AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

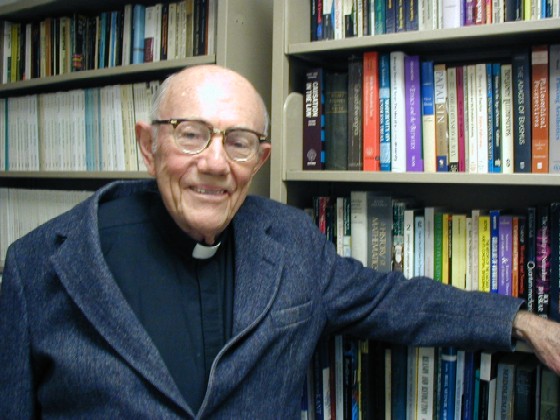

From Neoplatonism and Christian Thought, Dominic J. O’Meara, ed., International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Norfolk, Virginia, 1982, 109-258. Scanned from booklet given me by the later Father Clarke sometime in the early ‘90s. (It consisted of a small-font facsimile of the book’s chapter, preceded by its editor’s preface.)

Anthony Flood

April 14, 2010

The Problem of the Reality and Multiplicity of Divine Ideas in Christian Neoplatonism

W. Norris Clarke, S.J.

My purpose in this paper is to trace a chapter in the history of ideas within the broad stream of Neoplatonism as it passes into Christian thought. The theme is one that caused special difficulties to Christian thinkers as they tried to adapt the old wine of Neoplatonic metaphysics to the new wineskins of Christian theism. My intention is not to focus in detail on just what each thinker involved held, as a matter primarily of historical scholarship. My interest will rather be focused primarily on the basic philosophical problem itself, and on tracing out the general types of solutions tried out by various key thinkers along the line from Plato to Saint Thomas. The problem is this: For Plato and all pre-Christian Platonists the world of ideas was “the really real”; hence, the multiplicity of the ideas’ and their mutual distinctions were also real, though in the mutual togetherness proper to all spiritual reality. Such multiplicity, however, was not admitted into the highest Principle, the supreme One, who by nature had to be absolutely simple to be absolutely one. But the Christian God, as personally knowing and loving all creatures and exercising providence over every individual, had to contain this world of archetypal ideas within his own mind, in the Logos. Yet the real being of God was also held to be infinite and simple; the only real multiplicity allowed within it was that of the relational distinction of the three Persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. How would it be possible to put all these doctrines together without internal contradiction in a consistent doctrine of God? The story of the various efforts to meet the problem is a fascinating and illuminating study in the history of ideas. Let us retrace the principle moments in it.

Plato

For Plato himself it is clear that the world of ideas possesses a strong dose of reality. The breakthrough to discover the abiding presence of this transcendent dimension of reality, for the first time in the history of Western thought, must have been a powerful, almost intoxicating, experience for him, as though a veil had been pulled aside to reveal at last the splendor of the truly real, in comparison with which our changing world of sensible objects was only a shadowlike imperfect image. No modern neo-Kantian or analytic philosophy reinterpretation of the theory of ideas as merely conceptual or linguistic categories should be allowed to vitiate the strength of Plato’s ontological commitment to the objective reality of ideas, however this be finally interpreted.1 But when we come to the relation between the world of ideas and the mind as knowing them, clouds of ambiguity begin to thicken. Where are the ideas? What is their ontological “location” or ground? Do they constitute an independent dimension of reality on their own, whose autonomous light is then passively received by any mind knowing them? Or do they reside in some ultimate mind that supports them by always thinking about them?

With respect to the human mind it is clear that the world of ideas constitutes a realm that is ontolo-gically quite independent of our minds. We do not just make them up; our knowledge is true because they are there. The matter is more obscure when we come to the demiurge of the Timaeus. No direct statement is made; but the images used suggest that the demiurge, in order to create an ordered cosmos, contemplates and copies an objective world of ideas that is already given even for him; it is the natural object of his contemplation, as it is for all the gods and unfallen souls who drive their chariots across the eternal heaven of ideas, but it is not something they think up or produce out of their own substance but which they gaze on as already given. Contemplation, the highest act of any Platonic mind, is a motionless reception, not a productive act.2

This leaves the ultimate status and ground of the world of ideas veiled in obscurity for Plato. The sparsely adumbrated doctrine of the One and the Good as the ultimate source for both ideas and minds does significantly complete the picture. But it is never made clear whether the Good is a mind or something above it, whatever that might mean. There are indeed highly significant hints in the Timaeus and the Sophist that the whole world of ideas is part of a single great living unity. But the generation of the world of ideas by the Good, even if conceived as ultimate mind, which Plato never calls it, is quite compatible with the objective reality and the multiplicity of this world as the really real. In any case, the ultimate relation between the world of ideas and mind remains unfinished business in Plato, a legacy for his successors to unravel.

Plotinus

When we come to Plotinus—I will pass over the intermediate preparatory stages of Middle Platon-ism—a major resolution of the problem has been achieved, but with serious internal tensions still re-maining. On the one hand, the ideas are now firmly located ontologically within the divine Nous; they no longer float in ambiguous ontological independence, but are eternally thought by this eternal mind as its connatural object. As a result the ideas themselves, though immutable, immaterial, and eternal, are alive with the very life of the divine Mind itself, each one a unique, self-thinking, spiritual perspective on the whole of reality.

On the other hand, there still remains a strong dose of the old Platonic realism of ideas, and this creates a tension between two somewhat conflicting perspectives on the status of the ideas in Plotinus—a tension that it does not seem to me that he com-pletely resolves. This tension concerns the relation of priority between the Nous and the ideas: Is the Nous absolutely prior in nature (not, of course, in time) to the ideas, the realm of authentic being, as generative act to its product? Or do the ideas have a certain priority over the Nous as the true existence over the act that contemplates it? Or is there simultaneous reciprocal dependence, inherence, or even identity without any priority at all?

We would be tempted at first, viewing the problem from within the central dynamic perspective of the descending flow of emanation from the One, to assert that obviously the Nous (or Intellectual Principle) has priority over the realm of being or ideas, as their generating source. As the Nous, emanating from the One, turns back toward the One in its first ontological “moment,” as an empty and formless ocean of potentiality, it is fecundated, so to speak, by its contemplation of the splendor of the One and bursts forth into producing the whole multi-ple world of ideas in atemporal ordered sequence (corresponding to the inner order of the intelligible numbers, one, two, . . .).3 This dynamic perspective is certainly present in Plotinus, but surfaces only occasionally and briefly. I might add, speaking in my own name as a philosopher, that in this direction lies, it seems to me, the only satisfactory metaphysical explanation of the relation between mind and ideas: the absolute priority of mind, as ultimate spiritual agent, over all ideas; existential act must always precede idea. This perspective gradually became dominant in Neoplatonism, both Christian and Islamic, after Plotinus, and in most modern thought. But it is still a minor chord in Plotinus himself.

There is another and more prominent perspective in Plotinus, however, which runs through the whole gamut of his works, both early and late; here the old Platonic priority of being over intelligence still stubbornly holds on and is never explicitly negated by Plotinus. This can be found especially in Ennead V, 9, “The Intellectual Principle, the Ideas, and the Authentic Existent,” a very early treatise (no. 5) in chronological order. The first point developed here is that the ideas cannot be outside the Intellectual Principle, otherwise its truth would be insecure and its knowledge imperfect. The ideas must thus be part of the very self of the Nous, identical with its being as a single unitary life flowing through all the distinct parts. But Plotinus goes on to say more, giving a certain priority to the ideas over the Nous as thinking principle, so that they seem to constitute the very life of the Nous itself.

