AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From Whose Togas I Dangle

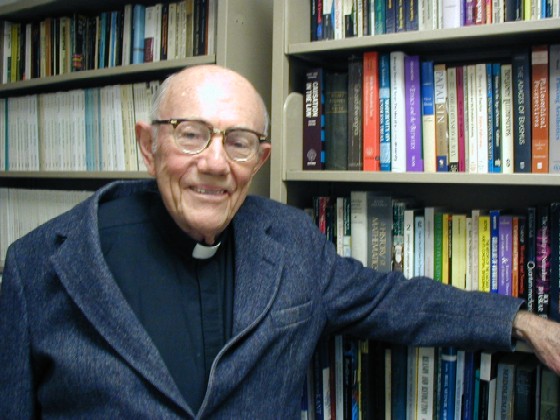

W. Norris Clarke, S.J.

June 1, 1915-June 10, 2008

The writings of the late Father W. Norris Clarke, an appreciative and engaging critic of Whitehead and Hartshorne, has forced me to rethink my under-standing of St. Thomas. I spoke with him briefly by phone in the early '90s when I was working my way through David Braine's The Reality of Time and the Existence of God, which Clarke had reviewed for The International Philosophical Quarterly. Remembering many years later the cheerfulness and energy with which he took that call from a stranger, I regret I did not keep in touch. Fortunately, all of his major papers have been anthologized. In addition to several that have meant a great deal to me, I will hunt down and format for posting nonanthologized articles and reviews. What I have done so far is listed below.

Anthony Flood

May 22, 2010

On Professor Niebuhr’s Paper, “On the Nature of Faith” [1961]

On Professor Tillich’s Paper, “The Meaning and Justification of Religious Symbols” [1961]

Analogy and the Meaningfulness of Language about God: A Reply to Kai Nielsen [1976]

The Problem of the Reality and Multiplicity of Divine Ideas in Christian Neoplatonism [1982]

The Metaphysics of Religious Art: Reflections on a Text of St. Thomas Aquinas [1983]

Charles Hartshorne’s Philosophy of God: A Thomistic Critique [1990]

The Compatibility of Receptivity and Pure Act: Reply to Steven Long [1997]

Metaphysics as Mediator between Revelation and the Natural Sciences [2001]

Clarke’s Journey: In His Own Words

I started off as a convinced Thomist from my first philosophical training with the French Jesuits at Jersey, under the guidance of the brilliant young Thomistic metaphysician, Andre Marc, from whom I developed a keen appreciation of the basic metaphy-sical structure of the real according to the vision of St. Thomas. Also decisive was my private reading of Joseph Marechal’s whole history of Western thought, Point de depart de la metaphysique, culminating in his seminal Vol. V on Aquinas himself, in which he stressed the innate dynamism of the human intellect toward the Infinite Fullness of being as the ultimate foundation of all human inquiry; added to this was my underground reading of the then temporarily banned Blondel’s Action (1st edition, 1893—better than all the later more cautious revisions), which powerfully highlighted the complementary dynamism of the human will toward the same fullness of being as good. I have always held onto these two fundamen-tal insights of St. Thomas as the basic for all human inquiry and search for the good, but I am not a full card-carrying member of the Transcendental Thom-ism school, for various technical reasons regarding whether and how they reached fully existential being as the basis of metaphysics by their method.

The historically important rediscovery of the pro-foundly existential character of St. Thomas’s meta-physics, centered on the act of existence (esse) as the fountainhead of all perfection, both in creatures and in God, diversified by various modes of limiting essence, was just getting under way when I was at Jersey (1936-39), under the dramatic leadership of Etienne Gilson in the 5th edition of Le Thomisme, but I took full explicit possession of this deeply inte-grating insight into Aquinas’s thought during my M.A. in philosophy at Fordham, under the direction of Anton Pegis, disciple and colleague of Gilson at Toronto. So I became what soon became known as an “existential Thomist.”

The next significant phase of my philosophical development came during my Ph.D. studies at Louvain, under the well-known Thomists Van Steen-berghen and De Raeymaeker. Here I shared in the exciting rediscovery of the central role of Neopla-tonic participation in the metaphysics of Thomas, especially as the basic structure behind the relation of creatures to God, going far beyond what he could get from Aristotle alone—all this from my reading and discussions with Geiger, Fabro, De Finance, etc. Now I came to understand St. Thomas’s entire meta-physical system as an original synthesis of Aristo-telianism and Neoplatonism. I wrote my thesis pre-cisely on the development of this synthesis in Thomas (summarized in the first, widely circulated article in my list of publications) a theme not yet widely known, it seems, in American Catholic Thom-istic circles.

The last key element in my philosophical forma-tion I picked up also during my doctorate at Louvain. All around me were blossoming the new movements of phenomenology, both the older more austere school of strict Husserlian phenomenology, which interested me less than the newer more existential interpersonalist phenomenologies of thinkers like Emmanuel Mounier, Martin Buber, Gabriel Marcel, Maurice Nedoncelle, John Macmurray, etc., and to a lesser extent Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger. I plunged deeply into them for months, before returning to St. Thomas for my dissertation. I saw the need now for both these approaches as complemen-tary to give us a more fully rounded understanding of the real. The interpersonal phenomenologies need the ontological grounding of dynamic substance or nature as a unified center for its many relations and its self-identity through time; Thomistic metaphysics needs to enrich the data it is seeking to explain by the more detailed concrete descriptions of the actual life of real persons provided so richly by phenomeno-logy. A creative synthesis was needed. This I have tried to outline in Person and Being (l993), now in its fifth printing, and my widely circulated article, “To Be Is to Be Substance-in-Relation” (1992), which sur-prised many non-Thomists.

In doing this I identify myself with the growing, late 20th century movement called “Personalist Thomism.” One leading center of this has been the Lublin School of Thomism (Poland), of which the best-known representative is Karol Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II), with his seminal book, The Acting Person and other similar writings.