AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

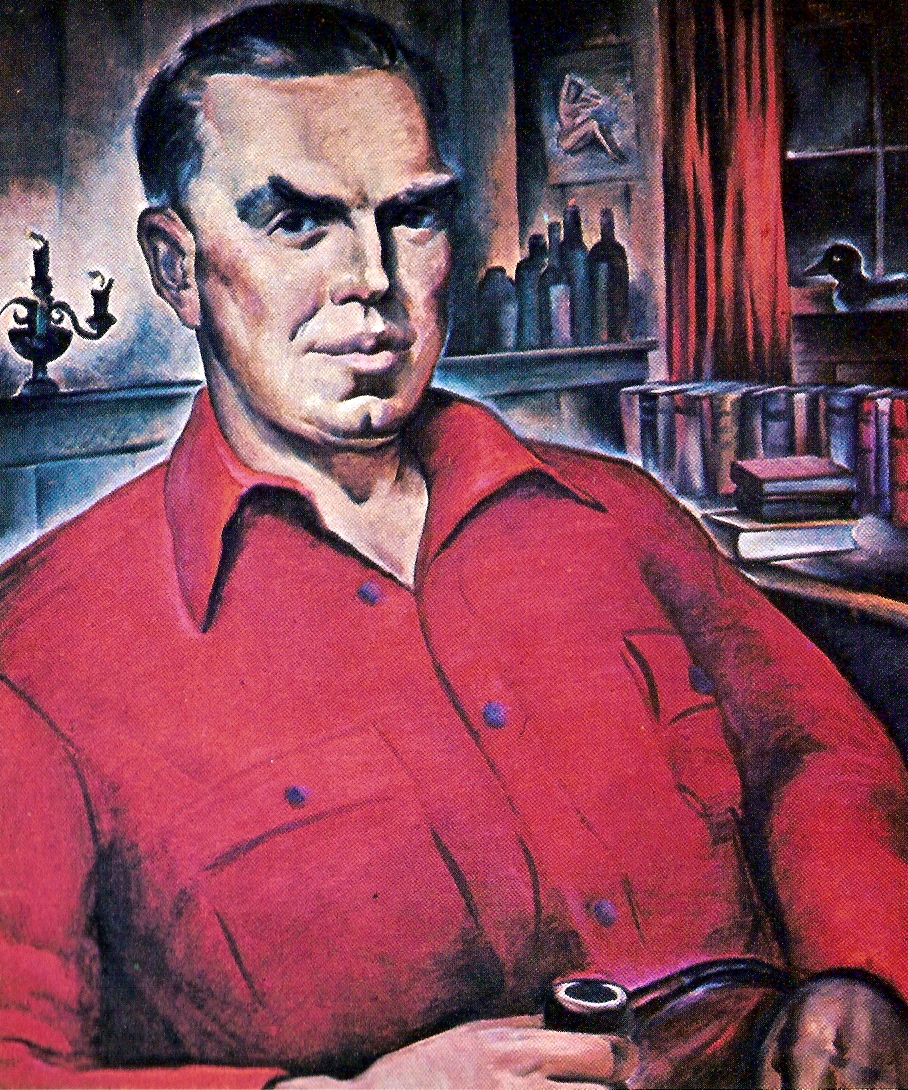

Oil portrait

by Virginia True

Pearl Harbor after a Quarter of a Century

Harry Elmer Barnes

VI: The Blackout of Hawaii on the Eve of Pearl Harbor

In the confession of the Russian spy in Tokyo, Richard Sorge, he stated that in October, 1941, he had informed Stalin that the Japanese intended to attack Pearl Harbor within sixty days. Stalin may well have passed this on to Roosevelt in return for Sumner Welles’ helpful gesture in informing him of Hitler’s plan to attack Russia. One of the last things that Stalin would have wished to have happen at this time in the Far East was the destruction of the American Pacific fleet. . . . [A] very prominent American Army Intelligence officer in service in the Far East during 1941, whose name I am not yet free to mention, had gained knowledge of the Yamamoto plan to send a task force to attack Pearl Harbor and sent three separate messages to Washington revealing this information, and at least two of these reached the Army files well before the attack on Pearl Harbor.”

—Harry Elmer Barnes

We may now deal with the problem of why, how and by whom Short and Kimmel were, during the more than a week before the Pearl Harbor attack, deprived of the large and varied mass of information that had been accumulated in Washington and demonstrated, surely by October, 1941, that war with Japan was now definitely in the making, that by November 27, 1941 it might start at any time, but most likely when Japan submitted its reply to Hull’s ultimatum of November 26th, that by December 1st and 2nd it was at hand, that by December 4th Japan would declare war against the United States and Great Britain, that by the early afternoon of the 6th war could come at any moment, and that by the morning of the 7th the Japanese would in all probability attack Pearl Harbor about 1:00 P.M. Washington time, or 7:30 A.M. Pearl Harbor time. This leaves out of consideration the Kita message, which had been processed by 2:30 on the afternoon of the 6th and definitely indicated that the Japanese would arrive off Hawaii by the evening of the 6th and be prepared to attack Pearl Harbor on the morning of the 7th.

The blacking out of Short and Kimmel relative to the Japanese threat at Pearl Harbor is a highly complicated situation involving many facts, issues and changes of policy and operations, especially during the year 1941. The only consistent item and unvarying policy in all the tortuous maze of developments from October 5th, 1937, to the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor was the determination of Roosevelt from the autumn of 1939 to put the United States into the war, but his conception of the enemy to be fought at the onset of war changed markedly throughout this period. At the outset, it was Japan, as revealed by his suggestion at the first Cabinet meeting, the largely secret strengthening of the American navy, the Chicago Bridge speech of October 5, 1937, and Captain Ingersoll’s mission to Britain in the winter of 1937-1938. After the outbreak of war in Europe in September, 1939, it became Germany, where Churchill was exerting his main pressure for collaboration. It was not until this seemed almost impossible to accomplish by mid-summer of 1941, because Hitler provided no casus belli, that Roosevelt finally decided that he would have to enter war through the back door of Japan.

No other prominent American official except Stimson was clearly determined to support war with Japan at this time. Stimson first became publicly very influential in this policy only by the summer of 1941 when Roosevelt decided that Japan would probably have to become the main initial target of his bellicosity. After this date Stimson, already appointed Secretary of War in June, 1940, logically became the most undeviating member of Roosevelt’s entourage so far as upholding the war motif with Japan was involved.

There are a number of relevant questions which have to be raised, some of which have not been entirely resolved even today and may never be wholly cleared up. The first one is how and why many of the top military officials in both the Army and Navy at least appeared to ignore at the most crucial period, November and December, 1941, the basic Japanese strategy of a Pacific war—an initial attack on the American Pacific fleet—which had been demonstrated to be sound and practical and had been given special relevance after the Pacific fleet had been based at Pearl Harbor in the spring of 1940? How could they have disregarded the numerous Bomb Plot messages and the Martin-Bellinger Report, both of which clearly pinpointed Pearl Harbor as the inevitable target of any Japanese air attack if war came?

How could this top military personnel appear to be unaware of the special threat to Pearl Harbor when all the operating groups in the lower echelons, who were devoted to matters of Magic and intelligence, were discovering and emphasizing this danger and were persistently seeking to get this evidence presented to their superiors and have Short and Kimmel properly warned while there was still an abundance of time in which to alert Hawaii and avert an attack there? Why did the most concerted effort to blackout Hawaii begin when Roosevelt’s shift of policy to direct bellicosity toward Japan obviously increased the danger of an attack there? Short was blacked out as to negotiations with Japan after the latter part of July and Kimmel after the Argentia meeting in August.

How were the top military echelons able to keep the impressive evidence of danger to Hawaii suppressed? Were they ordered by Roosevelt to suppress this material and withhold it from Hawaii? If so, how many were so ordered, and who were those who suppressed the evidence without any order to do so? Why, when the threat to Hawaii became more clear and evident, did most of the top military echelons turn their attention to the Far East and apparently neglect Hawaii?

