AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From Graceful Reason: Essays in Ancient and Medi-eval Philosophy Presented to Joseph Owens, CSSR, ed. Lloyd P. Gerson. Papers in Mediaeval Studies 4 (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1983), pp. 301-314.

Anthony Flood

May 10, 2010

The Metaphysics of Religious Art: Reflections on a Text of St. Thomas Aquinas

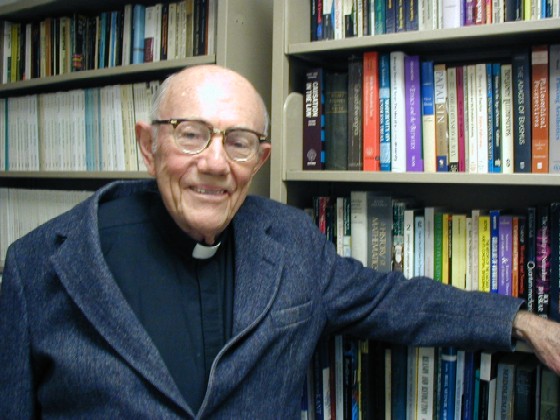

W. Norris Clarke, S.J.

The purpose of this essay is to draw out the impli-cations hidden in a single brief text of St. Thomas (Summa theologiae 1. q. 84. a. 7) for understanding the metaphysical and epistemological structures latent in religious art. I came rather suddenly to the realization of these implications one day when I was travelling in India and was studying a splendid bronze sculpture of Shiva, the dancing God, with eight arms—somewhat a challenge, at first, to our ordinary Western artistic sensibilities. I would like to share with my readers my reflections on that day, as a sample of what seems to me the ever-fresh fecundity of the philosophical thought of St. Thomas as applied to areas outside of philosophy itself. This is my humble way of joining in this tribute to Father Joseph Owens, whose life-work has also been dedicated so long and fruitfully to the unfolding of the riches hidden within the texts of St. Thomas.

A brief preliminary clarification as to what I mean by “religious art.” I am taking the position—contro-versial, perhaps—that there is a distinctively religi-ous character to certain works of art that is somehow intrinsic to them, and not merely due to the extrinsic accident that they are inserted in a religious setting or even illustrating some religious subject matter. Thus the mere fact that a painting—let us grant a good one in itself—depicts a mother lovingly holding a child and carries the title “Madonna” does not make it automatically a piece of religious art. There must be something within the painting itself which gives expression to the religious dimension. Perhaps the simplest way to define or identify this characteristic, so as to apply to all the religious traditions of mankind, whether they use the name “God” or not for the Ultimate Reality they are in quest of, is to describe it as a thrust toward Transcendence, a reaching beyond the ordinary, all too painfully limited level of our human lives toward a higher, more ulti-mate dimension of reality freed from these limita-tions. In a word, it is the reaching out of the finite toward the Infinite, expressed through finite sensible symbols. I take it that the symbol, in this rich con-text of psychology, art, and religion, may be aptly described as man’s ever unfinished effort to express in form what is beyond all form and expression.1 The challenge—and the genius—of authentic religious art is therefore to succeed somehow in giving effective symbolic expression to this thrust toward Trans-cendence. I am not going to argue here that such authentic and distinctively recognizable religious art exists. The striking examples of it in many religious cultures seem to me sufficient evidence for the fact. My effort here will be focused toward uncovering the hidden metaphysical and epistemological structure behind such art.

The text of St Thomas which I wish to unpack is the famous one on the dependence of all our human thinking on the imagination as a springboard; this dependence in turn is the expression in the cognitive life of the deeper metaphysical union of soul and body to form a single per se unity, the unified being that is man. This text is from the Summa theologiae, Part 1, Question 84, Article 7, first the body of the article, which lays out the foundational doctrine, and then more specifically the Reply to Objection 3, which applies this general doctrine to how we know higher, purely spiritual beings, in particular God. Let me first quote the text of the article:

