AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

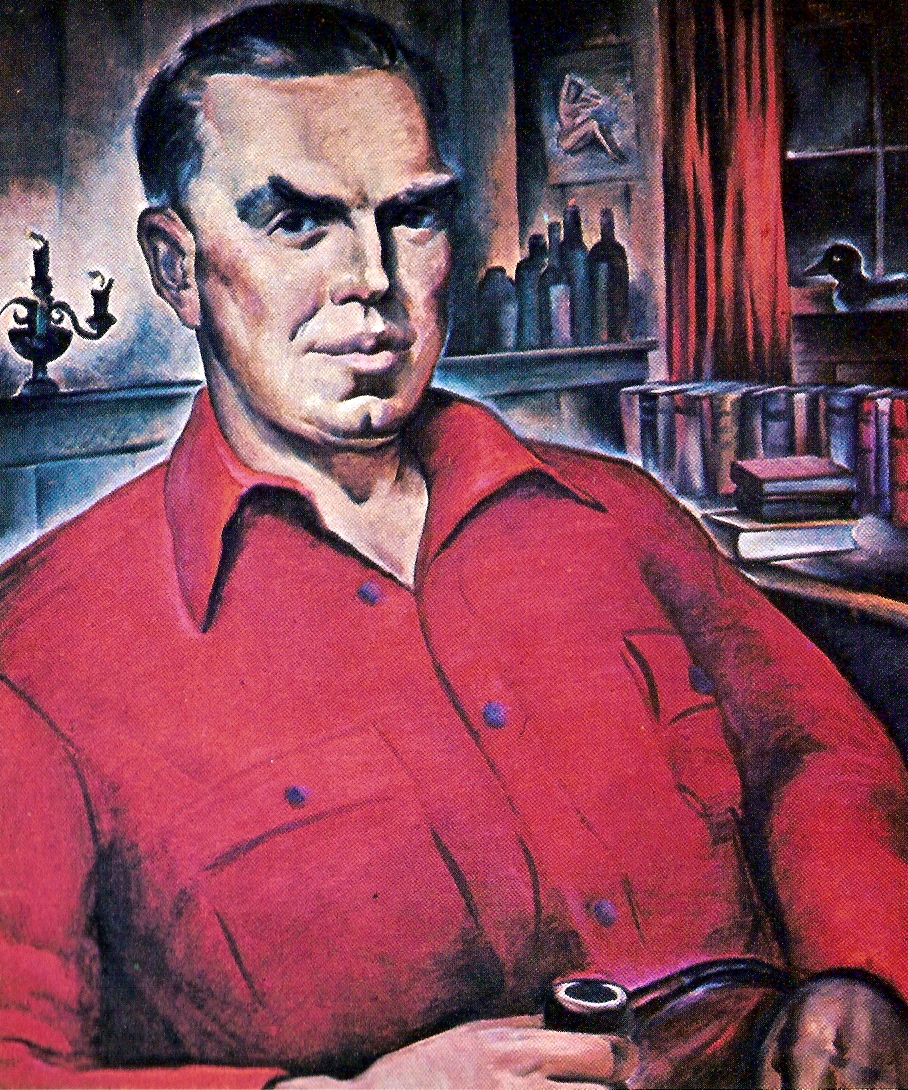

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Pearl Harbor after a Quarter of a Century

Harry Elmer Barnes

V: The So-Called Warnings to Short and Kimmel

“

[General] Short and [Admiral] Kimmel have been vigorously criticized on the ground that . . . they did not . . . recognize the probability that . . . the Japanese would first attempt a surprise attack on the American Pacific fleet, wherever it was stationed . . . . As a matter of fact, they never lost sight of this possibility . . . .

From the time Kimmel assumed command at Pearl Harbor in February, 1941, both he and Short had frequently mentioned and discussed the possibility . . . and recognized the action and supplies needed to detect and turn back such an attack. They had vainly requested the equipment required effectively to carry out such a protective policy . . . but they had received virtually nothing . . . . General Frederick L. Martin and Admiral Patrick N. L. Bellinger, commanders of the Army and Navy air forces in Hawaii, handed in a report about the feasibility and danger of a Japanese surprise air attack on Pearl Harbor that was virtually identical to the plan Yamamoto actually carried out . . . . It was carefully studied by Short and Kimmel and was forwarded to Marshall in Washington on April 14th but without any response directing appropriate defensive operations at Pearl Harbor or supplying adequate equipment.”

—Harry Elmer Barnes

Now that we have seen that Short and Kimmel were denied the extensive body of valid and relevant information which would have enabled them to learn of the probability of a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in ample time to have taken proper action to have averted or repelled it, we may consider the so-called “warnings” that were sent to them. These have been presented by the defenders of Roosevelt, Stimson, Marshall and Stark as clear and precise warnings that Pearl Harbor was definitely threatened by an imminent Japanese air attack, and it has been asserted that if Short and Kimmel had taken proper cognizance of the information they would have been prepared for the Japanese attack that came on the morning of December 7th. Actually, these so-called warnings to Short and Kimmel on November 27th and 28th were nothing of the sort. Commander Hiles has stated the reality clearly: “A genuine, forthright, and honestly inspired war warning can be expressed most lucidly, concisely, intelligently and forcibly in one sentence—the shorter the better. The warnings to Short and Kimmel were lacking in all these virtues. They were probably the most profuse collection of misleading verbiage ever to grace two military messages that purported to warn two important field commanders of a war already known in Washington to be a fait accomcli.” They were a great contrast with the warning that Marshall had sent to General Herron in Hawaii in June, 1940.

