AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

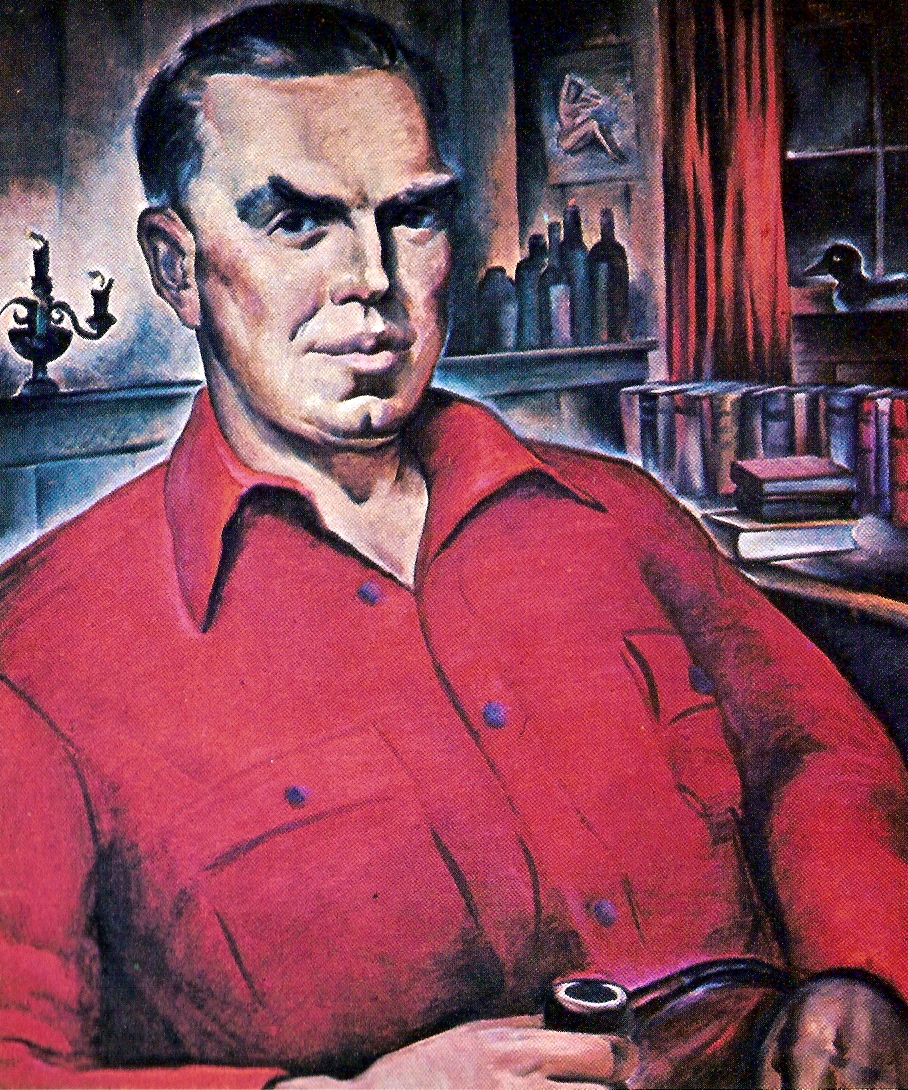

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Pearl Harbor after a Quarter of a Century

Harry Elmer Barnes

II: Roosevelt’s Policies Prior to Pearl Harbor

“. . . Roosevelt . . . had frequently promised that we would not enter any war unless attacked, but the ABCD agreement and the associated war plans were based on the pledge to make war if the situation so demanded without an attack on the United States. At first, this did not worry Roosevelt too much, for he fully expected that Hitler would provide provocative action on the Atlantic in response to illegal American procedure in convoying war materials to Britain and later to Russia. When this did not eventuate and it appeared that Japan would be the actual opponent, it became essential for Roosevelt to do all possible to assure that Japan would provide the indispensable attack that was needed to unite the American people behind him in war. To bring this about it appeared necessary to prevent the Hawaiian commanders from taking any defensive action which would deter the Japanese from attacking Pearl Harbor which, of necessity, had to be a surprise attack.”

—Harry Elmer Barnes

Since this article is to be devoted mainly to explaining why and how Pearl Harbor was surprised on December 7, 1941, we can provide only a very brief summary of Roosevelt’s basic foreign policies and diplomatic actions which bear directly upon this problem.

