AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

At the fourth meeting of the New York University Institute of Philosophy in 1960, Father Clarke contributed critiques of fellow symposiasts, Paul Ziff, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Paul Tillich. Sidney Hook, who organized the symposium, edited the proceedings for publication in 1961 as Religious Experience and Truth: A Symposium, New York University Press, arranging Clarke’s critiques as three sections of Chapter 28, “On Professors Ziff, Niebuhr, and Tillich” (224-230). The following remarks on a paper by Paul Ziff appear on pages 224-226.

Anthony Flood

May 10, 2010

On Professor Ziff’s Paper, “About ‘God’”

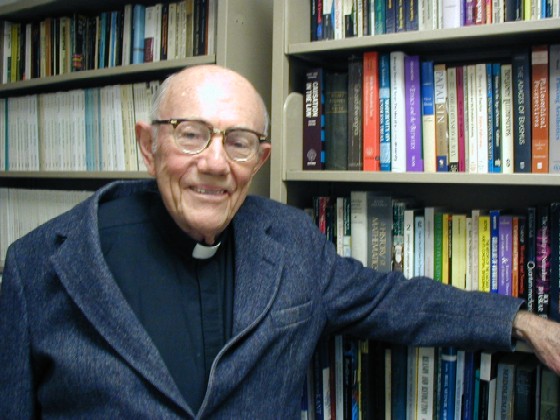

W. Norris Clarke, S.J.

One of the special merits of Professor Ziff’s paper, and even more, of his remarks in the discussion, was his care in not closing off prematurely the possibility of meaningful discourse about God by adducing oversimplified linguistic impasses of all sorts, as has so frequently been done by other analytic philoso-phers. In so doing he has rendered a distinct service to philosophical maturity and refinement of concepts in dealing with this difficult problem.

There are two criticisms, however, which I should still like to make concerning his position as expressed in the paper. The first concerns how the term “God” functions in religious discourse. (I accept his distinc-tion between religious language and religious dis-course as exact and well-taken for the English lan-guage.) For Professor Ziff, it functions as a proper name, and, therefore, presumably not as a descrip-tion. In the case of other ordinary terms in the language, one must indeed choose between these two uses. But it is just one of the unusual features of this most unusual of terms, “God,” that it combines the two functions indissolubly. In would say that, in view of its actual use down the ages in Western reli-gious discourse (monotheistic for many centuries), it functions primarily as a description; but, since one of the notes of the description is that it can be verified by only one referent (“God” means the one infinite Creator of all other things), this particular descriptive term can also be, and traditionally has been, used as a direct form of address or as a proper name. Some-thing of the same thing has happened in the case of terms like “Love,” “Truth,” etc. though not in so firm-ly crystallized a manner as with “God” (it could hap-pen also with a term like “Sun”), so that one can or could say in the direct address of prayer: “O Love,” “O Truth,” (or O Sun”), like “O God.” In the case of “God,” it seems to me that any adequate analysis of the role played by the term must indissolubly join these two uses: description and proper name.

The second point concerns section 23 [of Pro-fessor Ziff’s paper], on the impossibility of the plain man’s conception of God being compatible with the requirements for omnipotence. “It is a tenet of pre-sent physical theory that no physical object can at-tain a velocity greater than the speed of light. Con-sequently, according to present physical theory, no being has it in its power to transport a stone from the earth to the sun in one second. But this is to say that no omnipotent being exists. Hence, according to present physical theory, nothing answering to the plain man’s conception of God exists.”

The difficulty here is that the requirements laid down for omnipotence applied to actions in the physical world contain a hidden analytical contra-diction, which rules out a priori any possible meaning or verification for the term “omnipotence.” Such a contradiction does not exist, however, either in the conception of the genuine “plain man,” nor in that of the careful theologian or theistic philosopher. In effect, the conditions laid down by Professor Ziff come to this: God could not transport a stone a certain distance both according to the laws of an Einsteinian universe (which He himself, according to the supposition, has freely set up and freely maintains) and at the same time in contradiction to those same laws. Obviously He could not, since it would involve His simultaneous ratification and violation of the same laws with respect to the same object. But I believe it is quite easy to show that not only the theologian, but even more the plain man, understands omnipotence in such a context as signifying the power of God to suspend or change at will the physical laws He himself has set up, in order to effectuate some good. In other words, a physical impossibility is always a conditioned one, the condi-tion being the continued free willing of the present system of physical laws by God—a condition revocable by the same will; a logical or metaphysical impossibility would alone be an unconditioned one, whose violation would be impossible even to God and would involve no genuine limitation in order of real being or real perfection, since it would imply the positing of an internally contradictory nonbeing.