Being true knowledge, it actually is everything of which It takes cognizance; it carries as its own content the intellectual act and the intellectual object since it carries the Intellectual Principle which actually is the Primals and is always self-present and is in its nature an Act . . . but always self-gathered, the very Being of the collective total, not an extern creating things by the act of knowing them. Not by its thinking God does God come to be; not by its thinking Movement does movement arise. Hence it is an error to call the Ideas intellections in the sense that, upon an intellectual act in this Principle, one such idea or another is made to exist or exists. No: the object of this intellection must exist before the intellective act (must be the very content not the creation of the Intellectual Principle). How else could this Principle come to know it. . . .

If the Intellectual Principle were envisaged as preceding Being, it would at once become a Principle whose expression, its intellectual Act, achieves and engenders the Beings; but, since we are compelled to think of existence as preceding that which knows it, we can but think that the Beings are the actual content of the knowing principle and that the very act, the intellection, is inherent to the Beings, as fire stands equipped from the beginning with fire-act; in this conception the Beings contain the Intellectual Principle as one and the same with themselves, as their own activity. But Being is itself an activity; there is one activity, then, in both or, rather, both are one thing.4

The above presents a significantly different per-spective: here the inner being and act of the ideas seems to constitute the very act of the Nous itself, rather than the Nous giving them its own being by actively thinking them up. The older Platonic conception of mind, here faithfully reproduced, seems to be that mind as such, even the divine Mind, is by nature contemplative, not constitutive, of its object. This position, however, leaves open the difficulty we saw earlier in Plato, that is, what is the ultimate ground for the unified multiplicity of the world of ideas? It seems to be an exigency for intelligibility that only the active power of a unitary mind can ground both the multiple reality of the ideas and their mutual correlation into a single unified system. That is why the later more dynamic per-spective in Plotinus, that of the Nous as generative of the world of ideas, is more metaphysically satisfying, and is the one that actually dominated in the subsequent history of Neoplatonism.

Even though priority is occasionally given to Nous over the ideas, the strong realism of the ideas still remains undimmed in Plotinus. And it is this that forbids allowing the world of ideas to be in the One. Since the ideas are really real, true being, and really multiple or distinct, and the One as pure unity cannot tolerate the slightest shadow of multiplicity within itself, even that between mind and idea, the entire world of ideas or true being must be relegated to a lower level of divinity, the second hypostasis or Nous.5

The Early Christian Fathers

When the first philosophically minded and trained Christian thinkers took over the Neoplatonic philoso-phical framework to use in the intellectual explication of their faith, during the third and fourth centuries, they had to make two drastic changes in the matter which concerns us. First, the subordinationist hierarchy of divine hypostases in Plotinus had to be condensed into a single supreme divine principle, in which the three Persons within the divine nature were perfectly coequal in perfection of being, distinguished only by internal relations of origin, not by differing levels of perfection. Thus the Word or Logos, the Second Person, corresponding analogous-ly to Plotinus’ Nous, was declared perfectly coequal with the Father (corresponding analogously to Plotin-us’ One) sharing the identical divine nature and perf-ection. Secondly, the single supreme God of the Christians was identically creator of the universe through knowledge and free act of love, and exer-cised personal providence over each and every indi-vidual creature. This required that the one divine Mind, the same for all three Persons but attributed by special aptness to the Word or Logos, contain the distinct knowledge of every creature as well as the universal archetypal ideal patterns guiding the creation of the world according to reason. The old Platonic and Neoplatonic world of ideas, enriched with the distinct knowledge of individuals, is now incorporated directly into the one supreme divine nature itself. Christian thinkers simply had to do this to do justice to their own revelation, and they had no hesitation, but rather took pride, in doing so.

The metaphysical repercussions, however, of making the above changes in Neoplatonic tradition were of seismic proportions, and did not seem to be recognized very clearly for some time in their full philosophical implications. Two basic Neoplatonic axioms have now been violated. First, knowing a dis-tinct multiplicity of objects, even only as ideas, is no longer considered an inferior mode of being, wea-kening and compromising the radical purity of unqualified unity and simplicity in the One. To know multiplicity is no longer a weakness, but a positive perfection, part of the glory, of a One that is person-al. To know multiplicity is not to become multiple oneself. Secondly, purely relational multiplicity even within the real being or nature of the One is no longer a compromise or destruction of its unity, but an enrichment. The highest form of unity is now not aloneness but communion of Persons with one mind and will. We are not concerned here with this second principle, relational multiplicity within the nature of the One. Our concern is limited to the status of the world of ideas within the divine Mind.

It was one thing for Christian thinkers to assert that the world of ideas must be within the divine Mind as Logos, in order that God may personally know and love his creatures. But it is another thing to come to grips successfully with the metaphysical problems involved in thus adapting the Neoplatonic doctrine of the world of ideas. In particular, what about the strong realism of ideas as true being, the really real, which was so deeply ingrained in the whole Platonic tradition, no less, in fact even more, in Plotinus than in Plato himself? If the ideas remain, as always in this tradition, true and real being, they must also be really multiple. Does this not introduce an immense multiplicity of real beings, an immense real pluralism, within the very being of God himself, thus negating his infinite simplicity? In orthodox Christian doctrine, as it was gradually worked out, the only distinct realities allowed in God were relations, and the only real relations allowed were relations of origin resulting in the three Persons. But if all the divine ideas are also authentic, hence, real being, and at the same time distinct from each other in the intelligible (real) order, then there is not only a multiplicity of distinct real beings within God himself but a still greater multiplicity of real relations bet-ween them. For the relations between ideas are clearly distinctly intelligible, and for every traditional Platonist whatever is intelligible is also real.6

It is not clear to me that the Greek Fathers ever came to grips explicitly with this metaphysical problem of the reality of the divine ideas in God, aside from asserting that God knew them all with a single act of knowledge, which Plotinus would also admit. (I would be very happy to receive any information from my colleagues on this point, since patristics is not my field and I have not had the time in preparing this paper to do extensive study on this point.) My general impression is that we will have to wait till a later period to find explicit metaphysical discussion on this point.

Let us turn briefly to Saint Augustine in the West, as a prime example, it seems to me, of avoiding the issue. He holds simultaneously two metaphysical doctrines that I do not see that he has brought toge-ther in a consistent whole. On the one hand, one of his central doctrines, learned, as he tells us, from the Platonists, is that of divine exemplarism, namely, that the divine Mind contains the ideal exemplars, the rationes aeternae, of all created things, accord-ing to which he creates them by willing them to be, to be expressed, outside of himself as real creatures, as real essentiae.7 It should be noted along the way that Augustine is careful not to call the divine ideas essentiae aeternae, the eternal essences of things, but only rationes aeternae—eternal “reasons” or ex-emplary ideas, models. Since the concrete term ens, entia did not yet exist in Latin in Augustine’s time—it was introduced deliberately by Boethius centuries later—essentia was the standard noun derivative from the verb esse used in Augustine’s time for referring to existential being.8 Hence, on the one hand, one might be led to believe that these rationes aeternae were not considered by Augustine to be a realm of true being, in God, since the entire universe of real being was created in time freely, not from all eternity, as these rationes necessarily existed in the mind of God.

