AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

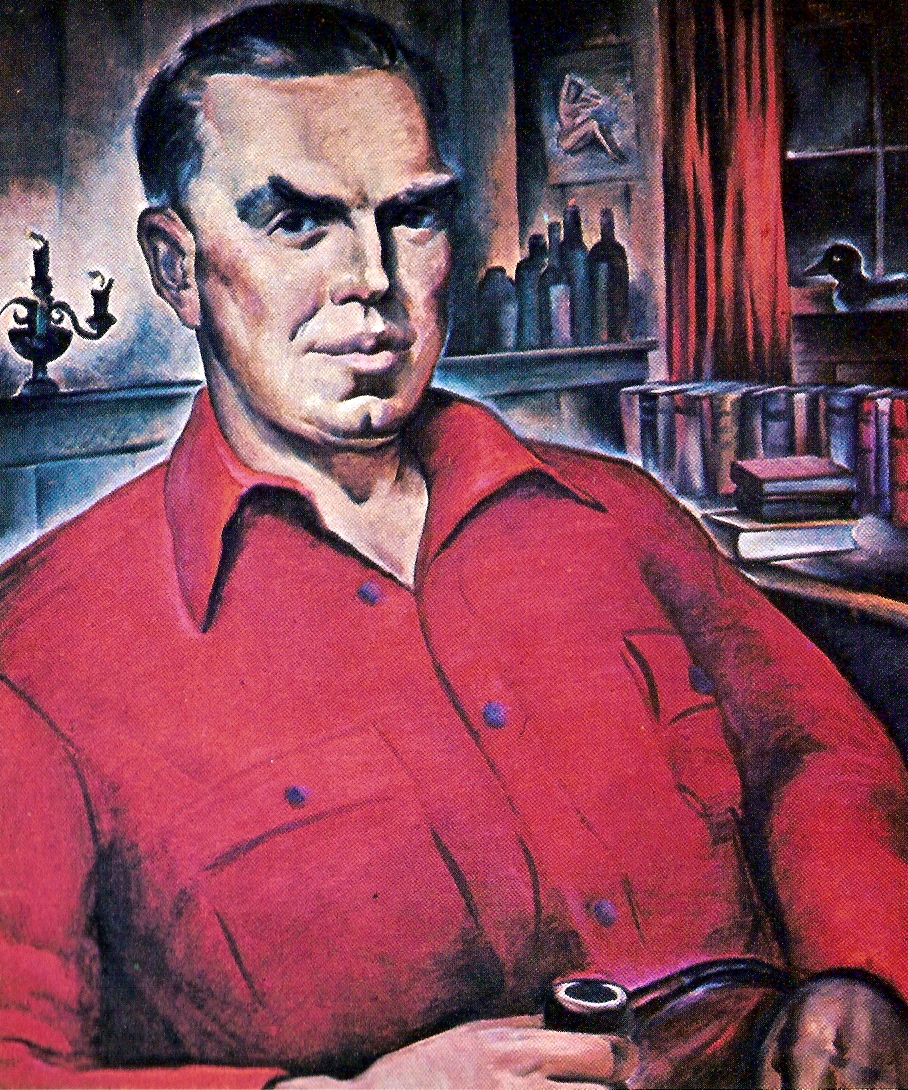

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Pearl Harbor after a Quarter of a Century

Harry Elmer Barnes

III: Washington Should Not Have Been Surprised When The Japanese Attacked Pearl Harbor

“Where [General George C.] Marshall spent the rest of the afternoon and the night of the 6th [of December] has never been determined in any final fashion. When examined in the Joint Congressional Committee Investigation of 1945-1946, although known for his excellent memory, Marshall contended that he could not remember where he spent the night of December 6th, probably the most significant, critical and exciting night of his professional life, at least down to that time. . . . . During the Joint Congressional Committee investigation Senator Homer Ferguson reported to his colleague, Senator Owen Brewster, and to his research aide, Percy L. Greaves, that a few days after Marshall’s attack of amnesia on the witness stand, he overheard Marshall tell Senator Alben W. Barkley, chairman of the JCC: ‘I could not tell you where I was Saturday night (the 6th). It would have got the chief (Roosevelt) into trouble.’”

—Harry Elmer Barnes

1. The Probable Place of a Japanese Attack in the Event of War with the United States

No item in the revisionist presentation of the causes and merits of the second World War is better established than the fact that no top military or civilian authority in Washington on December 7, 1941, should have been surprised at either the place or time of the Japanese attack on the Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor. The only element of surprise, if any, should have been over the damage that the Japanese planes delivered to the fleet.

After the Japanese had abandoned dependence on their Red diplomatic code, which American cryptanalysts had earlier broken, American experts in the Army Signal Corps, directed by Colonel William F. Friedman, had broken the top Japanese Purple diplomatic code by mid-August, 1940, and for a year and a half before Pearl Harbor Washington had been intercepting and reading the secret Japanese diplomatic messages to their officials all over the world. Less difficult diplomatic codes, such as J-19 and PA-K2, were also easily read. Among other things, this breakthrough had enabled the Washington authorities to know that the Japanese peace offers were sincere and not mere window dressing for sinister later designs of an aggressive nature. The Japanese messages also revealed equally clearly that if even extreme Japanese efforts to reach a peaceful settlement with the United States failed, the Japanese would go to war for self-preservation and self-respect. We may first consider the extensive evidence that, if Japan did attack the United States, it would be where the American fleet was then located, namely, at Pearl Harbor.

