AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

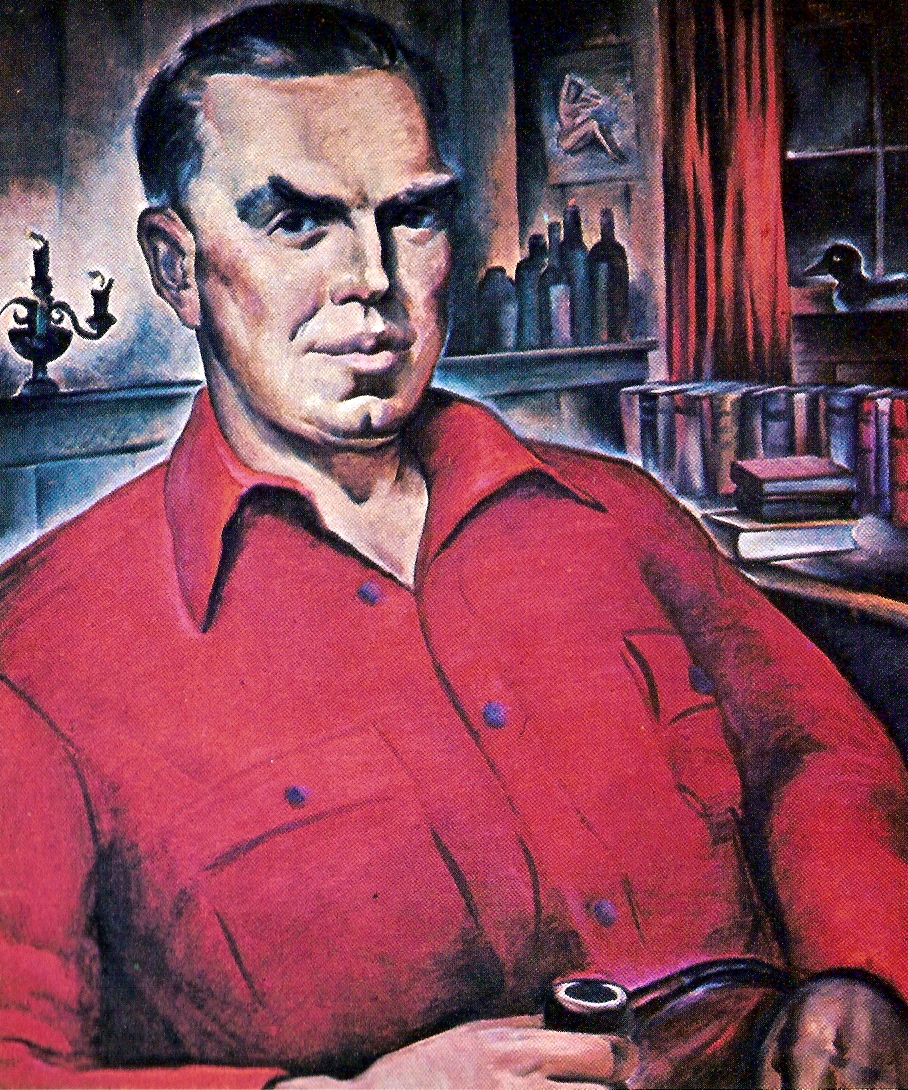

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Pearl Harbor after a Quarter of a Century

Harry Elmer Barnes

Eulogizing his friend in an editorial (posted elsewhere on this site), Murray Rothbard wrote:

“. . . Left and Right is privileged to present what tragically turned out to be Harry Barnes’ last work . . .: the true story of Pearl Harbor. . . . We have been delighted and honored that Harry chose the pages of Left and Right to present what he proposed to be his final word on the subject, the culminating synthesis of a quarter century of revisionist inquiry.”

And more than six years after the “new Pearl Harbor,” no less accompanied by a bodyguard of lies than was the old, we are happy to help give this masterwork of revisionism a wider reading on the 40th anniversary of its publication as well as of the passing of its inspiring author. Its continuing relevance should be obvious.

Anthony Flood

Posted March 28, 2008

From Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought, IV, 1968, 9-132. We have merely formatted (and, where necessary, corrected) the text that The Memory Hole provides here. Every issue of Left and Right may be read in facsimile on Mises.org, including this essay.

Table of Contents

I: The Lessons of Pearl Harbor More Relevant Than Ever Before [Scroll down]

II: Roosevelt’s Policies Prior to Pearl Harbor

III: Washington Should Not Have Been Surprised When The Japanese Attacked Pearl Harbor

IV: Keeping Short and Kimmel in Ignorance of a Surprise Japanese Attack

V: The So-Called Warnings to Short and Kimmel

VI: The Blackout of Hawaii on the Eve of Pearl Harbor

VII: The Overall Responsibility of Roosevelt for the Surprise Attack

VIII: How We Entered War with Japan Four Days before Pearl Harbor

“As the military episode that brought the United States into the second World War, the results of Pearl Harbor already indicate that this produced drastic and possibly ominous changes in the pattern of American relations to the rest of the world. We voluntarily and arbitrarily assumed unprecedented burdens in feeding and financing a world badly disrupted by war. The international policy of George Washington and the 'fathers' of the United States, based on non-intervention but not embracing isolation, was terminated for any predictable period.