On the other hand, when Augustine comes to an explicit discussion and definition of what it means to be—to be a being—his criterion of true being is quite unambiguously the old Platonic one of immutability; to be is to be immutable, to be identically and immutably what one is. His texts could hardly be more forceful:

There is only one immutable substance or essence, which is God, to which being itself (ipsum esse), from which essence draws its name, belongs supremely and in all truth. For that which changes does not keep its very being, and that which is capable of changing, even if it does not change, is capable of not being what it was. There only remains, therefore, that which not only does not change but is even absolutely incapable of changing which we can truthfully and honestly speak of as a being.9

Being (esse) is the name for immutability (incommutabilitatis). For all that changes ceases to be what it was and begins to be what it was not. True being, authentic being, genuine being is not possessed save by that which does not change.10

Being (esse) refers to that which abides. Hence that which is said to be in the supreme and maximal way is so called because of its perdurance in itself.11

All change makes not to be what once was; therefore he truly is who is without change.12

The difficulty here for a Christian thinker is that this criterion for true being is verified perfectly by the divine ideas, as well as by God himself in his own being. The ideas in God are indeed eternal and immutable, as the ideal pattern for all creatures and the ground for all truth, which by its nature must be immutable. Since they perfectly verify the criterion, they should indeed be true being, real being for Augustine, just as they were for Plato and Plotinus, from whom the doctrine of divine ideas was directly inherited. Yet strangely enough, Augustine never quite seems to draw this conclusion and speak explicitly of the divine ideas as real being in themselves. He just seems to drop the point, to pull back into discreet silence just before he gets into metaphysical trouble. It is, however, common Augustinian doctrine that things are present more truly and nobly in the divine ideas of them than in their mutable, imperfect, created existence. Perhaps he did not see clearly the difficulty of the ideas as real multiplicity in God, as did Plotinus; or perhaps he did see it, but did not know quite what to do with it, and just quietly let it drop. At any rate, he gives us no clear philosophical principles by which to solve it.13

John Scottus Eriugena

Let us now skip to a later Christian Neoplatonist, the early medieval thinker John Scottus Eriugena, whose thought has the advantage for our purposes of bringing together both the Augustinian and the Dionysian traditions. Its special interest lies in that the problems that remained latent and untreated by Saint Augustine now come out into the open with striking sharpness in this daring but by no means always consistent thinker.

The point that concerns us is the ontological status of the second division of nature in the vast cosmic schema of John Scottus’ De Divisione Naturae, namely, natura creata et creans. This comprises the divine exemplary ideas or, as he calls them, the “primordial causes,” which are the “first creation” of God, coeternal with the divine Word, but always dependent on the Word, in whom they subsist. They are created but also creating in their turn, charged with the power to unfold and produce the whole material cosmos spread out in space and time.14

The first point to notice is the strong Platonic realism of this realm of creative ideas. This is the realm of true being below God (who, for John Scottus, is the superessential Source above being itself).15 It is in this ideal realm that all creatures, especially the sensible world of creation, have their true being, perfect and immutable; they are more real, they more truly exist, in these eternal idea-causes than in themselves as the explicated effects or emanations of these causes, for the latter are not merely abstract ideas or static models but causal forces charged with creative power of their own, though deriving, of course, from their higher Principle. Thus each one of us exists more truly in the eternal idea of man than in our own temporally spread out existence in this lower material world. We have here one of the strongest statements of what is to be a favorite theme of Christian Neoplatonists all through the Middle Ages, at least in the pre-Scholastic period.16

The realism of these primordial causes is also borne out by the assertion that they have been “made,” “formed,” “created” by God as the first level of creation—a stronger term than any previous Christian thinker had used to refer to the divine ideas, though, to do him justice, he sometimes warns that “created” here is not used in as strong and proper a meaning as its ordinary sense as applied to the second creation, that of the present contingent world. These primordial causes are produced by the Father in the Word from all eternity, in whom they subsist; yet as made (produced) they deserve to be called created. But what is created by God and which, itself, has causal power must certainly be real, and because immutable, also eternal, and spiritual, that is, authentic being, of which the changing world of bodies is but a shadowy image or participation. No statements of Augustine about the being of this realm of divine ideas are nearly as strong and clear as those found in John Scottus. It looks as though the Neoplatonic world of true being in the Nous has reappeared with new vigor and splendor.

It is a little surprising, therefore, to discover that, when Eriugena comes to speak of the mode of being of these primordial causes in the Word, with respect to their real multiplicity and distinction, he asserts in the strongest possible terms that in the divine Word they are absolutely “simple, one, unseparated,” perfectly identical with the Word’s own being, and “indistinguishable, without differentiae,” until they unfold in their actual effects in the space-time sensible world.17 To illustrate how they subsist in simply unity in the Word, he uses the example of how all numbers are present in the monad before division and how all lines are present in the point that is the center of a circle, with no distinction until they begin to unfold from the center.

Here I have the impression that Eriugena is being a better Christian than a Neoplatonist. I do not see how he can consistently hold both the real being and plurality of the primordial causes and also their perfect simplicity, unity, and identity with the Word as subsisting in it. Plotinus in fact holds the exact opposite, and would object as follows: The way that all numbers are in the number one and all lines in the point at the center of the circle is indeed the way that all things are precontained in the highest principle, the One, who is “the potentiality of all things” (dynamis pantōn) without being any of them. But this is not the way the ideas, the realm of true being, are in the second hypostasis, the Nous. There they are indeed held together in the unity of a single undivided spiritual life of intelligence; but this unity is a complex unity, not a simple one; it includes all the distinct intelligibilities of each Idea-Being as intelligibly distinct (though not separated or divided), as well as the distinction between the Nous as subject and the realm of being as intelligible object. It is precisely because of this multiplicity that the world of ideas can have no place in the perfect, simple unity of the One, but only in a lower, less unified hypostasis.18

But there seems to be no trace in Eriugena of these reservations about the perfect unity and simplicity of the primordial causes in the Word. It is not clear how he can have it both ways, though if he is to remain both a good Christian and a good Neoplatonist he must try. Here we have the latent tension between the conflicting demands of the two traditions coming sharply to a head, since Eriugena pushes each one all the way to the limit. It is a remarkable case of the coincidence of opposites. If one looks at this apparent impasse as a speculative philosopher, there seems to be only one possible way in which one could hold onto both sides of the opposition without contradiction, although this “solution” brings its own new train of problems with it. Suppose that one were to hold that true being, the very being of the primordial causes, is nothing else but their being thought by God. Their truth is identical with their being. In this case since the act of knowing or thinking them is one single simple act, and they have no other being save their being thought, it could be said that their being, as identical with the act of thinking in the Word and never really emanating out from it to possess their own distinct being—until, of course, they are unfolded in the material cosmos—is really one single simple being identical with the Word.

In fact, it seems that this is precisely what Eriugena himself has followed, at least in certain of his strong formulations, such as:

For the understanding of all things in God is the essence of all things . . . all things are precisely because they are foreknown. For the essence of all things is nothing but the knowledge of all things in the Divine Wisdom. For in Him we live and move and have our being. For, as St. Dionysius says, the knowledge of the things that are is the things that are.19

For the understanding of things is what things really are, in the words of St. Dionysius: “The knowledge of things that are is the things that are.”20

It is true that Eriugena does qualify this identity here and elsewhere by calling the divine knowledge the cause of the things that are, so that cause and effect would seem to be distinguished. But if this distinction is pushed too far, hardened into the strong Aristotelian real distinction between cause and effect—and I think this is also true in its own mitigated way in Neoplatonism—then his position on the unity, simplicity, and identity of the primordial causes in the Word will collapse. Only in the relation between thought and its self-generated ideas can there be a real identity of being between cause and effect, granted that the ideas have no being of their own.