For years before the attack on Pearl Harbor, naval maneuvers had been held off the island of Oahu in Hawaii to test the feasibility of a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The results were far from reassuring to the United States, and were equally a definite warning of the danger and practicability of a Japanese task force attack there. As early as 1932, Admiral Harry E. Yarnell, one of our earliest air-minded naval officers, made the first carrier-based task force test and he was able to execute a surprise attack when operating only sixty miles off Pearl Harbor. These maneuvers were continued, and in 1938 a successful air attack was launched from the carrier Saratoga one hundred miles off Pearl Harbor. The Japanese task force in December, 1941, operated from over 200 miles away. In April, 1941, General Frederick L. Martin and Admiral Patrick N. L. Bellinger, commanders of the Army and Navy air forces respectively at Pearl Harbor, described in detail the nature of a possible Japanese air attack on Pearl Harbor which was uncannily identical with Yamamoto’s plan for the actual Japanese attack a few months later. This was forwarded to the Army and Navy headquarters in Washington but no positive response or protective operation took place.

Long before Admiral Kimmel assumed command at Pearl Harbor in January, 1941, it had become basic in Pacific naval strategy to accept the fact that if the Japanese ever started a war with the United States they would first strike our Pacific fleet, especially if based at Pearl Harbor, to protect their flank before they could safely move large naval forces south or north from Japan. This had been constantly emphasized to Washington from the time of the assertions of General Hugh Drum in 1935 and of General George V. Strong in 1940, to the observations in 1941 of Commander Arthur N. McCollum, head of the Far Eastern Section of Naval Intelligence, the man who had probably the best informed conceptions of the naval and diplomatic situation in the Far East, with the possible exception of Colonel Otis K. Sadtler of the Army Signal Corps and Colonel Rufus S. Bratton, Chief of the Far Eastern Section of Military Intelligence.

Viewed most generally, then, it had long been assumed that the Japanese would not go to war with the United States without first protecting their flank by trying to destroy the American Pacific fleet, wherever it was stationed. It was also clear that the American fleet would be both more inciting and more vulnerable to a Japanese attack if stationed at Pearl Harbor, as compared to its relative safety before the spring of 1940, when it had been based on the Pacific coast of the United States, mainly at San Diego. Admiral James O. Richardson, Kimmel’s able predecessor as commander of the Pacific fleet, bitterly protested the fleet’s permanent retention at Pearl Harbor, after maneuvers in the spring of 1940, and labelled Pearl Harbor “a damned mouse trap” for the American navy.

Indeed, it is certain that Richardson’s untimely removal as head of the fleet was brought about by his determined resistance to what he considered the folly of keeping the fleet at Pearl Harbor. Admiral Frank E. Beatty, a well informed authority, has told me that it may also have been due in part to the animosity of Harry Hopkins, who sat in on Richardson’s conferences with Roosevelt. Richardson was annoyed by Hopkins’ interjection of his opinions into the debate and understandably commented unflatteringly on Hopkins’ lack of qualifications as an authority on naval strategy.

Added to this generalized conception of our Pacific naval strategy centering around Pearl Harbor was a precise statement from our Ambassador in Tokyo, Joseph C. Grew, in January, 1941, that he had received a friendly warning from the Peruvian Minister in Tokyo, which the latter had obtained from several sources, one Japanese, to the effect that, if Japan could not reach peaceful relations with the United States, it would start war by a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. After the successful Japanese attack on December 7, 1941, the Washington authorities, who were desperately trying to cover up their bad guessing or actual guilt, tried to represent this warning as worthless hearsay, but it was not so regarded by Ambassador Grew and some top Washington officials in January, 1941, notably Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox.

It was not necessary, however, to rely on generalized strategic considerations, however sound. From September, 1941, to December 7th Washington authorities intercepted a considerable number of Japanese messages between Tokyo and Honolulu that specifically and most obviously indicated that, in the event of war between Japan and the United States, the first Japanese move would actually be a surprise attack on the Pacific fleet—that Pearl Harbor would be the target. These messages came to be known as the “Bomb Plot” messages and consisted of requests from the Japanese government in Tokyo to the Japanese consul-general in Honolulu, Nagoa Kita, for detailed and specific information as to the nature, number and types of vessels in the Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor, their location and movements, and other relevant information connected with the American military establishment located there, together with Kita’s replies to these requests. These requests from Tokyo to Kita became more insistent, frequent and detailed as we approach December 7, 1941.

The first of these was sent in the J-19 Japanese code to Kita on September 24, 1941, and was decoded, translated and read on October 9th at Washington. This requested very detailed information on the composition, location, and operations of the Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor. From this time onward, Washington should have had no doubt that the Japanese were planning a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, if negotiations failed. The Bomb Plot messages clearly pinpointed Pearl Harbor as the target of any Japanese surprise attack on the United States.

When relations became more tense after the fall of the Konoye Cabinet in October, 1941, Tokyo ordered that these espionage reports from Kita should be sent at more frequent intervals. On November 15th, Kita was ordered to send his reports twice each week. On November 18th and 20th, orders were given to inform Tokyo in regard to all our warships and others anchored in areas adjacent to Pearl Harbor. On November 29th, Kita was ordered to make his reports, even though there had been no movements of the warships at Pearl Harbor.

No such detailed or comprehensive reports, containing as they did grids and coordinates, were demanded of any Japanese officials and spies at any other American outpost or naval base anywhere in the world, not even those on the Pacific coast. Those who have sought to minimize the significance of these Kita Bomb Plot messages have pointed out that Japanese spies were frequently detected making inquiries at leading American naval bases but these were routine and trivial matters and not in any way to be compared or rated with the Kita messages. All these Bomb Plot messages were available to the appropriate top Washington officials in the Army and Navy and to Roosevelt and Hull, and they thoroughly established the probability that if the Japanese made any surprise attack on the United States it would be at Pearl Harbor.

The most crucial Kita report available in Washington before Pearl Harbor was sent to Tokyo by Kita on December 3rd. He informed the Japanese government that he had set up an elaborate system of window code signals at Lanikai Beach which were easily visible to boats off the coast. From this spot he would signal passing Japanese fishing craft and submarines as to the nature and movements of the Pacific fleet. These boats and submarines could then pass this vital information back to the Japanese task force as it was nearing Pearl Harbor for the attack.