Who in the upper civil and military echelons in Washington wanted the United States to go to war, and if they did, was it to be war against Germany or Japan? Neither Marshall nor Stark really wanted any kind of war at the moment, with either Germany or Japan, because they believed that this country needed to get better prepared to wage a world war; they were especially opposed to war with Japan in 1941. Hull was apparently satisfied to continue feeding his banalities and platitudes to Nomura and assuring the probability that no peaceful settlement could be made with Japan. He hated both the Germans and the Japanese and, as an old Tennessee feudist, was hardly opposed to a little killing on principle, but he was surely not a leading protagonist of open hostilities although he knew that they would almost surely result from his operations as Secretary of State.

Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, as one of the leading warmongers of the time, was eager to get us into any available war, although he preferred one with Germany, but he wished to have Hawaii well prepared for war and seems to have played no decisive role in precipitating war with Japan or blacking out Hawaii. By the latter part of November, when the Japanese began to send extensive forces southward and it seemed possible that the Japanese would make their first attack in the southwest Pacific, on the islands or mainland, Knox was especially vigorous in maintaining that the United States must stick by the arrangements in ABCD and Rainbow 5 and resist the Japanese by force even though there was no attack on American territory and forces.

When I was teaching at the University of Colorado in 1949, one of my mature students was a nephew of Knox. Learning of my interest in Pearl Harbor, he brought up the subject of Knox in relation to this question. He said that the Knox family had always believed that the Secretary’s death was hastened by his sense of shame and humiliation over what he had discovered to be the deliberate failure of Washington to warn Short and Kimmel about the coming surprise attack, and the subsequent attempt to make Short and Kimmel the scapegoats for the quasi-criminal neglect by the guilty parties.

Since Knox died on April 28, 1944, he did not live to learn the revelations brought forth in most of the post-Pearl Harbor investigations, but the Naval Intelligence and Communications experts of 1941 knew and resented the failure to warn Short and Kimmel, and Knox may have called them in for questioning. Indeed, all he would have needed to do was to talk to his friend, the distinguished Admiral William H. Standley, about the “kangaroo court” conducted by Justice Owen Roberts, where this disgraceful smearing of Short and Kimmel, especially the latter, got off to a running start. A similar impression was given to me by Admiral Ben Morreell, who was closely associated with Knox and travelled thousands of miles with him between Pearl Harbor and Knox’s death. He assured me that Knox was “clean as a hound’s tooth” with respect to any complicity in blacking out Pearl Harbor in December, 1941, and became increasingly suspicious of Roosevelt’s role in this matter.

Only Stimson, who had been brought into the Cabinet in June, 1940, clearly stood with Roosevelt in strongly favoring war with both Germany and Japan. He had been one of the leaders in the interventionist group in the East from 1937 onward who had urged our entering the European war; but he had also been the outstanding Japanophobe among the top civilian figures in the United States for a decade. How were Roosevelt and Stimson able to steer the country into war in the face of the great strength of non-interventionist sentiment in the country at large?

The year 1941 brought all these confused policies and personal attitudes to a head, partly due to new international developments and partly as a result of the unexpected responses of leading personalities involved, notably Hitler. Although keeping Japan as a martial ace-in-the-hole, Roosevelt started out the year with his interventionist policy mainly centered on Germany, an attitude which was supplemented by strong pressure from Churchill. Hitler was to be provoked into starting war by challenging American unneutral action in convoying supplies to Britain and Russia on the Atlantic, but Hitler refused to rise to the bait as he had earlier declined to do in the case of the Destroyer Deal of 1940 with Britain and the lavish shipment of arms to Britain. By the end of June, 1941, the prospect of provoking Hitler had greatly dimmed and it seemed likely that the most effective way in which to get into the war was to incite Japan to take some action which would inevitably mean war. At this moment, Roosevelt, most appropriately, brought Secretary Stimson into direct action to implement the Japanese policy that he had “sold” to Roosevelt with great ease on January 9, 1933.

Although there is no doubt that after September, 1939, Roosevelt definitely preferred to get into the war directly in Europe, he had always kept Japan as an ace in his sleeve ever since his meeting with Stimson in January, 1933, and the first meeting of his Cabinet in March, 1933, as we have been told by then Postmaster-General James A. Farley. He had secretly built up the American navy, and our only likely naval enemy was Japan. His Quarantine Speech in Chicago in October, 1937, straight Stimson doctrine, emphasized Japan more than Germany. In the winter of 1937-1938, he sent Captain Royall E. Ingersoll to Europe to consider possible American operations with the British in the event that they became involved in a war with Japan. Roosevelt early adopted measures aiding the Chinese in their war with Japan, and there is much evidence that the financial and diplomatic policies of the United States played a very considerable role in bringing about the renewal of war between Japan and China in July, 1937.

The outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 only provided a temporary interlude which distracted Roosevelt from his underlying aggressive program relative to Japan. The Roosevelt-Stimson policies and actions with reference to Japan after June, 1941, that led to the outbreak of war on December 7, 1941, were summarized early in this article and need not be repeated here.

Much has been written on the possible communist influence on Roosevelt’s decision to make war on Japan, but even revisionist historians have concentrated mainly on that exerted by Chiang kai-Shek and Owen Lattimore through pro-communist officials among Roosevelt’s associates at the White House, such as Lauchlin Currie and Alger Hiss, in leading Hull to kick over the modus vivendi and send his ultimatum to Japan on November 26, 1941. It was a far more complicated and far-reaching operation than this, but to deal with it adequately would require much more space than is available here. Moreover, it does not require extensive treatment here, for Roosevelt, Stimson, and Hull did not need any encouragement and support from the Communists in their determination to pressure Japan into war with the United States.

Most basic, perhaps, was the fact that Litvinov sold his doctrine of “collective security” to the Popular Front politicians in Europe, and this was adopted by the American Liberals as the dominant consideration in their pro-war propaganda in the United States. This matter has been treated in detail by Professor James J. Martin in his American Liberalism and World Politics, 1931-1941. The liberal propaganda was most potent in supporting American intervention in the European War until Hitler failed to provide the expected provocation to war on the Atlantic.

In Asia, the predominant motive of the Communists in supporting war against Japan was provided by the fact that Japan was the main bulwark against Communism in the Far East. But Russia left this propagandist operation chiefly in the hands of the Communists of Asia, mainly those in China, since Russia had to move cautiously to avert vigorous Japanese defensive movements against Siberia. The Chinese Communists pressured Chiang kai-Shek to act aggressively against Japan, and they were encouraged by the pro-communist figures in Roosevelt’s entourage in Washington. After England became involved in war in Europe, and especially after Hitler attacked Russia, the latter stepped up its pressure on the Chinese Communists to involve the United States in war with Japan.

But it was not until the Russian spy in Tokyo, Richard Sorge, informed Stalin in mid-October 1941 that Japan would move southward and not molest Siberia, that Russia began in earnest to influence American action against Japan. Prior to Hitler’s attack on Russia on June 22, 1941, the most publicized Soviet attitude in the United States had been anti-interventionist. American Communists sought to line up with the America First organization until they became embarrassing to the latter and its leaders repudiated any communist support, which evaporated after Hitler’s attack. But Russia had never abandoned its previous cautious support of pressure against Japan in the Far East.

The Lauchlin Currie-Owen Lattimore episode was only a dramatic item in this broader campaign of the Communists against Japan in the Far East. Lauchlin Currie, an assistant-President in the White House circle, was a strong pro-communist sympathizer, perhaps a member of the party. Owen Lattimore, who was similarly pro-Communist, but not personally a Communist, occupied the somewhat curious position of American adviser to Chiang kai-Shek in China. When Roosevelt, Hull, and even Stimson, at the insistence of Marshall and Stark, were considering a modus vivendi with Japan to gain time in order better to prepare for a Pacific war, Lattimore sent a strongly worded cablegram to Currie protesting against any such temporary truce with Japan. The cablegram was vigorously supported by Currie and it has been regarded by many historians as constituting the final item which induced Hull to kick over the modus vivendi and send his ultimatum to Japan.

There were other far more basic, communist influences on items with regard to Hull’s ultimatum to Japan which have been overlooked even by many revisionist historians. The most interesting of these is the extent to which the terms of Hull’s ultimatum reflected the views of Harry Dexter White, the pro-communist brains of the Treasury Department, Felix Frankfurter having once observed that secretary Morgenthau did “not have a brain in his head.”

