AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

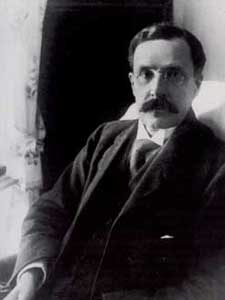

Augustus Hopkins Strong

1836-1921

From Strong’s Systematic Theology: A Compendium Designed for the Use of Theological Students, Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1976 (originally, Philadelphia: The Griffith and Rowland Press, 1701 Chestnut Street, May 1907), 52-70.

The text is taken from Volume I, Part II, Chapter I, “The Existence of God.” I have excised the many long paragraphs of bibliographical reference that follow the expository paragraphs, for it is to Strong's line of exposition that I wish to draw attention:

. . . the knowledge of God’s existence . . . is presupposed in all other knowledge as its logical condition and foundation.

This is “homegrown” presuppositionalism about twenty years before Cornelius Van Til and sixty before Greg Bahnsen.

Anthony Flood

September 12, 2009

The whole text of Systematic Theology is now online.

Anthony Flood

August 30, 2011

Origin of Our Idea of God’s Existence

Augustus Hopkins Strong, D.D., LL.D.

Introduction

God is the infinite and perfect Spirit in whom all things have their source, support, and end.

The existence of God is a first truth; in other words, the knowledge of God’s existence is a rational intuition. Logically, it precedes and conditions all observation and reasoning. Chronologically, only reflection upon the phenomena of nature and of mind occasions its rise in consciousness.

I. First Truths in General

1. Their nature.

A. Negatively—A first truth is not (a) Truth written prior to consciousness upon the substance of a soul—for such passive knowledge implies a materialistic view of the soul; (b) Actual knowledge of which the soul finds itself in possession at birth—for it cannot be proved that the soul has such knowledge; (c) An idea, undeveloped at birth, but which has the power of self-development apart from observation and experience—for this is contrary to all we know of the laws of mental growth.

B. Positively—A first truth is a knowledge which, though developed upon occasion of observation and reflection, is not derived from observation and reflection—a knowledge on the contrary which has such logical priority that it must be assumed or supposed in order to make any observation or reflection possible. Such truths are not, therefore, recognized first in order of time; some of them are assented to somewhat late in the mind’s growth; by the great majority of men they are never consciously formulated at all. Yet they constitute the necessary assumptions upon which all other knowledge rests, and the mind has not only the inborn capacity to evolve them so soon as the proper occasions are presented, but the recognition of them is inevitable so soon as the mind begins to give accounts to itself of its own knowledge.

2. Their criteria.The criteria by which first truths are to be tested are three:

A. Their universality. By this we mean, not that all men assent to them or understand them when propounded in scientific form, but that all men manifest a practical belief in them by their language, actions, and expectations.

B. Their necessity. By this we mean, not that it is impossible to deny these truths, but that the mind is compelled by its very constitution to recognize them upon the occurrence of the proper conditions, and to employ them in its arguments to prove their non-existence.

C. Their logical independence and priority. By this we mean that these truths can be resolved into no others, and proved by no others; that they are presupposed in the acquisition of all other knowledge and can therefore be derived from no other source than an original cognitive power of the mind.

II. The Existence of God a First Truth

1. That the knowledge of God’s existence answers the first criterion of universality is evident from the following considerations:

A. It is an acknowledged fact that the vast majority of men have actually recognized the existence of a spiritual being or beings, upon whom they conceived themselves to be dependent.

B. Those races and nations which have at first seemed destitute of such knowledge have uniformly, upon further investigation, been found to possess it, so that no tribe of men with which we have thorough acquaintance can be said to be without an object of worship. We may presume that further knowledge will show this to be true of all.

C. This conclusion is corroborated by the fact that those individuals, in heathen or Christian lands, who profess themselves to be without any knowledge of a spiritual power or powers above them do yet indirectly manifest the existence of such an idea in their minds and its positive influence over them.

D. This agreement among individuals and nations so widely separated in time and place can be most satisfactorily explained by supposing that it has its ground, not in accidental circumstances, but in the nature of man as man. The diverse and imperfectly developed ideas of the supreme Being which prevail among men are best accounted for as misinterpretations and perversions of an intuitive conviction common to all.