This sensational and revealing message was intercepted at the army monitoring station at Fort Hunt, Virginia, on the 3rd, was decoded by Naval Communications in Washington before noon on the 6th, and was translated and ready for reading and distribution before 2:30 P.M. on that day. This finally confirmed the pin-pointing of Pearl Harbor as the place of the Japanese attack. Due to the fact that the Kita message implied that the signals would end on the night of the 6th, this December 3rd intercept also clearly indicated that the Japanese task force under Admiral Nagumo was moving on toward Pearl Harbor and intended to organize off Oahu on the night of the 6th, and make ready for the attack on Pearl Harbor the next morning. Hence, this message not only made it clear that Pearl Harbor would be the place of the Japanese attack but also revealed the time of this attack, unless something happened to slow down or divert Nagumo’s expected arrival on the 6th as anticipated.

How far Roosevelt, Hull, and the top military brass in Washington were informed of the nature, contents and implications of this vital and revealing Kita message that was available on the 6th has, naturally, been the subject of much controversy. It was actually far more revealing than the fourteen-part reply to Hull and the Time of Delivery message as to the time, place and certainty of an immediate Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. If it could be proved that its contents had been known to the top officials in Washington by early evening of the 6th, then their failure to warn Kimmel and Short would appear to be far more culpable than that connected with the replies to Hull that were not available until the late evening of the 6th and the morning of the 7th, and even then did not make the time and place of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor anything more than trained and informed guesswork. Hence, there would be every effort to indicate that no information about this Kita message was available until after the attack.

Certain of the important facts about the Kita message are established beyond any reasonable doubt. Its interception on December 3rd has been described. It was decoded some time between the 3rd and 6th and was given to the translating section of Naval Communications for translating. This was done by a Mrs. Dorothy Edgers, a competent expert on the Japanese language, between 8:00 A. M. and 2:30 P. M. on the 6th. Her immediate superior was Yeoman Bryant, and the chief of the section was Commander Kramer. Both of these men knew during the time that Mrs. Edgers was working on the translation that she regarded it as a very important document and that she gave it careful attention. She was supposed to leave at noon, but was so much interested in the document that she worked until after 2:00 P.M. to complete and revise her translation. She handed it over to Yeoman Bryant to discuss with Commander Kramer with respect to its distribution to top-level civil and military officials entitled to receive such material. While there is controversy over whether Kramer read the Edgers’ translater [i.e., “translation”—A.F.] carefully, there is little doubt that Bryant did so. The main dispute is over whether Kramer distributed the message to at least a few key officials in the Army and Navy on the afternoon of the 6th.

The accepted legend is that when Kramer looked over the Edgers’ translation after she left the office he found that it was so imperfect that it was unsuitable for immediate distribution. The excitement that followed with the arrival of the Plot Message and the Japanese reply to Hull, together with Kramer’s responsibility for distributing the reply to Hull during the evening of the 6th, made him decide to delay reworking the Edgers’ translation until Monday, the 8th, when it was too late to be of any value in warning Kimmel and Short.

The circumstantial evidence tends to support the probability that Kramer read the Edgers’ translation well enough to recognize its great and immediate significance and showed the message to some of the leading officers in the Navy, and possibly in the Army, and was ordered by these persons, who recognized its importance, to suppress it for the time being. Mrs. Edgers was a competent translator and she remembered the essential parts and the full implications of the message well enough so she could describe the contents on the witness-stand some three and a half years later without ever refreshing her memory by seeing the document during that long interval. If she could remember the message, it is likely that Kramer could have quickly grasped its significance.

He was familiar with the Bomb Plot messages from the time of the first one decoded on October 9th, the importance of which he was the first to recognize. Since the reply to Hull was in English, Kramer did not have to be busy translating this on the afternoon of the 6th and should have had plenty of time to study the Edgers’ translation and call it to the attention of his responsible superiors. Kramer was the most severely intimidated of all the witnesses in the post-Pearl Harbor investigations—to the extent of bringing on a nervous breakdown. Hence, he was not likely to come clean in his testimony on the Kita message if he did suppress it. He has declined to answer personal questions on the matter since his retirement. Although Yeoman Bryant was present in the room during the investigation he was not called to testify.

Hence, we are likely to remain as much in the dark about documenting the distribution of this final and most sensational of the Bomb Plot messages as we are about Captain Kirk’s frustrations in regard to the first one on October 9th. The best discussion of the controversy to reach print is that by Commander Charles C. Hiles which was published in the Pearl Harbor supplement to the Chicago Tribune on December 7, 1966, the twenty-fifth anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Why these Bomb Plot messages were not sent to Hawaii by the Washington authorities, so they could be used by Kimmel and Short and enable them to be prepared for the Japanese attack has never been adequately explained. In naval headquarters at Washington, they were suppressed chiefly by Admiral Richmond Kelley Turner, whose ignorance of the details of the cryptanalytic set-up and operations at Pearl Harbor was only exceeded by his arrogant self-confidence, and Admiral Stark backed him up instead of keeping his promise to Admiral Kimmel to have him fully and speedily informed on all such matters. At the army headquarters the responsibility was mainly that of General Marshall and General Sherman Miles, chief of Military Intelligence. Until December 3rd, most of these messages were intercepted by the Army Signal Corps station MS5 at Fort Shafter, General Short’s headquarters near Honolulu, and were transmitted to Washington for decoding, translation and reading. They were also usually intercepted at several other monitoring stations in the United States.

