditional Christian doctrines. Fourthly, he always showed a mastery of his material. He obviously understood it thoroughly and assimilated it before he began to write. Also he selected and commented on only those parts of it that were relevant to his subject or argument. Fifthly, his style was unpretentious, concise, and lucid. This entitled him to the severity with which he censured pretentiousness, wordiness, and obscurity when he found them in the writings of other theologians. Sixthly, there is the balance of his thought. This is exhibited in various ways, but especially in the relations he established between reason and revelation, the natural and the supernatural, philosophy and theology.

The third and sixth of these achievements call for comment. Thirdly, then, Mascall adhered to classical theism of the type supremely exemplified by Aquinas. God, according to such theism, is the infinite, self-existent, and immutable creator of all things. Mascall was not in the least influenced by (although he was fully conversant with) such alternatives to classical theism as Hegelianism and process thought (although these have influenced many other theologians in this century). Mascall adhered also to traditional (specifically patristic) formulations of Christian doctrines (above all those of the Trinity and the Incarnation). Christianity, for him, consisted fundamentally in the fact that the Creator, in the person of the Son, assumed our human nature for our redemption.

Lastly, there is the balance of Mascall’s thought. On the one hand he emphasised reason in the following ways. He insisted on a logically ordered and terminologically precise formulation of religious beliefs; he insisted too that these beliefs be rationally defensible; and he assigned a place to rational (or natural) theology. On the other hand he held that Christian revelation enables us to know truths concerning God that unaided reason is unable to discover. It follows that he brought together the natural and the supernatural (or, to use another, closely akin contrast, nature and grace). On the one hand he held that Christian revelation is supernatural in so far as it provides us with a knowledge and a quality of life that transcend those natural powers with which we are endowed by creation. On the other hand he held (to use language characteristic of the Thomist tradition which he found congenial and to which I shall recur) that grace presupposes nature and perfects it. Lastly, therefore, he maintained that on the one hand theology has its own subject-matter constituted by a supernatural mode of revelation, but on the other hand that philosophy is relevant to, not only natural theology, but also the construction of Christian doctrines.

Three questions may be asked concerning Mascall’s thought (as they can be asked concerning the thought of other theologians).

1. Did Mascall belong to any one “school” of Christian theology? He has often been called a Thomist or, more narrowly, neo-Thomist. John Macquarrie, in his history of twentieth-century religious thought, includes Mascall alongside Gilson, Maritain and others in his section on neo-Thomism. Certainly Mascall admired Thomas Aquinas, was widely read in him, and referred to him in his writings. Yet I do not think he was, or considered himself to be, an expert on Aquinas on a par with Gilson and other authorities on medieval thought, although it would probably be correct to say that his knowledge of Aquinas exceeded any possessed by any other Anglican theologian of his generation. Again, although his early work He Who Is was partly distinguished by the fact that in it he examined Aquinas’s thought at a time when the latter was largely neglected in this country, he tells us in his preface that he chose to call his book a study in “traditional” theism because he did not wish to tie himself too closely to Thomism. In fact He Who Is contains lengthy discussions of modern thinkers. And although in his subsequent writings he sometimes used scholastic terminology, he was on the whole more concerned with expounding Christian beliefs in non-scholastic terms and in relation to contemporary thought. Furthermore, he explicitly disagreed with those scholastics who held that Aquinas’s Five Ways prove God’s existence with logical certainty. He maintained that such a proof is unobtainable, and that belief in God must therefore rest on an apprehension or intuition of him in his created signs. On this point it is arguable that Mascall is closer to the Augustinian than to the Thomist strain in Western theology.

For the reasons I have given it is doubtful whether Mascall can be validly called a Thomist, or at least whether he can be so called without major qualifications. And he certainly did not belong to any other school of thought. His concern was not to represent any school or type of either philosophy or theology, but to expound traditional Christian beliefs through such terms (whether these were or were not scholastic ones) as he found most suitable. Therefore, in placing him within twentieth-century thought we should, first, consider him not as a Thomist, but as one who adhered to the theism typified by Aquinas, and secondly contrast him with philosophers and theologians who represented other types of thought. In adhering to classical theism Mascall differed (as I have said) from those Christian thinkers who have been influenced by other ways of understanding God and his relation to the world. In affirming that natural theology is possible and that there is an “analogy of being” (analogia entis) between God and man, Mascall differed from Barth. In affirming the objective, rational, and metaphysical nature of Christian truth Mascall differed from many existentialists.

2. Was there change or development in Mascall’s thought? There was development in the sense that he was constantly expanding or re-expressing his thought in the light of fresh reading and in the spirit of fides quaerens intellectum. Whether there was also change is another question. I have suggested one change in saying that scholastic modes of thought were less evident in his later than in his earlier books. But this is a matter of terminology. There was no change in the substance or content of his beliefs. The chief point to note here is that after taking full account of objections and opposing views he was always entirely orthodox.