President Truman continued the doctrine of the interventionist liberals of the latter part of the 1930’s, to the effect that the United States must be prepared to do battle with foreign countries whose basic ideology does not conform with that of the United States. . . . The United States sought to police the world and extend the rule of law on a planetary basis, which actually meant imposing the ideology of our eastern seaboard Establishment throughout the world, by force, if necessary, as in Vietnam. By the twenty-fifth anniversary of Pearl Harbor, the United States was being informed by both official policy and influential editorials that we must get adjusted to the fact that we face permanent war . . . .”

—Harry Elmer Barnes

I: The Lessons of Pearl Harbor More Relevant Than Ever Before

The surprise Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, is regarded by most persons who recall it at all as an isolated dramatic episode, now consigned to political and military archeology. Quite to the contrary, on account of our entry into the war, it became one of the most decisive battles in the history of the human race. It has already proved far more so than any of the “fifteen decisive battles” immortalized by Sir Edward Creasy.

The complex and cumulative aftermath of Pearl Harbor has played the dominant role in producing the menacing military pattern and political impasse of our time, and the military-industrial-political Establishment that controls this country and has sought to determine world policy. It created the four most likely focal points for the outbreak of a thermonuclear war which may lead to the extermination of the human race—Berlin, Formosa, Southeast Asia and the Middle East—unless future sudden flare-ups like that in Cuba in 1962 may turn the lethal trick. Hence, while Creasy’s battles may have decided the fate of important political entities and alignments in the past, Pearl Harbor may well have deeply affected the fate of mankind. American entry into the war produced atomic and nuclear warfare as well as Russian domination of Central Europe and the triumph of Communist China in Asia.

Moreover, a detailed study of how Pearl Harbor came about provides ominous lessons as to the uncertainties of human judgment and the eccentricities in personal conduct that control the outbreak of wars, an ever more crucial consideration in determining the destinies of the human race as we move on in the nuclear era. The damage done to our Pacific Fleet, although its significance was exaggerated at the time, was impressive and devastating. But it was a trivial matter compared to the fact that the Japanese attack put the United States actively into the second World War. The personal and political ambitions, professional stereotypes, public deceit and mendacity (the credibility gap), ruts and grooves of thinking and action, and the martial passions that brought on Pearl Harbor would, if repeated in such a crisis as that raised by the Cuban incident of 1962, or a future one in Berlin, Formosa, Vietnam, or the Middle East might very well destroy civilization.

As the military episode that brought the United States into the second World War, the results of Pearl Harbor already indicate that this produced drastic and possibly ominous changes in the pattern of American relations to the rest of the world. We voluntarily and arbitrarily assumed unprecedented burdens in feeding and financing a world badly disrupted by war. The international policy of George Washington and the “fathers” of the United States, based on non-intervention but not embracing isolation, was terminated for any predictable period.

President Truman continued the doctrine of the interventionist liberals of the latter part of the 1930’s, to the effect that the United States must be prepared to do battle with foreign countries whose basic ideology does not conform with that of the United States. He further elected to create and perpetuate a cold war until actual hot warfare breaks out, as it did in Korea in 1950 and in southeast Asia a decade later. The United States sought to police the world and extend the rule of law on a planetary basis, which actually meant imposing the ideology of our eastern seaboard Establishment throughout the world, by force, if necessary, as in Vietnam. By the twenty-fifth anniversary of Pearl Harbor, the United States was being informed by both official policy and influential editorials that we must get adjusted to the fact that we face permanent war, an especially alarming outlook in a nuclear era in which the two major powers are already amply prepared to “overkill” their enemies. “Perpetual war for perpetual peace” has become the American formula in relation to world affairs.

Drastic changes in the domestic realm can also be attributed to the impact of our entry into the second World War. The old rural society that had dominated humanity for millennia was already disintegrating rapidly as the result of urbanization and technological advances, but the latter failed to supply adequate new institutions and agencies to control and direct an urban civilization. This situation faced the American public before 1941 but the momentous transformation was given intensified rapidity and scope as a result of the extensive dislocations produced by years of warfare and recovery. These gave rise to increasing economic problems, temporarily fended off by a military-industrial-political complex that provided no permanent solution. The social problems of an urban age were enlarged and intensified, crime increased and took on new forms that became ever more difficult to combat, juvenile disorganization became rampant, racial problems increased beyond precedent, and the difficulties of dealing with this unprecedented and complicated mass of domestic issues were both parried and intensified by giving primary but evasive consideration to foreign affairs in our national policy and operations. Hence, a discussion of the lessons of Pearl Harbor for today reveals a situation which is more than a matter of idle curiosity for military antiquarians.

