AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

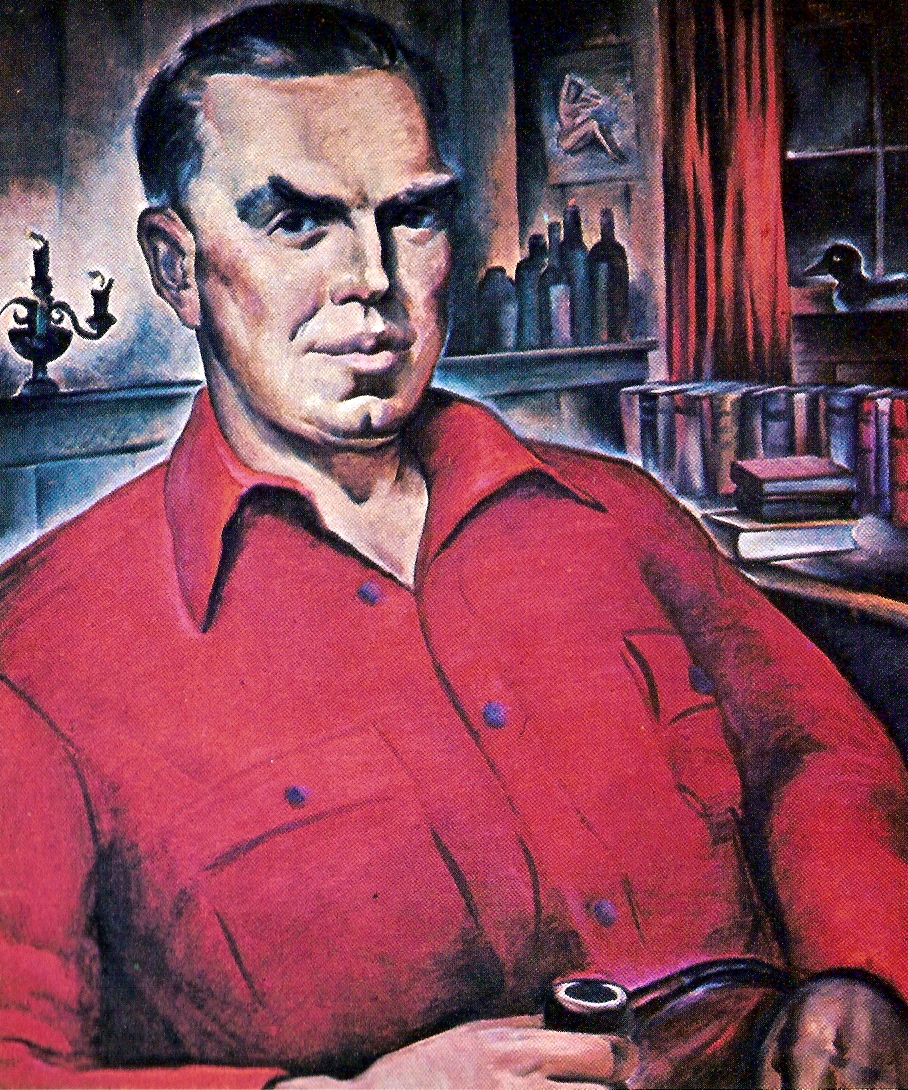

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Pearl Harbor after a Quarter of a Century

Harry Elmer Barnes

VIII: How We Entered War with Japan Four Days before Pearl Harbor

“. . . Roosevelt had approved an agreement that the United States would go to war to protect the interests and territory of allies in the Antipodes, thousands of miles from the United States, without even the semblance of an attack on the United States by Japan. . . .

The ABCD agreement and Rainbow 5 hung like a sword of Damocles over Roosevelt’s head. It exposed him to the most dangerous dilemma of his political career: to start a war without an attack on the American forces or territory . . . .

He apparently . . . had felt confident that Hitler would give him a valid pretext for war on the Atlantic. But when Hitler had failed to provide a suitable provocative act it became apparent that the United States must enter the war through the back door of Japan.”

—Harry Elmer Barnes

Our naval losses at Pearl Harbor that resulted from the surprise attack there have become a major item in American and world history primarily because it is almost universally believed that it was the Japanese attack that brought the United States into war with Japan. Actually, the United States had been put into war with Japan by the action of the Dutch authorities at Batavia, approved by the Dutch government, on December 3rd, Washington time, four days before the Japanese struck at Pearl Harbor.