On November 18, 1941, Morgenthau sent to Hull a memorandum drafted by White setting forth proposed terms that should by presented to Japan by Hull. They were so drastic that it was obvious that Japan would never accept them. Nevertheless, Maxwell Hamilton, the chief of the Far Eastern division of the State Department, read the Morgenthau-White memorandum and said that he found it the “most constructive one which I have yet seen.” He revised it slightly and filed it with Hull, who had this Hamilton revision before him when he drafted his ultimatum of November 26th to Japan. Actually, no less than eight of the ten points in Hull’s ultimatum to Japan embodied the drastic proposals of the Morgenthau-White memorandum.

Despite all this volume of evidence of communist pressure in the Far East for war between the United States and Japan, I remain unconvinced that it exerted any decisive influence upon Roosevelt, who, after all, determined American policy toward Japan. Roosevelt had made up his mind with regard to war with Japan on the basis of his own attitudes and wishes, aided and abetted by Stimson, and he did not need any persuasion or support from Communists, however much he may have welcomed their aggressive propaganda. If he had desired to preserve the modus vivendi he would have had no hesitation in repudiating Hull’s action. Hence, it remains my conviction that the contention that Soviet Russia exerted any preponderant influence in pushing the United States into war with Japan must be discarded. This also applies to the belief that Churchill, who was then working hand-in-glove with the Russians, exerted decisive influence on Roosevelt in his pressuring the Japanese into war. Roosevelt was in no way dependent on Churchill’s support; the reverse was the case. The responsibility for the final action in pressing Japan into war was that of Roosevelt, and this must be judged solely on the basis of its wisdom with respect to the national interest of the United States at this time. The apologists for Roosevelt, from Thomas A. Bailey to T. R. Fehrenbach, have contended that our national interest required our entry into the war and justified Roosevelt’s “lying” the country into the conflict to promote our public welfare.

For at least fifteen years after the attack on Pearl Harbor, most revisionist historians still believed that by December 4th or 5th, at the latest, virtually all the top officials in Washington, civilian and military, were convinced that, in the event of war, the Japanese would first attack Pearl Harbor. They based this conclusion chiefly on the whole broad historical background and the traditional naval strategy in the Pacific: the assumption that Japan would never start a war without making her first move an attempt to destroy the American Pacific fleet, wherever it was stationed. This was necessary to protect the Japanese flank before they could safely move into the southwest Pacific and the East Indies or go north to attack Siberia, unless they could be assured of American neutrality, and nothing in Roosevelt’s foreign policy gave the Japanese any reason to expect American neutrality. By mid-summer of 1941 it seemed evident that Roosevelt and Stimson were determined to wreck Japan by either economic pressure, military operations, or both.

These revisionist historians were also familiar with the series of Bomb Plot messages which clearly pinpointed Pearl Harbor as the target of any Japanese surprise attack on the United States. They were also well acquainted with the fact that our Navy had been holding maneuvers for years off Hawaii, long before the Pacific fleet was retained there in the spring of 1940, to discover the nature and prospects of a surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Unfortunately, the prospect of success for Japan seemed very good indeed, and hence it was taken for granted for years that any evidence of imminent hostilities between the United States and Japan would bring with it prompt action on the part of Washington to keep Pearl Harbor on the alert for a prospective Japanese attack, and ready to anticipate and repel one when it came. When this Japanese action did not take place before December, 1941, it was logically assumed that the top officials in Washington, acquainted with all the evidence that war was at hand, must have been personally prevented from warning Short and Kimmel, and only one man could give such an order and have it obeyed. That person was Franklin D. Roosevelt. Hence, he must have ordered all these top officials not to warn Short and Kimmel until it was too late for them to detect and repel the attack.

We now know that this interpretation needs some qualification, even though, as presented by Admiral Robert A. Theobald and other informed experts, it seemed to be soundly based upon both the factual historical background and sound logical inference. In the first place, any such general order by Roosevelt might have been very difficult to sustain. There were just too many important officials to be restrained by such an order without a considerable possibility that there would be a leak or disobedience somewhere. This is one point on which the views of Admiral Samuel E. Morison, in his article in the Saturday Evening Post, of October 28, 1961, are in my opinion worthy of consideration, although the reasons he gives for it are in part erroneous. It would obviously have been rather risky for Roosevelt. Some of these numerous officials who had to be warned to keep silent might reveal Roosevelt’s order to black out Pearl Harbor, and this would have been disastrous to both Roosevelt’s political career and military plans.

It is only fair, however, to present Commander Hiles’ defense of Admiral Theobald’s contention that Roosevelt could have ordered that Short, Bloch and Kimmel were not to be warned of the threat to Pearl Harbor without any great personal risk of exposure. The so-called chain-of-command procedure would have made this possible without too much risk. Roosevelt did not have to reach all of his important subordinates personally. The Joint Board of Command was the highest military authority in the land, except for the President. It was made up exclusively of the armed forces, with Marshall and Stark at its head. Even the Secretaries of War and the Navy were not members and had no voice in the deliberations of the Joint Board, although as a matter of routine its reports to the President were submitted through the Secretaries and the latter could add such comments as they wished to make for what value they might have from the military point of view. No person except Roosevelt had any jurisdiction over the Joint Board. Consequently, it is not at all difficult to discern how Roosevelt could control the situation with no great difficulty or risk; from the Joint Board on down it was solely a matter of the chain-of-command. Certainly, there might be some minor leaks and some disobedience, as in the “contact Rochefort” message in connection with Winds Execute, the “October (1941) revolution” in the Office of Naval Intelligence, and in the Sadtler-Akin “pipeline” arrangement, not to mention the efforts of Sadtler, Bratton and McCollum to get past the Marshall barrier. Roosevelt was well covered up because he would almost never place any orders in writing—they were nearly invariably verbal.

At any rate, Roosevelt appears to have kept Hawaii in the dark about the threat to Pearl Harbor without any blackout orders of which we have any definite evidence save those to Marshall, Arnold and Stark, and then not until December 4th.

Finally, and most important, it appears that Roosevelt may not have needed to order many of his leading subordinates against warning Short and Kimmel. These top officials seem to have become unduly absorbed by the fact that all the known Japanese military movements, and these were on a grand scale and rather conspicuously displayed, indicated that Japanese task forces were moving down into the southwest Pacific and the East Indies, and there were no known Japanese fleet movements that appeared to threaten Pearl Harbor. Some writers believe that this virtual parading of Japanese power moving southward was in part deliberately designed to distract attention from Pearl Harbor. This is doubtful. The extensive movement southward was a basic part of the campaign connected with the attack on Pearl Harbor, and had to be timed accordingly.

To this, and a very important consideration, was added the concentration of the top brass naval authorities on the strategic implications of the ABCD agreement and the Pacific War Plans, Rainbow 5 (WPL 46), drawn up in April, 1941, and approved verbally by Roosevelt in May and June, which envisaged the launching of the first Japanese attacks in the Far East. The extensive Japanese task force movements southward in November, 1941 appeared to confirm this assumption. The top naval officers, Stark and Turner, had warned that the economic strangulation of Japan in late July would certainly mean that Japan would have to move southward to get, by force if necessary, the indispensable vital supplies that were denied to her by the July embargo imposed by the United States, Britain and Holland. Both the navy and the army leaders were fully aware that Rainbow 5 (WPL 46) provided that the United States would make war on Japan if the latter went too far in this quest, even if there was no Japanese attack on American forces or territory.

Very significant evidence of this concentration on the Far East, especially by the Navy, on the eve of Pearl Harbor is provided by Admiral Beatty, the aide of Secretary Knox in 1941. He recalls that, at the last meeting of the top officers of the Navy with Knox on the afternoon of December 6th, Knox inquired as to whether the Japanese were about to attack the United States. Turner, who, as usual, spoke for Stark, answered rather dogmatically in the negative, and went on to say that he believed Japan would first strike the British in the Far East. Beatty asserts that there was no dissenting voice from any of the navy officers present, from Stark down. Perhaps more conclusive as evidence of the shift of interest and concern from Pearl Harbor to the Far East is provided by the agenda and discussions of Roosevelt’s “War Cabinet,” made up of Roosevelt, Stimson, Knox, Marshall and Stark, on November 28th, and of the final conference of Stimson, Knox and Hull on the forenoon of December 7th. In both cases the main subject and problems discussed were the movements of Japanese forces to the southwest Pacific, the obligations of the United States under ABCD and Rainbow 5 to check these by war, if necessary, and the question as to whether the country would unite to support a war which had not been started by an attack on American territory or forces.

