AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From Charles Hartshorne’s Concept of God: Philoso-phical and Theological Responses, edited by Santiago Sia, Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1990, 103-123. See also Hartshorne's reply.

Anthony Flood

May 22, 2010

Charles Hartshorne’s Philosophy of God: A Thomistic Critique

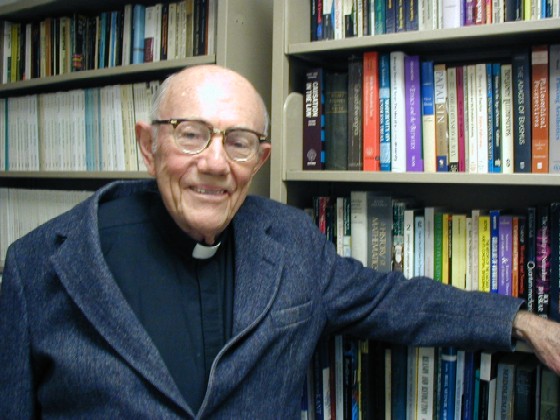

W. Norris Clarke, S.J.

Let me begin by saying quite sincerely that I find Hartshorne’s philosophical theology a truly “noble” one. It articulates a rich religious sensitivity and presents us with a God that is a totally admirable person, worthy of deep religious reverence and love. It is not surprising to me that some of the authors who have written on it declare that this is the only brand of theism they could accept.

He also reveals himself as a genuine metaphysi-cian of a high order. His remarks on what metaphy-sical “proofs,” or “arguments” (as he now prefers to call them) can be expected to deliver today, his notion of cumulative arguments for the existence of God, his critique of negative theology and defense of meaningful positive language about God, and many other observations, all show a highly developed philosophical as well as humane wisdom. Some of his arguments, too, for the existence of God, especially from cosmic order, I find quite good, or at the least very helpful in refining my own.

In what follows I shall not focus on his arguments for the existence of God. That would be too long and technical a job to be carried out adequately here. I wish to concentrate on the conception of God which results from his analyses, to investigate whether or not it satisfies adequately the exigencies of a rea-sonable metaphysical explanation of our world and experience—which is what he too admits is the goal of a philosophy of God. My point of view will be basically inspired by the metaphysics and natural theology of St. Thomas, but with a certain indepen-dence of traditional expositions of Thomism, as will appear, an independence in fact inspired by my own sympathetic study of process philosophy. I believe St. Thomas’s metaphysics can go much further in solving the key problems of natural theology—truly difficult for any philosophical system—than Harts-horne is willing to admit, though too often Thomas does not proceed far enough in articulating the resources of his own system. In fact I do find that Hartshorne systematically misunderstands—to my mind—some of the key metaphysical issues which St. Thomas is trying to come to grips with in his conclusions and so inevitably misinterprets St. Thomas himself in these cases. I shall focus on a few key points.

II. Is God the Cause of the Being of Creatures?

The religious intuition which nourishes Harts-horne’s metaphysical explications is very rich, and so is what I might call without pejorative connotations his literary and rhetorical expression of what he understands to be the religious implications of his metaphysical analyses. Thus in particular he speaks movingly of God as the ever-present collaborating—though not totally determining—cause of all crea-tures and their activities. But my difficulty arises when I press the metaphysics hard to see if it ade-quately supports the descriptive statements. Here I must say that I find less than meets the eye: Harts-horne’s God does not seem to be the genuine cause or source of the very being and power—creativity—of creatures. He does indeed provide their initial subjective aim, set the general limit laws of the cosmos for their activity, and influence them by allowing them to prehend his intentions, etc. But all this is influencing them only. It presupposes they are somehow there for Him to influence, at least with some initial inchoate being handed on from their predecessors. But He is not the radical ultimate source of their very being itself, or of their power to act with a certain creative spontaneity. Hartshorne is so afraid of making God the “tyrant” determiner of all activity—which I agree with him is certainly an intolerable view—that he is reluctant even to let God be the source of the power of His creatures to be creative.