I have two remarks to make about this doctrine of the identity of thought and being in Eriugena. First, if this is the case, it is now easy to understand how all creatures can be more truly in God, that is, in his knowledge, than in themselves, since it is this knowledge that in fact constitutes their true and perfect being. Another daring doctrine of Eriugena also becomes clear: in a sense, man himself is the creator of the material world, because he holds it together in unity in his own mind, as participating in the divine wisdom, and the material world exists more truly and perfectly even in man’s mind than in itself. Again true being is identical with being known. We are here on the edge, if not over the edge, of something like the Hegelian mode of idealism, as has often been pointed out. We will consider the philosophical difficulties of this position later.

Secondly, it seems to me that here Eriugena has gone farther than Plotinus and classic Neoplatonism itself, and in a sense dramatically reversed the old Platonic realism, which on the other hand he seems to be strongly asserting and certainly wishes to assert. For in the Plotinian Nous, or world of true being, as we have seen, even though the ideas are held together in the unity of a single unified spiritual life, the act of divine intelligence, still this life, this unity of the world of being and knowing, is a multiplex unity, an intelligible (hence, real) diversity in unity and unity in diversity. The ideas truly emanate from the Nous, while remaining within it, to the extent that they are distinguished as subject and object; also the ideas truly have being within them, so much so that it is almost equally legitimate to say that the Nous itself is constituted in being by its union with the ideas as to say that the ideas are constituted in being by the Nous—there is a kind of reciprocal priority between them; a strong dosage of the old Platonic realism of ideas as in themselves true being still remains. Nothing like this can be found in Eriugena. In no way can it be said that the Word for him is constituted by the ideas it eternally thinks. The relation of dependence is strictly one-way, asymmetrical. His solution is Christian; can it still be called authentically Neoplatonic? I doubt it.

Let us now turn briefly to some of the purely metaphysical difficulties inherent in the Neoplatonic side of Eriugena’s doctrine of the divine ideas as true being, with the result that we, like all creatures, exist more truly in our primordial idea-causes in God than in our own “explicated” temporal existence in our-selves—the third division of nature, that which is created but does not create. If this position is taken literally and in full seriousness, then the problem arises, What is the point of this unfolding of our true being, already present from all eternity in God, into our present lesser mode of existence? What is the point of our existential struggle for salvation in human history in a lesser mode of being when we are already perfect in our truest being in God? The whole value of human history, including that of the Incarnation and temporal life of Christ himself, seems to become so secondary and “accidental,” as he puts it, that it becomes disturbingly ambiguous, if not tinged with unreality. His only answer seems to be the classic Neoplatonic one, a purely impersonal kind of metaphysical law of emanation—that the emana-tion must go on to its furthest multiplicity, that the Craftsman of the universe would not have shown forth the fullness of his power unless he had made all that could be made and unfolded all the oppositions between creatures and not just their harmonies. It should be remembered that in the second division of nature, the primordial causes, there are no oppositions or differentiae between the various genera and species; all is perfect togetherness.

This is a typical Neoplatonic theme or axiom of emanation, that the great chain of being must unfold all the way to the limit of its possibilities, by an inherent necessity of the self-diffusiveness of the Good. But such a view of the value and meaning of the contingent world as only an inferior ontological state of the same world at a higher level is hardly compatible with the inspiration of Christian personal-ism, where the supreme locus of value is the existen-tial dimension of freely given personal love, moral nobility, and so on. The subject of the salvific redem-ption of Christ and the final beatific vision in the heavenly Jerusalem is not the eternally perfect, im-mutable idea of man, but the unique contingent indi-vidual John Smith who has worked out his salvation freely with the help of God on the stage of human history. In a word, there is a profound metaphysical, epistemological, and religious ambiguity in the Neoplatonic conception of the relation of the ideas to true being, not indeed in the presence of exemplary ideas of all things in God, but in their ontological evaluation, namely, that the true being of anything is found more fully, as true being, in its idea state in the mind of God than in itself. The classic Neoplatonic worldview of reality is not ultimately a personalism. The tension, if not contradiction, between this meta-physical view of reality and that implicit in any authentic Christian personalism seems to me to be profound and irreconcilable; it remains one of the central unsolved problems haunting Christian Neoplatonists—also, I might add, Islamic and Sufi Neoplatonists—throughout the pre-Scholastic Middle Ages. To sum it up, as this problem surfaces in John Scottus Eriugena, I do not think he can hold, if he is to be a consistent and authentically Christian thinker, both that the primordial causes are absolutely simple and one in the Word, which a Christian must hold, and that the true being of all creatures resides in these divine ideas, rather than in their own contingent being in history, which a traditional Neoplatonist should hold. One of these two positions will have to give way if a consistent Christian metaphysics is to develop. But for this we have to look beyond the daring and seminal, but not always consistent, brilliance of John Scottus Eriugena.

In thus casting doubts on the metaphysical consistency and Christian assimilability of the cher-ished Neoplatonlc theme that our true being is found in, consists in, the eternal idea of ourselves in the mind of God, I do not wish to deny the power and fruitfulness of the theme as it functioned—under-stood somewhat loosely, without pressing its meta-physical implications too rigorously—as a guide for spiritual development in the rich flowering of Chris-tian spirituality during the Middle Ages. The oper-ative concept here is that we understand our true self and come to realize it by turning toward and striving to fulfill the ideal model or exemplar of our fulfilled selves that God holds eternally to his mind and draws us toward by the magnetism of his goodness. Our true selves are indeed seen in God’s ideas of us, and this vision is pregnant with the magnetic drawing power of the Good. But this does not require the further metaphysical commitment that our true being, our true selves, literally is, consists in, the divine idea of us. But it took a long time for these underlying metaphysical issues to be worked out explicitly in medieval Christian thought.

The School of Chartres

Let us now move several centuries down the line and take a brief look at another Christian Neopla-tonist treatment of the same problem. This is the famous School of Chartres, known for its exaggerated Platonic realism of ideas.21 Its main themes are really a revival of John Scottus Eriugena with some original variations. The themes we are interested in are the realism of the divine ideas and their ontological status in the mind of God. Again we find almost the identical position of Eriugena. The true being of creatures is found in the divine ideas, which Thierry of Chartres, perhaps the most daring of the school, calls formae nativae. These are found in their pure state in the mind of God, and become imprisoned and diminished by union with matter. As Clarembald of Arras tells us, the true being of anything comes from its form: omne esse ex forma est . . . . quoniam forma perfectio rei et integritas est.22 But all these forms as in God become a single simple form; God is the forma essendi of all forms and through them of all things.23 But as they exist in God these exemplary forms are not yet explicated or unfolded as they are in the created world. Just as all numbers are already precontained in the simple unity of the monad or number one, so all forms are complicatae (enfolded as the opposite of unfolded) in the unity of one form in God. As Thierry puts it in a striking image, in God all forms fall back into the one: “The forms of all things, considered in the divine mind, are in a certain way one form, collapsed in some inexplicable way into the simplicity of the divine form.”24 And thus “every form without matter is God himself.”25