It is desirable to point out, however, that the newer Revisionism on Pearl Harbor, which is based on the assumption that most of the top civilian and military authorities in Washington expected that the Japanese would almost surely begin their aggressive action in the Far East, also needs qualification, just as does the older view that Roosevelt specifically ordered them all not to send any warnings to Pearl Harbor.

This newer interpretation, stressing the Far Eastern fixation of most top Washington officials from early November to the Pearl Harbor attack, does not account for the failure to supply Short, Bloch, and Kimmel with the planes and other equipment which they had requested early in 1941 to enable them to carry out the necessary reconnaissance to detect and repel any Japanese attack; the failure in the summer of 1941 to provide Pearl Harbor with a Purple machine or even to assign Commander Rochefort and his large and capable cryptanalytical group the task of intercepting, decoding, and reading the other Japanese diplomatic messages in J-19 and PA-K2; the blacking out of Short after the economic strangulation of Japan in July and of Kimmel after Argentia with respect to the nature of American negotiations with Japan; or the reasons why Stark and Turner, as well as the responsible army officials, refused to permit the Bomb Plot messages to be sent to Pearl Harbor in October 1941, and later on.

Their concentration on the Far East may account for the attitude and operations of the top echelons in the Army and Navy after the extensive ship movements of the Japanese into this area in November, 1941, but it fails to provide an adequate explanation of the obvious efforts to keep Short and Kimmel from getting the essential information available in Washington long before that time or of sending them bogus “warnings” on November 27th.

Pending a better explanation, which has never been provided by Roosevelt’s defenders, it must be assumed that this long continued and unbroken effort to keep Short and Kimmel in the dark as to the tense diplomatic situation between the United States and Japan was keyed to Roosevelt’s persistent recognition that he must have an attack by Japan, once it became rather clear that Hitler would not rise to the provocative bait provided by American convoying on the Atlantic. The situation surely calls for something more fundamental than the trivial and impersonal “noise,” which is offered by Roberta Wohlstetter in her defense of Roosevelt and his bellicose collaborators in Washington.

As late as December 1st, it is very possible that Roosevelt himself feared lest Japanese aggressive action might start in the southwest Pacific and the East Indies and not provide any prior and direct attack on the United States. On that date, he sent a note to Admiral Hart at Manila ordering three “small vessels” to be fitted out at Manila, each manned by Filipino sailors, commanded by an American naval officer, flying the American flag, and carrying a machine gun and a visible cannon. They were to be sent out to specified positions where they could be fired upon by the Japanese task forces that were moving southward. This would give him the attack on American ships that he vitally needed to get the United States into the war by the back door of Japan, unite the country behind him, and also save the Pearl Harbor fleet if the Japanese attacked this bait in the Far East before Nagumo reached Pearl Harbor.

The Democratic platform of 1940 had declared that the United States would not enter the war unless attacked. The anti-interventionist sentiment in the United States was so overwhelming in 1940 that, during the campaign of that year, Roosevelt thought it necessary repeatedly and vigorously to assure the American public that he would avoid war, culminating in his famous speech in Boston on October 30, 1940, in which he told American mothers and fathers, “again and again and again” that their sons would not be sent into any foreign war.

But on the heels of his victory in the election of 1940, Roosevelt, as noted earlier, started military conferences with the British which, in April 1941, ended at Singapore with the ADB agreement, to include the Dutch. It was all implemented by ABCD and Rainbow 5, which specified that if the Japanese went beyond a certain arbitrary line in the Southwest Pacific-100˚E and 10˚N—and even threatened the British and Dutch possessions there, the United States would enter the war against Japan even if American territory, forces and flag were not attacked by the Japanese. Roosevelt actually desired, above all, to avoid having to enter the war in this manner. If this happened, he would have to reveal that he had deceived the American public in his campaign promises and would not have anything like a united country behind him.

This was obviously what induced Roosevelt to order the three “small vessels” to move out from Manila into the path of the Japanese task forces as they sailed southward. Aside from a futile trip by the dispatch ship, Isabel, which was not even repainted, only one of the small vessels” had left Manila harbor before the Japanese struck at Pearl Harbor, and this ship, the little schooner Lanikai, was not able to proceed beyond Manila harbor into the path of the Japanese task forces before the attack on Pearl Harbor. This so-called Cockleshell ship stratagem of the three “small vessels,” first noted among revisionist writers by Dr. Frederic R. Sanborn in his Design for War (1951) has been vividly described by Admiral Kemp Tolley, commander of the Lanikai, the second ship that was ready to leave as “bait” for the Japanese, in the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings of September, 1962, and October 1963.

Commander Hiles, a close and well-informed student of the Pearl Harbor episode, believes that, although Roosevelt was in all probability convinced before December 1st that the Japanese planned to attack Pearl Harbor, he devised the three “small vessels” scheme to get a prior attack which would start the war in a politically satisfactory manner without sacrificing the Pearl Harbor fleet. This is undoubtedly true, but if this was his motive Roosevelt thought up the plan some days too late. The Japanese hit Pearl Harbor before even one of the three “small vessels” could get fired on. The order to equip and dispatch them should at the latest have been sent coincidental with Hull’s ultimatum on November 26th. Indeed, it should have been sent by November 5th, when it was evident that the Japanese proposals for settling American-Japanese relations peacefully which were to be offered in November were the final Japanese gesture that could preserve peace, and Roosevelt knew that the situation built up by Stimson, Hull and himself precluded the possibility of accepting any Japanese proposals short of a virtual surrender. The memory of the sinking of the Panay on December 12, 1937, and the bellicose excitement caused by the accidental attack on one small American vessel should have inspired an order identical with that he sent to Admiral Hart on December 1, 1941. Roosevelt should not have needed the report on the Japanese hostility to the gunboats passing Formosa on November 29th and 30th to inspire the note to Hart.

Secretary Henry Morgenthau tells of a conversation with Roosevelt as late as the morning of December 3rd in which the latter seemed frustrated, despairing of any Japanese attack, and feared that he and Churchill might have to plan and strike the first blow, an emergency which Roosevelt desperately wished to avoid for political reasons, as Stimson has revealed in his Diary and was stipulated in the messages to Short on November 27th and to Kimmel on November 29th.

On December 4th, everything seemed changed. Roosevelt appeared assured that the Japanese had decided to attack Pearl Harbor as their first stroke, and he now seemed convinced that all possible emphasis and effort in Washington must be placed on keeping Short and Kimmel from being warned of an impending attack, although he was still hoping for an attack on one of the three “small vessels” before the Japanese could reach Pearl Harbor.

There is no definitive documentary evidence which has thus far been revealed and fully proves that Roosevelt had been explicitly informed by Decemer 4th that Japan would attack Pearl Harbor as the first act of war. There may be none until the voluminous secret correspondence between Roosevelt and Churchill, which began in September, 1939, is opened to reputable investigators. Even in this event, it is likely that so incriminating a document will have been removed from any American copy of the files, following the pattern of the removal of so much incriminating material from the American Army and Navy files dealing with Pearl Harbor.

There are three reputable reports from British intelligence in the Far East that, between November 30th and December 7th, London was informed that the Japanese would attack Pearl Harbor on December 7th. If these reports, or any one of them, are accurate, then there is little doubt that Churchill would have passed the information on to Roosevelt. General Bonner Fellers, who was in Army Intelligence in the Near East and located at Cairo, has given me personally and by letter the following relevant information. Here, quoting from his letter of March 6th, 1967:

About 10:00 A.M., Saturday, December 6, 1941, I walked into the Royal Air Force Headquarters in Cairo. The Air Marshal who was then in command of the RAF Middle East sat at his desk. Immediately, he opened with: “Bonner, you will be at war within 24 hours.” He continued: “We . . . have a secret signal Japan will strike the U. S. in 24 hours.” . . . I had been in Egypt for about fifteen months. During that time no word whatsoever had been sent to me from G-2 in Washington that Japanese-American relations were strained.