Roosevelt remarked, when, about 9:30 P.M. on December 6th, he read the first thirteen parts of the Japanese reply to Hull’s ultimatum of November 26th, that “This means war.” He had known by the forenoon of the 6th, if not two days earlier, that we were already involved in war with Japan. How this had come about requires a brief review of the plans, arrangements and agreements whereby the United States could be involved in war without any attack by Japan upon American territory, forces or flag, a situation which was a repudiation of Roosevelt’s promises to the American people and of the Democratic platform of 1940. They were the ultimate development and implementation of Captain Ingersoll’s visit to Europe in the winter of 1937-38.

Unneutral American acts even prior to Roosevelt’s election in 1940 on the platform of avoiding war had furnished Germany with a legitimate basis for making war on the United States. Such were the Destroyer Deal of September, 1940, and the allotting of large quantities of arms and ammunition to the British. Immediately following the election of 1940, plans to involve us in war with Japan got under way in real earnest, in case the Axis Powers should not rise to the bait afforded by “Lend Lease” and convoying on the Atlantic. These have been mentioned earlier but may be reviewed here.

Anglo-American joint-staff conferences in Washington held from January through March, 1941, drew up general plans for cooperation in war against the European Axis Powers and also envisaged a containing war with Japan. They were known as the ABC-1 plans (land and sea) and ABC-2 (air). In April, another conference was held in Singapore, and the Dutch were brought in more directly through ABD. While still regarding Germany as the main immediate enemy, provisions were also made for joint action against Japan if the latter proceeded beyond the line 100° East and 10° North or 6° North and the Davao-Waigeo line, or menaced British or Dutch possessions in the southwest Pacific or independent countries in that area. This agreement between the United States, the British and the Dutch was known as ADB. Together, the agreements were known as ABCD. Stimson and Knox approved the ABC-1 plan for the United States to make it look good for the record. Although approving them verbally, Roosevelt did not officially sponsor these agreements in writing and they did not call for congressional approval. Marshall and Stark balked at ADB and its inclusion in ABCD because it introduced political considerations in a military program, but they had to play along with Roosevelt and did so to the very end in early December, 1941.

When the joint-staff conferences were over, the American military services drew up specific war plans to implement these staff agreements ending in ABCD. The joint Army and Navy basic war plan was known as Rainbow 5, also usually called WPL 46 in relation to naval operation in the Pacific. The subsidiary part that related to the operations of the Pacific fleet under Admiral Kimmel was known as WPPac 46. It was developed to implement the basic war plan and to coordinate the Pacific fleet operations with the provisions of Rainbow 5 (WPL 46).

Roosevelt apparently had indicated to Marshall and Stark that he intended to place the basic war plans before Congress prior to their being implemented, but whether he so intended or not, he had failed to do so when his hand was called on December 5th and 6th. The essence of the matter is that Roosevelt had approved an agreement that the United States would go to war to protect the interests and territory of allies in the Antipodes, thousands of miles from the United States, without even the semblance of an attack on the United States by Japan. On the heels of these ABCD agreements and the derived war plans, Admiral Stark, when promulgating Rainbow 5 (WPL 46), sent word to his admirals in leading outposts that the question of war was no longer a matter of whether, but of when and where. Marshall distributed Rainbow 5 to his field commanders, and Roosevelt unofficially approved it in May and June.

The ABCD agreement and Rainbow 5 hung like a sword of Damocles over Roosevelt’s head. It exposed him to the most dangerous dilemma of his political career: to start a war without an attack on the American forces or territory, or refusing to follow up the implementation of ABCD and Rainbow 5 by Britain or the Dutch. The latter would lead to serious controversy and quarrels among the prospective allies, with the disgruntled powers leaking Roosevelt’s complicity in the plan and exposing his mendacity.