When the first one was decoded, translated and read on October 9th, Commander Alwyn D. Kramer, who was in charge of the translation work for the Far East section of Naval Communications, noted that this was a very significant message that needed further study. It must have received such study for Captain Alan G. Kirk, the able, forthright and experienced Director of the Office of Naval Information at the time, insisted that the October 9th message must be sent to Admiral Kimmel. He was blocked in this proposal by Admiral Turner, who was supported in this by Admiral Stark. Frustrated and disgusted, Kirk left his post and sought the sea duty he needed to become an admiral, and later rendered very distinguished service in naval operations in Europe. The details of Kirk’s leaving for sea duty have been furnished to me in person by Admiral Beatty, at that time chief aide to Secretary Knox.

It is most unfortunate that Admiral Kirk was not thoroughly interviewed after the war concerning the refusal of Stark and Turner to permit him to transmit this first Bomb Plot message to Kimmel. I had arranged to have this done in 1962 when Kirk was residing in New York City. Being on the opposite side of the continent at this time, I could not do it personally, but had arranged that a trained interviewer and an expert on Pearl Harbor would carry it out. He delayed briefly to make more complete preparation, and in the meantime Kirk was appointed American ambassador to Formosa (Taiwan). Another student of the situation, without my approval, took the chance of writing Admiral Kirk in Formosa about the incident. It was hardly to be expected that Kirk could give any detailed answer under these circumstances. He might well have been expected to ignore the letter but he gave a courteous reply, making no categorical denial and thus by indirection implying that he may have been prevented from transmitting the information to Kimmel. He soon retired due to ill-health, was then in no condition to accept the request for an interview, and died soon after his retirement. This ended the possibility of clearing up the October problem in any final and definitive manner. That the situation in the Office of Naval Intelligence was confused in 1941 is evident from the fact that by the end of October there had been four chiefs of this organization: Captains Anderson, James, Kirk and Wilkinson.

It is certain that Turner was directly responsible for frustrating Kirk, but there is no proof that this was the result of any conspiracy to keep Kimmel in the dark. Turner was a very able but conceited officer, sure of himself. His mind was mainly on the Atlantic, and so far as the Pacific was concerned he still believed that the Japanese would attack Siberia. He was unpardonably ignorant about Pearl Harbor intercepting facilities at the time, actually believing that it had a Purple machine and was reading the Japanese diplomatic messages on the spot. The main responsibility for Kirk’s frustration was, however, that of Stark, who had promised Kimmel that he would transmit to him all significant information about any possible Japanese menace to Pearl Harbor, and Kirk had been fully informed of this. Why Stark deferred to Turner in this episode has never been cleared up. Admiral Beatty informed me that Turner often dominated Stark in the matter of naval decisions. Stark refused to clarify matters in a long interview with Percy Greaves in mid-December, 1962. It has been alleged on good authority that an attempt was made to falsify the Naval Directory for 1941 to indicate that Kirk had left his post as Director of ONI before October 9, 1941.

Kirk was succeeded by an able but far less experienced and more pliant person, Captain Theodore S. Wilkinson, who may have feared to repeat Kirk’s insistence with Turner. This has come to be known as “the October Revolution” in the Office of Naval Intelligence. In any event, both the Army and Navy Departments had these crucial Bomb Plot messages at hand and if they neglected them, then it was no less than a criminal neglect and it was an important factor in leading to the destruction of the Pearl Harbor fleet. The place—and through the Kita message of December 3rd even the probable time—of the Japanese surprise attack no longer needed to be a mystery. Not only the Japanese inquiries as to the fleet, facilities and supplies at Pearl Harbor but also the general strategic logic of all the circumstances connected with the launching of a Japanese war against the United States at any time, and especially in 1941, made it all but certain that the first drastic move would be against Pearl Harbor. Japan did not need to be attacked to start a war, as Roosevelt did. It needed to destroy the American Pacific fleet, and it would be difficult to do this after war had started elsewhere. Admiral Kimmel would then deploy and scatter his forces as they moved to Wake, Midway and the Far East and they would never again be bunched up as they were at Pearl Harbor in peacetime.

It should also be emphasized that although the treatment of the Bomb Plot messages in the preceding pages has stressed the role of the Navy in receiving and handling them, the Army also obtained them, and alert officers therein were impressed as Captain Kirk had been by the threat to Pearl Harbor which they revealed. Colonel Rufus S. Bratton, chief of the Far Eastern section of Military Intelligence, delivered the original Bomb Plot message, decoded on October 9th, to Secretary of War Stimson, General Marshall and General Leonard T. Gerow, chief of the War Plans division of the Army. These messages were discussed by officers in Military Intelligence and the Signal Corps and most of them recognized the desirability of sending them to General Short at Fort Shafter, but they were no more able to get past Marshall and do so than Kirk, Wilkinson, Noyes and McCollum could get by Turner and Stark. Just as Turner was the chief navy obstacle to getting the Bomb Plot messages through to Kimmel, so Marshall constituted the main blockage in passing them on to Short, although he could delegate the action to General Miles, chief of Military Intelligence. Marshall was also the person mainly responsible for the slow transmission of the Bomb Plot messages from MS5 at Fort Shafter to Washington, compelling them to be sent by the China Clipper, every two weeks, or by ordinary boat mail, when they could have been sent at once by cablegram or RCA radiogram. In other words, General Short was as much victimized as Admiral Kimmel in being deprived of these vitally important Bomb Plot messages.

2. The Time of the Japanese Surprise Attack

Washington also possessed extensive and diversified advance knowledge of the time when the Japanese would attack Pearl Harbor; by the morning of December 7th almost to the minute when the attack would be launched. The Kita message, which had been prepared for distribution by 2:30 P.M. on the 6th, also indicated even more directly that the attack would in all probability take place on the morning of the 7th.

