AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

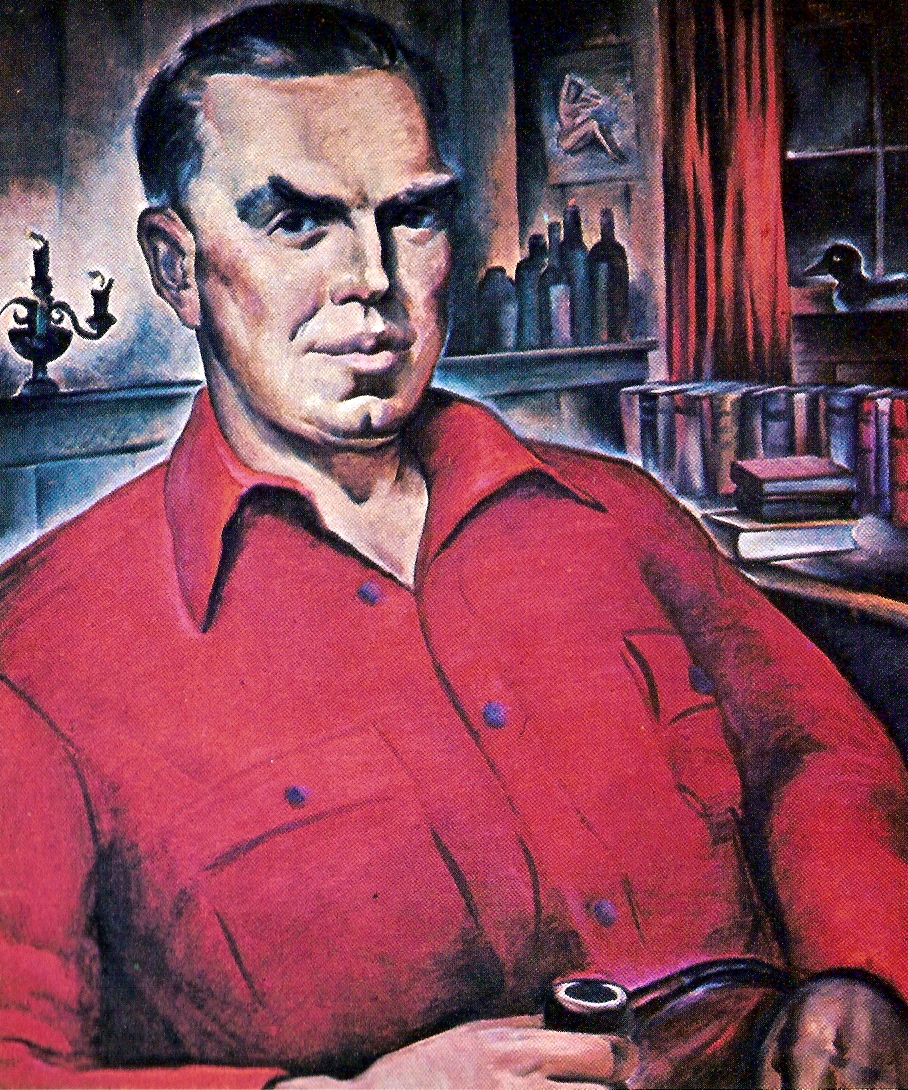

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Pearl Harbor after a Quarter of a Century

Harry Elmer Barnes

IX: Roosevelt Luck!

“. . . Roosevelt’s gamble might have been temporarily frustrated if he had not had aid from across the Atlantic and from, of all persons, Adolf Hitler, through the latter’s idiotically precipitate declaration of war on the United States . . . . If he had been adroit and realistic . . . Hitler would have sent the American people a strong note of condolence over our losses as a result of the ‘treacherous Japanese surprise attack,’ and declared his firm neutrality in the forthcoming war between Japan and the United States. This would have seriously upset Roosevelt’s intrigues with Churchill and their joint arrangements with Russia, as well as gravely hampering and delaying the prosecution of the war in both Europe and the Pacific.”

—Harry Elmer Barnes

On the face of it, President Roosevelt’s daring gamble in providing a Japanese surprise attack on an unwarned Pearl Harbor appeared at the time to be a glorious success. Considering the magnitude of the political stakes in the game he was playing, the loss of a few strategically antique dreadnaughts and the death of three thousand men were trivial, indeed. Roosevelt’s operations had enabled him to bring the United States into the war with a country strongly united behind him. That it turned out in this manner was only because of several strokes of almost incredibly good luck which could hardly been expected and which he did not deserve. But for these the surprise attack might well have proved the major military disaster in the history of the United States.