In the confession of the Russian spy in Tokyo, Richard Sorge, he stated that in October, 1941, he had informed Stalin that the Japanese intended to attack Pearl Harbor within sixty days. Stalin may well have passed this on to Roosevelt in return for Sumner Welles’ helpful gesture in informing him of Hitler’s plan to attack Russia. One of the last things that Stalin would have wished to have happen at this time in the Far East was the destruction of the American Pacific fleet. Most important of all is the fact that a very prominent American Army Intelligence officer in service in the Far East during 1941, whose name I am not yet free to mention, had gained knowledge of the Yamamoto plan to send a task force to attack Pearl Harbor and sent three separate messages to Washington revealing this information, and at least two of these reached the Army files well before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Moreover, as will be clear later on when we deal with the Merle-Smith message, it is entirely possible that Roosevelt could have read this on the evening of December 4th, Washington time, and known that the United States was already involved in war because the Dutch had implemented ABCD and Rainbow 5 (A-2) on December 3rd, Washington time. The message must have been available in Washington by the 5th. Perhaps even more instructive and revealing is the fact that some time before 5:30 P.M. on December 4th, Roosevelt had discussed the Far Eastern situation with Stark and had approved Stark’s informing London and the Dutch that Roosevelt was in favor of warning Japan that if its forces crossed the magic line in the southwest Pacific this would be regarded as a hostile act and Japan would be attacked by the ABCD powers. Roosevelt was thus approving the ABCD (ABD) agreement more than 24 hours before Halifax approached Hull, and he should have been well prepared for the contents of the Merle-Smith message.

Another unimpeachable item of information which indicates that Roosevelt was in all probability informed by December 4th that the Japanese were planning to attack Pearl Harbor on December 7th has not previously been presented, but, fortunately, it has neither been destroyed nor suppressed. This is an entry in the History of the Sacramento Air Service Command for December 6, 1941. This History, declassified in 1948, had been casually lying around for some time but had not been carefully examined even by revisionist historians. A copy was noticed by a revisionist student who was working for his master’s degree at Indiana University on the subject of logistic failures at Pearl Harbor. Having plenty of money, he had travelled about looking for sources. When visiting the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base at Dayton, Ohio, he found the History of the Sacramento Air Service Command available for inspection by interested parties admitted to the Base. Reading the entry for December 6, 1941, he was immediately impressed with its significance and sent it to Commander Hiles, who was assisting him in locating source-material for his study. Hiles has been the first revisionist expert to develop the full significance of this material.

General Henry H. Arnold was the chief of the Army Air Corps and one of Marshall’s deputy chiefs-of-staff. Few men could have been more vitally needed at this critical time in Washington, the center of activities in getting ready for the war with Japan which had been regarded as imminent ever since Hull sent his ultimatum on November 26th. Its approach was amplified and confirmed by the codes destruction intercepts of December 1st and 2nd and by the Winds Execute intercept of December 4th, the latter revealing that when war came Japan would attack the United States and Britain, and not Russia. Against this background, it is obvious that Arnold could have been spared from Washington only if he were to carry out an assignment of the utmost confidential and strategic significance in the face of a Japanese attack at any moment. On December 5th, Marshall ordered Arnold to make a transcontinental trip to Hamilton Airfield in California.

Arnold’s mission was ostensibly to expedite the departure of a small squadron of some twelve B-17 bombers from Hamilton Airfield to the Philippines via Hawaii, and to repeat orders concerning the continuation of reconnaissance while en route over Japanese mandated islands in the mid-Pacific. This assignment surely did not justify a long trip by an officer of Arnold’s rank, experience and ability, even if there had been no crisis in Japanese-American relations and he had all the time in the world. It was something that could have been executed by any experienced captain, major or colonel in the Air Force at Washington. There was nothing complicated or unusual about it, since this was by no means the first time that a squadron of B-17 bombers had been sent to the Philippines via Hawaii and had photographed the Japanese islands. It does not seem reasonable, or even credible, that such a lofty and capable military figure as General Arnold would have been sent from Washington to carry out so relatively trifling a mission as Watching a few bombing planes depart from the Pacific Coast, especially when it was assumed that the first Japanese moves in the approaching hostilities would be made in the air and require Arnold’s full attention at Washington Hence, we are compelled to look for the actual reason behind the Arnold mission.

It so happened that December 4th was the day on which the Chicago Tribune published the implications of Rainbow 5, which fully proved that Roosevelt had been planning war over many months, if necessary without any attack on American forces, while at the same time he was assuring the American people that all his actions were designed to keep the United States out of war. Naturally, this sensational exposure created great excitement in Washington, and Roosevelt ordered Marshall to try to locate the source of this embarrassing leak.

After the war, it was revealed that it was an emissary from General Arnold’s office who facilitated the leak of Rainbow 5 to Senator Burton K. Wheeler, who, in turn, showed it to the Washington representative of the Tribune, all three of them patriotically motivated by the hope of forcing more adequate attention to the needs of the Army Air Corps if the United States was to become engaged in a farflung Pacific war. Some writers, working mainly on hindsight, have alleged that Marshall wished to get Arnold out of Washington for the moment as soon as possible, lest his relation to the “leak” be discovered. I personally doubt this explanation, although Marshall was feverishly active in searching for the sources of the leak, and Colonel Deane was working for him on this subject when he saw Marshall at his office in the Old Munitions Building about 10:00 on the morning of December 7th.

Whatever the basis of Arnold’s mission, it had to be one of a secret, serious and responsible nature, commensurate with Arnold’s rank, distinction and ability. The account of what Arnold actually did when he was on the coast provides the soundest explanation of his mission and it rests on facts that cannot be refuted. They are the following:

The same message that had been sent to General Short on November 27th, ordering action at Hawaii to prevent local sabotage had also been sent to the Army headquarters on the Pacific Coast at the Presidio in San Francisco. Accordingly, appropriate steps had been taken at the McClellan airfield and the planes had been bunched there to safeguard them against local sabotage. Presumably, they were also bunched at the Hamilton airfield, but neither Arnold nor the Sacramento History mentions this matter. As the entry in the History of the Sacramento Air Service Command for December 6th puts it: “It looked like all the planes on the Pacific coast were at McClellan field.” General Arnold “brought word of the imminence of war, expressed stern disapproval of the planes being huddled together and ordered them dispersed.” This was done at once and as rapidly as possible, despite heavy rain and special local difficulties at the moment. There were no revetments, so the planes had to be flown to other airfields.

This dispersal of the planes was an order that would not have been accepted or obeyed if given by a junior officer however capable and well informed. It superseded the Washington order of November 27th to the Hawaii air command in which Arnold had participated and had supplemented by later directions on how to assure full protection against local sabotage.

The action taken by Arnold can only be explained on the ground that Marshall and Arnold had learned through December 4th that the Japanese were planning to attack Pearl Harbor on December 7th. Fearing an attack on the Pacific coast, as well, they decided to order the dispersal of the planes that had been bunched there in accordance with the orders of November 27th and 28th. Marshall and Arnold did not dare to order the dispersal of Short’s planes at Hawaii, although Hawaii is 2500 miles closer to Japan than California, and hence far more vulnerable to a Japanese air attack, but they decided to take a chance on alerting the Air Force on the Pacific coast. Both Marshall and Arnold were well known for their fear of an attack there.

In other words, Marshall and Arnold were greatly alarmed over the information that the Japanese would attack at Pearl Harbor on the 7th. While their hands were tied with respect to alerting Short and Martin at Hawaii, they did have momentary freedom of action on the Pacific coast and could surreptitiously alert McClellan airfield without creating any great excitement or publicity. In any event, by the next morning any possible adverse reaction to alerting the Air Command in California would be rendered redundant by the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor. It is instructive to note that nowhere in his testimony about his trip to California did Arnold mention actually visiting McClellan airfield, which indicates that he wished to leave this visit in obscurity for obvious reasons. Moreover, he made it a surprise visit, thus avoiding the normal honors and publicity attending a visit by the head of the Air Corps in Washington.

This would seem to be the only rational and valid explanation of Arnold’s mission to California on the eve of Pearl Harbor; the expediting of planes to Hawaii and the Far East was only the excuse or coverup. Otherwise, we face the double paradox of the century for Roosevelt’s defenders to explain: (1) pulling Arnold out of Washington during the two most critical days of the whole crisis for a perfunctory and routine operation, and (2) keeping Short’s planes bunched in Hawaii, while dispersing the planes in California. The Arnold mission and action is surely one of the best proofs which we shall have that Roosevelt had advance knowledge that the Japanese planned to attack Pearl Harbor on December 7th until the time comes when we can produce absolute documentation of this fact.