3. Although Mascall united philosophy and theology, although he felt at home in both of them, and although he wrote extensively on both, the question may still be asked whether he was primarily a philosophical or a doctrinal theologian. A plausible case can be made out for saying that he was primarily a philosophical one. It has been claimed with good reason that his early philosophical works He Who Is and Existence and Analogy are those for which he will be chiefly remembered. Also in his treatment of Christian beliefs he excelled in logical analysis (not least when he was refuting those who rejected these beliefs or advocated “reductionist” interpretations of them). Therefore, although after his move to London he was concerned more with doctrinal than with philosophical theology, he found no difficulty in returning to philosophy in his Gifford Lectures in which he covered what was for him new ground by discussing “transcendental” Thomism (a late twentieth-century movement within Roman Catholicism that is essentially different from the classical Thomism derived from Aquinas).

The volume of Mascall’s published work is alone enough to make it inevitable that even those who largely agree with him should disagree on this point or that. Furthermore, even his admirers may feel that his work suffers from this or that defect. Some may wish that he had offered a more thorough treatment of Barth and Barth’s successors within Continental Protestantism; or that he had said more about the relation between Christianity and non-Christian religions; or that he had produced a summa synthesising those reflections on Christian doctrines that are dispersed throughout so many books and articles. Also, although Mascall gave grounds for rejecting extreme scepticism concerning the historicity of the gospels, it is questionable whether he always fully grasped the extent to which biblical criticism requires a reinterpretation of Christian beliefs or at least a reassessment of the evidence for them.

Nevertheless, the extent to which Mascall combined philosophical and doctrinal theology, when this is taken together with his other achievements, clearly make him an outstanding figure among British theologians in the second half of this century. This is all the more remarkable in view of the fact that his university education was in mathematics. Although he held that such an education gave a training in mental orderliness and precision, he also admitted that mathematics does not help us to solve theolo-gical problems.

No tribute to Mascall can do full justice to his writings for these reasons. Mainly, although his books have a unity and coherence constituted by the unchanging elements in his thought, each of them is self-contained and so requires a detailed review. Moreover, a large part of their usefulness consists in quotations from and discussions of other writers. However, in order to give an example of Mascall’s thought I shall consider Chapter 4 of his Words and Images. I have chosen this on the following grounds. In this book Mascall sums up, for a general as well as an academic readership, his views on religious epistemology that he examined in technical detail in his He Who Is and Existence and Analogy; this chapter shows his ability to make a telling use of quotations; it illustrates his unification of philoso-phical with doctrinal theology; and it serves as a means of developing comments I made on the description of Mascall as a Thomist.

Mascall begins by affirming that “it is essential to the position for which I am arguing that the intellect does not only reason, but also apprehends; it has as its object, not only truths but things” (p. 63). He then quotes Josef Pieper for stating this distinction in terms of the contrast between the understanding as ratio and the understanding as intellectus. He then applies this distinction to our knowledge of physical objects, other minds, and God. He maintains that in all these cases, especially the second and third, our knowledge consists in an act of intellectual intuition whereby we penetrate sensible phenomena in order to reach intelligible reality. This knowledge, so far from being “clear and distinct,” is mysterious and obscure. Moreover (at any rate so far as God is concerned) it is not obtainable without the appropriate attitudes of contemplation and humility.

Mascall then interprets our intuitive knowledge of God through the concept of mystery that he defines thus:

There are in fact three features which belong to a mystery as I am now using the term. In the first place, on being confronted with a mystery we are conscious that the small central area of which we have a relatively clear vision shades off into a vast background which is obscure and as yet impenetrated. Secondly, we find, as we attempt to penetrate this background in what I have described as an attitude of humble and wondering contem-plation, that the range and clarity of our vision progressively increase but that at the same time the background which is obscure and impenetrated is seen to be far greater than we had recognized before. It is in fact rather as if we were walking into a fog with the aid of a lamp which was steadily getting brighter; the area which we could see with some distinctness would get larger and larger but so also would the opaque and undifferentiated background in which no detail was yet visible. Thus in the contemplation of a mystery there go together in a remarkable way an increase both of knowledge and also of what we might call conscious ignorance. The third feature of a mystery to which I want to call attention is the fact that a mystery, while it remains obscure in itself, has a remarkable capacity of illuminating other things (p. 79).

At the beginning of the next paragraph Mascall continues thus:

It would be easiest to demonstrate this threefold character of mysteries and their contemplation by reference to the great revealed mysteries of the Christian faith, for example the Trinity and the Incarnation. We should see how the gradual formulation of the Church’s dogmas in more and more precise terms went hand in hand with a growing understanding of the necessarily analogical character of the terms and concepts employed and of the essentially unique and transcendent nature of the truths and realities under consideration. We should also see how the Church’s understanding of matters that were not in the narrow sense religious had been deepened as the result of light shed upon them by the Christian mysteries; how, for example, the notion of a human being as a responsible person had been enhanced by the doctrines of the tri-personality of God and of the assumption of human nature by God in the Incarnation (pp. 79-80).