On November 27th, General Short received from Washington the following message which has been represented as a warning of approaching war, with the direct implication that he was being informed of a probable attack by Japan “at any moment”:

Negotiations with Japan appear to be terminated to all practical purposes with only the barest possibilities that the Japanese Government might come back and offer to continue. Japanese future action unpredictable but hostile action possible at any moment. If hostilities cannot, repeat cannot be avoided the United States desires that Japan commit the first overt act. This Policy should not, repeat not, be construed as restricting you to a court of action that might jeopardize your defense. Prior to hostile Japanese action you are directed to undertake such reconnaissance and other measures as you deem necessary but these measures should be carried out so as not to alarm civil population or disclose intent. Report measures taken. Should hostilities occur you will carry out the tasks assigned in Rainbow five so far as they pertain to Japan. Limit dissemination of this highly secret information to minimum essential officers.

The message just cited did not even imply any threat of a Japanese attack at Hawaii. It stated that negotiations with Japan, of which Short had no specific knowledge, had come to an end, with little prospect that the Japanese would renew them. Hostile action, which could have meant either distant war or local sabotage, might start at any time, but it was essential that Japan must commit the first overt act. Prior to any hostile act, Short was to take all protective measures deemed necessary, but they must not alarm the civil population. If hostilities did start, Short was to operate in accord with War Plan Rainbow 5, so far as it applied to Japan.

The message to Short bore Marshall’s signature although he was away from Washington that day watching maneuvers in North Carolina. Its inception was conceived by Secretary Of War Stimson, possibly at Roosevelt’s suggestion, and it was written by Stimson and General Leonard T. Gerow, chief of Army War Plans, with some aid from Colonel Charles W. Bundy of the Army General Staff. They consulted Roosevelt, Hull and Knox, Admirals Stark, Turner, and Ingersoll, and General William Bryden, Deputy Army Chief of Staff. Commander Hiles has appropriately observed that it was both strange and suspicious that such a large group and range of top level signatories had to be assembled if the purpose was actually to formulate a clear and precise warning of imminent war, which could have been prepared by any bright second lieutenant or ensign in ten minutes. To prepare a war warning that was not a war warning required, however, the pooling of much skill in obfuscation and deception. From the statements of Stimson and Gerow, it appears certain that the message was originally conceived and formulated to guide General MacArthur in the Philippines, to whom substantially the same message was sent. It was also sent to the Caribbean Defense Command in the Panama Canal zone and to the Fourth Army headquarters at the Presidio in San Francisco.

Short logically replied to the November 27th message as follows: “Department alerted against sabotage.” His reply was read by Stimson, Marshall and Gerow. Since Short received no reply from Washington he correctly assumed that these men were satisfied with his report.

Three other messages were sent from Washington to Fort Shafter on the 27th and 28th, amplifying the directions as to measures to be taken by Short against local sabotage. One was sent by General Sherman Miles, chief of Army Intelligence in Washington, to Colonel Kendall J. Fielder, chief of Army Intelligence in Hawaii; one by Adjutant General Adams to Short, and one by General Henry H. Arnold, chief of the Army Air Corps in Washington, to General Frederick L. Martin, chief of the Hawaiian Air Force. All of these indicated to Short that he had been correct in instituting an alert against local sabotage.

These messages merely added more detailed directions as to how Short should apply his alert against local sabotage. They stressed the need to assure security against the danger of hostilities, by which was plainly implied local subversive activities in Hawaii, to avoid publicity and not excite the public at Honolulu, and to maintain strict legality in all actions. To the Army authorities in Hawaii, it appeared obvious that the main fear in Washington, as expressed in the messages to Short and his subordinates, was that subversive activities, such as rioting in Honolulu, might produce some overt act by Americans that Japan could regard as justifying a declaration of war. The United States could then be accused of having precipitated war without any attack. It was Roosevelt who, personally, directed that the stipulation that Japan must be permitted to commit the first overt act of war should be included in the message to Short of November 27th and in that of Stark to Kimmel on November 29th. This was the basic formula of Roosevelt as the situation approached hostilities, and was immortalized by the statement of Stimson in his Diary after the meeting of the War Cabinet on November 25th: “The question was how we should maneuver them [the Japanese] into the position of firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves.”

On November 29th and December 4th, Short and Martin sent detailed reports to Marshall and Arnold, as to the manner in which they had carried out the directions on instituting and operating the alert against local sabotage. Once more, there was no reply from Washington, and Short again felt assured that Washington was satisfied with what they were doing in Hawaii. Marshall admitted, when being examined by Senator Homer Ferguson during the Joint Congressional Committee Investigation in 1945-46, that Short was entirely correct when he assumed that, since there were no replies to his reports on the operations he had instituted to check local sabotage, what he had done was fully satisfactory to Washington.

In assessing the nature and significance of these bogus “warning” messages to Short, one may well start with pointing out that they were not in any way even labelled as a “war warning.” Nothing indicated any thought of war at Hawaii. It is obvious that the vague reference to Japanese hostility in the message to Short had been inserted for the benefit of MacArthur who was located at the Philippines in the Far East, the area where the authorities in Washington were becoming ever more convinced that, if any Japanese attack occurred, it would take place. This overlooked the fact that an attack on the Philippines and the destruction of Hart’s small fleet would not serve the main purpose of the first Japanese attack, which was to destroy the Pacific fleet and protect the Japanese flank against their further campaigns in the Far East.

The emphasis in all four messages to Short was placed primarily on watching and suppressing local subversive activities and on handling such operations with care and with studied legality. Subversive activities were obviously what were meant by “hostilities,” so far as Hawaii was concerned, although they doubtless envisaged possible military activities in the case of MacArthur. This throttling of subversive activities was to be effective but executed with restraint and caution. Neither any subversive activities nor Short’s restraint of them should be allowed to get out of hand and make it possible for Japan to regard some extreme incident as an overt and plausible “act of war,” which, according to Roosevelt’s policy, must be left for the Japanese to provide.

