AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

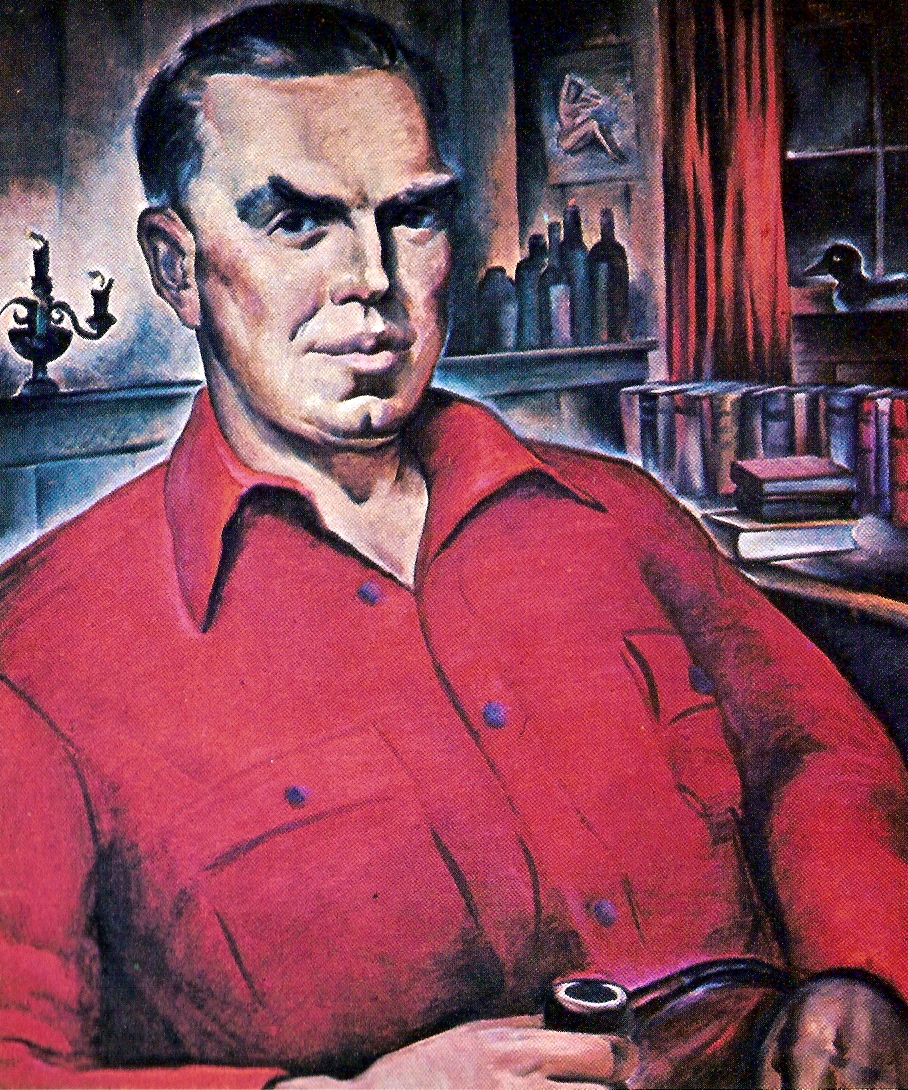

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Pearl Harbor after a Quarter of a Century

Harry Elmer Barnes

VII: The Overall Responsibility of Roosevelt for the Surprise Attack

“

[General George C.] Marshall’s directed behavior from December 4 to 7, 1941 . . . was one of the most masterly products of Roosevelt’s genius for deception but was directly opposed to Marshall’s personal views about starting war at this time. Indeed, it is certainly high time that revisionist scholars should cease placing the main blame for compelling [General] Short and [Admiral] Kimmel to remain unwarned on foreign collaborators or on Roosevelt’s American agents or stooges, like Hull, Marshall, Stark and Turner, and put it squarely where it belongs, on the source of their directions and operations: Roosevelt himself.