He was chiefly concerned with the planning and operation of his New Deal domestic policy down to 1937, even to 1939, but he did not forget armament and possible war, even diverting NRA funds to finance naval expansion, chiefly directed against Japan. In early January, 1933, even before he had been inaugurated, and against the urgings of Raymond Moley and Rexford G. Tugwell, he had accepted as the basis of his policy toward Japan the bellicose altitude of Henry L. Stimson which would have led the United States into war with Japan in 1932 or 1933 had Stimson not been checked by President Hoover’s firm stand for peace, a situation explained to me in detail by former President Hoover.

Whenever his domestic policy struck reverses and hard sledding Roosevelt turned to foreign policy with aggressive implications. The first such trend appeared following the rebuff to his main political measures in Congress in 1937, as well as the sharp economic recession that began in the Summer of 1937. It produced the inciting quarantine doctrine of his Chicago Bridge Speech of October 5, 1937. With the outbreak of war in Europe in September, 1939, his aggressive foreign policy continued unceasingly until the attack on Pearl Harbor. Roosevelt’s attempt to purge a no longer docile Congress in the election of 1938 proved an ignominious failure, and the New Deal appeared to be in a permanent slump. It obviously had not solved the depression. Nor had the increasing expenditures for armament succeeded in providing full prosperity.

When war broke out in Europe in early September, 1939, this gave Roosevelt an ominous impulse and continuous inspiration. The war had hardly begun when, on September 11th, Roosevelt wrote Churchill, then only First Lord of the Admiralty, suggesting that they work together through a secret system of communication: “What I want you and the Prime Minister to know is that I shall at all times welcome it, if you will keep me in touch personally with anything you want me to know about. You can always send sealed letters through your pouch or my pouch.” Churchill is said to have responded enthusiastically, including the statement: “I am half American and the natural person to work with you. It is evident that we see eye to eye. Were I to become Prime Minister of Britain we could control the world.” A method of secret communication was agreed upon in which Roosevelt would sign himself “Potus” (President of the United States), and Churchill would sign as “Former Naval Person.” About 2000 messages were exchanged in this way prior to Pearl Harbor, and Churchill is our authority for the statement that the really important negotiations and agreements between Britain and the United States from 1939 to Pearl Harbor were handled in this way, all quite unknown to the American public.

It has since become obvious that while Roosevelt was assuring this country of his peaceful aims he was also actually doing all possible in cooperation with Churchill to get us into war as soon as practicable. In addition to other sources, I have this information personally from Tyler Kent, the code clerk in the American embassy in London, who read all of this material from September, 1939, to the time of his arrest in May, 1941. Two telegrams that have been recovered from this secret correspondence, indicate the tenor and objectives of their collaboration. Roosevelt told Churchill that the United States was firmly isolationist and could not be induced to enter the war in behalf of Poland. Churchill responded: “Every chain has its weakest spot and the weak link in the Axis chain is Japan. Goad Japan into attacking the U. S. and you will have the U. S. in the war.” While this proved to be the strategy followed by Roosevelt, it is unlikely that the policy originated with Churchill.

As Professor William L. Neumann has made clear in his America Encounters Japan (pp. 235-230) this plan to enter a war with Japan, even to provoke Japan to war, was opposed by the overwhelming mass of the American people in the late 1930’s. Even the annual conventions of the American Legion in 1937 and 1938 demanded “absolute neutrality.” The Veterans of Foreign Wars started a campaign to secure 25 million signatures for a petition to “Keep America out of War.” Even the Ludlow Resolution requiring a national referendum on the declaration of war only failed of passage because of the tremendous pressure exerted by Roosevelt through influential public figures.

Despite the strong American isolationist sentiment, Roosevelt never really gave up hope of getting the United States into the war after October, 1937, first and directly in Europe until at least the end of July, 1941. During the spring and summer of 1941 he did everything possible to provoke Germany and Italy to produce some “act of war” in Europe or on the Atlantic that he could use to get the United States into the European conflict, especially through our illegal convoying of munitions and supplies to Britain and Russia, but neither Germany nor Italy would rise to the bait. He had not, however, neglected the possibility of war with Japan. The extensive and quasi-secret increases in the American navy after 1933 obviously pointed the finger at Japan. As far back as the winter of 1937-1938 he had sent Captain Royal E. Ingersoll to Europe to discuss with the English the possibilities of collaboration in the event of war with Japan. In January, 1941, Roosevelt and Hull rejected the amazingly generous Japanese effort to settle Japanese-American relations by peaceful methods presented by a commission with full Japanese authorization. The rebuff of this really sensational overture from Japan seriously undermined the hope of the latter in arriving at a peaceful settlement with the United States, but the effort was continued for over ten months. Japan offered to retire from the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis in return for a guaranty of peace with the United States.