He would answer by rejecting creation ex nihilo as implying an absolute beginning of the cosmos, which he finds opaque in intelligibility. Thus there are always previous entities which as they perish are partial causes, with God, of the new actual entity. But even if one concedes the intelligible possibility of an infinite series of entities or events in a universe without beginning or end, as he does—which, by the way, I am now coming to think more and more, contrary to St. Thomas, does not make sense—one is still left with the situation that nowhere can one find any sufficient reason for the actual existence and real power of any of God’s creatures, all of which are contingent creatures. An infinite eternal series of all contingent beings never can add up to an adequate sufficient reason for the being of any of them.

Let me put it this way. God is not the ultimate radical source for the very being and power of contingent beings. He influences them profoundly, but always presupposes their initial being as handed on by their predecessors. So the predecessors are in fact more the cause of the actual power-filled being of their successors than God is. But the trouble is that none of these prior contingent beings is the adequate sufficient reason for its own being and power, since that depends on the gift of a prior, and the latter in turn depends on a prior, and so on to infinity. Thus we are endlessly in search of the sufficient reason for the actual existence of any member of the series, and can never in principle find it. The burden is always passed back to a prior.

It does no good to say that each one is ade-quately taken care of by its predecessor; that would be true only on the presumption that the latter’s own being was already adequately taken care of. But it turns out that it is not taken care of by itself and requires some previous conditions to be fulfilled. It can exist only if these are already adequately fulfilled. It now turns out that its predecessor’s conditions are not fulfilled by itself either, so the buck is passed back further. We now have the situation that each member of the series exists only conditionally, i.e. if another exists, and the latter too only if another, and so on without end. In other words, A exists only if B, B only if C, C only if D, and so on indefinitely. But from a series of all conditionals one can never get an unconditional affirmation. Yet the present being which we are trying to explain does in fact exist unconditionally. Hence somewhere along the line of its cause there must be one whose existence is affirmed absolutely, without further conditions, in a word, one that is its own sufficient reason for existing.

Our search for a sufficient explanation goes upstream in time, and once we have gone far enough back we tend to think we don’t have to worry further, for every member will be taken care of by one further back. But the actual flow of being comes the other way, down from the past to the present. So unless there were a completely sufficient reason, i.e. a self-sufficient being, already in place in existence there would be no sufficient reason why the flow of being through the entire series ever got started in the first place or is actually going on at all (if eternal). Thus either there is a self-sufficient cause at the start of the series, which would then have a beginning, or else outside the whole series, supporting the entire being of the series all the time. The universe of Hartshorne has many partial causes of its ongoing being, one of which, God, has the sufficient reason for its own existence, but He does not provide this service fully for the contingent members. And since none of them can provide this for themselves, nowhere is there any sufficient grounding for the entire cosmic system, no matter how far back into an infinite past one goes. Thus it is not clear in his system why in fact there actually are any other beings outside of God himself.

Actually, why could not Hartshorne simply enrich his system and say that God is the ultimate source of the very being and creative power of all His creatures, and then continue with all the other things he wants to say, that God does not determine them fully, works with them by persuading them, etc.? I can see only two significant reasons for his not doing so, neither of them cogent. One would be if he held the position many claim is that of Whitehead, namely, that the very being, the total being, of any creature is identical with its act (its “concrescence”) without remainder, so that there is no shadow of distinction whatever between the subject of the activity and the activity itself. In that case, of course, God could not be the cause of the being and power of the creature, because then He would be the cause of the very act itself, the very determiner and doer of the act; and no being, even God, can actually do, or better posit, the act of another being. Therefore the creature must be radically self-creative of its own initial inchoate being and power by which it responds to the subjective aim God imparts to it.