He apparently took this risk rather lightly until July, 1941, because he had felt confident that Hitler would give him a valid pretext for war on the Atlantic. But when Hitler had failed to provide a suitable provocative act it became apparent that the United States must enter the war through the back door of Japan. When the latter had been consigned to economic strangulation in July 1941, when the back door plan had apparently been definitely implemented at the Argentia meeting, and when the peace efforts of Konoye had been rejected, this agreement to start a war on Japan without an attack on American forces or territory became a pressing and serious political problem for Roosevelt if he wished to have a united country behind him to support his war effort. It became increasingly so when the Japanese began to send extensive convoys of troops and equipment into the southwest Pacific in November. These convoys might pass the magic line specified by the ABCD agreement, and the Dutch, British and Australians might call his hand by invoking the American promise to act jointly against the Japanese as envisaged in ABCD and Rainbow 5 (WPL 46). The matter of getting a suitable Japanese attack somewhere now became the most vital of all Roosevelt’s political problems. There would no longer be any serious difficulty in inciting Japan to accept war, but Japan had to commit the “first overt act” and it had to be against the United States.

There was always the probability that the Japanese would attack Pearl Harbor because this action had been implicit in Pacific naval strategy for years, but a Japanese task-force attack at Hawaii involved a long ocean voyage and there was always a possibility that it might be intercepted en route. It was this consideration, as well as the fact that this belated plan might also save the fleet at Pearl Harbor, which led Roosevelt to turn to his “three small vessels” stratagem on December 1st, to which reference has already been made several times.

Roosevelt appears to have obtained his inspiration to set up this scheme through reports of the menacing attitude and behavior of Japanese naval ships toward two American Yangtse River gunboats, the Luzon and Oahu, as they approached and passed Formosa on a voyage from Shanghai to Manila on November 29th and 30th (Washington time). Hitherto, the Japanese had not paid any serious attention to routine American ship movements off the coast of Asia But on the 29th and 30th, they all but fired on the gunboats Luzon and Oahu.

On December 1st, immediately after his return from Warm Springs, Roosevelt summoned Admiral Stark and instructed him to order Admiral Hart, commander of the Asiatic fleet stationed at Manila, to select, equip and man three “small vessels” which could move out into the path of the Japanese task forces going southward and draw fire from Japanese planes or ships, thus giving Roosevelt his all-important and indispensable attack, and one that was on an American ship. The ostensible purpose of equipping and sending out the three “small vessels,” as explained by Stark to Hart, was to have them carry out reconnaissance operations relative to Japanese ship movements and to reports—to act as a “defensive information patrol.”

Admiral Hart, as also did Stark, recognized from the outset that any such operation for these little ships was palpably “phony.” Hart was carrying out the needed reconnaissance and reporting the results to Washington. For this he had suitable vessels and planes, while for such a role the use of the three “small vessels” was nothing short of fantastic. To retain Hart’s respect, Stark had made it clear that the whole conception of equipping and dispatching the three “small vessels” for reconnaissance was Roosevelt’s and not his, a fact which Mrs. Wohlstetter characteristically conceals in her treatment of the three “small vessels” episode.

Only two of the “small vessels” had been made ready to sail out into the path of the Japanese convoys and invite attack before the Japanese struck at Pearl Harbor. To get this baiting stratagem under way promptly, Roosevelt had Stark suggest to Hart that he might use the converted yacht Isabel, which had been made over into the dispatch boat of the Asiatic fleet and the Japanese had been acquainted with its identity for some time. Hart realized that on this assignment the Isabel was to be bait for a Japanese attack, which displeased him since the vessel was very useful to the fleet. Yet he did not wish to seem to be defying the President’s wishes. He sensibly solved his dilemma by sending the Isabel out as directed but under instructions which rendered it as unlikely as possible to be attacked and sunk by the Japanese. These instructions were directly contrary to Roosevelt’s plans and intentions, and Hart knew they were. The Isabel was not even repainted before being dispatched, which assured that the Japanese would be able to recognize it, and the sailing orders given by Hart were such as to make it appear very unlikely to the Japanese that it was a provocative “man-o-war.”

These precautions may well have saved the Isabel from attack, the Japanese recognized it and were not stupid or rash enough to fire on it. Although out on its mission for some five days, only one Japanese plane even buzzed the Isabel. Despite his protective directions Hart had feared that the Isabel would be sunk, and he told the commander when he returned that he had never expected to see him alive again after his departure. If the Isabel episode had been handled in the manner that Roosevelt wished and provided the maximum provocation to trigger-happy Japanese pilots or gunners there might not have been any attack on Pearl Harbor and the fleet there could have been saved.