Clarembald of Arras explains further how the many forms are enfolded without real plurality in the one:

Every multitude lies hidden in the simplicity of unity, and when in the serial process of numeration a second is numbered after the one and a third after the second, then finally a certain form of plurality flowing from unity is recognized, and so without otherness there can be no plurality.26

Here again, it seems to me, we run into the same unresolved tension as we found in Eriugena. It is indeed an authentically Christian metaphysical doctrine that all ideas are identical in being with the one perfectly simple being of the divine Mind. But I submit that this is not an authentically Neoplatonic doctrine; the ideas in the divine Nous for all classic Neoplatonists are already unfolded in their distinct intelligible multiplicity and hence in their plurality of being, thus forming the system of true being as integrated plurality—a plurality, however, without spatial or temporal separation, held together in the unity-multiplicity whole of a single spiritual life. (It is indeed true—this was objected to me in the discussion of the paper—that the ideas, like all things, are in a sense in the One, as the “power of all things” [dynamis panton]. But this is in a mode of supereminent simplicity, as in the power of the cause from which all else emanates, not in the mode of distinct intelligibility or of true being as in the Nous. The realm of being is below the pure unity of the One.) And if the thinkers of the school of Chartres insist that these divine ideas or native forms, though simple and one in God, are nonetheless the true being of all things, then we have a metaphysical impasse. Either this is a metaphysical contradiction or incoherence, or true being is nothing but its being thought, has no being of its own but only that of the act that thinks it. This seems to me the conversion of the Neoplatonic realism into a latent idealism that is quite foreign to the original inspiration of the doctrine, and, I believe, to the explicit intentions of the Christian Neoplatonist thinkers themselves. Which side of the dilemma did they actually opt for? I have the impression that they were just not that clearly aware of the metaphysical implications of their thought and made no clear option, but remained oscillating ambiguously somewhere in the middle, unwilling to give up either end of the opposition.

But to be fair to them, the blame is not entirely theirs. They are trying to cope with the rich but enigmatic heritage of the Pseudo-Dionysius, who in his turn has tried to impose a new dialectic of the unmanifest-manifest divinity on the old Neoplatonic doctrine of the emanation of the world of ideas and the Nous from the One, but without making it that clear that some significantly new metaphysical laws have been introduced. Although something similar to the unmanifest-manifest dialectic can certainly be found in classical Neoplatonism, still the particular way in which Pseudo-Dionysius interprets it to hold onto the ontological simplicity of God—in terms of the divine “energies” which are both divine, God as manifested, and yet somehow multiple—seems to me to have a strong dose of oriental as well as Neoplatonic roots, unless one considers it an original creative Christian adaptation of Neoplatonism. I cannot go into this complicated but intriguing prob-lem here. The Dionysian doctrine has remarkable af-finities with the Hindu notion of the shakti, or divine power, of the “manifest” Brahman at work in the world. It was given central prominence later in the Eastern Orthodox theology of Gregory Palamas, but was rejected by Western Scholastic theologians. Like the doctrine of multiple divine ideas, it is filled with metaphysical tensions of its own.

Thirteenth-Century Scholasticism

We now come to a decisive new chapter in the history of our problem, one that finally provides a coherent metaphysical resolution to the almost 1,000 years of tension within Christian Neoplatonism. This solution emerges gradually during the twelfth cen-tury, due to the struggle over the reality of univer-sals, and finally comes to a head in thirteenth-cen-tury Scholasticism. Here the technical precision demanded of professors trained in Aristotelian logic and functioning in a professional academic commu-nity could no longer be satisfied with inspiring but metaphysically fuzzy pantheistic-sounding formulas that at the same time repudiated pantheism, or with the simple assertion of unexplicated paradoxes held together by metaphors such as “all forms fall back into the simplicity of the one divine form.” The crucial decision is finally made: the Platonic realism of ideas must once and for all be given up.

There seems to have been a fairly wide consensus on this point, though, as we shall see, not universal. It was not only the Aristotelian current of Albert and Thomas Aquinas that sponsored it: leading Augustinians such as Saint Bonaventure also agreed. In fact the latter provides us with an admirably succinct summary of the basic position:

God knows things through their eternal “rea-sons” (rationes aeternae) . . . . But these eter-nal intelligibilities are not the true essences and quiddities of things, since they are not other than the Creator, whereas creature and Creator necessarily have different essences. And therefore it is necessary that they be exemplary forms and hence similitudines re-presentativae of things themselves. Conse-quently these are intelligibilities whereby things that are are made known (rationes cognoscendi), because knowledge, precisely as knowledge, signifies assimilation and expression between knower and known. And therefore we must assert, as the holy doctors say and reason shows, that God knows things through their similitudes.27

The die is cast. The divine ideas are no longer the very forms, the true being, of creatures, but their intentional similitudes, whose only being is that of the one divine act of knowing. (It is quite true—as was objected in the discussion—that the divine ideas in Bonaventure seem to have a greater ontological density and dynamism than in Saint Thomas. But this remains the creative dynamism of the Word itself and is not the true being of creatures as for John Scottus. The very next question after the above quotation, whether there is any real, multiplicity in the divine ideas, makes this clear beyond the shadow of a doubt. Hence, the suggestion made that he qualifies his position in the next paragraph is entirely without textual foundation.) But the firmest and clearest grounding for this common position is provided by Thomas Aquinas, with his new metaphysics of the composition of essence and act of existence (esse) in creatures and the location of the real perfection of beings no longer on the side of form but on the act of existence of which form is limiting principle.28 Thus creatures have no true being until God as creative cause gives them their own intrinsic act of existence, which is not their intelligible essence but a distinct act by which form itself comes to be as a determinant structure of a real being. As creatures are precon-tained in the divine ideas, they simply do not yet have this act of their own intrinsic esse, hence are not yet properly beings at all, let alone the really real. Their “subjective” being is identified entirely with the being of the simple act of divine intelligence which “thinks them up” (adinvenire is the word Saint Thomas carefully picks out, which means to invent or think up, not discover, which would be invenire) as possible limited modes of participation in his own infinite act of esse subsistens.29 Thus their entire being is their being-thought-about by God, in a single simple act without any plurality of real being, though there is a clear plurality and distinction on the level of the objective intelligible content thought about by this one act. In a word, in the new technical ter-minology, the divine ideas are now only the “sig-nifying signs of things” (intentiones rerum), not things themselves; their being is esse intentionale not esse naturale or reale.30 This crucial distinction between esse intentionale and esse naturale, in terms of which alone the doctrine makes sense, is the one piece that has been conspicuously missing from the entire Platonic tradition, and for good reasons. To have admitted it would have blown up classical Platonism from within, or at least forced such a profound adaptation as to involve almost a change of essence. The term itself is an inheritance neither of the Platonic nor even the Aristotelian tradition, but from Arabic sources.