Moreover, as will be pointed out during our treatment of the Pearl Harbor problem, we had by 1941 entered into a system of diplomatic secrecy and international intrigue and deception which had already committed this country to world war several days before the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor, and without the slightest knowledge of this on the part of the American public. The implications of such a contingency in a nuclear age are as obvious as they are astounding and ominous.

Despite the crucial importance of the Pearl Harbor story for American citizens, it is certainly true that, although the twenty-seventh anniversary of the surprise Japanese attack has now arrived, only a small fraction of the American people are any better acquainted with the realities of the responsibility for the attack than they were when President Roosevelt delivered his “Day of Infamy” oration on December 8, 1941. The legends and rhetoric of that day still dominate the American mind. Interestingly enough, the American people narrowly missed having an opportunity to learn the essential truths about Pearl Harbor in a sensational and fully publicized manner less than three years after the event. As a result of research by his staff, and possibly some “leaks” from Intelligence officers of 1941, Thomas E. Dewey, the Republican candidate for the presidency, had learned during the campaign of 1944 that President Roosevelt had been reading the intercepted Japanese diplomatic messages in the Purple and other codes and was aware of the threat of a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor at any time after November 26, 1941, but had failed to warn the commanders there, General Walter C. Short and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, in time to avert the attack or to meet it effectively. Dewey considered presenting these vital facts in a major campaign speech.

Roosevelt learned of this through the Democratic grapevine planted at Republican headquarters and, in understandable alarm, pressured Mr. Dewey through General George C. Marshall to abandon his plan, on the ground that it would endanger the war effort by revealing that we had broken Japanese codes. Marshall twice sent Colonel Carter W. Clarke to urge Dewey not to refer to Pearl Harbor during the campaign. To cover up for Roosevelt, Marshall has contended that he operated on his own initiative in sending Clarke to importune Dewey. As Clarke knew by this time, the basis of his plea was spurious, namely, that such a speech by Dewey would first reveal to the Japanese that we had broken their Purple diplomatic code. Actually, the Japanese had learned of this from the Germans by the end of April, 1941, over three years before the 1944 campaign. Dewey did not know this at the time and, as a supposedly patriotic duty, he suppressed the speech and the publicity which might have won the election for him.

In a column written for the King Features Syndicate and widely published on the eve of the 1964 election, the famed journalist, John Chamberlain, described Dewey’s lugubrious retrospective observations on his deception by Roosevelt and Marshall in 1944:

Nixon’s 1960 agony recalls that of Thomas Dewey in 1944, when the Republicans knew practically all the details about the surprise at Pearl Harbor yet were loath to put the issue into the campaign lest they reveal to the Japanese that the United States had broken a critical code.

This columnist vividly recalls riding in a car from Elmira to Geneva, New York, in August of 1945 with Dewey and listening to his rueful account of the decision to say nothing about Pearl Harbor. The worst of it, from Dewey’s standpoint, is that he had a suspicion that the Japanese had changed their codes long before 1944, which would have made campaign revelations about Pearl Harbor harmless to the U. S. from a military standpoint.

When I talked to Tom Dewey in 1945, he thought he might have been cheated out of a winning issue in 1944.

Chamberlain made similar revelations in an article in Life while the Congressional Pearl Harbor investigation was still in progress, yet Mr. Dewey was never called to testify. John T. Flynn gave me much more detail about Pearl Harbor and the Dewey campaign by personal correspondence and conversation in the autumn and early winter of 1944. Flynn had been active at Republican headquarters during the campaign.

My suggestion to Mr. Dewey in 1966 that he publicize the facts of the 1944 situation in connection with the twenty-fifth anniversary of Pearl Harbor proved fruitless. This is entirely understandable. In 1966, Mr. Dewey was not a candidate for the presidency. He was the responsible head of a great legal firm, and publicity so damaging to Roosevelt’s public reputation might have alienated important clients not only among Democrats but also Republicans who were interventionist-minded relative to World War II. It might, however, also have done more to give the American public some idea of the realities of Pearl Harbor than the combined writings of revisionist historians in a whole generation since 1944.

An intriguing and not fully resolved point stems from the fact that the Japanese learned from the Germans at the end of April, 1941, that the United States had broken their Purple code in which they sent top secret diplomatic messages. Why, then, did they continue to use the code? Some authorities believe that, despite the reliability of their informants, the top level Japanese officials could not bring themselves to believe that their code had actually been cracked, and that this vanity was abetted by the officials who had been responsible and wished to cover up the leak. Other authorities assert that the Japanese went ahead with the Purple code because they did not care if we did read it, since reading it would make it all the more clear to the American officials that Japanese peace efforts were sincere and that the Japanese would go to war if the peace negotiations should fail. This explanation, which I find more convincing, is also confirmed by Tojo’s repeated deadlines set for the end of negotiations during November, 1941.

During the nearly quarter of a century since 1944, and despite a series of official investigations, the defenders of Roosevelt among historians, journalists and politicians have been able to keep the vital information about the responsibility for war with Japan and the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor from the American people. In this article the attempt will be made to set forth as much of this withheld information as can be put down within the space available.