The second “small vessel,” the little schooner Lanikai, which was commanded by Lieutenant (now Admiral) Kemp Tolley, although equipped with a cannon and machine gun to bait the Japanese into thinking it was a warship, had only a dilapidated radio unfit either to receive or transmit messages. If Tolley had seen the whole Japanese fleet assembled in front of him he could not have sent back any report. Although Tolley at once reported its useless condition, there was no attempt to replace his radio equipment and provide him with suitable instruments to report his observations. The Lanikai was awaiting dawn on December 7th to leave the entrance to Manila Bay and expose itself to Japanese gunfire when news came of the attack on Pearl Harbor and the “small vessel” turned back. The combination of the utter lack of usable radio equipment and the haste shown in trying to get the Lanikai manned and sent out in the path of Japanese planes and ships provides the best evidence of the real purpose of the “three small vessels” scheme. The third “small vessel” had not even been selected because of lack of time, but there is no reason to believe that it would have been superior in nature or equipment to the Lanikai.

Roosevelt’s timing of the three “small vessels” stratagem was, as noted earlier, much too belated to work out as he had hoped. The order to equip and dispatch them should have been issued at least as early as Hull’s ultimatum of November 26th. As a result of Hart’s sensible evasion of Roosevelt’s wishes, the Isabel sought to avert a Japanese attack. The Lanikai was not able to put to sea effectively to challenge Japanese fire before the attack on Pearl Harbor on the 7th, and, as will be shown shortly, the United States had been already involved in war with Japan without any attack on this country through the Dutch implementation of the ABCD agreement and Rainbow 5 (Rainbow A-2 for the Dutch) on December 3rd, Washington time. Roosevelt gave the order concerning the three “small vessels” as soon as the idea occurred to him, but he appears to have forgotten the Panay incident of 1937 and he could not have known of the menacing Japanese behavior toward the Luzon and Oahu before the afternoon or evening of November 30th. Hence, he could not have sent out the order to equip and dispatch the “three small vessels” before he did on the forenoon of December 1st as soon as he returned from Warm Springs. The brilliant and ingenious inspiration came too late.

That the United States was involved in war with Japan by 10:40 A.M. on the morning of December 6th because of the British invocation of ABCD and Rainbow 5 has been shown in detail by Charles A. Beard in his book President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War 1941 and by George Morgenstern in his chapter (6) in Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace. But there was authentic evidence presented during the post-war Pearl Harbor investigations that this country was actually involved in war with Japan by December 3rd, Washington time, when the Dutch at Batavia, with the approval of the home government, invoked the ABCD agreement and Rainbow 5 (A-2) because Japanese forces had passed the line 100 East and 10 North and was thought to be threatening the Dutch possessions as well as the Kra Peninsula and Thailand. The Dutch reported that the Japanese might arrive within sixty hours.

This astonishing information was revealed in the so-called Merle-Smith message sent out of Melbourne, Australia, on the morning of December 5, 1941 (December 4th, Washington time) to Generals MacArthur and Short. It is remarkable that even most American revisionist historians have missed its full significance. The essential facts about the message were noted by George Morgenstern in his Pearl Harbor, published in 1947 and the first comprehensive book on the subject, and some six years later by Percy L. Greaves on pages 430-431 of Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace. But Morgenstern and Greaves failed to follow through because they accepted as valid the official statement by Washington that the Merle-Smith message did not reach Washington until 7:58 on the evening of December 7th, several hours after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

The full import of the Merle-Smith message was first revealed by Commander Hiles in the spring of 1967, and it was precisely mentioned and briefly described a little later by Ladislas Farago in his book The Broken Seal (Chapter 26) but Farago, who learned the significance of the message from Hiles, did not develop its full significance.

Colonel Van S. Merle-Smith was the American military attache in Melbourne, Australia, in December, 1941, and his aide was Lieutenant Robert H. O’Dell. Most of our information about this Merle-Smith message comes from the testimony of O’Dell before the Clarke Inquiry and the Army Pearl Harbor Board in 1944, especially the testimony before Colonel Carter W. Clarke, who allowed O’Dell to testify in straightforward fashion. Merle-Smith had died in the interval between 1941 and 1944.

About 5:00 P.M. on Thursday, December 4th, Australian time (Wednesday, December 3rd, Washington time), Merle-Smith and O’Dell were invited to a conference at which were present Air Chief Marshal Charles Burnett, commander of the Australian air force, and Commander Saom, the Dutch liaison officer from Batavia.