Although Roosevelt had campaigned in 1940 on the basis of promising to keep the United States out of war, he quickly reversed his position. In January, 1941, he sent Harry Hopkins to London to confer with Churchill. Hopkins informed the latter that:

The President is determined that we shall win the war together. Make no mistake about it.

He has sent me here to tell you that at all costs and by all means he will carry you through, no matter what happens to him—there is nothing that we will not do so far as he has human power.

Arrangements were also quickly made for joint-staff conferences with the British to arrange a plan for military collaboration: ABC-1. These were held in Washington from January through March, 1941. In April, another conference was held in Singapore, and this time the Dutch were included to provide for a triangular arrangement: ADB. Combined, they came to be known as the ABCD agreement. The Singapore ADB provided that, if the Japanese moved southward beyond an arbitrary line—100’ East and 10’ North—or even threatened to attack British or Dutch possessions in the Southwest Pacific, the United States would join them in war against the Japanese even though the Japanese did not attack American possessions, forces or flag.

On the basis of this ABCD agreement, the American military services drew up a general war plan known as Rainbow 5, also usually called WPL 46 when used to describe the Navy basic war plan. WPPac46, the U. S. Pacific fleet coordinating plan, governed Admiral Kimmel’s operations. These were promulgated in April, 1941, and orally approved by Roosevelt in May and June. Admiral Harold R. Stark, Chief of Naval Operations, informed his leading commanders that it was no longer a question of whether the United States would be involved in war but only one of when and where. This ABCD agreement and the resulting war plans greatly extended the range of possible provocations to war and provided the first important impulse that led some American military leaders, especially after July, 1941, to consider the likelihood that war might break out in the southwest Pacific rather than by an attack on Pearl Harbor. It thus fatally blurred the basic assumption in our Pacific naval strategy which had long been based on the probability that the Japanese would first attack the Pacific fleet to protect their flank before making extensive military movements in the Far East.

The ABCD agreement also exposed Roosevelt to the possibility of serious political embarrassment. He had frequently promised that we would not enter any war unless attacked, but the ABCD agreement and the associated war plans were based on the pledge to make war if the situation so demanded without an attack on the United States.

At first, this did not worry Roosevelt too much, for he fully expected that Hitler would provide provocative action on the Atlantic in response to illegal American procedure in convoying war materials to Britain and later to Russia. When this did not eventuate and it appeared that Japan would be the actual opponent, it became essential for Roosevelt to do all possible to assure that Japan would provide the indispensable attack that was needed to unite the American people behind him in war. To bring this about it appeared necessary to prevent the Hawaiian commanders from taking any defensive action which would deter the Japanese from attacking Pearl Harbor which, of necessity, had to be a surprise attack.

From March to November, 1941, Roosevelt encouraged Secretary of State Hull to stall the obviously ardent desire of the Japanese, based on self-interest, to arrive at a reasonable and peaceful settlement of Japanese-American relations. By the latter part of July, Roosevelt had about given up hope of getting an act of war from Germany or Italy, and decided to increase pressure on Japan which would make war virtually certain. On July 25th-26th he froze all Japanese assets in the United States and soon placed an embargo on trade with Japan, in which the British and Dutch followed suit, thus facing Japan with economic strangulation unless she could get supplies from the southwest Pacific area, presumably by force.

Washington authorities, especially Admirals Stark and Richmond Kelley Turner, chief of Naval War Plans, recognized that this would force Japan to move rapidly into this forbidden region to secure vital materials which had been placed under an embargo by the ABCD countries. General George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, and Stark sent notices to American commanders in leading outposts that they should take this situation and outlook into serious consideration.

This was a second factor which led many of the top military brass in Washington to shift some of their attention from the traditional Pacific strategy based on a probable Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, even in the face of the Bomb Plot intercepts after September, 1941, which clearly pointed to Pearl Harbor as the first Japanese target. War might start in the Far East. It also helps to account for the fact that the lower or operating units in Army Intelligence and the Signal Corps and in Navy Intelligence and Communications at Washington, who were less fully informed on the partly secret top strategic commitments of ABCD and Rainbow 5 and were devoted to studying the current facts, remained insistent that due attention should be given to the threat to Pearl Harbor and that the Hawaiian commanders should be fully warned of the Japanese menace.

On August 9-12, 1941, Roosevelt met with Churchill at Argentia, off the coast of Newfoundland, and arranged the details of entering the second World War through the backdoor of a war with Japan. Churchill wished immediate war but Roosevelt insisted on having at least three months to “baby” the Japanese along so as to have more time to get ready for war, to allow Russia to take more heat off Britain, and to extend the possibility that Germany or Italy would still provide an act of war on the Atlantic, now that Russia was at war with Germany. These aggressive moves were disguised to the American public by issuing a high-sounding but morally deceptive Atlantic Charter, actually only a press release, the terms of which had been violated before the ink was dry on the document; indeed, by actions before the meeting at Argentia.