On November 5th, Tokyo informed the Japanese embassy at Washington that negotiations must be satisfactorily concluded by November 25th. Unknown to Washington was the fact that the latter was also the date that the Japanese task force was getting ready to leave the Kurile Islands for Pearl Harbor if negotiations were broken off, but with orders to return if negotiations were resumed. On November 14th, Tokyo informed the Japanese consul at Hong Kong that Japan would declare war on the United States and Great Britain, if the negotiations with the United States failed. On November 11, 15 and 16, Tokyo repeated to the Japanese ambassador in Washington that the deadline for completing negotiations with the United States was November 25th. On November 22nd this deadline was extended to the 29th, but the Japanese embassy in Washington was then emphatically informed that Tokyo meant business this time and there would be no further extension of the deadline. After that “things are automatically going to happen.” On November 27th and 28th, Tokyo informed the Japanese embassy in Washington that Hull’s ultimatum of November 26th was entirely unsatisfactory and Japan would not negotiate any further on that basis. Hull himself had said on the 27th that he knew his ultimatum meant war and that henceforth, affairs between the United States and Japan were in the hands of Stimson and Knox, the Secretaries of War and the Navy, both of course under the control of President Roosevelt. On November 30th, Tokyo informed Germany that negotiations with the United States had ended.

Yet, on November 27, 28, 30 and December 1st there was a succession of messages from Tokyo to the Japanese embassy in Washington warning them not to reveal that negotiations were over, but to indicate they were being stretched out. This move was both a last ditch attempt at a peaceful settlement and, if that failed, an effort to cover up the actual nature of “the things that are automatically going to happen” after negotiations had ended, which was really on the 26th. These “things” were the departure of the Japanese task force from the Kuriles to Pearl Harbor. There had been no effort whatever to conceal the extensive movement of large Japanese convoys and task forces to the southwest Pacific, and, hence, these were clearly not the things which were “automatically going to happen.”

The policy of sending extensive Japanese convoys and task forces southward helped to distract responsible attention in Washington from a possible attack on Pearl Harbor, even if it should not have done so, and thus worked well for the Japanese program. This was one reason why many top officials in Washington seemed to neglect the traditional Pacific strategy in regard to Pearl Harbor and the Bomb Plot messages and after early November concentrated most of their attention right down to December 7th on the probability of an attack in the Far East, either on the Philippines, along the coast of southeast Asia, or on the British possessions and the Dutch East Indies. A little thought should have been sufficient to convince the Washington authorities that Japan would not be likely to make its first major onslaught in the Far East. Admiral Thomas C. Hart’s Asiatic fleet was so small that its destruction would not protect the Japanese flank from a major and immediate American naval attack.

The most important factor in this distraction from Pearl Harbor was the basic strategic plan for a possible Pacific war with Japan, Rainbow 5 (WPL 46), which had been drawn up by our military services on the basis of the Washington joint staff conferences ending with that at Singapore in April 1941, and confirmed orally by Roosevelt in May and June. This plan was based on the assumption that, if war came with Japan, it might start in the Far East as a result of American commitments to come to the aid of the British and Dutch, even if there were no attack on American ships or territory. This naturally helped to divert the attention of top military brass in Washington from the traditional Pacific strategy related to an attack on the Pacific fleet, wherever located, especially during the week before Pearl Harbor.

Washington had all the numerous intercepted Japanese diplomatic messages indicating by November 27, 1941, that war was in all probability only a matter of days away, but Kimmel and Short knew nothing whatever about any of this. They did not even know that Hull had sent an ultimatum to Japan on November 26th or that the Japanese had warned that negotiations were to be ruptured on the 29th if no settlement had been arranged. They obviously knew nothing about the details of the Japanese-American diplomatic negotiations from August to November 26th; Short was in the dark after July.

By November 27th, war with Japan seemed almost certain, and it was expected in Washington official circles that it would probably come coincident with the Japanese reply to Hull’s ultimatum. Since Japan usually made its surprise attacks on a weekend, when opposing forces were most likely to be relaxed and off-guard, some Washington authorities, including Roosevelt, thought that the attack might come on November 30th, but that was too soon for Japanese plans, which were centered on the task force’s departure from the Kuriles and its movement toward Pearl Harbor. When the Japanese did not attack on the 30th, there was special apprehension in Washington that it might come on December 7th, but no plans were made or steps taken to warn Kimmel and Short of this possibility.

On November 19th, the Japanese announced in their J-19 diplomatic code, which we could and did read, the setting up of a so-called Winds System, which Japanese diplomatic officials and consulates could intercept and learn of Tokyo’s intentions in the event of breaking off diplomatic relations and going to war with the United States. The Winds signals were as follows: “East Wind Rain” for the war on the United States; “West Wind Clear” for war on Great Britain; and “North Wind Cloudy” for war on Russia. This Winds system, as we shall see, was executed on December 4th.

Evidence of the approach of war became ever more apparent after November 30th. On December 1st and 2nd it was learned that Tokyo had ordered its main embassies, with the exception of that at Washington, to destroy their main code machines, including Purple, and burn their documents. This was a measure that usually precedes immediate war and is rarely, if ever, otherwise if ordered on any such scale as in December, 1941. The Washington Purple machine was to be retained until December 7th so that Tokyo could keep in touch with the Japanese embassy and be able to send Ambassador Nomura the reply to Hull, which would be the last “peaceful” communication, even though it would also mean, in all probability, the actual onset of war.

On the morning of December 4th a Japanese message was intercepted at the important naval monitoring station at Cheltenham, Maryland. This did not need to be decoded for it was written in plain Japanese language and was transmitted in the Japanese Morse code. This was done in order to enable Japanese officials, who were without decoding equipment after the codes-destruction order, to be able to understand this critical message. This intercept was the all-important execution of the Winds system set up by Japan on November 19th. It is known as the “Winds Execute” message and the information therein revealed that war would be made on the United States and Britain, but not on Russia.