First of all, was the personality, policy and operations of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, who commanded the Japanese task force that made the attack. He was a member of the Japanese moderate party which wished to keep peace with the United States. He was a personal friend of Saburo Kurusu who had been sent to Washington in the autumn of 1941 to aid Ambassador Nomura for this purpose, and he opposed precipitating war with the United States. Moreover, as a matter of naval strategy, Nagumo never approved of Admiral Yamamoto’s bold plan to attack Pearl Harbor, believing it far too risky and likely to end in disaster. Nevertheless, due to the rigorous Japanese seniority rule, he had to be placed in command of the task force assigned to attack Pearl Harbor although his record as a naval officer was not distinguished.

Nagumo was nervous and worried during the trip from the Kurile Islands to Hawaii. As soon as the successful attacks of the Japanese planes on Pearl Harbor on the morning of the 7th was reported to him, Nagumo ordered the task force to head back toward Japan. If Commander Minoru Genda, who had handled the strategic planning and details of the surprise attack, or Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, who directed the actual attack on the 7th, had been in command of the task force and attacked Pearl Harbor again on December 8th, the Pacific War might have been turned in favor of Japan in the course of the next few days, or even few hours. As the most favorable outcome for the United States, victory could have been postponed for several years, at great additional expense and appalling losses of war vessels and manpower.

The machine shops and other mechanical equipment, the army and navy supplies, and the large store of oil at Pearl Harbor were highly vulnerable to bombing. The oil was still above ground. The planes that remained available at Pearl Harbor after the attack on the morning of the 7th could have put up no decisive resistance to Japanese fighter planes and bombers. The anti-aircraft batteries were not sufficient to repel another Japanese bombing attack, although they might have inflicted more damage than was the case on the morning of the 7th. With the machine shops, military equipment and oil supplies destroyed, the heavy cruisers and carriers that had been sent on to Wake, Midway and Johnston Islands might have been rendered helpless as soon as their oil supply ran out and been captured by the Japanese unless they had been scuttled by their own commanders. The damaged or sunk ships at Pearl Harbor could not have been reconditioned.

Admiral Yamaguchi, commander of the second Japanese carrier division, announced that he was ready to send out fresh planes for a third attack even on the afternoon of the 7th, and those which had been used on the morning of the 7th could have been made ready for a better planned attack on the morning of the 8th. Yamaguchi, Genda and Fuchida begged Nagumo to remain and continue the destruction at Pearl Harbor, but Nagumo refused, and Yamamoto declined to intervene and compel Nagumo to remain and press the attack, which would surely and inevitably have destroyed Pearl Harbor for a year or two, at least, as our great Pacific naval base in the mid-Pacific. To have recaptured Hawaii from the Japanese or defeated Japan from the Western coast of the United States would have been a colossal, prolonged and expensive undertaking and would have seriously reduced or slowed down our effectiveness on the European front.

It has been said that the Japanese could have landed and taken over the Hawaiian Islands immediately after attacks on the 7th and 8th. This is not likely because the task force did not have any landing craft for an extensive occupation. But with the American heavy cruisers and the carriers rendered useless after their oil and gasoline ran out, the Japanese could certainly have returned with all the landing craft and other equipment needed and very possibly taken over the Hawaiian Islands before the United States could have provided successful resistance. To be sure, General Short had an excellently trained army of over 30,000 troops in Hawaii, but with their facilities, equipment end armament devastated by Japanese attacks on the afternoon of the 7th and the morning of the 8th, their effectiveness would have been greatly impaired. All of these possibilities were clearly foreseen in a panicky message sent by the top Washington military brass to the Pearl Harbor command on the morning of December 9th which is described below.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who ultimately succeeded Admiral Kimmel and directed the naval warfare which delivered the decisive victories over the Japanese in the Pacific, agreed with Genda and Fuchida: “Future students of our naval war in the Pacific will inevitably conclude that the Japanese commander of the carrier task force missed a golden opportunity in restricting his attack on Pearl Harbor to one day’s operations, and in the very limited choice of objectives.” Hence, it is no exaggeration to maintain that it was Admiral Nagumo’s timidity, hesitation and lack of strategic vision and courage which transformed Roosevelt’s desperate gamble of goading the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbor from a major national calamity into a great American strategic and political success for the moment.

Nagumo did have some relatively minor considerations to support his hesitation about remaining to renew the attack on the 7th and 8th. He knew that the carriers Enterprise and Lexington were somewhere between Wake and Pearl Harbor with their escorts of heavy cruisers, and he did not know when the carrier Saratoga might be returning from the West Coast. He feared they might all converge on his task force if he lingered to devastate Pearl Harbor and the Army installations. He needed more fuel to indulge in any prolonged further action. His worries were actually unjustified, for Kimmel, right after the attack, had ordered Halsey and Newton to take their station with the two carriers southeast of Wake to await Nagumo’s return and launch an attack on all or a part of his task force, and the Saratoga was only just leaving the West Coast. Nagumo would have been safe in remaining until he destroyed the installations and equipment at Pearl Harbor on the 8th.