Some of the younger Whiteheadians, like Jorge Nobo, have argued—cogently, I think, against Lewis Ford—that not only does this not make sense in itself metaphysically (I agree), but is not the proper interpretation of Whitehead. Whitehead in many texts asserts, in addition to the creativity at work in the new actual entity’s own concrescence, a transi-tional creative energy passing over from the peri-shing prior entity to the new, establishing it, with God, in its initial inchoate being, which then by its own creativity decides what to do with what it has been given—including the power it has been given. From what I can see in Hartshorne, it does not seem to me that he holds, or needs to hold, this extreme identification of the whole being and power of an actual entity with its act (the expression of its creativity). I do not see, then, why Hartshorne cannot hold that God is the ultimate source of both the being and power of the creature. And if he can, he should.1

II. Is God Omnipotent?

The other reason—and I think the really central one—why Hartshorne does not go on to make God the ultimate source of the very being and power (not just the subjective aim) of his creatures is his fear that such a radical giving of being to all his creatures would imply the omnipotence of God. And he is absolutely adamant about rejecting such an attribute as inappropriate to God. Here is the real bête noire. The very term is like a red rag to a bull for Harts-horne—and for good reasons if the classical notion were what he understands it to be. “Omnipotence,” for him, seems to mean that God is not only the source of all power but also holds onto it all, determining all actions himself, so that He is the sole powerful one, so to speak. This would of course eliminate all creativity, spontaneity, and freedom from His creatures, which would be more like robots or puppets than authentic agents. Such a notion of divine omnipotence should indeed be rejected.2

But this is not at all what the classical notion of omnipotence means, in St. Thomas, for example. This is one of the main criticisms of Thomists against both Hartshorne and Whitehead, who held much the same and declared it explicitly to be one of his main reasons against creation from nothing. In St. Thomas, for example, “omnipotence” means (1) that God is the infinite source and fullness of all power, and (2) that He can produce or bring into being any entity that is intrinsically possible, not contradictory. It does not mean that He can do by himself any act or action of a being, such as, for example, drinking beer, sneezing, having sex. Above all it does not mean that He holds onto all the power, determining all actions unilaterally. Precisely the opposite is true. He is the one who shares his power most freely and generously. Every creature, as an image and partici-pation in the perfection of God, participates according to its nature in the divine fullness of power, and has natural built-in capacity and positive tendency to flow over into self-expressive action. St. Thomas specifically criticizes the Arabic Occasionist philosophers, who, on the pretext of glorifying God more, reserved all exercise of power to God alone. To belittle the power of creatures is to belittle the perfection of God himself, he says, for the greater and more perfect an agent is, the more richly it can share its power.3 God is the ultimate source of all power, but not the sole holder and exerciser of it. Neither Whitehead nor Hartshorne seems ever to have been tuned in to the full richness of the doctrine of participation in Thomistic metaphysics, especially in its application to God and the relation of creatures to Him.

Thus God is the ultimate self-sufficient source of all the being and power (or nature, as an abiding center of activity) of His creatures. He also actively works with their natures as they produce their actions, supporting both their natures and their acts in their being all the way, as the universal Transcendent Cause. But He does not determine their acts on his own. The creaturely agent itself determines, according to its nature (necessary or free), how it will let the freely offered power of God flow through it, in this particular way or that. Thus in the case of free human actions, Thomas says that God predetermines, premoves, or pre-orients the will as nature towards the good as such—which means in the concrete the Infinite Good, desired implicitly in the choice of any finite good—but man decides whether to will in act this or that good in particular. The once and for all orientation, or magnetizing, of the will towards the Infinite Good puts the will in a permanent state of actuation which virtually (or “eminently”) contains within it the power to determine itself to this or that finite good.4

There is, I concede to Hartshorne, a more “ex-treme,” rigorous brand of Thomism, the school of Bañez, the great Dominican commentator on St. Thomas, still followed by many—not all—Dominican Thomists, which maintains a stronger predetermining power of God over every action, though at the same time they insist God causes our free actions to be free. I am not sure I can make good sense out of this language—it seems to me more like a verbal decree than an explanation. I can well understand Harts-horne’s unhappiness with this kind of Thomism, which he may possibly have taken to be essential to all Thomistic natural theology. But he should be aware that the large majority of Thomists—including all Jesuit Thomists, for example—do not hold this rigorist interpretation of St. Thomas.5 Nor do I believe it is an accurate rendering of Thomas’s own teaching. Witness the text of Thomas I referred to above about God predetermining the will as a nature to the good as such, but leaving it to the will itself to choose this or that good in particular.6

