AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

Excerpted from Clarke, The Philosophical Approach to God: A New Thomistic Perspective, Second Revised Edition, New York: Fordham University Press, 2007, Part Three, second (unnumbered) section, “Is God Creator of the Universe? Whitehead’s Position,” 101-107.

“What then is the ultimate source or explanation of the unity of the universe, of why its two correlative poles, God and the multiplicity of the world, are attuned to each other so as to make up a single system, since neither one ultimately derives all its being from the other? . . . . Whitehead has turned our metaphysical clocks back not only to a pre-Christian but to a pre-Neoplatonic position, thus cancelling out one of the most decisive metaphysical steps forward in Western thought.”

I have given this excerpt its title. For related insights, see Peter A. Bertocci, “Creatio Ex Nihilo: ‘Not So Utterly Indefensible’” on this site.

Anthony Flood

April 4, 2010

Metaphysical Difficulties in Process Theology

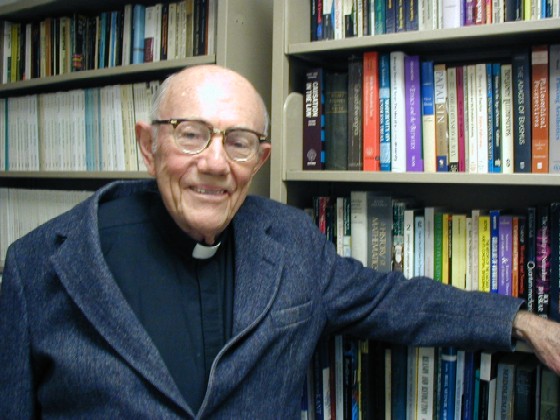

W. Norris Clarke, S.J.

In addition to being incompatible with traditional Christian belief in God as creator, Whitehead’s rejection of an initial creation of the world out of nothing runs into serious metaphysical difficulties. On the one hand, as we have said above, it brings us back to an older Platonic primal dualism of God against the world (in the latter’s aspect of primal raw material or multiplicity to be brought from chaos into order), where neither of these two primal poles is ultimately responsible for the other. What then is the ultimate source or explanation of the unity of the universe, of why its two correlative poles, God and the multiplicity of the world, are attuned to each other so as to make up a single system, since neither one ultimately derives all its being from the other? If there is to be any ultimate source of unity in the universe at all—which is dubious, just as it was for Plato—it seems to be pushed back beyond even God to an inscrutable, faceless, amorphous force of creativity which is just there, everywhere in the universe, as a primal fact with no further explanation possible—a kind of generalized necessity of nature, with striking similarities to the ancient Greek ananke. It should be remembered, too, that creativity for Whitehead is not an actuality in and for itself, but only a generalized abstract description of what is a matter of fact instantiated in every actual occasion of the universe. Creativity seems to be an ultimate primordial many, with no unifying source.

But not only is this doctrine in any of its forms not a Christian one, it also suffers from all the irreparable deficiencies of any ultimate dualism or multiplicity not rooted in the prior unity of creative mind. This lacuna in Plato was quickly recognized by the post-Platonic schools of Neoplatonism, culminating in the great synthesis of Plotinus, who considered himself as only completing the unfinished business of Plato by his doctrine of emanation of all reality from the One, including matter itself. Whitehead has turned our metaphysical clocks back not only to a pre-Christian but to a pre-Neoplatonic position, thus cancelling out one of the most decisive metaphysical steps forward in Western thought.

Even aside from the question of how to ground the unity of the system of the universe, with its two intrinsically correlated poles, God and the world, there remains another difficulty: if all creativity does not ultimately derive from God, why does this creativity continue to spring forth endlessly and inexhaustibly, all over the universe, in each new actual occasion, from no actually existing source? For creativity is not, as Lewis Ford insists, an actuality in and of itself, but merely a generalized description of the primal fact that it does spring up in each new actual occasion. It is not itself a source because it is not in itself an already existing concrete actuality. Hence the individual bursts of self-creativity which characterize each newly arising actual entity, and which are the only ground or referent for the term “creativity,” seem literally to emerge out of nothing insofar as their actual existence (= becoming) is concerned, with no prior ground for their actuality whatsoever—though there is prior ground for their formal elements. Why this creativity should bubble up unfailingly and inexhaustibly all over the universe through endless time, with no active causal influx or gift of actuality from another already existing actual entity, remains a total enigma—one that is not simply a mystery to us at present, but in principle rebuffs any further penetration by intelligence, since there is no more ultimate ground.17

Lewis Ford, one of the most representative Process thinkers in America, has responded to this objection by stating that once this first step is granted everything else falls into place, and that this is the most one can ask of an initial metaphysical principle. It seems to me, however, that the price of this initial enigma is too high. The doctrine of creativity is admittedly obscure and undeveloped in Whitehead. But until this difficulty is cleared up, the process theory of God remains both theologically and philosophically inadequate to express either the traditional Christian conception of God as creator—i.e., Ultimate Source of the very existence of the universe, as well as of its intelligible structures—or the metaphysical exigencies of an ultimate ground for the unity of the universe. An infinitely fragmented force of creativity cannot be an authentic ultimate, precisely because it is actually a many, and only abstractly one.

(To his great credit, however, in his later years, after the first edition of this book, Lewis Ford has suggested that a creative adaptation of Whitehead can be and should be made, according to which God becomes the ultimate Source of all creativity, which he then actively shares with all other beings. This would go far towards healing one of the basic gaps in the internal unity of the system.)

