AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

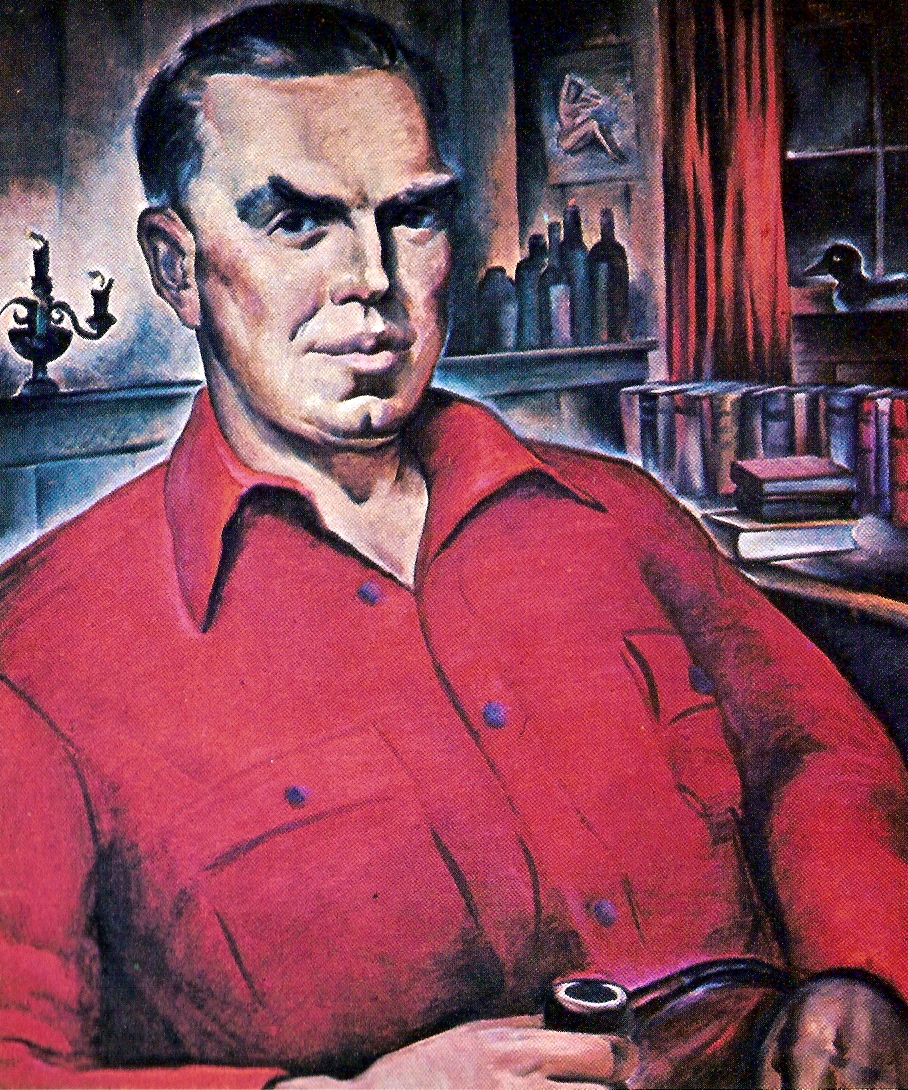

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Pearl Harbor after a Quarter of a Century

Harry Elmer Barnes

IV: Keeping Short and Kimmel in Ignorance of a Surprise Japanese Attack

“[General Walter C.] Short was a personal friend of Marshall . . . . He had every reason to believe that Marshall would keep him thoroughly informed of any information available in Washington that was of vital significance for Pearl Harbor. . . .

[Admiral Husband E.] Kimmel had even more personal reasons to believe that he would not be double-crossed or blacked out by Washington. He had been an aide to Roosevelt when the latter was Assistant Secretary of the Navy under Wilson and had maintained pleasant relations with him after that time. He was an especially close friend of [Admiral Harold R.] Stark, who was then Chief of Naval Operations, the supreme authority over naval affairs. . . . In June [1941], Kimmel went to Washington, had a long talk with Stark, and the latter assured him that he would be furnished with full information about all developments of interest to Pearl Harbor and by the most rapid methods which were also secure.”

—Harry Elmer Barnes

We may now turn to the account of the incredible extent to which General Short and Admiral Kimmel were kept in ignorance of any Japanese threat to Pearl Harbor down to the moment of the attack. Both these men had special personal reasons to believe that Washington would keep them informed of any developments that directly endangered Pearl Harbor.