I answer that, in the state of the present life, in which the soul is united to a corruptible body, it is impossible for our intellect to understand anything actually, except by turning to phantasms. And of this there are two indications. First of all because the intellect, being a power that does not make use of a corporeal organ, would in no way be hindered by the lesion of a corporeal organ, if there were not required for its act the act of some power that does make use of a corporeal organ. Now sense, imagination and the other powers belonging to the sensitive part make use of a corporeal organ. Therefore it is clear that for the intellect to understand actually, not only when it acquires new knowledge but also when it uses knowledge already acquired, there is need for the act of the imagination and of the other powers. For when the act of the imagination is hindered by a lesion of the corporeal organ, for instance, in the case of frenzy, or when the act of the memory is hindered, as in the case of lethargy, we see that a man is hindered from understanding actually even those things of which he had a previous knowledge. Secondly, anyone can experience this of himself, that when he tries to understand something, he forms phantasms to serve him by way of examples, in which as it were he examines what he is desirous of understanding. For this reason it is that when we wish to help someone to understand something, we lay examples before him from which he can form phantasms for the purpose of understanding.

Now the reason for this is that the power of knowledge is proportioned to the thing known. Therefore the proper object of the angelic intellect, which is entirely separate from a body, is an intelligible substance separate from a body. Whereas the proper object of the human intellect, which is united to a body, is the quiddity or nature existing in corporeal matter; and it is through these natures of visible things that it rises to a certain knowledge of things invisible. Now it belongs to such a nature to exist in some individual, and this cannot be apart from corporeal matter; for instance, it belongs to the nature of a stone to be in an individual stone, and to the nature of a horse to be in an individual horse, and so forth. Therefore the nature of a stone or any material thing cannot be known completely and truly, except inasmuch as it is known as existing in the individual. Now we apprehend the individual through the sense and the imagination. And therefore, for the intellect to understand actually its proper object, it must of necessity turn to the phantasms in order to perceive the universal nature existing in the individual. But if the proper object of our intellect were a separate form, or if, as the Platonists say, the natures of sensible things subsisted apart from the individual, there would be no need for the intellect to turn to the phantasms whenever it understands.

Objection 3: There are no phantasms of incorporeal things, for the imagination does not transcend space and time. If therefore our intellect cannot actually understand anything actually without turning to the phantasms, it follows that it cannot understand anything incorporeal. Which is clearly false, for we understand truth, and God, and the angels.

Reply to Objection 3: Incorporeal beings, of which there are no phantasms, are known to us by comparison with sensible bodies of which there are phantasms. Thus we understand truth by considering a thing in which we see the truth; and God, as Dionysius says, we know as cause, by way of excess, and by way of remotion. Other incorporeal substances we know, in the state of the present life, only by way of remotion or by some comparison to corporeal things. Hence, when we understand something about these beings, we need to turn to the phantasms of bodies, although there are no phantasms of these beings themselves.2

The body of the article expresses the classic teaching of St. Thomas on the necessary collabora-tion between intellect and sense knowledge (either the external senses or the imagination) for all natural acts of understanding in a human subject. I stress “natural” in order to leave open the possibility of various modes of supernatural infused knowledge which could bypass the senses. I also stress “understanding” in order to leave open the possibility of some directly intuitive acts of knowledge (whether natural or supernatural), such as the intuition of one’s own self as conscious active presence. Any conceptual understanding of the nature of this self would involve the cooperation of sense and abstractive intellect. The cognitional theory itself is grounded, as St. Thomas clearly points out, in the metaphysical per se unity of soul and body to form a single being. All this is too well known to need any further commentary here by me.3

Our special interest in this article is twofold: first, the way in which such a mode of knowing tied to imagination can come to know purely spiritual beings, in particular God, of which there can be no sense image. This is by way of introduction. Our second and primary focus of interest is in how this way of knowing is reflected in religious art. The Reply to Objection 3 contains in very condensed form the essence of St. Thomas’ teaching on how a human knower can come to know God, a purely spiritual and infinite being, through the collaboration of sense and intellect. This doctrine is also well known, but let me summarize it briefly.4

I. The Mind’s Ascent to God

St. Thomas insists that we have no direct intellectual understanding of God’s being as it is in itself. We must always begin with the knowledge of the sensible world, and then allow ourselves to be “led by the hand,” as he puts it elsewhere,5 by ma-terial things, in a dialectical process of “comparison with sensible things,” as he says in our present text, all the way up to an indirect knowledge of God as ultimate cause, with all the attributes appropriate for such a cause.