As I would put it myself, God offers constantly and unfailingly His superabundant power to his creatures, not yet determined in detail, and then each one determines or “steers,” so to speak, this power along this or that particular line according to the nature of each, necessarily or freely as the case may be. This may be much closer to what Hartshorne is holding out for than he may suspect. But my main objection remains: he shows no appreciation of the authentic classical doctrine of St. Thomas—and of others—that of the divine omnipotence as source of all power but freely shared, participated, with all his creatures. The doctrine of participation—so central to Thomas’s metaphysics as understood today—seems to be sig-nificantly missing, or hardly mentioned, throughout the whole of Hartshorne’s doctrine of God, as is even more true of Whitehead’s. Hartshorne does indeed divide up the total causality in the creature’s activity between God and the creature’s own spontaneous initiative; but the creature’s own contribution does not seem to be a participation in God’s own power but rather entirely self-caused, originating in a sense from nowhere.

III. Panentheism

This term sums up one of the central theses of Hartshorne, namely, that the basic metaphysical relationship between God and creatures is one of inclusion. God and creatures cannot be “outside” each other; they must form a single all-inclusive reality, which can best be described—analogously, of course, because it is a unique case—on the model of the relation of soul to body in us. The soul guides and controls all its cells so that they belong to it and fall under its power; thus they do not have full autonomy of their own. Yet they do possess a certain indepen-dent spontaneity on their own, as do the actual entities in any nexus or society. Thus like any organism, God and His creatures form a single inclusive whole—in this case an all-inclusive whole. Sometimes Hartshorne prefers to alternate between the model of a society—in the ordinary social mean-ing of the term—and an organism. Still he definitely prefers and often develops uniquely the model of organism.

I would like to lodge a strong metaphysical demur to this position. The intention behind it is a good one, to insure the intimate presence of God to his crea-tures. But it seems to me just another perpetuation of an old metaphysical misconception founded on a misleading image. Hartshorne finds himself in distinguished company indeed, since the great Hegel falls into the same trap. It came up in medieval times, in the guise of the obvious objection that creatures cannot be distinct in being from God, if God is infinite, since God + creatures would make more being than God by himself. The classic answer seems to me decisive, yet strangely never seems to have been noticed by modern philosophers. It is built entirely on the theory of participation. As the medievals put it, God + creatures = plura entia, sed non plus entis. That is to say, there are more beings, more sharers in being, but not more qualitative intensity of the perfection of being itself; or, if you wish, there are more sharers in perfection but no higher level of perfection. The infinity of God is not at all to be conceived in implicitly spatial, quantitative terms, as though if there were creatures “outside” of Him His being would end here and beyond that would be further being; hence His being could not be infinite. “Outside” God in classical terminology means simply, in non-metaphorical language, “not identical with God; they are not God.”

Thus to have more sharers in God’s perfection by no means implies there is now a higher level of quali-tative perfection. A simple example will illustrate the point. Suppose one has a mathematics teacher with a vast knowledge of mathematics, and he then shares it partially with a number of students. There are indeed now more sharers, partakers, in his mathematical wisdom, but no more (higher or fuller) mathematical wisdom around—save in the accidental sense that a human teacher may learn more in the very process of teaching. God’s infinity, then, is qua-litative exhaustiveness of perfection, not a quanti-tative or spatial inclusiveness of all other lesser spaces. It is an intensive, not an extensive concept. Thus there is no need at all that God + the world be a single all-inclusive reality, as Hartshorne insists, under pain of God’s being limited by creatures.7

