AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

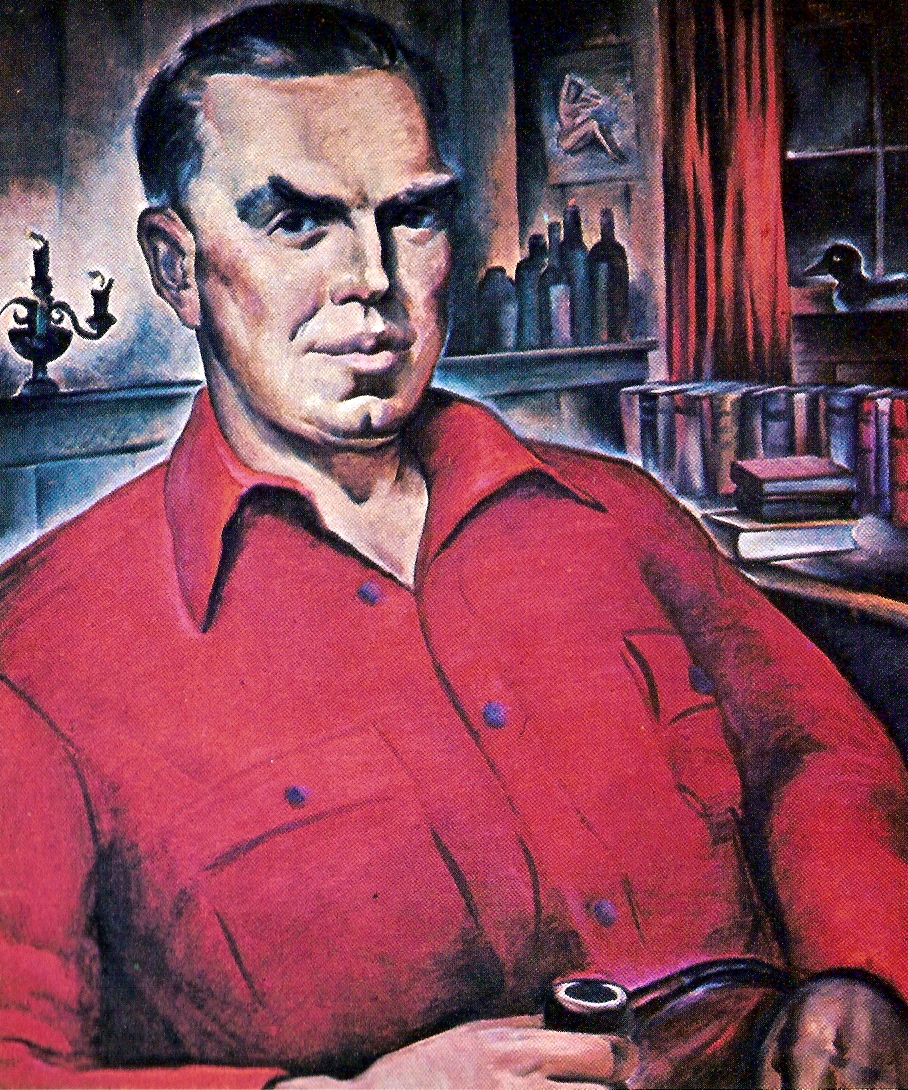

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Pearl Harbor after a Quarter of a Century

Harry Elmer Barnes

X: The Final Question

“

Whether our entry into the second World War was for the good of America and the world will be debated for a long time, and how it is settled should depend on the ultimate verdict as to whether the world and the United States did benefit from our entry.”

—Harry Elmer Barnes

We may well close the discussion of Pearl Harbor with reference to some basic considerations that relate to the historiography of the subject. The critics of the revisionist historians dealing with Pearl Harbor have violently criticized the latter for placing the responsibility for the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor overwhelmingly on Roosevelt. They reveal thereby a strange lapse of logic. Actually, Roosevelt’s success in producing a surprise attack was an immensely, even uniquely, adroit achievement in piloting an overwhelmingly pacifically-inclined country into the most extensive and destructive war of history without any threat to our safety through aggressive action from abroad.

These selfsame anti-revisionist critics, who so heatedly denounce Revisionists for revealing and underlining Roosevelt’s responsibility, are the very ones who also vehemently contend that, as a fundamental moral imperative, we simply had to enter the second World War to preserve our national self-respect and promote the safety and preserve the civilized operations of the human race. Hence, Roosevelt’s success in putting us into this war should appear to them to be greatly to his credit as a statesman—”a good officer,” as Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. has described him in this connection. Elementary logic would make it seem clear that the anti-revisionist writers should be grateful to Revisionists for having demonstrated Roosevelt’s responsibility for this great and benign achievement far more definitively and clearly than the anti-revisionists have ever done. By denying his responsibility for what is to interventionists a superlative act of humanitarian statesmanship the anti-revisionists are depriving him of the credit due him for his allegedly comprehensive services to mankind.