Even with the benefit of Nagumo’s stubborn timidity, the naval war with Japan might not have turned out to be a string of naval victories if our naval cryptanalysts had not been able to break the Japanese Naval Code JN-25 for the late summer of 1940 [this date should read 1942—ed.]. Through Commander Rochefort and others it was then possible to supply Nimitz and other naval commanders with the Japanese naval battle plans before the major conflicts. This breaking of JN-25 and earlier Japanese naval codes was a long and slow process, the result of good organization and teamwork rather than the feat of any one genius in cryptanalysts. The work was started by Commanders Safford and Rochefort in 1923-1927 and not completed until late summer in 1940 [again, this date should read 1942—ed]. Further checking was, of course, constantly required to deal with minor changes in the code, new ciphers and the like.

This assertion of the indispensable services of Rochefort and his associates is well confirmed by our defeat at Savo in August, 1942, when our naval forces were commanded by Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner and met heavy losses, only escaping virtual annihilation because the Japanese commander did not recognize the seriousness of the losses he had inflicted. As a leading naval expert on the Pacific War, and himself a crucially important participant, wrote me: Savo was a more disgraceful defeat than Pearl Harbor, but whereas Kimmel, who was surprised in the bargain was dismissed in disgrace, Turner came through his disgraceful performance at Savo in a blaze of glory and was allowed to continue as head of amphibious operations.” My informant did not add that Turner was saved from possible further disgrace later on mainly by the genius of Admiral Raymond A. Scruance our real expert in directing amphibious warfare.

Even with the aid of Nagumo, Nimitz, Safford, Rochefort, and Spruance, Roosevelt’s gamble might have been temporarily frustrated if he had not had aid from across the Atlantic and from, of all persons, Adolf Hitler, through the latter’s idiotically precipitate declaration of war on the United States on the Thursday after Pearl Harbor. Japan had failed to support Hitler in 1939, and especially in the summer and autumn of 1941. Hence, he did not have the slightest moral reason for honoring his formal commitments to Japan in the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis, but had every political and military reason for ignoring them. If he had been adroit and realistic, after the fashion of Churchill and Roosevelt, Hitler would have sent the American people a strong note of condolence over our losses as a result of the “treacherous Japanese surprise attack,” and declared his firm neutrality in the forthcoming war between Japan and the United States. This would have seriously upset Roosevelt’s intrigues with Churchill and their joint arrangements with Russia, as well as gravely hampering and delaying the prosecution of the war in both Europe and the Pacific.

Instead, in one of the most rash, ill-considered and fateful acts of his whole career, Hitler did not wait long enough even to discover the reactions of the American people to the Pearl Harbor attack, once the initial shock of our losses had worn off. He declared war on the Thursday after the Japanese attack on Sunday. This virtually destroyed the possibility of American anti-interventionists being able soon to demonstrate that the attack was due to Roosevelt’s withholding warning information from Pearl Harbor. Of this the Intelligence and Communications operating groups in Washington were well aware at the time and might have leaked the information as a result of their indignation. Somebody, apparently, did leak this information to Dewey’s headquarters in the autumn of 1944.

The directors of America First were actually debating about continuing operations when a rumor of Hitler’s imminent decision on war arrived and frustrated this possible decision. Confirmation of this is contained in a letter written to me by the distinguished American industrialist and railroad magnate, Robert R. Young, on June 2, 1953. Young wished America First to continue even after Hitler’s declaration of war:

I happened to be one of the three dissenting voices when the Directors of the America First Committee voted to disband on the Wednesday after Pearl Harbor. I felt then and still feel that if the Committee could only have been kept going some of these people who will become national heroes could have been made to pay for their sins by their liberty or even by their lives. If the Republicans had not been equally corrupted they could have had the whole damned crowd in jail.

At any rate, Roosevelt’s gamble paid off handsomely for the moment, within the pattern of his bellicose program. Whether it paid off in the long run for the benefit of the United States, the Far East, or the world, can best be left to those who are now assessing our domestic and political crises, the current political and military conditions in the Far East, our military budget, and the battle mortality of men and planes in Vietnam. The Korean War, the wars in the Middle East, the Vietnam War, and the bloody conflicts and confusion in Africa, as well as the communization of Eastern Europe and China and its threat to the Far East, all grew directly our of the second World War and, to a large extent, out of American participation in it.