All this restraining action must be so executed as not to alarm the civilian population or create excitement or demonstrations which might lead the Japanese consul general and spies in Honolulu to interpret them as a genuine Pearl Harbor alert against a possible Japanese attack and report this to Tokyo. The latter could send such information on to Admiral Nagumo in command of the task force enroute to Pearl Harbor, which on the 27th was still not too far from its point of departure in the Kurile Islands. Nagumo was jittery enough about the venture as it was without any suspicion that Hawaii was already getting ready for an attack. It was this unusual combination of insistent directives and qualifying restrictions in the Washington messages to Short which led the Army Pearl Harbor Board, when investigating the responsibility for the surprise attack, somewhat cynically to designate the Marshall message of the 27th to Short as the “do-and-don’t message.”

But more important than the above comments on the so-called warning messages to Short on the 27th and 28th is this crucial observation: If the men who wrote or approved these messages to Short really suspected any probability of an immediate Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and then ordered Short to go on an alert against local sabotage, they would have had to be nothing short of military idiots or political traitors, which would scarcely be true of Stimson, Generals Marshall, Gerow, Bryden, Miles, Arnold and Adams, and Colonel Bundy, or of Admirals Stark and Turner.

Concentration on local sabotage and civilian responses constituted a complete reversal of the attitudes and operations which would have been required to prepare for a possible enemy attack by warships and airplane bombers. Local sabotage turned attention inward and groundwise rather than outward and upward from which an air attack by Japan would take place—local sabotage in Honolulu from the air was very unlikely. An attack by Japan, and there were no other possible assailants, would come from the outside and the air.

Exclusive devotion to suppressing local sabotage also demanded operations which would be militarily suicidal, such as bunching the planes in a circle, wing to wing, where they could be more easily guarded and protected, but would be helpless in the event of a surprise air attack, as proved to be the case when the Japanese struck on the early morning of December 7th. Experienced military officers like Marshall, Gerow, Bryden, Miles, Arnold, Adams, and Bundy were very well aware of this.

Suppressing local sabotage without alarming civilians also encouraged giving very restricted attention to checking and preparing anti-aircraft protection. Concentrating on local civilian activities also naturally shifted emphasis away from detecting any possible approaching enemy task forces. Further, the special and repealed directions to avoid arousing civilian curiosity or excitement precluded any serious military operations, even increased reconnaissance, that would have been involved in getting ready for an attack by aircraft. It would have been impossible even to carry out an alert involving artillery operations without causing great excitement in Honolulu. Some of the heavy coast artillery was located right in the center of the city, and live ammunition had to be taken from magazines and placed by the guns. Fort de Russey was situated close to Waikai Beach and the most important hotel in the city.

Hence, it can safely be maintained that, if Washington had desired to tell Short indirectly and obliquely, but very clearly and obviously that the top military “brass” at Washington apparently did not expect in any immediate period a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, they could hardly have done better than the messages sent to Short on November 27th and 28th. They were a masterly achievement in the way of producing a “war warning” that did not warn against war, at least at Hawaii. The Washington brass knew that these were no actual war warnings, but some of the authors or advisers, notably Admiral Turner, acted, even before the attack, as though they thought they were. When Short was caught off guard by the surprise attack, the men who fashioned and sent these fake warning messages tried to pass them off as genuine and adequate warnings, and so have their defenders among publicists, historians, and journalists over the last quarter of a century.

The question naturally arises as to whether Roosevelt, Stimson, Marshall, Bryden, Gerow, Miles, Adams, Bundy, Arnold, Stark, Turner, and Ingersoll, in reality meaning Roosevelt, Stimson, and Marshall, deliberately intended the fake “warnings” to deceive Short end give him additional assurance that there was no probability of an attack on Pearl Harbor in order to insure that he would take no action which might frighten Admiral Nagumo and lead him to turn back with the task force that Yamamoto was sending to Pearl Harbor. Many of the more critical students of the Pearl Harbor episode have contended that the warnings to Short were actually intended to be misleading, and good arguments can be produced to support this interpretation, notably in the case of Stimson.

At this time (November 26-27), it appears that Roosevelt and most of the top military brass in Washington may have been pretty well convinced that, if Japan struck at all, it would probably do so at the outset in the southwest Pacific. Apparently, it was not before the afternoon or evening of December 3rd, at the earliest, that Roosevelt became finally convinced in his own mind or actually learned that the Japanese were planning to strike at Pearl Harbor on or about the 7th, confided this to Marshall and Arnold on the 4th, and immediately bottled up all possible warnings to Short and Kimmel by making it necessary to clear them through Marshall, who would certainly not forward any such warnings in violation of Roosevelt’s wishes and orders. Even on the 4th, as will be shown later on, while Roosevelt may have been convinced that the Japanese were on their way to attack Pearl Harbor, he was still waiting anxiously for an attack on one of the “three small vessels” that he had ordered sent out from the Philippines to draw Japanese fire, thus being able to start war after an attack and yet in time to save Pearl Harbor.

It was not until after the attack and the bad planners and bad guessers had been exposed that the attempt got underway to make Short and Kimmel the scapegoats for the surprise attack and try to interpret the fake warnings to them on the 27th and 28th as definitive and adequate warnings of an approaching Japanese attack. This malicious mendacity reached its most contemptible and despicable depths in some of the post-Pearl Harbor investigations, beginning with the kangaroo court of the Roberts Commission, thus creating what has been well designated as the “American Dreyfus Case.”

We now come to the alleged “warning” sent to Kimmel by Stark on the 27th. It has already been pointed out that Kimmel had casual but friendly relations with Roosevelt for a quarter of a century before he assumed command at Pearl Harbor, and was a close personal friend of Stark. Hence, he was justified in expecting a fair deal from Washington. He was told by Stark that he would promptly receive all the relevant information concerning any threats to Pearl Harbor and he had every reason to expect that he would get them. He did not. He did not receive any of the diplomatic intercepts in Purple after the Argentia meeting at Newfoundland in early August, 1941. He did not even get the Bomb Plot messages in J-19 and PA-K2 that were intercepted by MS5 from September 24th onward right at Fort Shafter. The fact that, before the Argentia meeting, Kimmel did obtain some of the contents of a few of the Japanese diplomatic messages from the Purple code, although there had been no mention of Purple or Magic in them, actually deceived him. This made him believe that he was getting all that came in after that time, whereas he received none.