Two historians, Professor Thomas A. Bailey of Leland Stanford University and Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. of Harvard, were very early logical in this matter. They admitted decades back that Roosevelt lied us into war, but contend that he did so for the good of our country, which was not wise enough to know what was for its best interests at the time. At the Republican convention of 1944, Clare Boothe Luce called attention to Roosevelt’s lying the United States into war, but with a somewhat more cynical and sardonic leitmotif. A complete and frank treatment of the matter is provided by T. R. Fehrenbach in his F. D. R.’s Undeclared War (1967).

If political deception was required to save the human race in 1941, then it was fortunate that Roosevelt was at the helm in the White House at this moment and a superb virtuoso in public mendacity (the “credibility gap”) was thus directing the destiny of mankind. An eminent American general, and a personal friend of mine, sent me this reminiscence:

The day that F. D. R. died, I drove General MacArthur home. We talked of those who had disappeared from the scene since the war started, especially of F. D. R. As MacArthur got out of the car, he turned to me and said: “Well, the Old Man has gone; a man who never told the truth when a lie would suffice!”

It may be conceded that MacArthur’s appraisal of Roosevelt’s veracity is possibly a bit exaggerated, but it is certainly an understatement to observe that the material presented in this article makes it clear that the “credibility gap” in the White House did not begin with Lyndon Johnson and his Vietnam War. Moreover, those who believe that it was indispensable for the welfare of humanity for the United States to enter World War II, should not speak too unkindly of the “credibility gap.” According to their own assumptions, it was the sole means of saving the human race from September, 1939, to December, 1941. At least one interventionist historian has possessed the logic and honesty to agree with my contentions. Writing in the Chicago Tribune of December 20, 1967, Professor John H. Collins of Northern Illinois University, summarizes the situation more competently than any other statement that I have read:

Prof. Harry Elmer Barnes . . . has produced a detailed account of the events leading up to Pearl Harbor (as reported in The Tribune Dec, 7), using documents generally unknown to the public. And what does it all come to?

That Roosevelt, while hypocritically pretending to desire peace, was actually provoking, or rather plotting, a Japanese attack, and that Roosevelt was driving for war against the Axis from 1939 on, and never meant his “again and again” statement of the campaign of 1940.

I say Barnes is bringing a microscope to show us an elephant. If there were naive souls in 1940 who did not know that Roosevelt was for war, and was pulling every wire known to political manipulation to get war, their simplicity cannot now be set right by any documentary proof.

As to Pearl Harbor, it was what Roosevelt had been hoping for. If he was very pious, it was what he had been praying for. If there had been any incantation that could have summoned it up out of a witches’ caldron, he would have been boiling newts’ heads and snakes’ eyes in the White House kitchen.

But wherefore all the moral indignation? It was Roosevelt’s highest duty to get the United States into the war by whatever means would achieve that result. Because the American people were so stupid, ignorant, and complacent as to believe in ignoble ease and complacent sloth, Roosevelt was compelled to lie, bamboozle, and scheme behind a facade of pacifism.

He had the courage to disregard morality to save the country, and his Machiavellian policy should be given its proper meed of historical praise.

Whether our entry into the second World War was for the good of America and the world will be debated for a long time, and how it is settled should depend on the ultimate verdict as to whether the world and the United States did benefit from our entry. The opposing viewpoints are still as sharply drawn and vigorously stated today as at the time of Pearl Harbor. In an article in the New York Times of August 21, 1966, Professor A. J. P. Taylor, the popular British historian, contended that:

There was, in my opinion, one statesman of superlative gifts and vision between the wars. This was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who is likely to appear to posterity as the greatest man of his age.

The opposing view was set forth vividly and with more factual support in a private letter to me by Henry Beston, one of the most learned and cultivated American scholars, literary critics, and publicists of this century:

Roosevelt was probably the most destructive man who ever lived. He left the civilized West in ruins, the entire East a chaos of bullets and murder, and our own nation facing for the first time an enemy whose attack may be mortal. And, to crown the summit of such fatal iniquity, he left us a world that can no longer be put together in terms of any moral principle.

As a realistic appraisal of the second World War, I know of nothing better than the following comments of the distinguished journalist, author and critic, Malcolm Muggeridge, in Esquire, February, 1968:

In all the immense literature about the 1939-1945 war, one may observe a legend in process of being shaped. Gradually, authentic memories of the war—of its boredom, its futility, the sense it gave of being part of a process of inevitable decomposition—fade in favor of the legendary version, embodied in Churchill’s rhetoric and all the other narratives by field marshals, air marshals and admirals, creating the same impression of a titanic and forever memorable struggle in defense of civilization. In fact, of course, the war’s ostensible aims—the defense of a defunct Empire, a spent Revolution, and bogus Freedoms—were meaningless in the context of the times. They will probably rate in the end no more than a footnote on the last page of the last chapter of the story of our civilization.