It is, however, with natural (not supernatural) mysteries, and so with the apprehension of God available to all theists, that Mascall is now principally concerned. Having denied that God’s existence is rationally demonstrable, but also having assigned a place to the arguments of natural theology, Mascall affirms that belief in God must rest on an apprehension (or intuition) of him. In particular he affirms, claiming (rightly) the support of A. M. Farrer and Illtyd Trethowan, that God is intuitively known in his created effects. This is what he says on page 85: “What can thus be apprehended is neither the creature-without-God nor God-without-the creature, but the creature-deriving-being from God and God-as-the-creative-ground-of-the-creature: God-and-the-creature-in-the-cosmological relation.” Mascall then uses (as the Augustinian theologian Bonaven-tura used) the term “contuition” to signify the appre-hension of God in and with his creatures.

Any account of Mascall’s life and work would be incomplete without a reference to him as a churchman. He wrote extensively on the Church, and his whole life was dominated by a sense of belonging to it as the Body of Christ and the people of God. In particular he considered the task of the theologian to consist in a rational understanding of the super-natural revelation given to the Church. Therefore he deplored the reduction of theology to a purely academic study of its component parts from a historical point of view. Therefore too he maintained that the theologian should pursue his work with a sense of responsibility to Christian believers in general and the parish clergy in particular.

Mascall was a lifelong Anglican despite his sympathy with Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy. He has often been called an Anglo-Catholic. The description is correct in so far as if we divide members of the Anglican communion into Catholics, liberals, and evangelicals we must assign Mascall to the first of these groups. Thus he served in Anglo-Catholic parishes and held a characteristically Anglo-Catholic view of the Church’s ministry. Yet there was nothing narrow or bigoted about him. In so far as he entered into controversy with his fellow-Anglicans he did so chiefly, not along party lines, but on the grounds that they denied or at least were agnostic concerning fundamental beliefs that, being based firmly on the scriptures and the creeds, Christians of all kinds have in common. Thus in his latter days some of his strongest rebukes were administered to those Anglican theologians who undermined belief in Christ’s deity and resurrection. His capacity for ecumenical understanding was shown by the fact that in London he fitted easily into a university faculty that contained teachers of various denominations. In particular he had a high regard for his Congregationalist and Methodist colleagues in New College and Richmond College.

In the year before Mascall’s death his memoirs (entitled, enigmatically, Saraband) were published. These contain many interesting, and sometimes amusing, descriptions of men he came to know in ecclesiastical and academic contexts. From the standpoint of this obituary two facts stand out. First, although Mascall was deeply indebted to and influenced by the Anglo-Catholicism of the twenties and thirties, he was not uncritical of it and regarded its core as consisting, not in the beliefs and practices that distinguish it from other forms of Anglicanism, but in three elements that are firmly based on the New Testament—the practice of prayer, the celebration of the eucharist, and the belief that the Christian is (or can be) supernaturally transformed by his incorporation into Christ. Secondly, because Mascall’s original degrees were in science he never expected, when he was first ordained, that he would become a university teacher of theology. This is what he says at the end of his memoirs. “I have never thought of myself as an academic who found it convenient to be in holy orders but as a priest who, to his surprise, found himself called to exercise his priesthood in the academic realm” (p. 379).

Mascall’s memoirs also remind us of a fact that I have not so far mentioned and that is sometimes overlooked. Although Mascall wrote almost entirely on philosophical and doctrinal theology, he was from the beginning of his priesthood concerned with the ethical and social implications of Christianity. While he was still a curate his concern with Christian sociology was awakened by Maurice Reckitt; and he was later an active member of the Christendom group. He became a vigorous opponent of what he considered to be spiritual and moral defects of capitalism. Two of the grounds on which he was attracted to Anglo-Catholicism were its social teaching and its ministry to the urban poor.

It would be easy to obtain the impression that Mascall’s interests were wholly religious. Admittedly his main energies were devoted to reading, writing, and teaching theology. Admittedly too the account that he gives in his autobiography of his journeys abroad is almost entirely of an ecclesiastical or a religious kind. Yet he had other interests. In addition to studying the natural sciences he was well read in both classical and modern novels; he was especially fond of Haydn’s music; and he was keenly sensitive to visual beauty both in nature and in art. Moreover, although he disliked administration, and although at meetings devoted to university or college affairs he sometimes had an abstracted air that may well have concealed inner tedium, he was capable of offering shrewd judgements on the rare occasions on which he spoke.

Mascall struck many people by his gentle and unobtrusive manner, his courtesy, and his modesty. These were all seasoned and made more distinctive by his sense of humour which was expressed in his Oxford verses published as Pi in the High, and later, in London, in the verses he used to send his colleagues. In his character the amusing and the serious, the grave and the light-hearted, formed a natural unity. He had an expressive face that, according to mood and circumstance, could be either gravely set or lit up with a smile reflected in his eyes. Sometimes and to some people he could seem shy, solitary, and austere. But in the right company and situation he would open up and display the geniality for which he was no less widely known. He will be remembered in both ecclesiastical and academic circles with admiration, affection, and gratitude.