Stark wrote Kimmel frequently and in a friendly manner but the main theme of his letters before September was that Germany was our main enemy, that Roosevelt wished to get into the war directly in Europe, and that the administration did not desire to be drawn into waging a two-front conflict by having a war with Japan on its hands. When Stark did begin later on to write Kimmel about a possible war with Japan, he stressed the fact that it would probably begin thousands of miles away in the Philippines, the southwest Pacific, or in the English possessions and the Dutch East Indies, and even here was as likely to be one of Japan against Britain and Holland as directly against the United States. Of course, Stark was fully aware that any Japanese attack on British or Dutch territory would immediately bring the United States into war against Japan, as arranged in ABCD and Rainbow 5. Never once did Stark hint of any early Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and it is very possible that he did not expect one until December 4th, when Roosevelt by his order to Marshall bottled up any Navy warnings to Pearl Harbor and Stark was so informed.

The actions of the Washington authorities which related to Kimmel’s and Bloch’s operations at Pearl Harbor supplemented Stark’s letters in giving Kimmel a definite impression that no attack on Pearl Harbor was expected by Washington. When Kimmel took over the command of the Pacific fleet in February, 1941, the Japanese Navy was, in Kimmel’s own words, superior to our Pacific fleet “in every category of fighting ships.” Nevertheless, in April and May, 1941, Kimmel was ordered to send about a fourth of his fighting force to the Atlantic to engage in what was described to him by Washington as the “first echelon of the battle of the Atlantic”—surely an unwise act if Washington was expecting to get involved in a prior war with Japan.

This early impression was reinforced by the failure of Washington to send Short and Bloch the additional planes they needed and requested if they were to maintain effective reconnaissance around the Hawaiian area and repel any Japanese air attack. Knox had indicated the need of more planes for Pearl Harbor in January, 1941, and Bloch had requested one hundred additional patrol planes, but not one had been sent before December 7th, 1941. Only six usable B-17 flying fortresses had been sent to Short before Pearl Harbor, although he had been officially allocated one hundred and eighty. Planes of all types were being shipped to Europe, especially to Britain and Russia, and B-17’s were being ferried to the Philippines and the Far East to bolster the defense there.

Furthermore, it is essential once more to recall Kimmel’s assignment and role as commander of the Pacific fleet. While he was in supreme command of all naval vessels stationed at Hawaii, the actual naval defense of Pearl Harbor was vested in Admiral Bloch, commander of the Hawaiian Coastal Frontier—the Fourteenth Naval District. To be sure, Bloch consulted with Kimmel and took orders from him when necessary, but Bloch and Short were responsible for protecting Pearl Harbor, and even here the main responsibility was that of Short and the Army. Kimmel’s function was to train personnel, provide and improve equipment, recondition ships, and, when so directed, to send them westward to Wake and Midway, and even to the Far East to raid the Japanese islands if war broke out between the United States and Japan. By assignment, duties, and activities, his role was offensive and oriented toward the mid-Pacific and the Far East, in accordance with the naval phases of Rainbow 5, based on the ABCD agreement.

We are now in a position to examine the so-called war-warning to Kimmel that he received from Stark on November 27th. To get a better idea of what was on the mind of Stark and his associates in Washington at this moment, we may note that Kimmel had received a dispatch from Stark on the 24th which included the following statement: “Chances of favorable outcome of negotiations with Japan very doubtful. This situation coupled with statements of Japanese Government and movements of their Naval and Military forces indicate that in our opinion that a surprise aggressive movement in any direction including an attack on the Philippines or Guam is a possibility.” On the next day, Stark wrote a letter to Kimmel. Although Kimmel did not receive it until December 3rd, it reveals the trend of Stark’s thinking on the 25th. He stated that a Japanese attack on the Philippines would be the most embarrassing thing that could happen to the United States and that some Washington authorities thought that this might occur. Stark went on to say that he, personally, was inclined to “look for an advance into Thailand, Indo-China, Burma Road area as the most likely.” Stark concluded by stating that: “Of what the United States may do, I’ll be damned if I know. I wish I did. The only thing that I do know is that we may do almost anything.” This well illustrates Stark’s frequent personal confusion and uncertainty.

One may observe that the “almost anything” did not include an attack on Pearl Harbor, despite Stark’s knowledge of the Bomb Plot messages from the time of the decoding and translation of the first one on October 9th. By the 24th and 25th of November, his thinking appeared to be almost entirely dominated by the thought that the Japanese would first attack in the Far East, indeed in the furthest East.

Kimmel, of course, knew nothing about the negotiations with the Japanese or the details of the Japanese movements which had led Stark to these conclusions. He did not even know that Hull had sent an ultimatum to Japan on November 26th, which Washington expected would lead to war with the United States in a few days—when the Japanese sent their reply to Hull. On November 27th, Kimmel received from Stark the following so-called “war warning” message, which has been represented by Roosevelt’s defenders as sufficient to alert Kimmel as to the possibility of an imminent Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, although this was not even mentioned by implication:

This despatch is to be considered a war warning. Negotiations with Japan looking toward stabilization of conditions in the Pacific have ceased and an aggressive move by Japan is expected in the next few days. The number and equipment of Japanese troops and the organization of naval task forces indicate an amphibious expedition against either the Philippines, Thai, or Kra peninsula, or possibly Borneo. Execute an appropriate defensive deployment preparatory to carrying out the tasks assigned in WPL 46. Inform District and Army authorities. A similar warning is being sent by War Department. SPENAVO inform British Continental Districts Guam Samoa directed take appropriate measures against sabotage.

Not only the content of Stark’s “war warning” message but also the method used in transmitting it further emphasized to Kimmel that Stark and Washington were concentrating on the threat of Japanese movements in the Far East. Just as the message sent to Short on the 27th was drafted with MacArthur primarily in the mind of Washington authorities, so Stark’s message to Kimmel clearly indicated that Washington framed it primarily for Admiral Hart, Commander of the Asiatic fleet in the Far East. This Navy “war warning” message was addressed as follows:

For Action: Cincaf (Hart), Cincpac (Kimmel).