One can well imagine Arnold’s feelings as he sent off the B-17’s to Hawaii, unwarned that they might in all probability be heading for destruction the next morning. Their guns were unfit for use and there was no ammunition for them, the latter having been dispensed with to provide more room for fuel. Having been sent to California ostensibly to dispatch these planes, not even Arnold dared to restrain them and cancel their flight. His emotions must have been even deeper when he thought of Short’s huddled planes, which would also be destroyed on the ground by Japanese bombers the next morning, and of Kimmel’s battleships that would actually provide sitting-ducks for the Japanese bombing and torpedo planes, but he did not dare to alert Short, Martin, Bloch and Kimmel as to their impending fate.

That Arnold gave the officers at the Sacramento Air Service Command the definite impression that war was right at hand is evident from the statement in the History that: “When word came on December 7th, 1941, that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor it did not cause any surprise!”

I shall only mention in passing a possibly significant slip of the tongue on the part of Roosevelt at an important meeting of Roosevelt, Hull, Stimson, Knox, Marshall and Stark at noon on November 25th, which has attracted the interest of some revisionist scholars. Roosevelt observed that the United States might be attacked “perhaps next Monday for the Japanese are notorious for making an attack without warning.” One revisionist critic has queried: “Why did he say ‘Monday’, which is Sunday in the United states? A dispatch from the Orient from anyone except our military or diplomatic services normally used the Far East date rather than ours. Somehow, I just cannot believe that Roosevelt would even have said Monday unless it slipped out inadvertently as a result of his having read some warning message from the Far East.” I am not inclined to overplay this item, and will leave it merely with the suggestion that Roosevelt’s defenders give a better explanation for his mentioning “Monday” rather than “Sunday.” This is something that had long aroused my curiosity.

Many revisionist historians now regard the above material as adequate to demonstrate that Roosevelt must have received impressive and precise information by December 4th that Japan was planning to attack Pearl Harbor as the first act of war. Nevertheless, it is probably best to recognize the plausibility and relevance of this assumption but to depend more upon circumstantial evidence, based chiefly on the trend of events from the 4th to the 7th which has now been presented in detail. This is actually overwhelming, while the circumstantial evidence—and there is no other evidence—supporting the contention that even after December 4th Roosevelt still did not expect an attack on Pearl Harbor is extremely fragile and unconvincing, as we shall now indicate.

One argument for Roosevelt’s ignorance of an impending attack is that, as a lover of ships and especially our naval ships, he would never have sacrificed our Pacific fleet to insure his needed attack. But he could have known or seen to it by December 5th that the carriers, the heavy cruisers, and most of the destroyers and pursuit planes had been sent out of Pearl Harbor, leaving mainly the battleships, which were chiefly of sentimental concern in the light of contemporary methods of naval warfare. This had been done as a result of Stark’s order to Kimmel on November 27th. When Roosevelt was trying to “sell” his idea of a long patrol line, rather than a double line, to the Orient, he did not seem disturbed about the prospect of losing even a few cruisers. He wanted to see them “popping up here and there” to fool the Japanese. He may have loved ships but he loved politics and his own political ambitions far more.

Even less plausible is the contention that Roosevelt would not have sacrificed the lives of thousands of American sailors, soldiers and marines to obtain the attack. He was then playing for high and crucial political stakes in which a few dreadnaughts or a few thousand human lives were hardly a consideration to override policy, however regrettable their loss. Roosevelt’s program was primarily political rather than military or humanitarian. He surely knew that the war into which he was seeking to put the United States would cost millions of lives. Moreover, it is well established that Roosevelt did not anticipate as great destruction of ships and life as the Japanese bombers actually wrought. As Secretary Knox observed after he visited Roosevelt in the White House immediately following the news of the attack: “He expected to get hit but did not expect to get hurt.” There can be little doubt that the Cockleship plan of December 1st was designed to get the indispensable attack by a method which would precede the Pearl Harbor attack, avert the latter, and save the Pacific fleet and American lives.

It is maintained that Roosevelt could have had his Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor without its being a surprise and the forces of Short and Kimmel could have been alerted as to the prospective attack and repelled it with no serious losses. This fantastic suggestion runs counter to all the well-known facts. Walter Lord and Gordon W. Prange, the main writers on this subject, have shown with impressive evidence that Admiral Nagumo would have been ordered to turn back if there was any impressive evidence that Pearl Harbor had been fully alerted to the prospect of an attack, even after the order of December 5th to “climb Mount Niitaka.” Of course, we do not need the testimony of Lord and Prange for these facts are fully supported by the available official documents. There could not have been any Japanese task-force attack on Pearl Harbor unless it was a surprise attack.

Finally, there is the fact that Roosevelt sent a message to the Japanese Emperor on the night of December 6th, after he knew that the negative reply to Hull was coming in, suggesting a peaceful settlement, but even Hull has admitted that this was only sent “for the record” after it was too late. Roosevelt had stressed this point of having a good formal record to Harry Hopkins when Lieutenant Schulz brought to him, on the evening of December 6th about 9:30, the detailed Japanese reply to Hull, which everybody in top Washington circles had assumed would be the moment when Japan would attack this country. Moreover, as will be indicated later, on the afternoon of the 6th Roosevelt had approved the implementation of Rainbow 5 by the Dutch and British, which meant that we were already at war with Japan, actually had been since December 3rd, Washington time when the Dutch invoked Rainbow 5 (A-2).

There is an alternative cogent, logical and completely factual explanation of Roosevelt’s decision on December 4th to concentrate on preventing any warnings from being sent to Short and Kimmel. This does not rest upon circumstantial evidence or any assumption that Roosevelt must have received precise information by that time that Japan was about to attack Pearl Harbor.

Through the “three small vessels” stratagem he had done all that he could to secure his indispensable attack in the Far East. There was nothing left here except to wait and hope that one of the “small vessels” would be fired on. This left Pearl Harbor as the only other remotely probable place that would invite and be vulnerable to a surprise Japanese attack. Hence, nothing should be allowed to obstruct or divert this final crucial necessity. There is no doubt that he would have preferred a prior attack on one of the three small vessels” and thus save the Pearl Harbor battleships. He hoped for this until the morning of December 7th.

It is my firm personal opinion that this is the one unassailable and impregnable explanation of Roosevelt’s action on December 4th for revisionist historians to accept prior to published documentary evidence that Roosevelt had been definitely and personally informed of an imminent Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. This is sound and true, even though the circumstantial evidence of his having received such information is overwhelmingly more convincing than the Blackout and Blurout contention that he was surprised and shocked by the attack at Pearl Harbor, at least beyond the shock over the actual extent of the devastation produced by the attack. By December 4th he had brought the country to the brink of war. Its outbreak had to come through an attack on American forces if he was to have a united country behind the war effort. The Far East, via the three “small vessels,” and Pearl Harbor were the only places that remained at which he could reasonably expect a surprise attack. The Philippines, as has been indicated, had been so well informed of Japanese intentions and operations through the Sadtler-Akin pipeline and their own intercepts that MacArthur could hardly have been surprised by hearing of immediate Japanese aggression. Moreover, Admiral Hart’s Asiatic Fleet was so small that to destroy it would not have furnished much protection for the extensive movements that the Japanese had planned in the Pacific, once the war had started. Kimmel’s powerful Pacific fleet would have remained intact.

Now that it has been shown that apparently few top officials in Washington except Roosevelt, Marshall and Arnold—and possibly Stark after the 4th—expected that the Japanese would first attack at Pearl Harbor, and that Roosevelt may not have ordered all the top brass to refrain from warning Short and Kimmel, we may indicate how he did prevent any warning from being sent to Short and Kimmel between December 4th and 7th.

Roosevelt first passed on his logical conclusions or specific information relative to the impending attack on Pearl Harbor to Generals Marshall and Arnold on the 4th of December. Marshall had very special reasons for being subservient and trustworthy to Roosevelt. The latter, influenced by Mrs. Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins, had rescued Marshall from obscurity after his conspicuous failure in the armed command of the famous Eighth Regiment, and MacArthur had relegated him to the post of an instructor of the National Guard in Illinois. Roosevelt promoted Marshall to be full general over some thirty-four superior officers, and even made him Chief-of-Staff of the Army. There is no doubt that Marshall also greatly admired Roosevelt personally and, as the events of December 4-7 demonstrated, put his loyalty to the President above his loyalty to the military services and his country.