This single stroke of distinguishing the subjective being of ideas, which is nothing but the act of the mind that thinks them, from their objective content, their intentional meaning and reference which can be multiple and distinct, opened the way at last to a metaphysically coherent assimilation of the whole Eriugenian doctrine of the presence of the divine ideas in the Word in a single, simple act prior to any plurality. The latter was indeed a brilliant insight of Christian Neoplatonism, but one that could not make sense unless the doctrine that accompanied it in Eriugena—that of the ideas as true being in them-selves—was jettisoned. The divorce was painful, but inevitable. But this move also entailed the dropping of another cherished theme of classical Neopla-tonism, namely, that the passage from the divine ideas, or realm of true being, to their unfolded exem-plifications in the contingent world of matter is a passage to a lower mode of being, a degradation or diminution in being. Creation now becomes, on the contrary, a positive expansion from the merely mental being of the world of divine ideas to a new dimension of true being “outside” the divine Mind (extra causas), as an enrichment of the universe through a gracious free sharing of its own real perfection; for this real perfection is always in the line of actual esse, and this was not yet accomplished in the realm of the divine ideas by themselves.

The same move also forced, if not the total giving up, at least the drastic toning down and reinterpre-tation of another closely linked theme long cherished by Christian Neoplatonists in the pre-Scholastic period following the lead of Augustine himself.31 This is the notion that all creatures exist in a higher, more perfect state in the exemplary idea of each of them in the mind of God than in their own created being—especially so, but not exclusively, in the case of material beings. This theme still keeps recurring in the spiritual writings of Christian Neoplatonists, used as a potent motivation and intellectual model for spiritual growth.32 But its literal metaphysical force is now toned down.

Clearly Thomas Aquinas cannot hold this as a metaphysical doctrine—and not even Bonaventure, if he is to remain consistent with his text quoted above. For if, as I am present in the mind of God, I do not yet possess any slightest trace of my own intrinsic act of esse, in proportion to which alone is measured all my real participation in the perfection of God, then it cannot be literally asserted that I exist, have my true being, in a higher and more perfect state in God’s idea of me than in my own contingent created existence in myself. It is true that my intelligibility, the intelligible content of the divine idea of me, exists in a higher, more perfect way in God than in me; but this is still not my true being, my esse.

Thomas is quite aware that he is laying aside a long and venerable Augustinian tradition. But as is his wont in so doing, he never directly contradicts it, but reinterprets it to draw the most he can out of it without compromising his own metaphysical integ-rity.33 Thus in the present case he is quite willing to admit that there is a certain fulfillment for a material being to exist, as known, in a spiritual intelligence, a fortiori in God’s, since in being thus known the material mode of existence is transposed into a spiritual one, that of intentional existence, which is identical with the spiritual act of the mind knowing it. But this fulfillment can exist only if the material being already exists in its own material being and is also known in a spiritual mode. The real being of the material thing does not consist in its being known and the latter state cannot be substituted for the former with the full value retained. It does remain true, however, that the perfection of our real being is represented, held before us by the divine idea as an ideal goal, a final cause, drawing towards its actual realization through the drawing power of the Good reflected in it. It functions thus as a powerful motivation for spiritual growth toward the fulfillment of our true being to-be-realized; but it is not this true being already existing in the mind of God. For if the latter were literally the case, why bother with working out on an inferior level the same perfection already given on a higher level? This was the enigma haunting, as we saw, Eriugena’s emanation from the second to the third division of nature—a problem to which he gave no recognizably Christian solution.

All did not agree, however, with this deontologi-zing of the divine ideas. Henry of Ghent, teaching in Paris at the end of the thirteenth century, and drawing his inspiration both from Avicenna and Neoplatonism, complains that the more “current theological opinion” has gone too far in rejecting the doctrine of Eriugena and reducing the divine ideas to nothing but understood “modes of imitability of the divine essence (rationes imitabilitatis).” To this he opposes “the position excellently expressed by Avicenna in his Metaphysics, according to which the ideas signify the very essences of things.”34 Expoun-ding this position elsewhere he distinguished bet-ween two aspects of the ideas: (1) “the essences of things in the divine knowledge as objects known . . . which are really other (secundum rem aliae) than the divine nature”; and (2) “the rationes by which these are known, which are really identical with the divine nature.”35 To explain this he introduces his own technical terms of a distinction between an idea and its ideatum or object, and a distinction between the being of essence and the being of existence (esse essentiae and esse existentiale):

Since therefore the ideas in God exercise cau-sality in every way over the things of which they are the forms, by constituting them in both their esse essentiae and their esse exis-tentiae, and this according to the mode of the exemplary formal cause, therefore the relation of the divine idea to its ideata . . . is according to the first genus of relation, which is that between the producer and its product . . . so that it follows from the divine perfection that from the ideal ratio in God, the first essence of the creature flows forth in its esse essentiae, and secondly, through the mediation of the divine will, this same essence flows forth in its esse exislentiae.36

But the introduction into Christian thought of this Avicennian attempt to salvage Neoplatonism in a creationist universe, by means of a world of possible essences which, as someone put it, “stands up stiff with reality” (the reality proper to essence in itself, distinct both from the idea that thinks it up and its later mode of created actual existence), did not find hospitable acceptance among the thirteenth-century and especially later Christian theologians. The ghost of John Scottus Eriugena was no longer welcome at the banquet of Christian theology, although the overtones of the doctrine do linger on in Duns Scotus and down through Descartes, Spinoza, and the early rationalism of modern philosophy.

Fourteenth-Century Nominalism

We cannot conclude our story, however, without a brief word on the final denouement in medieval times. The thirteenth century gave birth to a careful balance between a firm maintaining of the presence and role of the divine ideas in God and a firm rejection of their identification with the true real being of creatures. The pendulum now swings all the way to the opposite extreme. The deontologizing of the divine ideas is pursued so relentlessly that the divine ideas themselves, even in their esse intentionale, finally disappear entirely. This is the work of William of Ockham and his nominalist followers. His sledgehammer metaphysics, pairing the principle of contradiction with the divine omnipotence, will allow no medium between full reality—evidenced by full real distinction and separability—and nothing at all. One of the first casualties is the esse intentionale of the great thirteenth-century metaphysical systems. Either the so-called divine ideas are real being, and thus real multiplicity, in God—which a Christian thinker cannot accept—or they are nothing at all. The divine ideas, venerable tradition though they be, must be resolutely jettisoned in the name of Christian thought purified of all pagan Platonism. Nothing in the divine nature is immutable or eternal except the being of God himself. But God is not an idea:

The divine essence is not an idea, because I ask: the ideas are in the divine mind either subjectively or objectively. Not subjectively, because then there would be subjective plurality in the divine essence, which is manifestly false. Therefore they are there only objectively: but the divine essence does not exist only objectively (i.e., as the object of idea). Therefore it is not an idea.37

As Gabriel Biel, a later Ockhamist disciple, puts it succinctly:

These two, namely, immutability or eternity, and multiplicity or plurality, do not seem com-patible (for the divine essence, which is immu-table and eternal, does not allow that plurality which is posited among the ideas—for each creatable thing has its own proper and distinct idea—and although this plurality is proper to the creature, immutability and eternity are not, but are proper to God alone).38