Burnett told Merle-Smith that he had received information from Vice-Admiral C. E. L. Helfrich, commander-in-chief of the Dutch Navy in the East Indies, that Japanese naval forces had crossed the magic line of 100 East and 10 North and were threatening the Dutch or American possessions. Commander Saom then informed Burnett, for the special benefit of Merle-Smith, that the Dutch authorities in Batavia had ordered the execution of ABCD, and Rainbow 5 (A-2), the Dutch phase of Rainbow 5, which was to be invoked only in the case of war. He further told Burnett and Merle-Smith that the order to execute Rainbow 5 (A-2) had already gone into effect and that the Dutch counted on the assistance of the American Navy. Burnett then brought the conference to a close because he had to attend an Australian War Council meeting that evening.

When Merle-Smith returned to his office, he discussed this sensational information with Captain Charles A. Coursey, the American naval attache at Melbourne, but the latter apparently declined to send any warning to naval authorities in cooperation with Merle-Smith. If he sent one to Hart, Kimmel or Stark it must have been suppressed and destroyed later on. Merle-Smith remained determined to alert MacArthur and Short. Hence, he drafted an identical message to each of them, and ordered O’Dell to code it, which was done. At Burnett’s request by telephone that evening the message was held up until the forenoon of December 5th, Australian time (December 4th, Washington time.) It was sent to MacArthur and Short by fast cablegram about 11:00 A.M. the morning of the 5th, Australian time (4th for Washington). Short was requested to decode and read it and then transmit it to Washington. The message should have reached Manila and Fort Shafter on the early afternoon of the fifth (the 4th at Washington), and Short could have been able to forward the message to Washington before evening.

The evidence indicates that the message was not decoded by Short at Fort Shafter, possibly due to lack of trained personnel or proper code keys, but was sent on to Washington, where it was suppressed for at least two, and possibly three, days. It could have reached the Army Signal Corps in Washington during the evening or night of December 4th, Washington time, since it was sent from Melbourne to Hawaii at about 11:00 A.M. on December 5th, Australian time, or December 4th, Washington time. According to the official Signal Corps report in Washington, however, the Merle-Smith message was not received in Washington until 7:59 P.M. on December 7th.

Commander Hiles has cogently pointed out that this alleged late arrival of the Merle-Smith cable in Washington is most probably a fraudulent evasion: “We are not dealing here with intercepts of Japanese messages but with regular service communications whereby such functions normally proceed promptly and in an orderly fashion. Encoded messages from military attaches in time of crisis such as this one do not lie around neglected unless for ulterior purposes of no honest portent or through gross negligence.”

At any rate, nothing in the Merle-Smith message was sent back to Short after being decoded and read by the Signal Corps in Washington. Had it been sent back to Short in full immediately after it should have been received and processed, it could have produced a full alert at Hawaii on the early morning of the 5th, Washington time. It certainly could have been sent back to Short in time to produce an alert during the 5th, Washington time, and averted the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. When O’Dell was called to testify before the Army Pearl Harbor Board, the government only presented a paraphrase of the original Merle-Smith message which arbitrarily changed some of the dates and modified the content in other places. For instance, it represented the defensive action of the Dutch and Australian planes as starting at 8:00 A.M. on the 7th, when this actually took place on December 5th, Australian time, or December 4th Washington time. Even the original copy of the Merle-Smith message in the Clarke Inquiry exhibits bears a phony date for the transmission of the message from Melbourne, giving it as December 6th when it should have been the 5th, Australian time, or the 4th Washington time.

The crucial and decisive news about the ominous movement of a Japanese convoy beyond the magic line established by the ABCD agreement and Rainbow 5 (Rainbow Plan A-2 to the Dutch in this instance) and the defensive action of the Australian and Dutch planes, which had been confided to Merle-Smith on the afternoon of the 4th and morning of the 5th, Australian time (3rd and 4th Washington time), definitely meant that Holland, Great Britain and the United States were now committed to war with Japan. The Far Eastern situation was in full conformity with the ABCD agreement and Rainbow 5 (A-2), as confirmed by the American “War Cabinet,” made up of Roosevelt, Stimson, Hull, Knox, Marshall and Stark, at noon on November 28th.