Short was a personal friend of Marshall, and like Marshall one of the few important generals who was not a West Point graduate, and he had been promoted and placed in charge of the Army establishment in Hawaii by Marshall. He had every reason to believe that Marshall would keep him thoroughly informed of any information available in Washington that was of vital significance for Pearl Harbor. Probably, he should have begun to have some doubts about this before December, 1941, in the light of the manner in which Washington ignored his demands for material and equipment to complete the defensive installations that were required, and the almost complete failure to send planes that he needed for reconnaissance and repelling Japanese bombing attacks. Short received no information about intercepts of the Japanese Purple diplomatic code after the economic measures taken against Japan at the end of July, 1941.

Kimmel had even more personal reasons to believe that he would not be double-crossed or blacked out by Washington. He had been an aide to Roosevelt when the latter was Assistant Secretary of the Navy under Wilson and had maintained pleasant relations with him after that time. He was an especially close friend of Stark, who was then Chief of Naval Operations, the supreme authority over naval affairs. Soon after Kimmel succeeded Admiral Richardson as commander of the Pacific fleet, he wrote Stark in February, 1941, that he would expect to be sent all relevant information collected by Naval Communications and the Office of Naval Intelligence. In March, Stark promised that this would be done, and that Captain Kirk, the able and alert Director of the Office of Naval Intelligence, fully understood this to be one of his most important duties. There can be no doubt that Kirk intended to keep Kimmel informed and that his being blocked in this by Turner and Stark when the first Bomb Plot intercept was decoded in early October was a main reason why he resigned as head of the Office of Naval Intelligence and sought sea duty. In June, Kimmel went to Washington, had a long talk with Stark, and the latter assured him that he would be furnished with full information about all developments of interest to Pearl Harbor and by the most rapid methods which were also secure.

There is good reason to believe that Stark meant to do this, but his hands were tied in many ways. He was a genial and modest person, and had the bad luck to be closely associated with Admiral Turner, chief of Naval War Plans, who, while a mentally superior officer, was also an arrogant, conceited, overbearing and opinionated bully. He tended to override Stark, almost to the extent of assuming to be in charge of the Navy. Admiral Beatty, who, as aide to Secretary Knox, attended many top naval conferences, told me that, more often than not, when Knox asked a question of Stark, Turner would do the answering. He regarded his own opinions as more reliable than the facts, of which he was often careless. He even believed that Pearl Harbor had a Purple machine and could decode Japanese diplomatic messages on the spot. Until mid-November, 1941, he labored under the obsession that Japan would move into Siberia and attack Russia rather than make war in the southwest Pacific. There is no doubt that Turner did more than anybody else in the Navy to prevent the Bomb Plot messages from getting to Kimmel and to frustrate the efforts of Commander McCollum to warn Kimmel decisively in the days immediately before the Pearl Harbor attack. How far he was directly influenced by Roosevelt in this is not revealed in the documents.

Stark kept up a friendly correspondence with Kimmel down to December, 1941 and from this Kimmel learned indirectly most of what little he knew about the negotiations with Japan, but Stark stressed the fact that the only actual threat of war in the Pacific existed in the Far East and never at any time even implied any direct menace to Pearl Harbor. While he sometimes mentioned our negotiations with Japan, he would never go into detail or indicate the sources of the information about our diplomatic dealings since this information was derived from our Magic operations which Stark has always maintained he was not allowed to divulge. In June, 1961, Stark told two college professors, Paul Burtness and Warren Ober, that he had to swear a “horrendous oath” which superseded all other oaths, never to divulge the existence or contents of Magic operations.

Kimmel had never heard of the Purple machine or of our breaking the Japanese Purple code. Pearl Harbor had been denied a Purple machine in the summer of 1941, when the one which was originally designed to go to Pearl Harbor was sent as a “spare” to London, which already had two Purple machines. But Kimmel had been given clearly to understand that he would immediately obtain all information of any significance in safeguarding his operations at Pearl Harbor and believed he was getting it. Actually, Kimmel never received any of the intercepts from the diplomatic messages in the Purple code after the meeting of Roosevelt and Churchill at Argentia early in August, 1941, and no details about Japanese-American negotiations at any time.

On the whole, one may assume that Stark personally wished to keep Kimmel informed so far as he could without violating his orders from Roosevelt about Magic and other secret restraints. When accused of improper action, Stark’s invariable defense was that he always acted in accordance with a “higher authority,” who could only have been Roosevelt. He was often confused himself, partly by Turner and partly because he became one of those who seemed to be both beguiled by the movement of Japanese forces down the southeastern coast of Asia and distracted by the strategic implications of the naval war plan WPL 46, derived from ABCD and Rainbow 5, which envisaged war in the southwest Pacific. He actually may have come to believe that the first Japanese attack would surely take place in the Far East. Of course by December 4th, Stark was hogtied by Roosevelt’s order that all warnings to Pearl Harbor must be cleared through Marshall, and on the night of the 6th and the morning of the 7th Roosevelt may have seen to it that Stark was reminded of this order by telephone.