The so-called divine ideas must therefore be ba-nished from God and identified simply with creatures themselves as the direct objects, without interme-diary of any kind, of the divine act of knowing. The danger of this position, of course, as became all too clear with the unfolding of nominalism, was that, in the name of saving the divine simplicity, all intel-ligible structures of creatures as causally prior to creation also seem to have vanished from the divine mind, and we are threatened with an unfathomable abyss in God of pure unillumined will power which seems at the root of intelligence itself, leading to the substitution of divine will rather than intelligence as the ground of morality. As Biel does not hesitate to put it: “It is not because something is right or just that God wills it, but because God wills it therefore it is right and just.”39 With the banishment of the divine ideas, we have now come full circle in the spectrum of positions within Christian thought. The divine simplicity has been preserved, but at the expense of that other pillar of traditional Christian metaphysics, which Saint Thomas and other thirteenth-century Christian thinkers worked so hard to bring into equilibrium with the divine simplicity, the theory of divine exemplary ideas. The total negation of the Neoplatonic world of ideas is as unacceptable in Christian philosophical thought as its ultrarealism. A Christian metaphysics of God can survive only at a point of balance in the middle. Professor Anton Pegis has made the suggestion, in a brilliant article on “The Dilemma of Being and Uni-ty,”40 that in thus moving to such an extreme anti-Platonic position, Ockham and the nominalists are still the unconscious prisoners of Platonic thought, accepting uncritically one of its basic presuppo-sitions; namely, that the world of intelligibility is necessarily and unavoidably a world of real multiplicity. The Neoplatonists drew the conclusion that, since being and intelligibility were necessarily correlative partners, then the supreme source of reality, the One, must be beyond both being and intelligibility. The nominalists drew the conclusion that, since the supreme principle must be being, Ultimate Being itself must be raised above intelligibility. But both conclusions proceed from the same premise. The only solution is to do away with the premise itself—that an intelligible order is necessarily linked to real multiplicity. It was this decisive move, rendering Christian Neoplatonism finally viable, that we owe to Saint Thomas and other Aristotelian-influenced thinkers of the thirteenth century.

Conclusion

To sum up briefly, the key point I have tried to make, as a metaphysician reflecting on the history of a problem, is that, although large areas of Neoplaton-ism can be assimilated for the profound enrichment of Christian thought, there is one doctrine that stubbornly resists coherent assimilation: this is the doctrine of the realism of ideas, that the true being of things consists in the pure ideas of them as found in the mind of God (or elsewhere). This is inconsistent first and foremost with the Christian notion of the existential identity of all the divine ideas, however distinct in their intelligibility or esse intentionale, with the one simple act of the divine mind thinking them, so that there is no real plurality in God outside that of the three divine Persons. It is also inconsistent, though this point remained more latent in actual medieval discussion, with the value given to created existence as the gift of God’s love and the decisive value given to human salvation freely worked out in contingent history through the Incarnation of the Son of God and the free moral response of historical man. The chapter we have just studied illustrates once again that the encounter between Neoplatonism and Christian thought was a deeply challenging one, where genuine assimilation and viable synthesis could be brought about only by profound creative adaptation, in some cases even the final rejection, of some aspects of Neoplatonism.

Notes

1 Cf. Plato’s famous description of the ideas as “the really real” (to ontos on) in Phaedo 65-66 and other classic discussions of the ideas.

2 Cf. Parmenides 1321b-c (trans. Cornford):

“But Parmenides, said Socrates, may it not be that each of these forms is a thought, which cannot properly exist anywhere but in a mind? In that way each of them can be one and the statements that have just been made would no longer be true of it.

Then, is each form one of these thoughts and yet a thoughl of nothing?

No, that is impossible.

So it is a thought of something?

Yes.

Of something that is, or of something that is not?

Of something that is.”

3 Cf. Enneads VI, 7, 15-16 (trans. MacKenna-Page), and occasionally through V, 1-2. In these passages the Ideas are spoken of as the product of the Intellectual-Principle.

4 Enneads V, 9, 7-8. Cf. also V, 3, VI. 6, 7-8, and off and on throughout V, 1-2. The essence of the position is that Nous and its objects constitute a single interdependent relational unity, neither properly prior to the other, but constituted together as a unitary life simultaneously by the overflow of the Good. But see VI, 6, 8 for a priority of being, over Nous: “First, then, we take Being as first in order: then the Intellectual Principle . . . . Intellectual Principle as the Act of Real Being, is a second.” The Greek texts here are entirely clear, the terms used being pro, proteron, etc.

5 This doctrine is clear, explicit, and constant throughout the Enneads. Cf. V, 1, 4; V, 6; V, 3; 10-15; V, 6; V, 9, 6; VI, 6, 9; VI, 7, 13 and 17. The intellec-tual realm is always a one-many, both because Being as object is distinct from the act that knows it and because each Being-Idea is distinct from every other, though not divided from it.

6 Anton Pegis has admirably summed up the dilemma posed to Christian thought by the Platonic world of ideas: “St. Augustine . . . thought to baptize the Pla-tonic Forms and to make them ideas in the mind of God. But this was easier to assert than to accomplish philosophically. For the perplexing mystery of the Platonic Forms is that in a Christian world they can be neither God nor creatures. They cannot be creatures because they are immutable and eternal; and they cannot be God because they are a real plurality of distinct and distinctly determined essences. Yet they rose before the minds of Christian thinkers again and again, and they hovered somewhere on the horizon between God and creatures, strange aliens both from heaven and from earth, and yet aliens whose message proved so enduringly dear to Christian thinkers that, rather than forget it, they exhausted their energies in pursuing it.” “The Dilemma of Being and Unity,” in R. Brennan, Essays in Thomism (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1942), pp. 158-159. The whole article, in fact, is a brilliant example of a truly philosophical study in depth of the history of philosophy.

7 Cf. for example his famous brief treatise on the ideas, De Diversis Quaestionibus LXXXIII, Qu. 46 (Migne, Pat. Lat. XL, 29-31), and other standard references.

8 Cf. F. J. Thonnard, “Ontologie augustinienne,” L’Année théologique augustinienne 14 (1954), 39-52, esp. pp. 42-43. Clear texts are in Augustine De Trin. V, 2, 3: “Ab eo quod est esse dicta est essentia,” and De Immortalitate Animae XII, 19: “Omnis enim essentia non ob aliud essentia est, nisi quia est.”

9 De Trinitiate V, 2, 3.

10 Sermo VII, n. 7.

11 De Moribus Manichaeorum VII, 7.

12 Contra Manichaeos, c. 19 (PL, XLII, 557). On the above texts see V. Bourke, St. Augutstine’s View of Reality (University of Villanova Press, 1965), and J. Anderson, St. Augustine and Being (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1966).

13 It has been called to my attention, however, by the Augustinian scholar, Robert J. O’Connell, that Augustine, in Confessions X, C. 9-12, when speaking about memory, distinguished between the sensible images of past contingent events, such as going to the Tiber river, and the intellectual intuition of num-bers and their relations, which intuition puts us in contact with the very things themselves (res ipsae), with the very reality of numbers, which truly are (valde sunt), hence buried deep in our intellectual memory, which is always in contact with the immu-table and eternal truths of the intelligible world through divine illumination. Now since, as rationes aeternae, numbers are certainly on a par with all the other rationes aeternae, it would seem necessary to conclude by analogy that all the rationes aeternae are also res ipsae, et valde sunt (c. 12). Yet Augustine never quite seems to go this far or work out the implications.

14 On John Scottus Eriugena’s doctrine, see M. Cappuyns, Jean Scot Erigène (Paris: Descléc, 1933): H. Bell, Johannes Scotus Erigena (New York: Russell & Russell, 1964); J. Trouillard. “Erigene et la théophanie créatrice.” in J. O’Meara and L. Bieler, eds., The Mind of Eriugena (Dublin: Irish Univ. Press, 1973), 98-113; T. Gregory, Giovanni Scoto Eriugena (Florence: Felice Le Monnier, 1963), ch. I: “Dall’ Uno al Molteplice”; and the standard histories of Gilson, etc.