Later on, when the frenzied effort was made to cover up the responsibility for the failure of Washington to inform Kimmel and Short, there was a desperate attempt made to deny that any Winds Execute message had ever been received, and most—perhaps all—copies of it were destroyed. The last copy ever seen was identified by Commander Laurance F. Safford when Commander Kramer was assembling documents for the Roberts Commission a week after the Pearl Harbor attack. But honest and courageous experts, notably Safford, chief of the Security Division of Naval Communications, who had received the intercept from Kramer after translation and handed it over for distribution, stuck by the facts and demolished all efforts to repudiate the authenticity of Winds Execute. Safford was able to list some fourteen persons, including Admiral Thomas C. Hart, commander of the Asiatic fleet, who said that they had seen the Winds Execute message or had discussed it with a responsible official who had seen it. The Naval Court of Inquiry, which met from July to October 1944, established beyond any doubt that the Winds Execute message was received on December 4th. Colonel Otis K. Sadtler, acting chief of the Army Signal Corps, not only testified that he had seen the Winds Execute message but said that he regarded it as the most important intercept he had ever handled. On it he based a forthright warning to Marshall’s subordinates, presumably with Marshall’s approval. The investigations by the Army Pearl Harbor Board and the Clarke Inquiries indicated that the Army authorities knew that the Navy had intercepted the Winds Execute message on December 4th.

Some of the apparent excitement and confusion which seemed to prevail in Washington military circles on December 4th, when Winds Execute was received, may have been due to the fact that this was also the day that the Chicago Tribune published the implications of Rainbow 5, thus revealing Roosevelt’s deception of the American people as to his war plans and his promise not to go to war unless attacked. At least we know that Marshall was far more concerned about this vital leak than he was about the reception of Winds Execute. Colonel John R. Deane was still working on this problem when he saw Marshall in his office at 10:00 on the morning of the 7th.

Winds Execute was not only the first explicit assurance that Japan was going to make war, but it also made it clear that the war would be declared against the United States. All that remained to be revealed was the moment of the Japanese attack, and it was expected that this would be when the Japanese handed in their reply to Hull’s ultimatum of the 26th, which turned out to be the case.

It was not necessary to wait long. The final and decisive Kita Bomb Plot message, sent to Tokyo on December 3rd, was intercepted at Fort Hunt, Virginia, on the same day. By December 6th it was decoded, translated and available for distribution at 2:30 P.M. in the communications section of the Navy Department in Washington. This revealed that the Japanese task force was nearing Pearl Harbor and was expected to arrive off Hawaii by the night of the 6th.

On the heels of processing the Kita message came the so-called Pilot Message from Tokyo, which announced that Japan was sending to the Japanese embassy in Washington its ominous and anxiously awaited reply to Hull’s ultimatum. The Pilot Message was decoded, translated and ready for distribution before mid-afternoon on the 6th and enabled the Washington authorities to know that the Japanese reply to Hull was arriving, that negotiations were over, and that war was now at hand. The whole fourteen-part message told little more than this, aside from a summary of the negotiations. There was no doubt that Japan would attack the United States in a matter of hours. Short and Kimmel should have been warned at once. This would have provided their last fair and decent opportunity to take action to avert, evade or repel the Japanese attack. Of course, they should and could have been warned weeks earlier, and certainly by November 27th.

Some thirteen parts of a total of fourteen in the complete reply to Hull came in during the afternoon of the 6th, were decoded from the Purple code, and were ready for distribution by that evening. Since the reply to Hull was in English it did not need to be translated. A copy was delivered to Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins at the White House about nine o’clock that night. After reading it, Roosevelt acknowledged that it meant war but he took no steps to order any warning sent to Pearl Harbor. As we shall point out later on, Roosevelt knew by the forenoon of the 6th, if not on the 5th, that the United States was already at war with Japan due to our commitments to the British and Dutch under ABCD and Rainbow 5.

The thirteen-part message was delivered on the evening of the 6th to the available Army officers entitled to Magic and to Hull under the supervision of Colonel Rufus S. Bratton, chief of the Far East section of Military Intelligence of the Army, and to the appropriate Navy officers, except for Stark, who was at a theater, by Commander Alwyn D. Kramer of the Far East section of Naval Communications. A copy for Marshall was left by Bratton with Colonel Walter Bedell Smith, who was Marshall’s secretary and the man short of Roosevelt himself, most likely to know where Marshall was to be found. It was Smith’s duty to deliver such messages to Marshall.

The final or fourteenth part, also in English, arrived during the night of the 6th and was decoded by early morning on the 7th. It confirmed the Pilot Message’s implication that negotiations between Japan and the United States were over, hardly news to Washington. Following this fourteenth part of the reply to Hull was another and far more important short message from Tokyo, the crucial so-called Time of Delivery message. It ordered the Japanese ambassador, Admiral Nomura, and his associate, Kurusu, to deliver the full fourteen-part Japanese reply to Secretary Hull in person at 1:00 P.M., Washington time, about 7:30 A.M. Pearl Harbor time.

The fourteenth part was intercepted, decoded, and ready for distribution by 7:30 A.M. and the Time of Delivery message by 9:00 A.M., if not earlier. One authoritative report indicates that both were ready for distribution before 7:00 A.M. They had been received before 5:00 A.M. This does not make too much difference because Admiral Stark did not get to his office before 9:00 and General Marshall was either on a horseback ride or hiding out in some place. When these late intercepts were shown to Admiral Stark; chief of Naval Operations, about 9:00 by Admiral Leigh Noyes, chief of Naval Communications, Captain Wilkinson chief of Naval Intelligence, and Commander McCollum chief of the Far East section of Naval Intelligence, they pointed out to Stark that 1:00 P.M. in Washington was about 7:30 in Pearl Harbor and that this could very well mean that the Japanese would attack Pearl Harbor at 1:00 P.M. Washington time. Stark had four hours remaining in which to warn Kimmel, whom he could have reached in ten minutes or less by his fast naval transmitter, but he ignored the appeal of Admiral Noyes, Captain Wilkinson and Commander McCollum that he send a separate warning to Kimmel, and did nothing for the time being beyond phoning to Roosevelt, who certainly did not order him to warn Kimmel.