It is hard for us to appreciate today what a revolutionary stand that was in St. Thomas’ own time. The common doctrine of the dominant Augustinian school before him and in his own time (e.g., St. Bonaventure) had by the mid-thirteenth century assimilated the new Aristotelian technical theory of knowledge by abstraction from the senses with respect to the material world around us, since St. Augustine’s illumination theory was focused more on necessary and eternal truths or judgments and had little to say about the formation of concepts about the material world. This Aristotelian “face of the soul,” as they put it, looked down, as it were, on the material world around it and abstracted the forms of sensible things from matter. But there was also a second, definitely higher and more noble, face of the soul, more directly illumined by God, which looked directly up to know spiritual things, such as one’s own soul, angels, God, eternal truths, etc.6

St. Thomas resolutely rejected this doctrine of two natural faces of the soul, one looking down into the world of matter, the other looking directly up into the world of spirit.7 The structure of our natural human knowledge is far more humble, he believed. There is only the one face of the soul, which is turned directly only toward the material cosmos around it as presented through the senses. Then, by the application of the basic inner dynamism of the mind, its radical and unrestricted exigency for intelligibi-lity—which can be expressed as the first dynamic principle of knowledge: the principle of the intelligi-bility of being, “omne ens est verum”8—we can step by step trace back the intelligibility of this material world to its only ultimate sufficient reason, a single infinite spiritual Cause that is God. Man is the lowest and humblest of the spirits, whose destiny it is to make his way in a spiritual journey through the material world back to his ultimate Source and his own ultimate home.

What is the general structure of this ascent of the mind to God from the sensible world? It passes along the classic “Triple Way” first outlined by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and adapted to his own use by St. Thomas9–as well as by many other thirteenth-century Christian thinkers. St. Thomas refers to it very tersely in our present text when he says that we know God “as cause, and by way of excess, and by way of remotion.” We first discover God as ultimate cause of all material and finite beings, since no material being in particular, and no finite being in general, can be the sufficient reason for its own existence. What more can we say about this First Cause? Here the Triple Way of Pseudo-Dionysius enters in more explicitly: (1) the way of positive affirmation of divine perfections grounded in the causal relation; (2) the way of negation or “remotion,” when we remove from what we have affirmed any limit or imperfection; and then (3) the way of reaffirmation of the perfection in question by expanding it to an infinite degree. This final stage, St. Thomas calls the ways of “excess,” a somewhat pale translation of the Latin excessus, which means a “going out of itself” by the mind in a movement beyond all finites toward the Transcendent.

The first step of affirmation based on causality rests on the principle that every effect must in some way, at least analogously, resemble its cause, since all that is in the effect—as effect—as must come from its cause, and a cause cannot give what it does not possess in any way, at least in some equivalent higher mode of perfection. Hence we can affirm that whatever positive perfection we find in creatures must have its counterpart, either in an equal or in some higher analogous equivalent mode, in the cause.

The second step, that of negation or remotion, purifies what can be affirmed of God in a proper and literal mode of speech (opposed to a metaphorical mode). Since God is pure spirit and infinite in perfection, we cannot affirm literally and properly of Him any perfection which contains within its very meaning some note of imperfection or limitation. This eliminates at once a whole class of attributes or predicates which can be applied literally to material beings or finite creatures but not to infinite pure spirit. Thus we cannot argue that because God is the Cause of the perfection of eyesight in creatures, therefore He has infinitely good eyesight; for eyesight implies the built in limitation of matter and finitude. A rather small number of basic attributes remains which describe perfections which we first find exemplified in creatures in a limited way, but which contain no imperfection or limitation in their meaning. That is, they are purely positive unqualified perfections, values which we must judge to deserve our unqualified approval, to be unqualifiedly better to have than not to have. Such are, for example, existence, unity, goodness, beauty, activity, power, intelligence, will, love, etc. These alone can be affirmed positively and properly of God, not metaphorically. But they too must first be purified of any imperfection or limitation we find attached to them in creatures.

Once we have thus purified them by “removing” all traces of imperfection and limitation, we can then, in the third step, reaffirm them of God, adding the index of infinity. Here the mind leaps beyond what it can directly represent or conceive in a clear concept, and, borne aloft by what Plato called “the wings” or “eros” of the soul, i.e., the radical drive of the spirit toward the total intelligibility and goodness of being, projects out the positive content of the perfection it is affirming, along an ascending scale of analogy, to assert that this perfection must be found in infinite fullness in God, though the mind cannot directly see or clearly conceive just what this fullness is like in itself. This movement of the mind beyond all finite beings, and hence all clear concepts, is called in our text “the way of excess,” that is, the mind’s going out of itself (ex-cedere) beyond all finite concepts.