The official adoption of the “back door” policy and strategy at Argentia produced a powerful impulse to the top military brass to shift their primary concern to Japan and the Far East. Stark had previously been assuring Kimmel that Germany was our main enemy and that Roosevelt did not wish to get into a two-front war, involving both Germany and Japan. It was now apparent that, if necessary, Roosevelt intended to provoke Japan in the Far East and that the United States would enter the war in this manner. Immediately on his return from Newfoundland, Roosevelt, with the approval of Churchill, called in the Japanese ambassador to the United States, Admiral Kichisaburo Nomura, and administered to him an unprovoked and gratuitous tongue-lashing that even Stimson regarded as an ultimatum. This was done to undermine the Japanese peace party that was still in office, and to strengthen the war party. This aim was fully accomplished when Roosevelt and Hull unceremoniously brushed off the impressive effort of Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoye of Japan to reach a final peaceful adjustment with the United States, including meeting Roosevelt at any reasonable designated spot and accepting in advance the “four principles” that Hull had announced in April, 1941, as the required basis of a peaceful settlement of Far Eastern problems with Japan.

Konoye was replaced as premier by General Hideki Tojo on October 16, 1941. Even the Tojo government offered terms of settlement in November which protected all legitimate American interests in the Far East, but Roosevelt and Hull rejected these, threw over the temporary modus vivendi that General Marshall and Admiral Stark wished in order to complete adequate plans for a Pacific war, and sent to Japan on November 26 an ultimatum which Hull frankly announced took our relations with Japan out of the realm of diplomacy and placed them in the hands of the military: Roosevelt and Secretaries Stimson and Knox. It was recognized by the Washington authorities, who were reading the Japanese diplomatic messages in the Purple code, that this would mean war when the Japanese replied to Hull. Steps were taken to insure that the Hawaiian commanders, General Walter C. Short and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, would not be forewarned of any impending Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor.

Since we shall be mentioning the problem of warning Short and Kimmel, it may be well here to clear up some elementary details. The overall protection of the Hawaiian District, including Pearl Harbor, was entrusted to General Short as commander-in-chief of the Hawaiian District. Cooperating with him was Admiral Claude C. Bloch, commander of the Fourteenth Naval District. His function was to protect the Pearl Harbor naval base. The Naval Communications Intelligence staff, headed by Commander Joseph J. Rochefort, was nominally under the control of Admiral Bloch. Admiral Kimmel was commander-in-chief of the Pacific fleet and the supreme naval authority at Pearl Harbor. His duties were primarily strategic and related to preparing naval hardware and personnel for controlling the mid-Pacific and, if necessary, moving the fleet both to protect Pearl Harbor and to wage war in accordance with orders from Washington based on WPL 46. Important communications from General Marshall, such as warnings of an attack, were sent directly to General Short. Similarly, such warnings from Admiral Stark were sent directly to Admiral Kimmel, who had his own Fleet Intelligence service. Communications from Washington relative to the protection of the Hawaiian naval base at Pearl Harbor were normally sent to Admiral Bloch.

It has been maintained by some critics that Roosevelt was one of the most determined war-mongers of all history. This is a needless overstatement. It is nearer to the truth to state that in his foreign policy Roosevelt was one of the more notable opportunists in the historical record. Churchill may have been an opportunist on domestic policies, but he was consistent in being a partisan of the war.

As Assistant Secretary of Navy under Woodrow Wilson, Roosevelt was an ardent interventionist in regard to the first World War, and later was a strong supporter of the League of Nations. In 1932, he repudiated the League to get the support of Hearst, which was indispensable if he were to win the Democratic nomination. In his campaign of 1936, he described our folly in entering the first World War and questioned Wilson’s wisdom in leading us into it. After the 1936 election, when at Buenos Aires, he condemned nations that maintained prosperity through an armament economy, but by early 1939 he had adopted precisely this program to bolster the New Deal and assure himself a third term.

From this time until Pearl Harbor Roosevelt followed a combined policy of announcing peaceful intentions while planning for war. He informed the American public that he was determined to keep the peace. He told Churchill that he would bring the United States into the war as soon as possible without going so rapidly as to upset their whole plan. His diplomacy all during 1941 was provocative of war, involving this country both in Europe and the Far East, while he was assuring the American public that everything he did was “short of war” and designed to keep us out of war. This brief review provides the essential background against which we must view the developments leading to the attack on Pearl Harbor.