The United States, Britain and the Dutch were already discussing the critical situation created by the obligations under ABD, ABCD and Rainbow 5 (A-2) and the southward movement of Japanese forces even before the Merle-Smith message could have reached Washington. At 5:30 P. M. on December 4th, Admiral Stark was advising London that the Dutch warning of the possibility of a Japanese attack against the Philippines and the Netherland East Indies could not be ruled out, and went on to say: “If Dutch authorities consider some warning should be given Japan CNO [Stark] believes that it should take the form of a declaration to Japan that in view of the current situation Japanese naval vessels or expeditionary forces crossing the Davao-Waigeo line would be considered hostile and would be attacked. Communicate these views to the Admiralty and Dutch Naval Command in London.” In discussing this statement with Hull, Stark indicated that he had shown it to Roosevelt and the latter had approved it. If Washington had been directly and independently informed of the Australian-Dutch action on the afternoon of December 3rd or the 4th (Washington time) before the Merle-Smith message could have arrived there is no record of it.

The next move to activate the understanding and actions related to ABCD and Rainbow 5 came on the early evening of the 5th when Lord Halifax, the British ambassador in Washington, called on Secretary Hull at his apartment in the Carlton Hotel, and informed Hull, who had already been well primed by Stark’s message to London on the 4th, that the British Foreign Office believed that the time had now come for the immediate cooperation of the British and Americans with the Dutch in defending the Far East against the Japanese movements in the southwest Pacific according to the ABCD agreement and Rainbow 5. Hull may have told Halifax that Stark’s message to London, and also informing the Dutch, on the afternoon of the 4th, approved by Roosevelt, indicated that the latter agreed with Halifax. At any rate, Hull expressed his “appreciation” of Halifax’s call and information, and Halifax left, apparently content. At least, he informed London that the United States would back up the implementation of the ABCD agreement and Rainbow 5 (A-2) by the Dutch and Australians with armed support.

London sent this critically important information to Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, commander of the British forces in the Far East, with headquarters in Singapore. Brooke-Popham forthwith informed Captain John H. Creighton, the American naval observer in Singapore, about the definitive message he had received from London that the United States was approving the Anglo-Dutch implementation of ABCD. Creighton immediately sent the information to Admiral Hart at Manila.

On December 6th, two messages from the American ambassador in London, John G. Winant, were received in Washington and were immediately put into the hands of Roosevelt and Hull. The first reached Roosevelt and Hull at 10:40 A.M.; and the second at 3:05 P.M. The first called attention to the Japanese violation of the magic line in the Far East and to the threat to the Dutch and British possessions and independent countries in the Southwest Pacific. The second gave further information about the menacing Japanese movements and stated that Britain was hard-pressed for time in getting information from the United States that was needed to be able to guarantee the protection of Thailand, which the Dutch had reported on December 3rd might by reached by the Japanese in sixty hours.

These two messages confirmed the information given by Halifax to Hull on the evening of the 5th to the effect that Britain regarded the situation in the Far East as activating the ABCD agreement for Anglo-American-Dutch cooperation in the Far East to repel Japan in that region. The conditions required for cooperation and war according to ABCD and Rainbow 5, and the decision of the Washington War Cabinet on November 28th had all been met by the Japanese movements.

The crucial agreement that war against Japan had now begun in the Far East was made in an all-important top secret conference at the White House on the afternoon of the 6th at which Roosevelt, Hull, Halifax and Robert G. Casey, the Australian Minister in Washington, were present. Halifax was apparently satisfied that Roosevelt was backing up Hull’s response of the previous evening, for he at once informed the British Foreign Office to that effect. Indeed, there had never been any valid reason for imagining that Roosevelt would repudiate his agreements under ABCD and Rainbow 5, as much as he may have regretted having to enter a war before he had an attack on either one of the three “small vessels” or on Pearl Harbor. As was usual in such vital situations, Roosevelt kept no notes or official record of this crucially significant conference on the afternoon of the 6th.

Roosevelt had given Halifax and Casey this confirmation without in any way informing or consulting Congress. Although he approved the Anglo-Dutch-Australian implementation of ABCD and Rainbow 5 that involved war in the Far East with full American participation, he informed Casey that he would postpone public announcement of this fact until Tuesday, December 9th, when he would officially warn Japan. Doubtless, this decision to delay was based on the hope that in the interval between Saturday and Tuesday he would get the desperately desired news of an attack on either one of the three “small vessels” or on Pearl Harbor. He would have preferred the former but he got the latter.