—Harry Elmer Barnes

The essential facts and details explaining why and how Pearl Harbor was surprised on Sunday, December 7, 1941, have now been presented. There remains the question of the responsibility for the overall trends and developments which led to the attack itself. Here, I believe that fundamental responsibility can also be overwhelmingly—almost solely—attributed to Roosevelt and his policies, in which there was far more deliberation than inadvertence.

Our entering the second World War was mainly the product of a political program: Roosevelt’s turning to armament and war to bail himself out of the difficulties created by the failure of his domestic program. The surprise attack was a political rather than a military scandal. It may, of course, be open to argument as to whether Roosevelt’s New Deal was not ideologically and morally superior to the program and methods of his conservative political opponents at home and that the latter must share the responsibility for his shift to armament and war because of their stupid hostility and often malicious resistance to domestic reforms.

Secretary of State Hull has been vigorously criticized for his arrogant and pharisaical diplomacy, based on unrealistic platitudes, beatitudes, and banalities, and designed to make it impossible to arrive at a fair and decent understanding with Japan over Far Eastern problems. But for all this Roosevelt was primarily responsible. He had no hesitation whatever in being his own Secretary of State when Hull’s policies did not coincide with his own, even to the extent of insulting Hull by relying heavily on Raymond Moley, Stimson and Henry Morgenthau in such matters. Roosevelt permitted Hull to carry on diplomatic relations with Japan in the manner which he did because Hull’s policies, strongly influenced by his principal advisor on Far Eastern matters, the Japanophobe scholar, Stanley K. Hornbeck, agreed perfectly with Roosevelt’s program. There has rarely been a greater meeting of minds between a president and his secretary of state than in the accord between Roosevelt and Hull over our negotiations with Japan in 1941. If Hull had entertained contrary views Roosevelt would no more have hesitated to push Hull aside over Japan than he did in the case of the Morgenthau Plan dealt with at the Quebec Conference in September, 1944.

So far as the economic background of Pearl Harbor is concerned, the responsibility was almost solely that of Roosevelt, whether we consider the effort to save and prolong his political career by creating a military economy to replace the New Deal or his use of economic and financial methods to produce the economic strangulation of Japan and force her into war. In the latter, he was vigorously opposed, at least when instituted, by the top army and navy officials. Even Admiral Turner strongly criticized this move.

Roosevelt’s militant program was thoroughly in accord with his personal attitudes and aims. His hostility to Japan went back to a deep-seated boyhood affection for China and antipathy to Japan that were closely related to his China-oriented family financial history, and to the alleged bad impression of the traits, behavior and political ambitions of the Japanese people made on him by a “Japanese schoolboy,” who was a fellow student with Roosevelt at Harvard. Months before he was inaugurated, he had a long conference on January 9, 1933, with Stimson, the most eminent and passionate Japanophobe among the prominent American statesmen of the present century. They were brought together by Roosevelt’s close adviser, Felix Frankfurter, who had been a subordinate of Stimson in Frankfurter’s early legal career. Stimson’s hatred of Japan and his erratic ideas about “aggressor nations” appealed to Roosevelt, and these became the basis of the latter’s Japanese policy from January 9, 1933, when he met Stimson, to the attack on Pearl Harbor. When Raymond Moley and Rexford G. Tugwell vigorously urged Roosevelt not to accept Stimson’s bellicose attitude toward Japan, he answered that he could not very well help doing so in the light of very satisfactory personal and financial relations that his maternal grandfather had enjoyed with China.

Roosevelt’s first striking gesture in revealing his aggressive foreign policy, the Quarantine formula enunciated in the Chicago Bridge speech of October 5, 1937, was straight Stimson political and diplomatic ideology, and Stimson almost immediately released an approving statement. It would be unfair, however, to attribute to Stimson full responsibility for Roosevelt’s hostile behavior toward Japan. He did not have to accept Stimson’s position, and he did so only because it was in full agreement with his own personal attitude and public policy. Late in 1937, as noted earlier, Roosevelt sent the very able American naval officer, Captain Royal E. Ingersoll, to London, and in January, 1938, Ingersoll discussed the possible relations and operations of the United States and Great Britain in case they “were involved in a war with Japan in the Pacific which would include the Dutch, the Chinese, and possibly, the Russians.” From this time onward Ingersoll had no doubt that Roosevelt had war with Japan in the back of his mind and made no bones of this fact in his confidential discussions with his professional associates.