In addition to the fact that there is no need for this panentheistic conception of God and creatures in order to protect the infinity of God, there are serious positive drawbacks to it. The main one is this. In any genuine organism that is somehow intrinsically one—not just an aggregate of externally related members like a society—the soul (even the human soul for St. Thomas) in some significant way depends on its body (at least for its ability to operate naturally, if not for its radical existence), and of course the body in its turn depends even more on its soul. Now Hartshorne is quite willing to say that God depends on the world, but only in order to have an object to work with, to receive His gracious gifts, and also to enrich His own satisfaction. He does not depend on it for help in the actual carrying out of His own internal operations, but only as an external object of His gifts and a source in return of further satisfaction. But such is precisely the relation of a workman to his materials, e.g. a carpenter to his supply of wood and to his finished product as a source of satisfaction. And this is not an organic relation at all. The carpenter does not need his wood to help him carry on internally the working of his own muscles and brain in carving the wood. The carpenter and his desk in no way constitute a single organic whole, though their non-organic relation is intimate and profound.

If we turn back to God now, and insist that He is in an organic, not a craftsman relation (as the Platonic Demiurge is wisely described), then His dependence on His world must be—if the organism analogy is to retain any force—much more profound than I believe Hartshorne would be willing to accept. God would have to depend on His creatures for help in the very internal carrying out of His own causality; He could not even do “his own thing,” so to speak, without the internal collaboration of His creatures in His own actions. This is no longer a Transcendent God in any sense of the word, merely the most powerful part of the one total organism, who would presumably need the help of His creatures even to think up the modes of possibility, just as our soul—the highest instance of organism we know, with a transcendence in being, but not in initial operation, over its body—needs its body to provide the initial phantasms for its abstractive power to work with. If God needed the world in order to carry on his own internal operations, then He and the world would constitute a mutual circle of dependence that would require some higher cause to put them together initially as an interde-pendent composite. For if A depends on B for its ability to actually operate, and B in turn depends on A for the same ability, then each presupposes the other already existing and operating in order for it to operate, and vice versa. In this case neither could get going unless some unifying higher cause posited them both in being as a simultaneous unitary being.

There is another, perhaps more serious, difficulty from our side of the picture. It is hard to see how there is place for genuine freedom, lucid and deliberate, for the genuine self-possession proper to the dignity of the person, if it is part of an organism. To be such a part means—if we are to give any strength to the term “organism”—that the organism can claim all its parts and hence their actions as mine. That means that God would have to lay claim to all our actions, including our evil ones, as His. This would make Him responsible for evil, even our moral evil, which is exactly the opposite of what Hartshorne maintains with such vigor elsewhere. The respon-sible self-possession and independence of the free person seems to me intractably resistant to being considered as a “part” in any significant not merely societal sense of a larger whole which somehow owns it as its own, and so can say “It is mine.”

Thus in conclusion it seems to me that (1) the conception of the God-world relation as panentheistic is not needed, because based on a implicit spatial misconception of the qualitative infinity of God, and (2) the conception of a soul-body organismic relation, unless one attenuates it beyond significant meaning, inevitably implies too strong a dependence between the two—more than Hartshorne himself would want. If he let go of the implicitly spatial conception of infinity and shifted to a participation model, he would not need his organic model at all. And the participation model would not necessarily imply that he give up what is most dear to him, the profound receptivity of God towards His world.

It seems to me that the terms “in God” and “out-side of God” are both too tied to metaphor, not pro-perly literal even in an analogous way. The spatial connotations remain too strong. More proper and precise metaphysical terms wold hav to be simply “is identical with, or a part of, the being of God,” as op-posed to “is not identical with, or a p art of, the being of God.” If one wishes, however, touse the expres-sion “in God”—and it does have a venerable history, even occasionally in religious language, e.g. St. Paul’s “in Him we live and move and have our be-ing”—one can say meaningfully that all creatures are within the field of God’s all-enveloping loving pre-sence and power, as He constantly and attentively supports their existence and works with their natures through His power. Thus in terms of the identical reason—His omnipresence through creative and supportive power—we can say, as we wish, that God is “in His creatures” or that they are “in Him” (within the field of His power). It would seem to me that the really central concerns of Hartshorne could still be adequately taken care of within this mode of speaking.