2. That the knowledge of God’s existence answers to the second criterion of necessity will be seen by considering:

A. That men, under circumstances fitted to call forth this knowledge, cannot avoid recognizing the existence of God. In contemplating finite existence, there is inevitably suggested the idea of an infinite Being as its correlative. Upon occasion of the mind’s perceiving its own finiteness, dependence, responsibility, it immediately and necessarily perceives the existence of an infinite and unconditioned Being upon whom it is dependent and to whom it is responsible.

B. That men, in virtue of their humanity, have a capacity for religion. This recognized capacity for religion is proof that the idea of God is a necessary one. If the mind upon proper occasion did not evolve this idea, there would be nothing in man to which religion could appeal.

C. That he who denies God’s existence must tacitly assume that existence in his very argument by employing logical processes whose validity rests upon the fact of God’s existence. The full proof of this belongs under the next head.

3. That the knowledge of God’s existence answers the third criterion of logical independence and priority may be shown as follows:

A. It is presupposed in all other knowledge as its logical condition and foundation. The validity of the simplest mental acts, such as sense-perception, self-consciousness, and memory, depends upon the assumption that a God exists who has so constituted our minds that they give us knowledge of things as they are.

B. The more complex processes of the mind, such as induction and deduction, can be relied only by presupposing a thinking Deity who has made the various parts of the universe and the various aspects of truth to correspond to each other and to the investigating faculties of man.

C. Our primitive belief in final cause, or, in other words, our conviction that all things have their ends, that design pervades the universe, involves a belief in God’s existence. In assuming that there is a universe, that the universe is a rational whole, a system of thought-relations, we assume the existence of an absolute Thinker, of whose thought the universe is an expression.

D. Our primitive belief in moral obligation, or, in other words, our conviction that right has universal authority, involves the belief in God’s existence. In assuming that the universe is a moral whole, we assume the existence of an absolute Will, of whose righteousness the universe is an expression.

To repeat these four points in another form—the intuition of an Absolute Reason is (a) the necessary presupposition of all other knowledge, so that we cannot know anything else to exist except by assuming first of all that God exists; (b) the necessary basis of all logical thought, so that we cannot put confidence in any one of our reasoning processes except by taking for granted that a thinking Deity has constructed our minds with reference to the universe and to truth; (c) the necessary implication of our primitive belief in design, so that we can assume all things to exist for a purpose, only by making the prior assumption that a purposing God exists—can regard the universe as a thought, only by postulating the existence of an absolute Thinker; and (d) the necessary foundation of our conviction of moral obligation, so that we can believe in the universal authority of right, only by assuming that there exists a God of righteousness who reveals his will both in the individual conscience and in the moral universe at large. We cannot prove that God is; but we can show that, in order to [explain?] the existence of any knowledge, thought, reason, conscience, in man, man must assume that God is.

III. Other Supposed Sources of Our Idea of God’s Existence

Our proof that the idea of God’s existence is a rational intuition will not be complete until we show that attempts to account in other ways for the origin of the idea are insufficient, and require as their presupposition the very intuition which they would supplant or reduce to a secondary place. We claim that it cannot be derived from any other source than an original cognitive power of the mind.

1. Not from external revelation, whether communicated through (a) the Scriptures or (b) through tradition; for, unless man had from another source a previous knowledge of the existence of God from whom such a revelation might come, the revelation itself could have no authority for him.

2. Not from experience, whether this mean (a) the sense-perception and reflection of the individual (Locke), (b) the accumulated results of the sensations and associations of past generations of the race (Herbert Spencer), or (c) the actual contact of our sensitive nature with God, the supersensible reality, through the religious feeling (Newman Smyth).

The first form of this theory is inconsistent with the fact that the idea of God is not the idea of a sensible or material object, nor a combination of such ideas. Since the spiritual and infinite are direct opposites of the material and finite, no experience of the latter can account for our idea of the former.