For Info: Cinclant (King, USN, Ghormley, London) Spenavo (Creighton, Singapore) . . .

It would, of course, be quibbling to contend that Kimmel did not know that the message was designed for him as well as for Hart. But it is also a fact that, as shown by the prior listing of the lower ranked Hart, that it was the latter whom the drafters had primarily in mind. Admiral Ingersoll actually testified that the warning of the 27th was intended primarily for Hart. It is equally true that Kimmel noted this order of address and naturally interpreted it as deliberately intended to emphasize that Washington believed that the real danger from Japan lay in the Far East. With never one mention of a threat to Hawaii, Stark’s message diverted attention to the Far East. Nevertheless, Kimmel faithfully carried out the directions in this message of the 27th, as well as in the supplementary messages from Stark, just as though he had been the sole addressee in the “war warning” message. Stark testified on the witness stand that Kimmel had done all that was required of him in the message of the 27th.

Stark’s statement started off with the assertion that “This dispatch is to be considered as a war warning.” This carried a much weaker and more generalized connotation than, “This is a war warning.” It went on to state that negotiations with Japan, of which Kimmel knew no details, had ceased and aggressive action by Japan might be expected within the next few days. All known Japanese equipment and activities indicated an “amphibious expedition against the Philippines, Thai or Kra Peninsula, or possibly Borneo.” Kimmel was ordered to “execute an appropriate defensive deployment preparatory to carrying out the tasks assigned in WPL 46” if war broke out.

Two later supplementary messages were sent to Kimmel by Stark on the 27th. One dealt with sending infantry divisions to defend adjacent bases in the Pacific. The other ordered, if Kimmel thought it feasible, sending Army patrol and pursuit planes to Wake and Midway on carriers then at Pearl Harbor. There was no suggestion of an extensive offensive deployment by the Pacific fleet to the Marshalls to restrain Japanese movement toward the Malay barrier. Commander Hiles has suggested that if the Stimson message to Short on the 27th was a “do-don’t message,” those of Stark to Kimmel on the 27th constituted “do nothing” messages, so far as preparing Hawaii for an attack on Pearl Harbor. On November 29th, Stark sent Kimmel another message directing him to take no action under WPL 46 until “Japan has committed an overt act,” thus matching the similar order sent to Short on the 27th.

Kimmel carried out these orders promptly. On November 28th, Admiral William F. Halsey was sent to Wake with the carrier Enterprise, three heavy cruisers and nine destroyers. On December 5th, Admiral John H. Newton was sent to Midway with the carrier Lexington, three heavy cruisers and five destroyers; and also on the 5th, Admiral Wilson Brown was sent to Johnson Island on a practice operation with some cruisers and destroyers, there being no remaining carrier for him. The carrier Saratoga had been sent to the Pacific coast for reconditioning and equipment with radar and was just starting to return to Pearl Harbor. It was fortunate that the carriers and heavy cruisers had been sent out of Pearl Harbor before the 7th; otherwise, the naval disaster from the surprise attack would have been far more serious. The battleships which were destroyed or injured were of very secondary importance in the type of naval warfare which ensued.

Of course, if Kimmel had been actually warned of imminent danger on the 27th, as he could and should have been, the battleships, carriers, and heavy cruisers at Pearl Harbor would all have been deployed and directed in such fashion as possibly to have detected, intercepted and surprised the Japanese task force under Nagumo and inflicted serious injury upon it, even though it was outnumbered by the Japanese in carrier and planes: that is, provided that the Japanese consul general and spies in Honolulu had not become alarmed by this desertion of Pearl Harbor, informed Tokyo, and the latter had not recalled Nagumo, which is probably what would have happened. Even if Nagumo had proceeded to Pearl Harbor, there is little probability that he would have sent his bombers to attack an empty naval base.

Kimmel ordered the planes that were taken on the carriers by Halsey and Newton to conduct reconnaissance sweeps to detect any possible enemy movements or threats. This was done promptly and on an extensive scale—about two million square miles of ocean area.

There was no valid reason why Kimmel should have regarded these messages that he received from Stark on the 27th and 29th as, in any sense, a warning that Japan might strike at Pearl Harbor within any immediate period. The first message received on the 27th was obliquely labelled a “war warning” but it meant nothing at all in this respect, when considered in connection with the remaining portion of the message and those that followed. Indeed, their total implications were quite to the contrary. “War warning” as used by Stark was only a formal label and a vague, convenient and routine semantic “catch-all,” as Kimmel has well described it. Since Kimmel had been denied any knowledge of Magic operations, was not sent a Purple machine, and was ignorant of diplomatic negotiations with Japan after the Argentia meeting in August, the statement that negotiations with Japan had ceased could not have meant anything specific or alarming to him.

He not only had no knowledge of the details of the negotiations revealed in the intercepted Japanese diplomatic messages that were kept from him after August but he was not informed of even such fundamental items as Hull’s having sent an ultimatum to Japan on November 26th. The only possible war mentioned was one that might start in the southwest Pacific, East Indies, or Philippines, some thousands of miles away, as the result of a possible Japanese amphibious expedition and attack, and no assurance was expressed by Stark that even this expedition would inevitably mean an attack on the United States unless it was made on the Philippines. All the orders or suggestions for action contained in the messages received by Kimmel on the 27th and 29th clearly indicated that Kimmel was to get ready for possible war in the Far East, and if feasible to send ships to Wake and Midway with planes and reinforcements. Only in the event of war in the Far East was he to make forays against the Marshalls, and try to draw Japanese strength away from the Malay barrier.