The first definite information given to an American representative in the Far East that Roosevelt had confirmed the participation of the United States in the war that was now under way after having been initiated by the Dutch implementation of ABCD and Rainbow 5 (A-2) on Wednesday, December 3rd, Washington time, came in the precise and conclusive statement of Air Marshal Brooke-Popham to Captain Creighton at Singapore to which reference has already been made. This contained London’s confirmation that Roosevelt had approved the Dutch and British implementation of Rainbow 5. Captain Creighton sent this information to Admiral Hart from Singapore on December 6th, at which time Hart was being visited by Vice-Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, who had just been placed in command of all British naval forces in China. Hart showed the Creighton message to Phillips, who immediately departed to return to Singapore. As he left Hart’s office, the latter told him that he would send the American destroyers then based on Borneo to aid Phillips and the British naval forces, thus confirming the agreement that the United States was at war in the Far East.

The importance of the Creighton statement, in establishing the case against Roosevelt in regard to the violation of his “sacred” promises to “American fathers and mothers” and his repudiation of the Democratic platform of 1940 by abandoning his assurance that this country would not enter war without an attack on American forces, is emphasized by the desperate effort made during the Joint Congressional Committee Investigation of Pearl Harbor in 1945-46 to blot out the validity, if not the very existence, of Creighton’s crucial statement that he sent to Hart.

By this time Admiral Hart had retired from military service and was a U.S. Senator from Connecticut. When Senator Ferguson pressed him about the Brooke-Popham message before the JCC, he “passed the buck” and refused to discuss it, stating that Creighton, who was to follow him on the witness-stand, was the best qualified person to know the facts. Creighton was not present but he heard about Hart’s statement, contacted Hart, and told him that he had no knowledge whatever that any such message as that from Brooke-Popham and allegedly forwarded by him to Hart had ever existed. Hart informed Creighton that he had the latter’s own copy with him in a locked case and directed that Creighton should come at once to get it for his testimony the next day. Creighton did so and had it in his possession when he appeared the next day before the Joint Congressional Committee. He was compelled to produce it and admitted that it must be authentic because it bore his code signature and was signed in Singapore. When, even then, Creighton persisted in maintaining that he could not recall ever having sent such a message and, if he did, his statements therein were only a matter of hearsay, Senator Barkley, chairman of the JCC, came to Creighton’s rescue and by devious rhetoric was able to dismiss this critically important message as nothing more than a rumor. It was emasculated and buried despite Ferguson’s efforts, which were really not up to par on this occasion. Senator Brewster might have done much better.

There were a number of disillusioning collapses of integrity on the part of witnesses during the post-Pearl Harbor investigations but probably no other was as pathetic as that of Creighton. His behavior on the stand has been exposed and castigated by Beard and Morgenstern, although they and other fair-minded students of the affair have recognized the tremendous pressure that seems to have been exerted on Creighton to falsify his testimony, which may have been even greater and more intimidating than was evident on the surface at the time when he was testifying before the JCC. This had happened with other witnesses whose testimony departed impressively from the facts with which they were acquainted.

A friend of mine, who was very familiar with military Magic and messages and the post-Pearl Harbor investigations and was a personal friend of Creighton, has informed me that the latter was, at the time of his testimony before the JCC, already sadly afflicted with a serious tropical disease contracted at Singapore that had virtually ruined his memory. His health failed steadily and he died prematurely. Hence, it is possible that Creighton actually could not remember the message he had sent to Hart. In that case, his condition should have been recognized and he should not have been subjected to the ordeal of testifying. If this is not the explanation, then he was either obviously intimidated or was consciously trying to put on a show to muddle up the Brooke-Popham episode. Fortunately, it does not really matter for other corroborative evidence we now have enables us to complete the picture and the patterns.

While we are discussing testimony, it may be well to call attention to the nature of O’Dell’s testimony before the Clarke Inquiry and the Army Pearl Harbor Board. O’Dell knew he was in on a big secret, had heard of the Pearl Harbor investigations, and wanted to get his story into the record. He had stirred up too much curiosity safely to be ignored. As it turned out, it would have been better for the Roosevelt record to have ignored him. The Clarke Inquiry had been designed solely to deal with the question of military Magic for General Marshall, and O’Dell was the only witness that Clarke called who did not have some relation with Magic, of which O’Dell knew nothing. But he could not prudently be ignored any longer and apparently Clarke thought he would let O’Dell testify and then leave his story to be buried in the record.