II. Application to Religious Art

Now let us apply this basic movement or ascent of the mind toward God to the domain of religious art. How does the work of art succeed in its own way in leading us through sensible symbols to make this leap beyond all sensible symbols toward the Infinite which they symbolize, that is itself beyond all form and symbol? Let us first note that the general structure of the two movements is strikingly similar. Both must start from sense images. And both must make a final leap beyond images and concepts toward a Transcendent Infinite beyond all images and concepts. The way of passing from the first step to the last differs in each. The philosophical ascent follows a purely interior path of intellectual analysis, insight, argument, etc. The work of religious art, on the other hand, must somehow stimulate, through the very medium of sensible symbols themselves, the leap of the mind and heart to what is beyond them. How can the work of religious art pull off this remarkable feat of leading its viewer (or hearer) beyond itself, beyond even the entire world of symbols and matter? It seems to me that the process follows very closely the triple path outlined in our present text, in the Reply to Objection 3: (1) comparison, (2) remotion, (3) élan toward the Transcendent.

The first step corresponds to St. Thomas’ “com-parison with sensible things.” It selects some sen-sible symbolic structure which suggests some posi-tive similitude, however distant, to the Transcendent reality the artist is trying to express. Thus he can lay out symbols of power, majesty, wisdom, love, etc. as found in our world.

The second step corresponds to the “remotion” or purification stage in St. Thomas’ Triple Way. Here the artist must suggest the radical difference between his sensible symbol, taken literally, and the Beyond he is trying to express through it. This is equivalent to the removal of limitation and finitude from our concepts in the philosophical ascent. The artist expresses it by introducing a note of strangeness or dissimilitude of some kind into the primary similitude he has first laid down, in order to indicate that what he is pointing to is far different from, and higher than, the original sensible springboard from which he started.

There are many ways an artist of genius can do this, some crude and simple and obvious, such as the lifting of a human figure above the earth, encircling it with a halo of light, etc. Or it can be in some striking creative way that breaks the mold of the ordinary, jolting the viewer into the awareness that the work of art is pointing beyond this dimension of ordinary experience. Such, for example, are the Hindu statues of Shiva, Creator and Destroyer of worlds, portrayed as a dancer with six, eight, ten arms. Since the upraised hand and arm is a sign of power, a human figure with six arms breaks through our accustomed images and evokes a power beyond that of ordinary humans. It is a similitude shot through with dissimilitude, at once a comparison with sensible things of our experience and a negation of them in their present limited state, or, to turn to Byzantine Christian art, consider the great icons, which sometimes seem so strange to us in the West, in part because we do not understand what the artist is trying to accomplish. An icon of Mary, the Mother of God, for example, will first exhibit a positive similitude with the human figure of a Woman. But if we examine the face we notice a strange unearthly, fixed, and apparently empty stare in the eyes, unlike any ordinary human look. This is the negative moment, the affirmation of dissimilitude, which stimulates us to recognize that she is looking with the eyes of the soul beyond our material world directly into timeless eternity, into the world of the spirit and the divine, beyond change and motion.

There are an inexhaustible number of other, sometimes infinitely subtle and sophisticated, ways in which an artist of genius can suggest this negative moment of breaking the similitude with our world: e.g., the elongated figures of the saints in El Greco, the monumental, often frightening masks of African ritual art, the cone emerging from the top of the head in statues of the Buddha, etc. If this dimension of negativity, of purification from the limitations of our world is not present in some way in a work of art, it may indeed be good art, but cannot, it seems to me, qualify as properly religious art. It remains too stuck in the world of our ordinary human reality to help us spread the wings of the soul and soar toward the Transcendent. This criterion can lead us, I think, to disqualify as religious art many famous paintings and sculptures labelled “Madonnas,” both in our own and in earlier times—including not a few by renowned Renaissance artists, such as Raphael himself. The absorption of these Renaissance artists in particular in exploiting to, the full the new realism of the human form effectively stifles, all too often, any élan toward the Transcendent. We remain absorbed in the natural beauty of womanhood and childhood in themselves.