15 Cf. De Divisione Naturae II, c. 36 (I. ed. Sheldon-Williams, Johannis Scotti Eriugenae Periphyseon, Dublin Inst. for Advanced Studies, 1972. pp. 205ff.). See also other main discussions of the primordial causes, De Div. Nat. III, c. 1-17 (M. Uhlfelder and J. Potter, John the Scot: Periphyseon—On the Division of Nature, Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill, 1976).

16 De Div. Nat. II. c. 4-9. Thus material things exist more perfectly even in the mind of man, as spiritual, than in themselves.

17 De Div. Nat. III, c. I (trans. Uhlfelder and Potter, p. 129): “The first causes themselves are, in them-selves, one, simple, defined by no known order, and unseparated from one another. Their separation is what happens to them in their effects. In the monad, while all number subsist in their reason alone, no number is distinguished from another, for all are one and a simple one, and not a one compounded from many. . . . Similarly the primordial causes while they are understood as stationed in the Beginning of all things, viz., the only-begotten Word of God, are a simple and undivided one; but when they proceed into their effects, which are multiplied to infinity, they receive their numerous and ordered plurality. . . . all order in the highest Cause of all and in the first participation in it is one and simple distinguished by no differentiae; for there all orders are indistinguishable, since they are an inseparable one, from which the multiple order of all things descends.”

18 Thus in Enneads VI, 6, 9 in the order of Being in the Nous number is declared to be already unfolded, not as it is in the Monad or One. In V, 3, 15, all the ideas are unfolded as distinct in the Nous, which thus becomes a one-many, whereas the One should not be said to contain all things as in an indistinct total. See the other texts in note 5. Thus what Eriugena describes as the mode of the primordial causes in the Word is explicitly denied by Plotinus of the divine Nous and could be applied only to the One, in which the ideas could in no way be said to be present

19 De Div. Nat. II. c. 20 (ed. Sheldon-Williams, p. 77).

20 Ibid., II, 8 (ed. Sheldon-Williams, p. 29). For this identity of the being of things with the thought of them, see Bett, op. cit., in n. 14, pp. 51, 145; Gregory, op. cit., in n. 14, p. 12: “Gli essere nella mente di Dio si risolvono nell’atto con cui elgi li conosce.”

21 Cf. E. Gilson, History of Christian Philosophy in the Middle Ages (New York: Random House, 1954), ch. III: “Platonism in the Twelfth Century”; H. Häring, Life and Works of Clarembald of Arras (Toronto: Pontifical Insitute of Medieval Studies, 1965).

22 Clarembald of Arras, Tractatus super Librum Boetti De Trinitiate (ed. Häring, op. cit., in n. 21), II, 41, p. 123.

23 Ibid., II, 29-30, p. 118: “Forma sine material est ens a se, actus sine possibilitatae, necessitas, aeter-nitas . . . et ipsa Deus est.”

24 Thierry of Chartres’ commentary on Boethius’ De Trinitate, called Librum Hunc (ed., W. Janssen, Der Kommentar des Clarembaldus von Arras zu Boethius De Trinitate, Breslau, 1926, p. 18): “Omnium formae in mente divina consideratae una quodammodo forma sunt, in formae divinae simplicitatem inexpli-cabili quodam modo relapsae.”

25 See note 21.

26 Tract. Super Lib. Boet. De Trin. I, 34 (Häring, p. 99): “Omnis multitudo in simplicilate unitatis complicate latitat, et cum in serie numerandi post unam alterum et post alterumtercium numerator, et deinceps tunc demum certa pluralitatis ab unitate profluentis forma cognoscitur, sicque sine alteritate nulla potest esse pluralitas.”

27 De Scientia Christi, q. 2, c, Responsio (Obras de S. Buena ventura, Bibl. De Autores Chrisitianos, Madrid, 1957), p. 138. Cf. also q.3.

28 Cf. the standard treatments of the ‘‘Thomistic existentialism,” introduced by St. Thomas: E. Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas (New York: Random House, 1956), the famous chapter I on “Existence and Reality”; J. de Finance, Etre et agir (Rome: Gregorian University Press, 1960, 2nd ed.); and my own summaries: “What is Really Real?” in ed. J. Williams, Progress in Philosophy (Milwaukee: Bruce, 1955), pp. 61-90, and “What is Most and Least Relevant in the Metaphysics of St. Thomas Today?” Internal. Phil. Quart. 14 (1974), 411-434.

29 For Thomas’ treatments on the divine ideas, see Sum. c. Gentes IV, c. 13, no. 10; Sum. Theol. 1, q. 15 entire; I, q. 44, a. 3; 1, q. 18, a. 4: “Whether All Things are Life in God”; De Veritate, q. 3, q. 4, a. 6 and 8. The description of the divine ideas as “invented” by God is in De Ver., q., 3, a. 2 ad 6 m; as rationes quasi excogitates is in De Potentia, q. 1, a. 5, ad 11 m.

30 For Thomas’ fundamental criticism of the Platonic realism of ideas, see In I Metaph., lectio 10; In I De Anima, lect. 4, and the general discussion with texts in R. Henle, St. Thomas and Platonism (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1956), part II, ch. 4: “Basic Principles of the Via Platonica.”

31 De Trinitate VI, c. 8.

32 Cf., for example, the great Flemish mystic, Jan Ruusbroec. “According to the Flemish mystic, man’s true essence (wesen) is his superessence (over-wesen). Before its creation the soul is present to God as a pure image; this divine image remains its super-essence after its actual creation.” Louis Dupré, Tran-scendent Selfhood (New York; Seabury, 1976), p. 103-104.

33 See the texts in note 29, in particular Sum. Theol. I, q. 18, a. 4; De Ver., q. 4, a. 8; Sum. c. Gentes IV, c. 13. n. 10 (Pegis trans.), and the special article just on this point, De. Ver., q. 4, q. 6: “Whether Things are More Truly in the Word than in Themselves.” In I Sent. d. 36, q. I, q. 3 ad 2 m (M837): four modes of esse creaturae.

St. Thomas’ point is that if one looks at the mode of being of the thing in itself and in an idea (God’s or man’s), the mode of being in an idea, especially the divine idea, is a spiritual mode, identical with the being of the mind thinking it, hence from this point of view higher than the material being of a thing in itself; but if one considers the proper mode of a thing’s own being as this thing, this is found only in the thing’s own material being and not in its idea. Properly speaking, a thing’s own being is not found in its idea. Thus Thomas is able to preserve intact the traditional formulas about the existence of things in the Word as more perfect, but the meaning he gives to them is notably different from their original intention, where his distinctions were not yet made.

34 Henry of Ghent, Quodlibeta IX, 2, cited in the fine study by Jean Paulus, Henri de Gand (Paris: Vrin, 1938), p. 91. n. 1.

35 Summa, 68, 5, 7-14, cited in Paulus, loc. cit.

36 Loc. cit.. Cf. the illuminating remarks on Henry and his place in the history of our problem by Anton Pegis, art. cit., in note 6 above. esp. pp. 172-176.

37 In I Sent., d. 35, q. 5; cited in Pegis. art. cit., p. 170.

38 Gabriel Biel, In I Sent., d. 35, q. 5C (Tübingen, 1501); cited in Pegis, p. 159.

39 In I Sent., d. 17, q. I, a. 3K; Pegis, p. 171.

40 Art. cit. in note 6, pp. 168-172.