Just as the order to go on alert against local sabotage and concentrate attention on civilians in Honolulu and environs made Short believe that Washington had no suspicions of any imminent attack on Hawaii, so the measures Kimmel was directed to take, as laid down in the messages of the 27th and 29th, gave him the inevitable impression that Washington had no suspicion of any immediate Japanese action against Pearl Harbor. The Naval Court of Inquiry, which met from July to October, 1944, asserted that the so-called war warning message sent by Stark to Kimmel on November 27th “directed attention away from Pearl Harbor rather than toward it.”

The orders given to Kimmel also involved the further depletion of the already inadequate defensive personnel and equipment at Pearl Harbor—sending more sailors and soldiers to the mid-Pacific, along with robbing Pearl Harbor of pursuit and patrol planes, which were in almost fantastically short supply there, and sending all the carriers away. In the same way that ordering Short to go on alert against local sabotage convinced him that there was no fear in Washington of any attack on Hawaii, so the orders to Kimmel further to deplete his Pearl Harbor supplies, equipment and personnel were tantamount to telling him that Pearl Harbor was not in any danger of attack, so far as Washington was aware, on November 26th and 27th. He received no direct warnings of any probable attack there after that time.

One item that has been especially seized upon by defenders of Roosevelt to demonstrate that Kimmel was adequately informed of the threat of a Japanese air attack on Pearl Harbor is that he did receive the information that on December 1st and 2nd that Japan had ordered the destructions of its codes and code machines.

This contention will not hold up under the most elementary analysis. In the first place, Kimmel is expected to have reacted to this information as though he had been informed of everything that the Washington authorities knew by December 4th: the whole complex of Magic, the breaking of the Purple code in August, 1940, our reading of all Japanese diplomatic messages from that time to December, 1941, all the negotiations that had taken place since August, 1941, the deadlines set by Tojo in November, 1941, his statement of “the things that are automatically going to happen” if negotiations had not been settled by November 29th, Hull’s ultimatum of November 26th, which Washington was convinced the Japanese would reply to by a declaration of war, and the whole Winds set-up and its execution on December 4th. None of these vital facts, which gave the codes destruction orders their real significance and implications, were known to Kimmel. On the other hand, in Washington, the codes destruction orders were a dead giveaway as to imminent war when taken in the context of all the other vast array of intercepts and intelligence that was available there.

Despite all this, even at Washington the codes destruction orders were not taken as an infallible sign that Japan was going to make war, especially war on the United States. Even Commander Safford did not consider that the codes destruction orders meant certain war until Winds Execute was intercepted on December 4th. The latter did make it clear that Japan was going to make war and would start it against the United States and Great Britain, but not against Russia. This is precisely why Winds Execute was so vitally important in incriminating the Washington authorities and why it was frantically suppressed and so emphatically declared non-existent by those who sought to conceal their guilt after December 7th.

While Kimmel was informed of the Winds code and Commander Rochefort had experts monitoring on it, neither Kimmel nor Rochefort was told that Winds Execute had been intercepted by Washington on December 4th. Rochefort’s staff was unable to intercept it at Pearl Harbor because they were monitoring the voice circuit from Japan. Winds Execute actually came over the Japanese Morse code and Safford was lucky enough to pick it up at Cheltenham, Maryland, as indicated earlier.

Further, there is actual evidence that the codes destruction messages did not inevitably mean war in December, 1941. This news came to Washington on December 1st and 2nd. Nagumo was not ordered to climb Mount Niitaka until the 5th. If the United States had offered to resume negotiations on the 2nd, 3rd or 4th, his task force could have been called back and most probably would have been. It was so arranged in his orders. It is very possible that an American offer to resume negotiations as late as early on December 6th might have led to calling off the attack on Pearl Harbor, but Roosevelt, Hull and Stimson were determined that negotiations would not be resumed after Hull sent his ultimatum on November 26th. Its terms assured that they would not be.

Moreover, the routine destruction of codes was a not unusual occurrence, and had often taken place without an ensuing war. It can be only a casual or formal process. Kimmel had known that the Japanese consulate in Honolulu had frequently burned its papers, which might have been codes, for all that he knew. It is true that, when taken in their full context, as known by Washington, the Japanese code destruction orders of December 1st and 2nd were extreme and sweeping and very probably were a conclusive sign of war, but Kimmel knew nothing of this context. Along with this was the fact that all the information and so-called war warnings that Kimmel and Short received on November 27th, 28th and 29th distracted attention away from Hawaii and emphasized the Far East. Further, any appropriate action by Kimmel, if based on a full recognition of the meaning of the codes destruction order, would have required a complete alert which would have been wholly at variance with the orders to Short not to alarm the civilian population at Hawaii, and these orders to guard against local sabotage were not lifted prior to the Pearl Harbor attack, not even on the West Coast by General Arnold until December 6th at Sacramento. Stark’s message to Kimmel on the 29th had also ordered Kimmel not to take any sweeping offensive action under WPL 46 until after Japan had committed an overt act of war.

Hence, one can safely conclude that Kimmel’s having received the news of the Japanese code destruction orders of December 1st and 2nd was no more of a war warning that the Japanese might strike Pearl Harbor from the air almost immediately than were the messages received by him and Short on the 27th, 28th, and 29th.

In short, the “warnings” received by Kimmel on the 27th and 29th hardly went much further as to details or the imminence of war than Admiral Stark’s release to his Admirals after the Singapore Conference of April, 1941, and the formulation of Rainbow 5, to the effect that the question of the United States entering the war was no longer one of whether but of when and where.

Short and Kimmel have been vigorously criticized on the ground that, in the light of the traditional strategic assumptions about naval warfare in the Pacific, they did not, on their own knowledge and initiative, recognize the probability that, in the event of war, the Japanese would first attempt a surprise attack on the American Pacific fleet, wherever it was stationed, even though top authorities in Washington seemed to overlook this. As a matter of fact, they never lost sight of this possibility at any time; indeed, they seemed far more aware of it than Stimson, Marshall, or Stark. Knox had stressed this possibility in January, 1941.