The third step, the élan toward the Transcendent beyond the merely human and the finite, is really only the other side of the previous stage and so closely woven into it as to allow only conceptual abstraction from it. This is the most mysterious aspect of a work of religious art, where the individual genius of the artist comes most to the fore—a genius often eluding explicit analysis. Somehow, by the dialectical opposition and complementarity of the two preceding, positive and negative steps the artist must stimulate our minds, hearts, and feelings, set them resonating in depth, so that they will be spontaneously inspired to take off from the natural, the this worldly, the material, and the finite to reach out on the wings of the spirit toward the transcen-dent Mystery of the Infinite, the divine. Great religious art has an uncanny power to draw us thus out of ourselves, to help us to take off and leave behind both ourselves and the work of art. Thus it is the express aim of Hindu religious music, for exam-ple, to draw the listener slowly. through the quality of the music, into a meditative state, which gradually deepens so that the listener is drawn beyond himself into communion with the Transcendent and forgets all about the music. All the examples, we gave previously as illustrations of the negative moment are also examples, through the very dynamism inherent in the expression of this negative moment, of how religious art can stimulate the élan of the spirit toward the Infinite: the statue of the dancing Shiva, the great Byanztine icons, the paintings of El Greco, the African ceremonial masks, etc. So too the reverent contemplation of certain statues of the Buddha, if one follows carefully the continuous rip-pling folds of his garments, can have a quasi-psychedelic effect and draw one deep into contem-plation. So too the Tibetan Buddhist paintings, which are carefully designed as meditation guides. So too the Pietá of Michelangelo, by its deeply moving expression of the meditative silence of Our Lady, draws us into her own contemplation of her son, as God-man and Savior of the world through His Passion.

One of the most obvious and striking examples, one deeply familiar to St. Thomas himself, is the medieval Gothic cathedral, Chartres, for instance, whose soaring élan of incredibly attenuated, almost dematerialized, stone columns and arches, suffused with light from the sun beyond the structure itself, admirably symbolizes the soaring of the human spirit in adoration and prayer toward the transcendent God, the Light of all finite minds, who “dwells in light inaccessible.”10

What is happening way in all these instances is that the artist has found a way through his symbolism to tap into and trigger off the great underlying, ever present, but ordinarily latent dynamism of the human spirit toward the Infinite. Thus stimulated, the simmering coals of this immense underground longing of the spirit suddenly flame up into consciousness and, using the symbol as a springboard, leap out toward the hidden Magnet that draws them. Just how the artist succeeds in doing this is his own secret, and often the secret of a whole tradition, once the initial geniuses have found the way. But it seems that the individual artist must himself experience this soaring of the spirit in order to charge his symbols with the power to do this for others. The work of a lesser artist, who either has not had the personal experience of this élan of the spirit, or who has not found the way to incarnate it effectively in sensible symbols, just will not stimulate the viewer (or hearer) to take off on the wings of his own spirit, but will leave him earthbound, stuck in the finite, the thisworldly. His artwork may be good art in itself, but not good religious art. Too much so-called religious art is of this earthbound quality.

It should be noted that the sensible symbols themselves are not capable of directly imaging or representing the Transcendent in the fullness of it own reality, any more than our philosophical concepts, and in fact less so. Their power comes from their ability to set resonating the underlying dynamism of the human spirit toward the Infinite and offer it a channel (perhaps, to change the metaphor, we might say a lightning rod) through which it can flash into consciousness, and thus allow our integral human consciousness, mind, heart, and will, to soar for a moment toward the Transcendent Magnet that draws it secretly all the time, the Good in which all finite goods participate, the Ultimate Final Cause that draws us implicitly through all limited particular final causes. This radical dynamism of the human spirit toward the Infinite is the dynamic a priori of the human spirit, constitutive of the very nature of finite spirit. But the human spirit, in order to pass from the state of latent active potency, just under the level of consciousness, to actuality on the conscious level, needs to be triggered by some initial reference to the world of sense and imagination, since the human act of knowledge is the act of the whole human being, soul and body together.