Marshall’s conduct on the morning of the 7th was even more mysterious than that of Stark. According to the accepted legend, supported by sworn testimony of himself and prominent army associates, he abruptly left his office in the old Munitions Building on Saturday afternoon right after he learned from the Pilot Message that the Japanese reply to Hull was about to start coming into Washington, which was exactly the moment Marshall should have settled down in his office, warned Short of the prospect of immediate war, and spent the night with him discussing the best manner of dealing with the imminent attack. Of course, if he had given Short an honest and adequate warning on November 27th, there would have been no attack to discuss on the night of the 6th.

Where Marshall spent the rest of the afternoon and the night of the 6th has never been determined in any final fashion. When examined in the Joint Congressional Committee Investigation of 1945-1946, although known for his excellent memory, Marshall contended that he could not remember where he spent the night of December 6th, probably the most significant, critical and exciting night of his professional life, at least down to that time. Later on, after his wife had gallantly refreshed his memory, Marshall stated that he spent it at home with Mrs. Marshall, who was recovering from an accident at the time. During the Joint Congressional Committee investigation Senator Homer Ferguson reported to his colleague, Senator Owen Brewster, and to his research aide, Percy L. Greaves, that a few days after Marshall’s attack of amnesia on the witness stand, he overheard Marshall tell Senator Alben W. Barkley, chairman of the JCC: “I could not tell you where I was Saturday night (the 6th). It would have got the chief (Roosevelt) into trouble.”

Continuing the official legend, the next morning Marshall rose leisurely, had a late breakfast with his wife, and then took a long horseback ride when, for all he is alleged to have known, the Japanese could have already attacked the United States. While washing up after his return from the relaxing ride, he was summoned to his office by Colonel Bratton, who had been greatly alarmed by the clear implications of the Time of Delivery message relative to an attack on Pearl Harbor.

Arriving at his office about 11:25, so the story goes Marshall allegedly read for the first time the fourteen-part reply to Hull and the Time of Delivery message, and decided to send a warning to Short, which he did at 11:50. Despite more rapid means of communication that were available, it was sent by Western Union to San Francisco and from there to Hawaii by RCA, not marked urgent, and was not actually put on the wires until 12:17. It did not reach Short until after the Japanese planes had returned to their carriers, over 200 miles from Pearl Harbor. This delay in delivery did not, however, make too much difference, since the message was sent far too late, even if telephoned, to have given Short enough time to have taken effective steps to repel the Japanese attack and it did not even suggest to Short that there was any reason to expect that a Japanese attack might take place immediately. Kimmel and Short thus remained entirely unwarned even after leading experts in both Army and Navy Intelligence had concluded by around 9:00 A.M. that the fourteen-parter and the Time of Delivery messages meant that the Japanese would probably attack Pearl Harbor at about 1:00 P.M., Washington time.

Another much different version of Marshall’s activities from mid-afternoon on the 6th to noon on the 7th appears to be far closer to the truth than the traditional legend and it is supported by persons of unimpeachable integrity. This version also accepts the fact of the complete mystery of Marshall’s disappearance from the mid-afternoon of the 6th to the morning of the 7th and our lack of precise knowledge as to where he was during all this time, when he should have been constantly in touch with Short at Fort Shafter. But it does eliminate the horseback ride and Marshall’s incredibly late arrival at his office on the morning of the 7th. Colonel John R. Deane, then an aide of Colonel Walter Bedell Smith, who was Marshall’s secretary at the time, has asserted that he saw Marshall at his office at about ten o’clock on the morning of the 7th. Commander McCollum has twice stated once under oath that Marshall came to Stark’s office with a military aide about 9:00 that morning. Marshall and Stark, along with others in Stark’s office, notably Admiral Noyes, discussed the fourteen-part and Time of Delivery messages, and formulated the message that was to be sent to Short by Marshall. Admiral Stark asked, later that morning, that the message sent to Short should also be handed on to Kimmel.

Marshall delayed sending this message for nearly two hours after he left Stark’s office, thus making it too late to enable Short to go on an alert that might frighten off the Japanese attack, and did not hand over his message to be sent to Short until 11:50. He further assured its late delivery by refusing to use the quick methods provided by his scrambler telephone connection with Short or the more powerful Navy and F. B. I. transmitters which were offered to him. It was sent by Western Union at 12:17 from Washington to San Francisco and from there to Short at Fort Shafter by R. C. A., not even marked urgent, with the results noted above.

Both versions of Marshall’s conduct on the morning of the 7th agree upon the content of the “warning” message Marshall finally sent to Short and make it clear why it has been dubbed the “too-little-and-too-late” message. This is the message:

Japanese are presenting at one p.m. Eastern Standard Time what amounts to an ultimatum also they are under orders to destroy their Code machine immediately. Just what significance the hour set may have we do not know but be on the alert accordingly. Inform naval authorities of this communication.

Marshall

There was nothing in the message to indicate any immediate emergency for Pearl Harbor or that there was any knowledge or conviction at Washington that the Japanese might be attacking Pearl Harbor within about an hour. Marshall deliberately deceived Short in telling that the significance of the Time of Delivery message was unknown. Even Admiral Samuel E. Morison admits this. Actually, when Marshall read over the fourteen-part reply to Hull and the Time of Delivery message, his associates in his office state that he exclaimed, “This means immediate war!” There was no such interpretation, even by way of implication, in what he sent to Short, and the same message was to be transmitted to Kimmel. That Marshall was capable of sending a clear and incisive warning when he wished to do so is shown by the message he sent to General Herron, the commander of the Hawaiian District, on June 17, 1940. In what was little more than a practice alert to impress the Japanese Marshall ordered Herron to: “Immediately alert complete defensive organization to deal with possible trans-Pacific raid.”