The second form of the theory is open to the objection that they very first experience of the first man, equally with man’s latest experience, presupposes this intuition, as well as the other intuitions, and therefore cannot be the cause of it. Moreover, even though this theory of its origin were correct, it would still be impossible to think of the object of the intuition as not existing, and the intuition would still represent to us the highest measure of certitude at present attainable by man. If the evolution of ideas is toward truth instead of falsehood, it is the part of wisdom to act upon the hypothesis that our primitive belief is veracious.

The third form of the theory seems to make God a sensuous object, to reverse the proper order of knowing and feeling, to ignore the fact that in all feeling there is at least some knowledge of an object, and to forget that the validity of this very feeling can be maintained only by previously assuming the existence of a rational Deity.

3. Not from reasoning, because

(a) The actual rise of this knowledge in the great majority of minds is not the result of any conscious process of reasoning. On the other hand, upon occurrence of the proper conditions, it flashes upon the soul with the quickness and force of an immediate revelation.

(b) The strength of men’s faith in God’s existence is not proportioned to the strength of the reasoning faculty. On the other hand, men of greatest logical power are often inveterate skeptics, while men of unwavering faith are found among those who cannot even understand the arguments for God’s existence.

(c) There is more in this knowledge than reasoning could ever have furnished. Men do not limit their belief in God to the just conclusions of argument. The arguments for the divine existence, valuable as they are for purposes to be shown hereafter, are not sufficient by themselves to warrant our conviction that there exists an infinite and absolute Being. It will appear upon examination that the a priori argument is capable of proving only an abstract and ideal proposition, but can never conduct us to the existence of a real Being. It will appear that the a posteriori arguments, from merely finite existence, can never demonstrate the existence of the infinite. In the words of Sir Wm. Hamilton (Discussions, 23—“A demonstration of the absolute from the relative is logical absurd, as in such a syllogism we must collect in the conclusion what is not distributed in the premises”—in short, from finite premises we cannot draw an infinite conclusion.

(d) Neither do men arrive at the knowledge of God’s existence by inference; for inference is condensed syllogism, and, as a form of reasoning, is equally open to the objection just mentioned. We have seen, moreover, that all logical processes are based upon the assumption of God’s existence. Evidently that which is presupposed in all reasoning cannot itself be proved by reasoning.

IV. Contents of This Intuition

1. In this fundamental knowledge that God is, it is necessarily implied that to some extent men know what God is, namely, (a) a Reason in which their mental processes are grounded; (b) a Power above them upon which they are dependent; (c) a Perfection which imposes law upon their moral natures; (d) a Personality which they may recognize in prayer and worship.

In maintaining that we have a rational intuition of God, we by no means imply that a presentative intuition of God is impossible. Such a presentative intuition was perhaps characteristic of unfallen man; it does belong at times to the Christian; it will be the blessing of heaven (Mat. 5:8—“The pure in heart . . . shall see God”; Rev. 22:4—“they shall see his face”). Men’s experiences of face-to-face apprehension of God, in danger and guilt give some reason to believe that a presentative knowledge of God is the normal condition of humanity. But, as this presentative knowledge of God is not in our present state universal, we here claim only that all men have a rational intuition of God.

It is to be remembered, however, that the loss of love to God has greatly obscured even this rational intuition, so that the revelation of nature and the Scriptures is needed to awaken, confirm, and enlarge it, and the special work of the Spirit of Christ to make it the knowledge of friendship and communion. Thus from knowing about God, we come to know God (John 17:3—“This is life eternal, that they should know thee”; 2 Tim. 1:12—“I know him whom I have believed”).

2. The Scriptures, therefore, do not attempt to prove the existence of God, but, on the other hand, both assume and declare that the knowledge that God is, is universal (Rom. 1:19-21, 28, 2; 2:15). God has inlaid the evidence of this fundamental truth in the very nature of man, so that nowhere is he without a witness. The preacher may confidently follow the example of Scripture by assuming it. But he must also explicitly declare it, as the Scripture does. “For the invisible things of him since the creation of the world are clearly seen” (καθοραται–spiritually viewed); the organ given for this purpose is the νους (νοουμενα); but then—and this forms the transition to our next division of the subject—they are “perceived through the things that are made” (τοις ποιήμασι Rom. 1:20).