Once triggered off by the sensible image, this dynamism of the spirit can use the latter as a springboard to reach out toward the Transcendent in two main ways: (1) in a purely intellectual way by the use of abstract analogous philosophical concepts, or (2) in a more total existential way, by the use of sense images as symbols which set resonating the integral psychic structure of man, mind, will, imagination, emotion—or, if you will, to use the synthetic term preferred by the oriental tradition, the entire “heart” of man. The intellectual path of concepts points more accurately and explicitly toward the Infinite as infinite. But because these concepts are so abstract and imprecise, they move only the mind. The path of the sensible symbol, on the other hand, is much vaguer and less explicit on the intellectual level, but by its much richer evocative power it sets resonating the whole psyche (including the body in which it is so deeply rooted), and thus tends to draw the whole person into existential communion with the symbolized that it points to. The aim of the abstract concept (or, more accurately, on the judgment in which the concept is imbedded) is to lead us toward deeper intellectual comprehension of the Transcendent Mystery; the aim of the artistic symbol is to lead us into deeper existential communion with this same Mystery. Both ways are needed, and complement each other; neither can supplant the other.

The last point to note in our discussion of the text of St. Thomas is his interesting addition about our mode of knowing purely spiritual beings, which are higher than ourselves but still finite. St. Thomas says that because they are not the efficient cause of our material cosmos or ourselves we cannot use the path of causal similitude, the first of the Three Ways by which we come to know God. Hence we can know them, he says only “by comparison or remotion.” He does not not even mention here the excess us or élan of the mind. This seems to suggest that it is in fact easier to come to know God and something about his nature than to know angels. This is certainly true with respect to our first coming to know of the existence of angels compared to knowing the existence of God. Since they are not the cause of our universe, it is not possible to make a firm argument that they must exist under pain of rendering our universe unintelligible, as one can do for the existence of God in the Thomistic perspective. One has to learn of the existence of angels (both good and bad) either through some Revelation, which we accept on faith, or by some merely suasive argument (such as that they are needed to complete the harmony of the universe as expression of God).

Does this inferiority of our knowledge of the existence of angels compared to our knowledge of the existence of God hold also for an understanding of their nature? St. Thomas does not tell us here. But one might make the case that this position could be defended, since our knowledge of God contains one added note of precision that cannot be applied to any finite spirit, namely, that God is the infinite fullness of all perfection and situated very precisely at the apex of all reality and value for us. Thus it is easier for our concepts about God, joined with the pointing index of infinity, to tap into the underlying dynamism of the human spirit toward the Infinite and stimulate the inner leap of the spirit (excessus) toward its ultimate Source and Goal. It would then follow, if we transfer this argument to the sphere of religious art, that it would be in principle easier to create a work of art symbolizing God (or at least our relation to God) than one symbolizing angels. Interesting thesis! and one that contains not a little truth.

However, we do find in fact that the symbolic representation of higher spiritual beings (e.g., angels, both good and evil) is common in religious art, not only in the Christian but in other traditions as well. And the experience of the viewer, including the leap of the mind beyond the sensible symbol, seems to be very similar to the experience of religious art referring directly to God himself. So I would prefer to fit it in to the same basic structure outlined above, using not the causal similitude between God and creature but the doctrine of participation of all finite beings in the unitary perfection of God. Since all finite beings, both material and spiritual, proceed from the same ultimate Source, and every effect must to some degree resemble its cause, it follows that all of them must participate in some analogous way in the basic transcendental perfections of God, such as existence, unity, activity, power, goodness, beauty, etc. This immediately posits a bond of analogical similitude between all creatures, reaching in an ascending hierarchy of being from the lowest material being all the way up to Infinite Spirit. Furthermore all intellectual beings share a bond of analogous similitude in the order of spirit, both with God and each other. It follows that in a work of art, through the dialectical interplay of comparison and remotion, similitude and dissimilitude, the dynamism of our spirit can be stimulated to leap beyond the sensible symbol toward something higher and better than ourselves, along the way of God, along the ascending ladder of being towards its infinite apex, hence worthy of our profound reverence. The attractive power of the higher, precisely because it leads along the path of participated goodness towards the infinite goodness of the Source, can trigger the élan of the spirit to soar beyond our present level of incarnate spirit towards the realm of pure finite spirit, even though this be only a finite participation in Infinite Spirit, which alone is the ultimate Magnet activating the entire life of our minds and wills and enabling them to transcend their own level.