Nothing else could account for Marshall’s strange behavior from December 4th to 7th, right down to his delayed sending of the “too-little-and-too-late” message to Short at 11:50 A.M. on the 7th, which we have already described. Neither Marshall nor Stark personally wished the United States to go to war with Japan in 1941 because they did not feel we were prepared to wage a large-scale Pacific war, to say nothing of a two-front war in Europe and the Pacific. They so reported on November 5th. They favored the modus vivendi of late November which Roosevelt and Hull kicked over, followed by Hull’s sending an ultimatum to Japan on the 26th. There is no reasonable doubt that if Marshall had been left to his own convictions and impulses he would have sent Short a real warning at least as early as November 27th, elaborated it repeatedly, and been in his office on the afternoon and night of the 6th of December conferring with Short, if this had been needed. Obviously it would not have been needed to deal with any immediate attack on Pearl Harbor if Short had actually been warned on the 27th. Even the Army Pearl Harbor Board stated that a clear and definite warning to Short on November 27th, indicating the threat of an immediate Japanese movement against Pearl Harbor, would have led to action by Short which would have averted the attack.

As Admiral McCollum and others have revealed, Roosevelt quietly directed on December 4th that no warning communications could be sent to Pearl Harbor unless cleared by Marshall, which bottled up Army Intelligence and the Signal Corps. Marshall immediately informed Stark of this directive, thus preventing any leak to Pearl Harbor through the Navy. This precluded sending Short or Kimmel the Winds Execute message which was received on the 4th and was the most important and decisive intercept that had been received indicating immediate war with Japan, as well as all later evidence of an attack on Pearl Harbor.

Whether Roosevelt personally emphasized to Stark this arrangement to black out Pearl Harbor before the night of the 6th is uncertain. When the news of the arrival of the Japanese reply to Hull was brought to him about 9:30 on the evening of the 6th, Roosevelt called Stark on the telephone, found that he was out for the evening at the theater, and left word that Stark was to call him on his return, which Stark did.

The next morning, when Noyes, McCollum and Wilkinson showed Stark the “Time of Delivery” message, and indicated to him that this probably meant a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor about 7:30 A.M. Pearl Harbor time. Stark called Roosevelt, rather than Kimmel, and thereafter showed no interest in contacting Kimmel, even ignoring the pleas of Noyes, McCollum and Wilkinson for a separate warning message to Kimmel. After discussing with Marshall the desirable content of the message to be sent to Short—the “too-little-too-late” farce—Stark only suggested, as a sort of afterthought, that this also be handed on to Kimmel by Short.

We have already dealt with Marshall’s strange behavior from December 4th to 7th and especially on the 6th and 7th. How much influence he had on the frustration and killing of McCollum’s clear message of precise warning to Kimmel on the 4th by Stark and Turner is not known. As reported in the officially accepted legend, on the afternoon of the 6th, as soon as he learned that the Japanese reply to Hull’s ultimatum would be coming in, which the Pilot Message clearly indicated meant immediate war, Marshall abruptly left his office and hid out somewhere, which he could not for a time remember but later on reported to be his official quarters. On the morning of December 7th, the Washington-Times-Herald published an item stating that Marshall attended a banquet of alumni of the Virginia Military Institute on the evening of the 6th, but this has never been confirmed or denied. Marshall did not appear again officially until Sunday morning, whether some time around 9:00 at Stark’s office, which seems most likely, or not until 11:25 at his own office. According to normal military procedure he should have been in his office all of Saturday afternoon and most of the night further informing Short and conferring about protecting Pearl Harbor.

If we accept the official legend of Marshall’s activities on December 6th and 7th, Japan might have attacked the Pearl Harbor fleet on the afternoon or night of the 6th and Marshall would have known nothing about it until he came out of hiding late the next morning. When he did, he only sent Short at 11:50 the brief, vague, ambiguous and equivocal “too-little-and-too-late” message, which was in no sense any warning that war was about to start and, least of all, that the Japanese would probably attack Pearl Harbor in about an hour. It gave Short little or no information that he did not already have, except for the Time of Delivery message, and Marshall deceived Short in withholding the significance he had attached to this when reading it in his office. Finally, he refused to use three rapid means that he had available to send his already “too-late” message to Short, but let it be sent by Western Union to San Francisco, and R. C. A. from San Francisco to Fort Shafter—not even marked urgent—with the result that it did not reach Short until the Japanese planes had returned to their carriers after the attack. The delay in sending the message and Marshall’s refusal to use a rapid method of transmitting it can only be explained as due to a desire to have it arrive too late for Short to take any action that might frighten off the Japanese attack. If we accept the more probable version, earlier described, that the message to be sent to Short had been agreed upon during Marshall’s conference in Stark’s office before 10:00 on the morning of the 7th, then the delay in sending it until 11:50 becomes all the more significant and unpardonable, to indulge in understatement.

Marshall saw to it that no warnings were sent to Pearl Harbor between the 4th and the 7th. The only alleged attempt to do so came on the night of the 6th, when Knox has asserted that he made a serious effort to send a clear and definite warning to Kimmel and to Admiral Hart, commander of the Asiatic fleet at Manila. This never arrived at Pearl Harbor or Manila and Knox could not find any record of what happened to it in Washington. Only Marshall had the authority to kill it if Knox actually ordered such a message to be sent of which there is some doubt.

As conduct on the part of a trained soldier, assumedly dominated by the ideals and professional stereotypes of those high in his profession, and having the supreme military responsibility for the protection of his country, it would seem both fair and reasonable to contend that Marshall’s conduct can be explained on only three grounds: mental defect, deliberately treasonable behavior, or carried out under orders from President Roosevelt. The last seems the only plausible and sensible interpretation. One thing is certain: however much Marshall was dominated and controlled by Roosevelt, his behavior during the brief period between December 4th and 7th perfectly performed the function of keeping Short and Kimmel in the dark about the danger of Japanese attack until the Japanese bombers appeared over the Pacific fleet. And this was all achieved with a minimum of risk and exertion on the part of Roosevelt. He only needed to give his blackout order directly to Marshall.

While we are on or near that subject, it is desirable to point out that altogether too much emphasis has been laid by both the defenders of Roosevelt and his “Day of Infamy” rhetoric and the revisionist critics on the alleged significance of possible “last minute” warnings late on the night of the 6th or the morning of the 7th, whether sent or unsent.

Unless the Japanese task force could have been frightened back more easily than is likely, even in the light of its jittery and timid commander, Admiral Nagumo, any warnings sent immediately after the first thirteen points of the Japanese reply to Hull’s ultimatum had been received, decoded and delivered before midnight of the 6th might not have made any great difference with respect to Nagumo’s carrying through the attack. The results could have been even more disastrous to the Pacific fleet than it turned out to be. As Admiral Nimitz and others have suggested, there might have been just time enough to get the ships out of port and on the ocean, in which case they might have been sunk in deep water and could not have been raised, salvaged and restored for action. There would have been plenty of Japanese planes available for a supplementary attack on the Army installations, machine shops, supplies and most important of all, the oil supplies, still above ground, which would have been far more of a disaster to the United States than the destruction of the battleship fleet.

There is little doubt that Short, Martin and Bellinger could have got many of their planes distributed, fueled and ready for battle and some in the air for reconnaissance, probably only to be shot down by the greatly superior air force on the six Japanese carriers. The unarmed B-17 bombers that came in on the morning of the 7th, some of them only to be immediately destroyed or damaged, might have been turned back. There is little doubt that greater damage could have been inflicted on the attacking Japanese bombers than took place in the actual attack, but it is doubtful if the devastation wrought by them would have been greatly lessened.