In the summer of 1941, when Roosevelt felt ready really to put the screws on Japan, he logically summoned Stimson, already made Secretary of War, to come forth and actively implement the Stimson doctrine, while Hull proceeded with his evasive and procrastinating diplomatic homilies. When Roosevelt allowed or directed Hull to kick over the modus vivendi on November 26th, he did this in direct opposition to the policy of Marshall and Stark, who wished more time to get ready for war with Japan.

Roosevelt has been criticized by some on the ground that he got entangled with Churchill, and that the latter dragged him into war. There is no doubt of the powerful but unneeded efforts of Churchill in pressing Roosevelt towards military action, but Roosevelt opened the door for British importuning when he sent Ingersoll to Europe in the winter of 1937-38, asked for an opportunity to collaborate in September, 1939, and later agreed with and cooperated in the Anglo-American joint effort against Germany. The over two years of voluminous secret communications between Roosevelt and Churchill, which determined the course of relations between the United States and Britain, completely hidden from the American public, were instituted at Roosevelt’s request.

Marshall’s directed behavior from December 4 to 7, 1941, which so cleverly and successfully helped us into war by assuring the launching of a successful Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, was one of the most masterly products of Roosevelt’s genius for deception but was directly opposed to Marshall’s personal views about starting war at this time. Indeed, it is certainly high time that revisionist scholars should cease placing the main blame for compelling Short and Kimmel to remain unwarned on foreign collaborators or on Roosevelt’s American agents or stooges, like Hull, Marshall, Stark and Turner, and put it squarely where it belongs, on the source of their directions and operations: Roosevelt himself.

Anti-revisionist partisans of Roosevelt will pounce upon the above conclusions as a striking example of the “devil theory of history.” Even if it were, which I do not concede, it is fully as valid as their own “saint theory of history”: the portrayal of Roosevelt as “Saint Franklin”! They utilize the latter unhesitatingly and almost invariably in defending Roosevelt against all charges of duplicity and responsibility in producing war with Japan and in bringing about the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. They proclaim him a superb statesman and a major benefactor of all mankind through his encouraging the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 and bringing the United States into the war as soon as he was able to do so in the face of the strongly anti-interventionist public opinion in the United States right down to Pearl Harbor. This “saint theory” in regard to Roosevelt has been valiantly, even aggressively in some cases, upheld by writers like Admiral Samuel E. Morison, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Thomas A. Bailey, Herbert Feis, Samuel Flagg Bemis, Roberta Wohlstetter and T. R. Fehrenbach; indeed, by virtually every opponent of the revisionist approach to 1939 and 1941. Revisionist historians can logically insist that, if the anti-revisionist writers wish to attack the “devil theory” mote in the eyes of revisionist scholars, the “saint theory” devotees must remove this saintly beam from their own eyes.

More important, however, is the fact that the indictment of Roosevelt as overwhelmingly responsible for war with Japan and the surprise at Pearl Harbor is in no sense any literal application of the devil theory of history. We are here concerned only with the rejection of peaceful overtures from Japan long preceding Pearl Harbor and American responsibility for a successful surprise attack there on December 7, 1941. For these deeds and actions Roosevelt was primarily and personally responsible. There is no pretense here of dealing thoroughly with the causes of wars in general, the responsibility for the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, the reasons why Roosevelt turned from peace to armament and war after the campaign of 1936, the basis of Roosevelt’s desire for the glamour of being a war president, the wisdom of his domestic opponents in opposing the New Deal system, and the like.

Even less is there any attempt here to present and analyze the basic geographical, biological, economic, sociological and psychological causes of wars in general, which account for the genesis of all modern wars including the second World War. Neither the devil nor the saint theory is any explanation of such fundamental considerations. Nobody under-stands this fact better than I do. Whatever defects my writings on Revisionism and diplomatic history may have, it is beyond reasonable dispute that I have given more attention to the fundamental causes of wars in my writings than any professional diplomatic historian who has ever dealt with the subject. Not even the case of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the second World War can induce me to abandon this basic approach to wars.