IV. God as Dipolar: Finite and Infinite

Here we come to the heart of Hartshorne’s most distinctive and original contribution to philosophical theology: his conception of God not as a simply infinite, “monopolar” Pure Act, but as dipolar in His very being, that is, infinite in His eternal potentiality, in His “existence,” as he puts it, but finite in his concrete actuality as he receives through time the ever growing accumulation of the experiences of all his creatures, thus constantly enriching his own trea-sury of value. This is the God who is totally receptive to all that happens, the universal Effect (because affected by everything) as well as the universal Cause, the God who grows with us in his actuality through time, but is both absolutely unsurpassed by any other being and unsurpassable in richness of goodness, power, perfection, love, knowledge, etc. by any other, that is, unsurpassable by any but himself.

There is much that is truly admirable in this con-ception. And I think there is no doubt that Harts-horne’s central description of God as the Unsurpas-sable by any but himself is indeed an original contri-bution to philosophical theology—and a brilliant one in its own way. The finite side of it (and the infinite as well) has its problems, as we shall see. But to my mind the central positive contribution that must somehow be integrated into any metaphysical con-ception of God that is compatible with our religious experience and language, at least with the image of the Judaeo-Christian God, is this: that God is infinitely sensitive to all that goes on among us in time, and infinitely receptive of our responses to His love. All His creatures, and especially His free personal ones, make a great difference indeed to God’s conscious-ness, so that He is truly related to them as they are to Him (although in his own distinctive way).

To interpret the immutability and Pure Act of God as though nothing of what happened among His crea-tures made any difference at all to Him, as though He were indifferent to our responses, would result in a God of philosophy too alien to our religious sensibi-lities to be acceptable as an articulation of what is the case, or at least of what we firmly believe to be the case. Our life and our thought cannot be that far apart. And I think it is a mistake to hold, as some metaphysicians do, that metaphysics has in its own right an absolute or ultimate veto over what we can believe and live on religiously. Religion can and should have the right to challenge metaphysics to adapt, if need be, to make the fit closer between thought and life. I will also candidly admit that St. Thomas and Thomists in general—with some notable contemporary exceptions—have not said enough to make clear how this is possible in their metaphysical conception of God as Pure Act and absolutely immutable, with no “real relation” to the world. Thomists must meet head on and explicitly the challenge of process philosophy of God and in particular of Hartshorne, whose philosophical theology is so much more fully developed than that of Whitehead.

Now to my examination and critique of how Hartshorne goes about achieving this worthy goal.

God as Changing

It is clear that God’s consciousness must register everything that happens in the world of creatures; it must be infinitely sensitive and receptive, if you wish, to all that is and happens. And since creation is free, this means that the contents of His consciousness must be contingently different, given this particular creation, than it would have been, given another creation. All Thomists, including St. Thomas, have no difficulty admitting that. It is a caricature of classical theism to claim that it holds that, since God’s existence is necessary (i.e. he is a necessary being in this sense), therefore everything in Him, including all the contents of His con-sciousness, is equally necessary and could not be other than it is. That would effectively cancel all freedom in God.

But here is my key objection. To say that every-thing contingent in our world makes a difference in the divine consciousness is not at all the same as to say that it makes a change in God. There is no necessary conceptual implication between making a difference and making a change. Making a change in God’s consciousness means that it would be first one way, then later in time another way; it would first be lacking this bit of knowledge, then later acquire it. But for St. Thomas (and on back to St. Augustine, who first made the point), the whole of time itself is part of this created world, is itself therefore created. God stands completely outside the whole realm of time. Time is not some overarching entity or frame-work including both God and creatures in some com-mon measure. God is simply not in created time at all, and there is no other.

