AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

At the fourth meeting of the New York University Institute of Philosophy in 1960, Father Clarke contributed critiques of fellow symposiasts, Paul Ziff, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Paul Tillich. Sidney Hook, who organized the symposium, edited the proceedings for publication in 1961 as Religious Experience and Truth: A Symposium, New York University Press, arranging Clarke’s critiques as three sections of Chapter 28, “On Professors Ziff, Niebuhr, and Tillich” (224-230). The following remarks on a paper by Reinhold Niebuhr appear on pages 226-227.

Anthony Flood

May 10, 2010

On Professor Tillich’s Paper, “The Meaning and Justification of Religious Symbols”

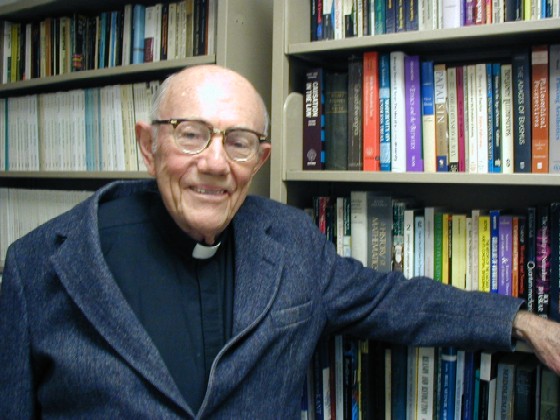

W. Norris Clarke, S.J.

Since we did not have available the text of the paper actually given by Professor Tillich, I must trust my memory in commenting on the gist of what was said, using as a guide his previously published paper on the subject. (The latter paper, by the way, I found to be an extraordinarily rich, profound, and illumin-ating—and one with which I could agree to a very large extent. As he understands symbolic language, I do not think there is as much difference or oppo-sition as he would seem to think between it and ana-logical language as I understand it. A Catholic theo-logian, Father Gustave Weigel, who knows the thought of Professor Tillich well, is now using the term “symbolic language” more and more as a syno-nym for “analogical language,” and did so, in fact, throughout his own paper at this same gathering.)

The one point I would like to comment on is Professor Tillich’s fear that analogy applied to God is “too static” and his attempts to fix and hold in a finite concept the ineffable and utterly transcendent nature of God. I would like to link this with the constant difficulty voiced by logicians, philosophers of science, linguistic analysts, and others during the symposium: by what right can we take terms from ordinary ex-perience and language—which all the theistic philo-sophers and theologians agree must be done—and apply them with a significant shift and extension of meaning to something, God, which we cannot directly experience (unless we are mystics—and then we cannot communicate literally what we have experi-enced)? Must not the new elements introduced into the concepts when applied beyond our own experi-ence be necessarily a blank of positive meaning, a pure shot in the dark?

This is a genuine and profound problem, the main problem in the philosophy of religion, one might well say. I have time here to point out only what seems to me the key notion which permits a working out of the solution. The objectors commonly presume that what is going on is this: we take a term which has one definite conceptual content as drawn from and applied to our own experience, then when we apply it to God, we add on to it a new element which is quite extraneous to the latter and whose meaning we cannot possibly understand from this experience. If this were the case, we would indeed have made an illegitimate conceptual and linguistic leap.

But the whole point of the application of analogy to God is that the extra dimension of content intro-duced into the concepts thus applied is not dragged in arbitrarily from outside what we discern in our experience. It is rather a dynamic exigency, a thrust, a direction, already imbedded deep in the intelligible texture of the finite world of our own ex-perience. As we confront the world with reflective intelligence, the profound and ineluctable exigencies of our intellect and will for total and unconditioned truth, being, goodness, perfection, etc. help us to discern in the finite, imperfect beings of our ex-perience their radical state of deficiency or imper-fection, both in the possession of the perfections they manifest as well as in their incapacity to satisfy the exigencies built into our intellectual nature.

The notion of limited and deficient perfection is here the operative one that acts as a springboard to point the mind beyond its present experience. Found within the beings of our experience, it yet, by the very dynamism that constitutes its intelligibility, points beyond itself to a mysterious source which is pure, simple, unconditioned, hence infinite, plenitude of what we experience here as “only so much and no more,” i.e., as radically deficient, limited, and unsa-tisfying. We do not properly look away from the finite to find the Infinite. We rather find the exigency for the infinite written right into the intelligible texture of the finite recognized as such, and we find it by looking more deeply into the finite itself.

Note that I am not arguing the point here whether or not one can construct a valid proof of the real existence of the Infinite from the finite, though I believe that with care one can. I am making only this point: the meaningfulness of our language and thought about the Infinite finds its support in the profound human experience of discerning within our world the latter’s intrinsic character of radical limitation, deficiency, and inability to satisfy our own deepest exigencies of intellect and will. And the notion of deficient or limited goodness is, by its very inner structure, both psychologically and conceptual-ly, a highly dynamic one which necessarily and importunately points beyond itself to a mysterious plenitude in the same line, affirmable—thought not representable—in the dim mirror of need, desire, and hope.

Therefore, analogous language which is combined with the peculiar “pointing-concept” of infinity, what we might analogously call the “infinity-operator”—and only such language can be legitimately applied to God—contains within itself all the dynamism of the negative theology whose need Professor Tillich has so clearly seen, and this precisely because it includes within its very meaning-structure the expression of the mind’s own act of transcending all possible finite experience.

It may still be objected that, however, we have no positive idea of what, for example, a beyond-finite, or beyond-human, love might be; it might no longer be love at all but something quite different. The answer here is two-fold. First, through the causal argument to the dependence of the finite on an infinite Source, combined with reflection on our own exigencies of intellect and will, we can say this much with certainty about what we call “infinite Love”: it cannot fall below the core of positive perfection, goodness, being, etc. which we have found in the finite participant within our experience, but must be at least all of that and could be, still better, incal-culably more. In other words, when we apply the attribute love to God we are using it, not as a “ceiling-concept” limiting its content to what our experience of love is, but as a “floor-concept,” so to speak, indicating at least all this positive value and whatever else is better, as long as it does not negate or evacuate the positive content of the authentic value we have experienced in human love. Secondly, we must be careful before applying any concept of God (intrinsic analogy applies not only to terms but to their conceptual content) to see if it can sustain “purification” from imperfection or limit as an essential and irreducible part of its meaning. Thus love would meet this test, not sexual love; so would intellectual knowledge, but not knowledge by inference, and so forth. I trust this may help somewhat to show how sense can be made out of analogical language applied to God.