From the time Kimmel assumed command at Pearl Harbor in February, 1941, both he and Short had frequently mentioned and discussed the possibility of a surprise Japanese attack there, and recognized the action and supplies needed to detect and turn back such an attack. They had vainly requested the equipment required effectively to carry out such a protective policy, especially the planes necessary to carry out adequate and continued reconnaissance and to destroy or cripple any Japanese task force approaching Pearl Harbor, but they had received virtually nothing down to the Pearl Harbor attack. As noted earlier, on April 9, 1941, General Frederick L. Martin and Admiral Patrick N. L. Bellinger, commanders of the Army and Navy air forces in Hawaii, handed in a report about the feasibility and danger of a Japanese surprise air attack on Pearl Harbor that was virtually identical to the plan Yamamoto actually carried out under Admiral Nagumo’s command. It was carefully studied by Short and Kimmel and was forwarded to Marshall in Washington on April 14th but without any response directing appropriate defensive operations at Pearl Harbor or supplying adequate equipment.

Early in 1941, Admiral Bloch had asked for one hundred additional patrol planes that would be needed for effective reconnaissance, and Short had requested 130 B-17 bombers needed for both reconnaissance and attacking an approaching Japanese task force. These planes were promised but never delivered. None of the hundred was ever sent to Admiral Bloch for naval reconnaissance at Pearl Harbor, and a scant twelve B-17 bombers were sent to Short, only six of which were suitable for use after they arrived. Planes needed by Short and Kimmel at Pearl Harbor had been diverted to the Atlantic and Europe to aid Britain and Russia, along with one-fourth of Kimmel’s naval force, sent there in April and May, 1941. Other planes were belatedly sent to the Philippines and to China.

Throughout 1941, Short and Kimmel were actually far more alert and apprehensive to the danger of a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in the event of war with Japan than was Washington, even though they had been denied the Bomb Plot messages. They were simply refused the equipment required to meet and allay their apprehensions in this matter. Nevertheless, despite the blackout of Pearl Harbor, the patrol planes at Pearl Harbor carried out limited reconnaissance and the planes on the task forces sent out under Admirals Halsey and Newton did conduct extensive reconnaissance in the days just before Pearl Harbor in the effort to detect any evidence of a Japanese task force moving against Pearl Harbor, covering no less than two million square miles of the surface of the Pacific.

In conclusion, it is abundantly clear that Short and Kimmel were not adequately informed, or literally even warned at all, about the prospect of an imminent Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. What were later dishonestly described as warnings by defenders of Roosevelt actually confirmed and intensified their impression that Pearl Harbor was not in any immediate danger of a surprise attack. This almost criminal failure to warn Short and Kimmel was fully realized in Washington in late November and early December, 1941, by such outstanding operating experts as Colonel Otis K. Sadtler, acting chief of the Army Signal Corps, Colonel Rufus S. Bratton, chief of the Far East Section of Naval Intelligence, and Commander Arthur N. McCollum, chief of the Far East Section of Naval Intelligence.

These men sought to have Short and Kimmel directly and adequately warned, only to have their efforts ignored or frustrated. McCollum believed that Kimmel should have a better warning on the 27th of November. He was probably the best informed person in Washington at the time on the situation in the Pacific, and he prepared a general survey and evaluation of the state of affairs in the Pacific area, suggesting what should be done, and showed this to Turner, Noyes, and Wilkinson, but it got no further. It would have been invaluable to Kimmel, and if sent to Pearl Harbor would doubtless have led to preparations that would have frustrated Yamamoto’s plan to carry through the task-force attack. McCollum then prepared a precise warning to Kimmel on December 1st and another on the 4th, but neither was sent. They were killed by Stark and Turner, which in this case meant Turner, who stubbornly contended that the “warnings” sent on November 27th provided all necessary information to put the Hawaiian commanders on the alert. When McCollum, along with Admiral Noyes and Captain Wilkinson, suggested to Stark on the morning of the 7th that he warn Kimmel at once, both were ignored.

No honest and competent Intelligence, Signal Corps, or Naval Communications officer who was in Washington in November and December, 1941, has ever contended, at least not prior to being intimidated during the post-Pearl Harbor investigations, that Short and Kimmel were clearly and adequately warned of any probable impending attack on Pearl Harbor, despite the increasing abundance of material available in Washington from early October onward to justify and validate such a warning and make it mandatory.

There is no substantial evidence whatever that either Short and Kimmel failed in their duties in any way whatever at Pearl Harbor or were in any manner responsible for not anticipating and repelling the arrival of the Japanese task force that made the attack on the morning of December 7, 1941. They did not have divine wisdom or insight, but it is very doubtful if two men better fitted or more competent for the posts they were occupying in 1941, or officers more diligent in executing their duties, could have been found in the United States. They were clearly more competent, energetic and alert with respect to all matters connected with their assigned duties at Pearl Harbor than their superior officers, General Marshall and Admiral Stark, were in Washington.

The allegation of Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal, backed up by Admiral Ernest J. King, after the Hewitt Inquiry, that Kimmel failed to demonstrate the superior judgment necessary for exercising command commensurate with his rank and assigned duties, and the order that Forrestal then issued that Kimmel should never again hold any position in the United States Navy which required the exercise of such superior judgment, was one of the most unfair, malicious, and mendacious statements ever made by prominent American public figures in their official capacity. It flew directly in the face of the conclusions of the Naval Court of Inquiry. The criticisms of General Short in the post-Pearl Harbor investigations were equally biased and unfounded and were completely refuted.

Since substantially the same “warning” message that was sent to General Short on the 27th was also sent to General MacArthur in the Philippines at the same time, it is instructive to point out significant differences in the message sent to the latter. These variations all stem primarily from the fact that there was little to hide from MacArthur and Hart. Both Washington and Manila knew that war with Japan was coming soon and that the Philippines were almost certain to be attacked soon after it started. Hence, MacArthur and Hart were left free to take all measures they deemed essential to get ready for the blow. The only exception was that Japan must be allowed to fire the first shot. MacArthur and Hart expected that the Japanese would attack Pearl Harbor before they struck the Philippines because they needed to destroy the Pacific fleet and protect their flank before they could safely carry on extensive campaigns in the Far East and the southwest Pacific.