It is quite evident that Clarke and Gibson, his assistant, were nonplussed when O’Dell got started and poured forth like an opened floodgate, letting more cats out of the bag than any other witness in any of the post-Pearl Harbor investigations. He was one of the few witnesses who did not have to be prompted or have information wormed out of him; he could not get it out fast enough. It was vital information, spontaneously offered and with no punches pulled, and his testimony was dynamite for the defenders of the Administration. This is emphatically proved by the bogus three-day delay alleged by Washington in “receiving” the Merle-Smith message. Although it could have reached Washington by the evening of the 4th, Washington time, and must have arrived by the 5th, it has been represented as arriving at 7:58 P.M. on the 7th, hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

When the Army Pearl Harbor Board examined O’Dell later on the same day, they treated him far more cautiously, and produced only the partly falsified paraphrase of the Merle-Smith message and sought unsuccessfully to confuse O’Dell. The Joint Congressional Committee very carefully kept O’Dell from testifying at all, even in the light of the vital material he had revealed before Clarke and the APHB.

When, by the afternoon of December 6th, Roosevelt recognized that war in the Far East was under way beyond possible recall he decided to send to the Japanese Emperor his appeal for peace which had been discussed with Hull and others but left unsent for some time. He summoned his personal secretary and dictated the final revision of the message to the Emperor which he sent off to Hull to be dispatched to Hirohito. Both Roosevelt and Hull recognized and Hull openly admitted, that this was solely for the record.” That his “record” was understandably much on Roosevelt’s mind during the evening of the 6th is apparent from his remark to Harry Hopkins when Lieutenant Schulz brought him the first thirteen parts of the Japanese reply to Hull’s ultimatum at about 9:30.

It is also highly probable that the report of the very relaxed condition of Roosevelt when he received the message brought by Schulz was also prepared for the “record.” It is repeated by Farago, right on the heels of a crisp summary of how Roosevelt had a few hours before put this country into war, even if not attacked, in violation of his assurances to American fathers and mothers and the 1940 platform and campaign pledges. It is far more likely that Roosevelt’s state of mind was more like that of Wellington who, when on the afternoon of June 18, 1815, Napoleon’s army at the Battle of Waterloo seemed within reach of victory, looked nervously at his watch and, according to the legend, wished “for night or Blucher” (the Prussian general who was bringing decisive armed aid to Wellington.) On the evening of Decmeber 6, 1941, Roosevelt was longing for news of an attack on American forces on one of the three “small vessels” or at Pearl Harbor. These had now exhausted the only possibilities for a surprise Japanese attack on American forces or territory.

The material reviewed in this section makes all the more edifying and illuminating Roosevelt’s remark about 9:30 on Saturday evening, after he read the first thirteen parts of the Japanese reply to Hull: “This means war!” Before 4:00 P.M. on the preceding afternoon, at the very latest, he must have learned that the Dutch had unleashed the fateful chain of events that had put this country into war on the previous Wednesday. His remark to Hopkins that: “We have a good record” does not look so “good” against the facts, implications and results of the Merle-Smith message. Roosevelt’s sole responsibility for the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor may still be debated for years. There is little ground for valid debate in connection with the reality and results of the secret ABCD commitments to the Dutch and British under which he had placed this country and would surely have immediately brought us into active warfare with Japan even if Pearl Harbor had not been attacked.

While the attack on Pearl Harbor may have saved Roosevelt’s political record at home, from the point of view of Japanese military interests it would certainly have been far better for the Japanese to have refrained from attacking Pearl Harbor. They would have gained much more from Roosevelt’s desperate embarrassment end formidable handicaps in being involved in a war that started in the distant East Indies without any attack on American forces or territory or Congressional sanction than they did by sinking the battleships at Pearl Harbor and uniting the country behind Roosevelt’s war effort. War started under such circumstances as the invocation of Rainbow 5 (A2) in behalf of the Antipodes could have provided a Roman holiday for the anti-interventionist forces in the United States led by America First.