If a warning had been sent to Short and Kimmel when the Pilot Message had been decoded and read and the Kita message had been processed by mid-afternoon of the 6th, it might have been a quite different story. Defensive movements at Hawaii connected with an alert put in operation during the afternoon of the 6th might have caused the Japanese task force to abandon their bombing mission and turn back or to face an empty harbor. That would have made a great difference in the fate of the ships at Pearl Harbor. In this case, Kimmel could have put to sea with all his available ships, joined Halsey who was returning from Wake, linked up as soon as possible with Newton and Brown, and through a surprise attack perhaps have inflicted a serious surprise blow on at least a part of the returning Japanese task force whose location could have been rather precisely determined by Commander Rochefort at Pearl Harbor. Nagumo could have had no knowledge of the location of Kimmel’s reorganized fleet. In any event, Nagumo’s bombers would have found an empty harbor at Pearl Harbor and all of Kimmel’s warships out of sight beyond the horizon.

When it comes to later warnings that could have been given, but were not, such as Knox’s mysterious alleged message to Kimmel and Hart late on the night of the 6th, a warning to Kimmel by Stark shortly after 9:00 on the morning of the 7th, when Noyes, McCollum and Wilkinson explained to him the significance of the Time of Delivery message, and Marshall’s “too-little-and-too-late” message at 11:50, or even a clear and forthright one by Marshall at least two hours earlier, there is only a gambling chance that the disaster to the Pacific fleet would have been greatly lessened. As pointed out above it would have been worse had the ships been sunk in the deep Pacific beyond hope of salvage and repair. The failure to get off these last minute warnings promptly, or not at all, may have great significance for the historian and the moralist but they are far less important strategically.

It is only fair, however, to present here an informed critique by Commander Hiles of my opinions on the probable results of a warning if sent by Stark to Kimmel even as late as 9:30 A.M. on the morning of the 7th, when Stark was made to realize that the Time of Delivery message implied the probability of a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor at around 7:30 A.M. Pearl Harbor time. Actually, the bombers did not arrive until about 7:50. If, as McCollum maintains, Marshall was also in Stark’s office between 9:00 and 10:00 on the morning of the 7th and they had there decided to send a real warning to Short, this could have been sent by 10:00 A.M. instead of 11:50. Hiles admits that even a clear warning sent at 11:50 by the most rapid method, would not have made possible an effective averting of the Japanese attack, although both Short and Kimmel would have had time to get some of their anti-aircraft armament in shape for action and Short might have got more of his planes off the ground by the time the Japanese bombers arrived, thus increasing the damage to the Japanese. But let us stick to the approximately four hours that Short and Kimmel would have had in which to take action if Stark and/or Marshall had sent clear warnings to them by around 9:30 on the morning of the 7th. According to Hiles:

It would have required only four hours at the most for the Pacific fleet that remained at Pearl Harbor on the morning of the 7th to sortie from the harbor, and still less time for Short to have re-oriented his planes and anti-aircraft defense against the attack. Kimmel could have sortied and dispersed his entire force and perhaps rendezvoused with the three main task forces later on, but most likely he would have kept his ships dispersed until he learned the composition of the attacking force. After this, it is problematic as to just what he would have done. Admiral Kimmel has told me that he is not sure just what action he would have taken. Two American carriers against six for the Japanese might have been too great a risk to take, although the battle of Midway was won in June, 1942, against a much superior Japanese naval force and the four Japanese carriers were mainly destroyed by one American carrier, the Enterprise.

Now let me set the stage for you, assuming a four-hour alert. It would have been 3:30 A.M. at Hawaii. It would have been dark and would remain so for several hours. There would have been no need to wait and recall the liberty section which was ashore. The ships could always function with the duty sections in an emergency. Long before daylight all the major units would have been clear of the harbor and well scattered beyond visual distance. A few of the smaller ships might have been visible by the time the Japs arrived but even this is not likely because a large part of the fleet was already away with Halsey, Newton and Brown, and four hours would have been adequate for the depleted fleet to have sortied and dispersed.

It is safe to say that the Japanese would have found both the horizon and the harbor empty. This also presupposes that Nagumo would not have been alerted by Japanese spies in Honolulu as to the sortie during these four hours and withheld the attack, even have got ready to turn back to Japan. Several scouting planes preceded the attack waves to report back to Nagumo as to the state of the fleet and it is unlikely that Nagumo would have ordered an attack on an empty harbor.

Let us assume, however, that the bombing planes did proceed to Pearl Harbor and found nothing there. The targets were gone and well scattered out over the broad Pacific. The Japanese planes had no spare fuel to go flying around completely blind, looking for targets they knew not where; as it was, some of them ran out of fuel before they got back to their carriers after the attack. With this unexpected denouement, Genda and Fuchida (the Japanese bombing commanders) would have had no other choice than to recall the planes or bomb the off-shore installations and the shops, machinery and oil, which is not very likely under the circumstances. And up to this point we have assumed perfect conditions for Fuchida and have ignored the fact that Short and Martin would also have had that same four-hour warning and that their planes would have been in the air and the anti-aircraft guns ready to greet the bombers.

It is well to have this authoritative and detailed portrayal of what might have happened at Pearl Harbor and Fort Shafter on the morning of December 7th if Stark and Marshall had sent warnings to Hawaii by or before 9:30-10:00 Washington time.

Of course, Commander Hiles is assuming that all would have worked out smoothly if the warning had been received about 3:30 A.M. on the morning of the 7th, but how a situation looks on paper may be quite different from how it will take shape in action. It would have been quite a shock to officers, crews and soldiers to have been rudely awakened at 3:30 A.M. with the news that Oahu was about to be shattered by a Japanese bomber attack when there had been no previous warning of any such move and nearly every one in the armed forces there had been convinced that Japan would not make war on the United States, a rich and powerful country that no small island empire could hope to overcome.

Events might have worked out as Commander Hiles has indicated. On the other hand, there might have been much confusion, with the ships not all out of sight when the Japanese bombers arrived. The channel leading out of Pearl Harbor was so shallow that the battleships had to move slowly, and in the haste and confusion one of them might have run aground and made it impossible for ships behind it to reach the open sea. But it is certainly true that, if a clear warning had reached Fort Shafter and Pearl Harbor between 3:00 and 4:00 on the morning of the 7th, the Army and Navy forces and equipment on Oahu would have suffered smaller loss than occurred, unless Kimmel’s battleships had been sunk in deep water as the Repulse and Prince of Wales were shortly afterward in the southwest Pacific.

It is, of course, utterly abhorrent to have to conceive of Kimmel’s being subjected, as a result of Washington neglect or treachery, to any such shock and crisis as being warned of a Japanese attack at 3:30 on the morning of the 7th, when he could and should have been effectively warned days, weeks or months before, and there would not have been any Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

The main reason for deploring overemphasis on the failure to send last minute warnings is that this obscures and confuses the real nature and the extent of the guilt for failing to warn Hawaii in plenty of time. There was every reason for sending a clear warning there on November 27th, and any delay after December 4th was nothing less than criminal neglect, if one wished to save the American forces at Pearl Harbor. If one limits main consideration of the warning period to the late night of the 6th and the morning of the 7th, the Blackout and Blurout writers can conjure up all sorts of confusing alibis about timing and the possible disastrous results of warnings sent at this late hour, but there is no such way to counter or explain the failure to warn the Hawaiian commanders at any time during the previous nine days, or even as far back as when the first Bomb Plot message was decoded and read on October 9th. Nor was there any excuse for having failed to provide Pearl Harbor and Fort Shafter with a Purple Machine to intercept, decode and read the Japanese diplomatic messages right there, thus learning of the danger on the spot.

It is also futile and misleading to exaggerate the minor acts of incompetence or mis-judgment at Pearl Harbor between very early morning on the 7th and the attack at 7:50, so much stressed by Roberta Wohlstetter at the beginning of her book on Pearl Harbor. Such were the failure properly to interpret the discovery of a Japanese scouting submarine right off Pearl Harbor on the early morning of the 7th, the apparent indifference shown by Lieutenant Kermit Tyler of the Army Air Corps to the report from the Army radar station about some strange approaching planes, which might have been thought to be those of Admiral Halsey who was returning with his task force from Wake or the approaching B-17’s, and the official closing down of this radar station at 7:00 on the morning of the 7th, as had been ordered, but was not actually closed. These have some curious interest as minor deficiencies and mistakes of judgment, greatly bolstered by the impact of hindsight, but they had little to do with the approach, diverting or repulse of the Japanese bombing planes, which were already well on their way from their carriers to attack Pearl Harbor.