The defenders of Roosevelt and Marshall have contended that Marshall knew nothing of the fourteen-parter or the Time of Delivery messages until he read these in his office after 11:25 on Sunday morning. To accept this requires the utmost credulity, even naivete. If he did not know about them, then this proves carelessness and callous indifference to his official duties quite sufficient to justify his dismissal from office as Army chief-of-staff. He needed to be well informed about these documents just as much if he were to practice clever deception as though he were doing his duty in getting the facts and cooperating with Short in meeting the Japanese attack. Roosevelt would not have allowed him to get out of touch with Army Intelligence or the Signal Corps. There is no reasonable doubt that Marshall, informed of the Pilot Message, had arranged for receiving these messages, had read them, and was fully informed by the time he reached his office or Stark’s on Sunday morning whatever time that was. This is the only reasonable explanation of why he sought an early conference with Stark. Those who have sought to indicate otherwise are better known for their proclivity to cover up the facts in this situation than for their zest for revealing the truth. The only reasonable motive for Marshall’s disappearance would have been to make himself inaccessible to those who might plead with him to send a warning to Short and Kimmel.

Another important qualification bearing on the validity of the traditional account of Marshall’s conduct on the morning of December 7th has been pointed out by Commander Hiles. He made a very careful estimate of the time which would have been required for Marshall to have done all the things he is stated to have accomplished in the twenty-five minutes between 11:25 and 11:50 in his office on the morning of December 7th, and conservatively concluded that it would have required at least two hours.

There is no space here to go into the complicated question of where Marshall was from mid-afternoon of the 6th until 11:25 on the morning of the 7th, when he is represented as reaching his office in the Old Munitions Building to examine for the first time the messages that had come in from Japan during this interval. I sought to do this as well as possible in the Pearl Harbor Supplement published by the Chicago Tribune on December 7, 1966. It is obvious that one must choose between the traditional legend and the statements of Admiral McCollum, made during the post-Pearl Harbor investigations, and before a luncheon at the Army and Navy Club in Washington on May 3, 1961, as reported in the notes of Admiral John F. Shafroth that were twice checked and confirmed with minor revisions by Admiral McCollum. They are also supported by the statement of Colonel (now General) Deane that he saw Marshall at his office about 10:00 A. M. on the morning of the 7th, and by a direct report to me by Professor Charles C. Tansill who was present at the meeting on May 3rd.

It obviously makes a great deal of difference, factually, whether Marshall was off on a horseback ride during the morning of December 7th and did not reach his office until 11:25, where he first saw the reply to Hull and the Time of Delivery message, or whether he came to Stark’s office shortly after 9:00 on the morning of the 7th, discussed the reply to Hull and the Time of Delivery message with Stark, McCollum, Noyes and Wilkinson, formulated there the warning to be sent by him to Short before 10:00 A.M., but delayed sending it until 11:50 that morning.

Personally, I prefer to accept the statements of Admiral McCollum as being far better supported by documentation and circumstantial evidence and motivated only by a courageous desire to establish the truth. Most of the documentation supporting the traditional story has been destroyed or kept a close secret. On December 17th General Sherman Miles, chief of Military Intelligence, prepared an honest account of what went on in Marshall’s office on the morning of December 7th and showed it to Marshall. It made the latter furious and he banished Miles to the post of military observer in Brazil and allowed him to stay in the service on condition of making no further revelations. Later on, Marshall summoned the officers who were acquainted with the facts to a room, locked the door, walked around the room, shook hands with each of those present, and told them that the facts relating to the events of December 6th and 7th and associated developments must remain a secret with them “to the grave.” One of those present decided not to have this situation on his conscience until he reached the grave and revealed the facts to Professor Tansill and myself. Whatever Marshall did on the morning of December 7th, it was all too late for any effective warning of Pearl Harbor.

It is probable that even revisionist historians have erred in putting exclusive emphasis on the Time of Delivery message as the sole or best basis for deciding that the Japanese would attack Pearl Harbor on the morning of the 7th. Intelligence experts like Bratton and McCollum did this only by clever guessing and logical inference. But the Kita message, which was ready in all essential parts for distribution by 2:30 P.M. on the afternoon of the 6th, left nothing to guesswork. Kita’s complex system of signals to be passed back to the approaching Japanese task force was to end on the night of the 6th, clearly implying that the task force was expected to be arriving at Hawaii by the night of the 6th, organizing off Oahu and put in readiness for the attack the next morning.

Such was the situation in Washington. There was an impressive accumulation of evidence by the morning of December 7th which made it certain that war with Japan was coming in a matter of a few hours, with every probability that the attack would be made on Pearl Harbor. Even as early as December first, it was probable that war was about to start somewhere, and by December 4th it was certain that Japan would attack the United States. Surely, by then, it was mandatory to warn Short and Kimmel in clear and definite fashion. If they had been so informed on the 4th they would have taken steps to go on an effective alert that would have led the Japanese task force to turn back. It was not until December 5th that Tokyo sent its vital radio message directing Admiral Chiuchi Nagumo (who commanded the Japanese task force) to “climb Mount Niitaka,” which meant that he was to proceed to Pearl Harbor with no further delay or interruption unless negotiations were resumed.

Of course, Short and Kimmel should have been told of the negotiations with Japan in November, 1941, and warned when Tojo began to set deadlines for the end of these negotiations, notably after he set November 29th as the date when they must be settled unless “things were automatically going to happen.” But neither Kimmel nor Short received any warning whatever of an impending Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor until the Japanese bombing planes appeared over the fleet and the military establishment about 7:50 on the morning of December 7th.