Hence God in His eternal NOW is simply present to each event in our time, neither before or after it, but simply as it actually occurs. What God knows is em-bedded in the flow of created time, but in no way does that imply that His own process of knowing is also caught in the same flow of time within His own being. Our flow of time is based on constant physical changes or motion in matter. It makes no sense to say that God’s own inner action of knowing is locked into this process of physical (or any kind of created) motion. Whatever He knows from our world is simply registered in His consciousness in His eternal NOW, so that He is always the God who knows all this. Eternally His consciousness is contingently other, corresponding exactly to all that happens in our moving world, contingently different, but not first not knowing and later knowing any particular item. Total sensitivity to the tiniest event, to “every tear and every smile,” as Hartshorne rightly insists must be the case, is in this divine consciousness, but not first absent, then later present.

Thus there is no need to put change, successive temporal change, in God in order to ensure the contingency of His consciousness as regards our world. The only God there actually is, or ever has been, or will be, is the God that freely decides in His eternal NOW to create this world and sensitively registers in his consciousness all that goes on within it. To be contingently different than one could have been does not imply that one is first one way and later another; that is just one mode of contingency—our earthly one, plunged in successively moving matter as we are.8

It is a cause of constant surprise to me that pro-cess thinkers and Hartshorne in particular never seem to come seriously to grips with this conception of contingency in God, as contingently other but without successive temporal change. (We are leaving out for the moment the question of whether God’s perfection is greater because of creation than without it.). Of course, Hartshorne can answer that he has already argued the impossibility of any changeless knowledge in God, since God on this view would have to know the future from all eternity and so before it happens, and it is impossible to know the future, at least the free futures, before they happen.

He is entirely right that no one, not even God, can know the future before it happens (unless it is already predetermined in its causes), because a nonexistent not predetermined by some existent is simply unknowable. St. Thomas himself is adamant that actual existence is the necessary root of all knowledge. (Hartshorne also maintains—and I have no quarrel with him on this—that not only free personal agents but all actual entities have some tiny degree of unpredetermined spontaneity, hence none would be fully predictable.) But St. Thomas’s whole point is that God does not know what is future to Him. He knows events in time “in their presentiality to Him,” as he puts it, that is, as they are actually going on in their own present.”9 For those down in the physical time flow, one present or “now” excludes all others, hence in one of our present nows we cannot know a future one. But God is not locked into any of our nows. Hence it should never be said, as a good Thomist, that God knows what is future, i.e. future to Him; he knows only presents, each in its own proper present.

Hence I think it is incorrect, or at least misleading to say, as so many classical theists do, including St. Thomas, that God knows the future from all eternity (ab aeterno). This gives the impression that God somehow knows the future from way back before the creation of the world, since He is eternally existing and immutable. This is quite false. God does not know anything before the world exists. Since time itself is created, there is no “before.” God is always knowing—not from an eternal past, but from His eternal NOW, or, as I prefer to avoid misunderstan-ding, in His eternal Now—this world and all that goes on in it, as it is going on, but always as a finite whole, with a finite duration (at least in its beginning) if it has such. He is always present to this whole and all parts of it.

I also think it is incorrect (or at least misleading) to say, as many do, including Thomas at times, that God knows past, present, and future simultaneously, in a single simultaneous vision. The term “simulta-neous,” to my mind, is extremely difficult, if not im-possible, to detach from reference to our time flow, as though God knew all in one single moment or point of time. That would be absurd, because they are not in a single moment; neither is His knowledge-act. St. Thomas’s example of a person viewing a parade all together from above as opposed to from the reviewing stand limps badly. Even from above one could not see them all passing the reviewing stand at once.