It might be well to observe in conclusion that Admiral Nagumo may have had his share of good luck as a result of panic and misjudgment at Washington during the days immediately after Pearl Harbor, in which Roosevelt does not seem to have been involved, although Stimson, Marshall, Stark and Turner were.

Immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Kimmel ordered all the craft that could still move at Pearl Harbor to leave at once and join the heavy cruisers, destroyers and carriers that had previously been sent out to Wake and Midway under Halsey and Newton. Rochefort had informed Kimmel that Nagumo would probably deploy some of his task force to attack Wake on his return, and Kimmel ordered Halsey to take his station with the combined forces of the two carriers and heavy cruisers southeast of Wake and await the arrival of any of Nagumo’s task force diverted to Wake.

There was a real possibility of surprising a considerable part of the Japanese task force on its way back to Japan and inflicting serious damage upon it. The total Japanese task force, of course, outnumbered anything the United States could muster at Wake at the time, except in the matter of heavy cruisers, in which we were much superior, but the element of complete surprise might have outweighed this disparity in armament in favor of the United States. Both 126 carriers, the Enterprise and the Lexington, had a complement of planes and plenty of fuel. Since it was unlikely that more than a portion of Nagumo’s task force would be sent to Wake on the return trip, the American force gathered there might have equalled or surpassed the Japanese. It is doubtful if the American forces could have run down Nagumo’s whole task force on the return trip for the latter would have had a considerable head start and had proved to be a fast-moving group of ships.

Admiral Nagumo did not have the slightest precise knowledge as to the actual location of any of the American warships except for those at Pearl Harbor at the time of the attack. But Commander Rochefort, who was in charge of the direction-finding and ship-location operations at Pearl Harbor, knew the location of the returning Japanese task force. He has assured me repeatedly, and no other authority dead or alive could be better informed on the matter, that he believes that the rallied and concentrated American naval force could have inflicted very serious injury on the returning Japanese task force if a substantial portion of it had been diverted to Wake. It might even have accomplished almost as much as was achieved at Midway in June, 1942, thus markedly shortening the time required to defeat Japan. We should recall that the most decisive damage done to the Japanese fleet, especially to their carriers, at the Battle of Midway was accomplished mainly by the planes from the carrier Enterprise, and the Japanese fleet moving on Midway in June, 1942, was vastly larger than Nagumo’s task force that attacked Pearl Harbor. And it was the same Admiral Nagumo who was to lose the battle at Midway by his hesitation and lack of strategic genius, even when he was not surprised. It is likely that he would have proved even more incompetent if he had been surprised and attacked by the American forces in early December, 1941.

All this was nullified by a panicky message sent out of Washington with top priority on the morning of the 9th by Stark and Turner, with the approval of Stimson and Marshall, indicating their belief that there was grave danger that the Hawaiian Islands could not be defended successfully against further expected Japanese raids, ordering that aggressive naval operations around Wake and Midway should be abandoned, and directing that all naval resources controlled by the Pearl Harbor command should be devoted to the defense of the Pearl Harbor area, pending the possible retirement of American forces to the Pacific coast. Washington authorities have sought to defend the panicky message 127 of the 9th by alleging that the Navy could not afford serious damage to or the loss of our two carriers, that the latter had never delivered a successful naval attack, and that the leadership for a carrier operation in war was as yet untested.

The receipt of this message on the 9th led Admiral W. S. Pye, who had replaced Kimmel, to call off the plan that Kimmel had ordered, thus possibly saving Nagumo from undetermined losses, which might have been decisive, and if so preventing the United States from having an early and glorious naval victory that would have more than offset the humiliation and naval losses in the Pearl Harbor attack and notably shortened the war in the Pacific.

This Washington panic relative to the Pearl Harbor situation, until it was evident that the Japanese task force was on its way home and there was no probability of any further immediate Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor, was momentarily so extreme that even some persons of high rank in Washington envisaged an actual Japanese occupation of the west coast of the United States. The United States would then trade space for time and meet the advancing Japanese forces at the crest of the Rocky Mountains, with a final rampart around Denver. Stimson was one of those who were much alarmed and this may have suggested to him the cruel and precipitate action in moving the Japanese off the Pacific coast for which he was mainly responsible.

That Roosevelt was not involved in sending this panicky message of the 9th seems to be proved by the fact that both Secretary Knox and Admiral Beatty, who was Knox’s aide and accompanied Knox on his trip to Pearl Harbor right after the attack, assert that Roosevelt was more disappointed by the cancelling of Kimmel’s plan for operations against Nagumo than he was by the losses at Pearl Harbor. This, of course, raises the question of why Roosevelt did not countermand Pye’s order.