The truth of the matter is that Short and Kimmel never received any of the intercepted Japanese messages in the Purple code that would have told them of the diplomatic negotiations with Japan during the autumn of 1941. Without these the mention of such items as the “ending of diplomatic negotiations” could not make any real sense to them or cause any serious alarm.

Kimmel and Short were not even sent the Bomb Plot messages that were obtained between September 24th and December 7th, although they were sent in the J-l9 and PA-K2 codes which were less secret than Purple and could have been read at Pearl Harbor at any time by Commander (now Captain) Joseph J. Rochefort, Admiral Bloch’s talented and experienced cryptanalyst and Communications Intelligence officer, if he had been assigned this duty. These Bomb Plot messages, as we have seen, pinpointed Pearl Harbor as the first target of any Japanese Surprise attack. If these had been read by Rochefort they would have been even more of a warning of a direct Japanese threat to Pearl Harbor than the Purple diplomatic messages some of which actually encouraged top naval authorities in Washington to believe that if there was any war with Japan it would probably start in the Far East.

Most of these Bomb Plot messages were picked up by the Army Signal Corps station MS5, located at Fort Shafter, General Short’s army headquarters near Honolulu. The station was actually controlled and operated by Colonel Carroll A. Powell operating under the Army Signal Corps in Washington. Kimmel did not even know that Station MS5 existed. Short knew it was stationed at Fort Shafter but he did not know what it was actually doing. He had been informed that it was operated by the Army Signal Corps at Washington and, hence, assumed that if anything of significance to Hawaii was picked up by MS5 the information would be sent back to him from Washington, which never actually occurred.

Station MS5 intercepted the Japanese messages to and from Tokyo and Honolulu as raw and undecoded material, and, at Marshall’s order, sent them on by mail to Washington, making use of the China Clipper from Honolulu to San Francisco which made the trip once every two weeks. When the Clipper missed a trip they were sent by boat mail which further slowed down their arrival in Washington. These Bomb Plot messages were also usually intercepted by the Navy monitoring station S at Bainbridge Island on Puget Sound, and by the Army Signal Corps Stations MS2 at the Presidio in San Francisco, and MS7 at Fort Hunt, Virginia. Duplicates of these intercepts were thrown away, depending on the time of their arrival in Washington. Those retained were decoded, translated, read and filed away. Their nature and crucially important contents were never revealed to General Short or Admiral Kimmel.

Colonel Powell had no personnel capable of decoding and translating these Bomb Plot messages, and they would not have dared to do so without authorization if they had been able to do so. But, as we have noted, Admiral Bloch had in Commander Rochefort a trained and veteran cryptanalyst—one of the very best in the Navy—and a master of the Japanese language who could have decoded and translated these J-19 messages with great ease if he had been assigned to do this as one of his duties. But he was kept very busy at research work on Japanese naval codes, direction-finding, and traffic analysis. It was customary for these specialists in cryptanalysts and related operations to stick to their own assignments. Therefore, Rochefort, who did know that MS5 existed, would not have considered investigating its operations and would not have been welcomed if he had done so.

If he could have received these J-19 and PA-K2 messages that carried the Bomb Plot material, decoded and translated them, and turned them over to Kimmel and Short, there can be no reasonable doubt that these commanders would have taken defensive actions long before November 25th that would have called a halt to Yamamoto’s plan to send a task force to attack Pearl Harbor.

Commander Rochefort has told me that if he could also have had the diplomatic messages sent in the Purple code he would have been even more impressed with the significance of the Bomb Plot messages and, in that event, Pearl Harbor would most surely have gone on an alert in ample time to have led to the cancellation of Yamamoto’s attack program. Even some of the Purple material that he needed for this was also actually being intercepted at MS5 and transmitted to Washington, but Rochefort could not have decoded and translated this in the autumn of 1941 because Pearl Harbor had been denied a Purple machine for the benefit of the British. Hence, it is both paradoxical and calamitous that the very material which would have frustrated the attack on Pearl Harbor was intercepted right at Hawaii but could not be used there, by either the design or the stupidity of Washington, mainly that of the Army officials, specifically, General Marshall himself.

As to the precise attitude and opinion of the military authorities at Pearl Harbor concerning the probability that the Japanese would start a war with the United States in 1941, I have discussed this matter several times with Captain Rochefort, twice with Admiral Kimmel, and once with General Short. Admiral Kimmel assured me once more in June, 1966, that he and Short were in agreement on this. Lacking any specific warning information whatever from Washington or any other reliable source, they had to make up their own minds from general considerations. It seems perfectly clear that all the responsible personnel at Pearl Harbor rather completely discounted the probability of war with Japan. They arrived at this conclusion because they did not believe that Japan would be unwise enough to start a war that it could not ultimately win. The resources of the United States were so great that we would ultimately wear down Japan, even if we did not win a quick and brilliant victory. They were proved to be right about this, but not about Japan’s willingness to risk defeat if they started a war.