We find ourselves here in the presence of what seems to many of us the most radical metaphysical opposition between Whitehead and St. Thomas—and, it seems to me, on St. Thomas’s side, most of the great metaphysicians in history, both Eastern and Western. In St. Thomas there is an absolute priority of the One over the many, so that the many is unqualifiedly derivative from and dependent on the One, in an asymmetrical relation. In Whitehead, there is in the last analysis an original priority if the many over the One.18 No matter how much Whiteheadians may insist that the One brings into unity the many—that the One and the many are intrinsically correlative to each other, so that neither is prior to the other—it remains unalterable that the unity of synthesis is a later or secondary ontological moment (not necessarily temporal).

The original or primordial ontological contribution of each side of the correlation of God and world is radically and ultimately independent of the other. God is not responsible for there being a many at all—i.e., the basic “raw material” for there being a world to be brought into order at all. He is not even responsible for its primordial potentiality to be ordered; nor, obviously, is the world responsible for there being a God with the power to order it. This is true even in the primordial nature of God with respect to the infinite set of “eternal objects” or formal pattern-models of order and value which He eternally envisages and draws upon to lure the world into harmony, like the Platonic Demiurge which Whitehead takes as his explicit inspiration. Though the determinate ordering of these pure formal ideal possibilities is due to His creative initiative, still the primordial presence of some quasi-indeterminate reservoir of not yet integrated formal possibilities is not itself generated by the divine creative act but—vague and obscure as its status is in Whitehead—remains an ultimate given of independent origin even for the divine mind and power.19

Though this ultimate reservoir of the many in the order of forms does not possess full actual existence as actual entities, still they possess some kind of primordial being of their own as their own contribution of raw material for the act of divine ordering into a determinate world of possibilities. Again the many has radical priority, since the duality of God and world, God and possibles, is itself an ultimate original many. Thus there is no explanation finally of why both sides of this correlation are originally present at all, nor (another serious difficulty often overlooked) is there any reason given why there should be a positive affinity of one for the other—i.e., a positive aptitude or intrinsic capacity in one to be ordered by the other. Thus neither the original presence or givenness of the two sides of the correlation One/many (God/world) nor their intrinsic tendency and capacity to mutual correlation is given any explanation or ground. The many—at least in the sense of this initial duality of component terms—retains absolute priority, grounded in no prior or deeper unity.

But practically all of the great metaphysicians of the past, East and West, except Plato and Aristotle, have agreed on at least this: that every many must ultimately be grounded in some more primordial and ultimate One. A many makes no sense at all unless there is some common ground or property (existence, goodness, actuality, creativity) shared by each, without which they could not be compared or correlated at all. Nor can any many be intrinsically oriented toward order and synthesis unless some ultimate unitary/ordering mind first creatively thought up within itself this primordial correlation and affinity and implanted it in the many from one source. Not only all actual order, but all ultimate possibility of order must be grounded in a One, and in a Mind. As St. Thomas often put it, following the ancient “Platonic way” (via Platonica), “Wherever there is a many possessing some one real common property, there must be some one ultimate source for what the many hold in common; for it cannot be because things are many (not one) that they share something one.”20 Thus either we leave the many and its correlation with the One ultimately ungrounded, with no attempt at intelligible explanation at all, or else we must have recourse to some further hidden ultimate principle of unity. But this would require for Whitehead recourse either to some ultimate inscrutable principle of blind necessity or to some further God hidden behind his God—hardly Whitehead’s cup of tea.

In sum, despite Lewis Ford’s insistence that the primordiality of the many as co-equal with the One is one of Whitehead’s unique new contributions to modern metaphysics,21 the fact that it is new does not make it viable. In the last analysis, what is missing from Whiteheadian metaphysics is that it remains content with Plato’s Demiurge without pushing on to the underlying doctrine of the One or the Good, which Plato himself finally saw had to be the last word and which Plotinus carried all the way to its implicit consequences—the origin of matter from the One.

I am delighted, however, to learn that in these later years, after the publication of the first edition of the present book, Lewis Ford has been more and more willing to concede that creativity is not simply an independent force on its own, but may be said to be an original gift from God to all other beings, thus strengthening the unitary source of the universe. This would be a significant step toward healing the original unreduced dualism of the system and open a more fruitful dialogue with traditional Thomistic metaphysics.

Notes

17 Cf. Edward Pols, Whitehead’s Metaphysics: A Critical Assessment (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, 1967), 131.

18 Cf. David Schindler, “Creativity as Ultimate: Reflections on Actuality in Whitehead, Aquinas, Aristotle,” International Philosophical Quarterly 13 (1973): 161-71; and “Whitehead’s Challenge to Thomism on the Problem of God: The Metaphysical Issues,” International Philosophical Quarterly 19 (1979). The point of the latter article is that for St. Thomas the ultimate common attribute that unites all things, the act of existence (esse), is grounded in one actual, concrete source (God), in which it is found subsistent in all its purity and plenitude and from which it flows by participation to all other instances, whereas for Whitehead the ultimate unifying property, creativity, is never found condensed and concretized in one ultimate source, but remains always radically multiple, dispersed among many. See also the important article of Robert Neville, “Whitehead on the One and the Many,” Southern Journal of Philosophy 7 (1969-70): 387-93.

19 Process and Reality, 392: “God does not create eternal objects; for his nature requires them in the same degree that they require him. . . . This is an exemplification of the coherence of the categorical types of existence.” Cf. Leclerc, Whitehead’s Metaphysics, 199; cf. also Kenneth Thompson, Whitehead’s Philosophy of Religion, 127: “God does not bring creativity into being. . . . Neither does God bring pure possibilities into being. Pure possibilities are named ‘eternal objects’ precisely because they are uncreated.”

20 On the Power of God, question 3, article 5; cf. Summa Theologiae, Part I, question 44, article 1; Part I, question 65, article 1.

21 Lewis Ford, loc. cit., in note 11. [i.e., “The Immutable God and Fr. Clarke,” New Scholasticism 49 (1975): 191.