There was nothing in the message to MacArthur relative to refraining from alarming the civilian population; nothing forbidding the disclosure of intent; and nothing restricting the dissemination of the “highly secret information to minimum essential officers.” Manila was to operate under a “Revised Rainbow 5,” which had been brought out to MacArthur personally by General Brereton. There was no reference to any “Revised Rainbow 5” in the message to Short or any indication that he knew of any such revision. Finally, MacArthur was directed to inform Hart of the contents of the November 27th message, while no suggestion was made to Short that he notify Kimmel. As Commander Hiles characterizes the situation:

The conclusion seems obvious and incontestable. The Far East Commands at Manila were given a free hand with no special admonitions or restrictions whereas the Hawaiian Commands were handcuffed and hogtied. It required some finagling to do the trick and fit it nicely into a pattern of intrigue and deceit in such fashion as to appear plausible for the record. To devise and express in words a war warning that is not a war warning calls for some nice mental gymnastics, but it was done and it worked, even though it involved the cooperation of a considerable number of the highest functionaries of the government and no end of conferences, memoranda, and the like.

It is interesting and illuminating to know that while MacArthur and Hart were favored in the above manner by Washington, they did not really need such special concern. They were far more fortunate in having a Purple machine at Manila and were also assisted by a special arrangement unique in all pre-Pearl Harbor communications connected with Japanese-American relations and any probable Japanese attack on American forces or territory.

When MacArthur felt the need of being well informed as to the diplomatic situation between the United States and Japan, he requested that he be sent one of the best experts from the Army Signal Corps in Washington, and specified Colonel Spencer Akin as the man he desired. Colonel Akin had access to Magic and was fully aware that neither Manila nor Fort Shafter had been fully informed of the increasingly tense situation in Japanese-American relations. He was especially concerned over the failure to send the Bomb Plot messages to Hawaii. Hence, Akin arranged with Colonel Otis K. Sadtler, acting head of the Signal Corps in Washington, that Sadtler would send him such information as would be required to keep MacArthur fully informed of the increasingly alarming developments. Akin was shrewd and foresighted enough to insist on being promoted to Brigadier General before he would consent to accepting MacArthur’s request to come to Manila. Sadtler worked just as honestly and patriotically but lived and died a colonel.

Sadtler sent Akin all the information he thought necessary to keep MacArthur fully informed as to the likely time and place of any Japanese attack, whereas Short did not receive any Purple, J-19 or PA-K2 messages after the end of July. A specially important item in the information sent over this secret Sadtler-Akin pipeline were the Bomb Plot messages being intercepted at MS5 at Fort Shafter and other monitoring stations in the United States and forwarded to Washington to be decoded, translated, read, filed away and kept from Short.

Hence, MacArthur had been adequately informed of the imminence of war with Japan before he received the Marshall message of the 27th. He did not need it, but he was able to read far more into it than could Short, who had been kept completely in the dark about the ominous developments during November, 1941. MacArthur was ready for the attack and had cleared his beaches in anticipation of the approaching Japanese assault that he expected to take place immediately after an attack on Pearl Harbor.

One of the main myths circulated by the “blackout” and “blurout” historians is that MacArthur was actually surprised by the Japanese, even six hours after he had learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and that his airplanes had remained huddled helplessly on the ground and were destroyed by the Japanese bombers as Short’s had been that morning at Hawaii. They had actually been in the air on reconnaissance during the morning of the 7th, and had just returned to refuel when the Japanese attack came, quite unexpectedly at the moment. It had been doubted that the Japanese bombers could fly from Formosa to Manila and return, and weather conditions were also such that it seemed unlikely that they would even make the attempt on the 7th.

MacArthur and Akin knew that Short was being deprived of this alarming information that they received from Sadtler in Washington, but had to sit quietly by and await a Japanese attack. They did not dare pass on this crucial information to Short because any resulting precautionary action on the part of Short might reveal the existence of the Sadtler Akin pipeline and lead to its suppression, which would have been a serious loss for Manila.

Commander Laurance F. Safford, chief of the Security Section of Naval Communications in Washington, thought at the time that all such disturbing information was being sent from Washington to Admiral Bloch at Pearl Harbor. Hence, he made no attempt to set up a secret Safford-Rochefort pipeline which would have given Commander Rochefort, chief of Naval Communications Intelligence at Pearl Harbor, essentially the same information that Sadtler was sending Akin. Rochefort has told me several times that if this had been done, Pearl Harbor would have gone on alert long before Nagumo approached Pearl Harbor, in all probability before he left the Kurile Islands.

Rochefort has criticized Safford for even failing to give him some clear hints of the dangerous developments in Japanese-American relations after November 26th, or even earlier, since they were close friends and in constant communication. Even a few allusions about the actual situation would have led Rochefort to intensify precautionary monitoring action. He could not decode Purple, for Pearl Harbor had no Purple machine, but he could have decoded and read messages sent in J-19 and PA-K2, many of which, notably the Bomb Plot messages, indicated a serious threat to Pearl Harbor.

Safford asserts that he supplied Rochefort with the changing keys for these codes but did not feel that it was necessary to suggest that Rochefort use them for intercepting and reading the Japanese diplomatic messages because he thought that Kimmel and Bloch were getting all the relevant information from their superior officers in Washington. He remained misled about this for nearly two years after the Pearl Harbor attack, when he first discovered that Bloch and Kimmel had not been sent the relevant information on Japanese-American relations at any time before the attack. Until then, he had believed that Kimmel had actually been seriously derelict in not heeding his warnings and executing his duties. Safford made this discovery when he was examining the Navy files and found that the incriminating documents relative to Pearl Harbor had been removed. Fortunately, he found where they had been hidden before they could be destroyed and restored them to the files. Later on, this enabled the Army Intelligence officers to discover that most of the incriminating documents had been removed from the Army files and not replaced.