III. Conclusion

Our aim has been to follow the lead of St. Thomas in uncovering the underlying metaphysical and epistemological structures supporting the ability of authentic religious art to give symbolic expression to the Transcendent and our relation to it. The epistemological structure is based on St. Thomas’ distinctive theory of human understanding as a synthesis of sense and intellect, according to which any act of the intellect must first find footing in some image of the senses or the imagination and then use it as a springboard to go beyond the sense world, either to the formal essence of the sensible thing itself or to its cause. The ascent of the mind to know God takes place through a triple process of (1) causal similitude, (2) negation of all imperfections and limits, i.e., negation of exact or univocal similitude, and (3) reaffirmation of the purified perfection together with a projection of it toward infinite fullness, accomplished by a burst into consciousness of the radical unrestricted drive of the human spirit toward the Infinite—a drive that is constitutive of the very nature of finite spirit as such. This élan or excessus of spirit enables it to leap beyond its own level and all finite beings to point obscurely through the very awareness of its own dynamism (the pondus animae meae of St. Augustine) toward the Infinite. The metaphysical underpinnings of this theory of knowledge are (1) the integral union of body and soul to form a single being with a single unified field of consciousness; (2) the radical drive of the spirit (intellect and will) toward the Infinite as ultimate Final Cause; and (3) the doctrine of creation, ex-plained in terms of participation and causal simili-tude, which grounds a bond of analogical similitude not only of all creatures with God but also of all creatures with each other.

The inner dynamism of the authentically religious work of art follows the same path of ascent. It must first put forth a positive symbolic expression of some similitude with the Transcendent, then partially negate this similitude, by introducing some element of strangeness or dissimilitude with our ordinary experience on a finite material level. The dialectical interplay of similitude and dissimilitude must then be artfully contrived so that by its very structure it taps into and awakens the ever present but latent dynamism toward the Infinite that lies at the very root of all finite spirit, so that our spirit takes wings and soars in an élan or excessus (a going out of itself) reaching beyond the sensible symbol toward lived communion of the integral human being with the Transcendent Reality it is trying to express. The genius of the artist consists in his ability to give symbolic expression to dissimilitude within similitude in such a way as to set resonating the deep innate longing within us all for the Transcendent, so that the work of art finally leads us beyond itself in a self-transcending movement, “dying that we might live” more deeply—an analogue of the loss of self in order to find the true self characteristic of all authentic religious living. To sum it up in St. Thomas’ own extraordinarily terse but pregnant terms: compara-tio, remotio, excessus.

1 For a good explanation of the meaning of symbol and its role in religious experience and worship, see Thomas Fawcett, The Symbolic Language of Religion (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1971).

2 Translation by Anton Pegis: Basic Writings of St. Thomas Aquinas (New York: Random House. 1944), I: 808-810.

3 The entire book by Karl Rahner—Spirit in the World, trans. William Dych (New York: Herder and Herder, 1968)—is an extended commentary on this one article of St. Thomas. Although we do not agree with all the details of the author’s interpretation of St. Thomas, his exposition of the main point of the text—the dependence of all man’s knowing on the senses as a starting point—is very rich and illuminating.

4 For a convenient reference, see my The Philoso-phical Approach to God (Winston-Salem: Wake Forest University Publications. 1980), chapter 2: The Metaphysical Ascent to God.

5 Cf. ST I. q. 12. art. 12; I. q. 43. art. 7: “Now the nature of man requires that he be led by the hand to the invisible by visible things (ut per visibilia ad invi-sibilia manuducatur).”

6 For the medieval Franciscan doctrine of the two faces of the soul as proposed by St. Bonaventure, see E. Gilson, History of Christian Philosophy in the Middle Ages (New York: Random House. 1955), p. 336.

7 Cf. Quaestiones disputatae de anima, art. 17, my translation: “For it is manifest that the human soul united to the body has, because of its union with the body, its face turned toward what is beneath it: hence it is not brought to fulfillment except by what it receives from these lower things, namely by forms (species) abstracted from phantasms. Hence it cannot arrive at the knowledge either of itself or of other things except insofar as it is led by the hand by these abstracted forms.”

8 This notion of the radical unrestricted dynamism of the human spirit toward the unlimited horizon of being and ultimately to the Infinite itself as the fullness and source of all being is clearly in St. Thomas, in his doctrine of the natural desire for the beatific vision, but it has been highlighted as the foundation for all metaphysics and natural theology by the Transcendental Thomist School, e.g., Maré-chal, Rahner, Lonergan, etc. For a convenient expo-sition see my Philosophical Approach to God, chapter 1: The Turn to the Inner Way in Contemporary Thomism.

9 Cf. ST 1, q. 12, art. 12, and elsewhere.

10 Cf. O. von Simpson, The Gothic Cathedral (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956), chapters 3-4.