Hence I believe that the only proper way to speak is to say “God knows (timelessly, or without tense) that such and such happens at time t,” but we cannot say when he knows it—today, tomorrow, or what-ever. He just knows all events in their presentiality, in or from the vantage point of his eternal NOW. This NOW, as St. Thomas says explicitly, includes all our nows. Hence to try to picture it as some simulta-neous “point” at which all lines from past, present and future become fused into one in God may well be a serious mistake. We just can’t say how “thick” or “thin” temporally God’s NOW is. It might, for all we know, be an infinitely distended motionless presence from inside of which all of history would appear just as it is in its unfolding. There would have to be indeed, in the divine consciousness, an irreversible internal order or sequence of mental contents or objects of knowledge, possibly something like an intelligible succession which would not involve physical change in God but only correlation with each point of our time—a divine “spiritual time,” if you will—but not at all our time flow. We must leave the exact how hidden in unimaginable mystery, saying only the minimum necessary of positive things about it, and carefully avoiding saying the wrong things.

In sum, I see no contradiction or incoherence in the position I have outlined above; it takes in all the infinitely delicate sensitivity of consciousness of Hartshorne’s God, but without the added baggage of change, which does import the new problem of embedding God in our physically based created time flow. There is just no one time flow for God and our world—probably not even the same one for angels (pure spirits) and our world. I will not even bring up the Relativity problem of which among the many relative time series God would be in, since there is no more absolute time.10

God as Infinite in Potentiality, Finite in Actuality

The dipolarity in Hartshorne’s God consists in this: God is infinite in His existence, which means in His inner nature in itself considered in abstraction from the actuality of His relationships with the ongoing world; but He is finite in His actuality, i.e. considered in the full concreteness of His ever-changing, ever-growing relations to the ongoing world. God’s knowledge of the world and His continuous recep-tivity, as He takes into himself all the values emer-ging from the experience of all His creatures, are always complete and perfect for that moment, hence always finite at anyone moment, but ever expanding as present moves into future. Thus at any moment in the ongoing process that is the universe God is unsurpassed and unsurpassable by any other but himself—but not infinite. All actuality, in fact, Harts-horne tells us, is necessarily finite, because determi-nate.11 And as He lives in this actuality of related-ness to us God experiences with us all our joys and triumphs and rejoices in them, and also feels our sorrows and sufferings and suffers with us in His own way as we go through them—except that He does not experience evil as such, because it is a negation, but gathers up only the positive in His eternal memory of values.

How then is God infinite? It can only be in his po-tentiality, as possessing inexhaustibly the power to deal with the world in unsurpassable wisdom and love down through infinite time. God’s infinity lies in His inexhaustible power, not in his actuality.

In assessing this interesting and original position, let me first consider the infinite side of this dipolarity. I have some serious problems here. Surely the infi-nite potentiality of God is not just a passive empty receptiveness but an active power. But an active power is potential only in relation to others, to what it will or can do for them. Inside the being possessing this power there must be the actual presence of a perfection proportionate to the fullness and perfec-tion of the power. A potentiality does not reside in nothing actual, just floating there somehow on its own. It must be based on something actually there in the real being of the agent. Pure active potentiality for both St. Thomas—and Aristotle before him—is a state of pure actuality in the agent, in full actual possession of the perfection from which flows its power; it is called potential only with respect to the actual communication of its power to others as its potential effects.

Furthermore, if God is the ultimate source of all being (at least the self-sufficient source of His own being, even for Hartshorne), then surely He must be an immense inner plenitude of actual being, of actual existence, which is in no way an abstraction. Having the fullness or highest degree of qualitative intensity of perfection, not being the sole possessor of it, is precisely what metaphysical infinity means for St. Thomas in the participation tradition stemming from Plotinus.12 Is this inner actuality in God, the neces-sary support of His power towards others, finite or limited in perfection and fullness? If limited, by what is it limited? If limited, does this mean there is some higher qualitative intensity of inner being possible? From what source would it derive, if not from the one God? Surely not from some other.

I am troubled, frankly, by what seems to be an implicit supposition behind Hartshorne’s conception of God: it is as though God’s consciousness were a totally extroverted one, as though the only life God had, His only active occupation that fills his consciousness positively, is His relation to what happens in this world distinct from Him. Does God then have no rich inner life, no actual inner experi-ence of joyous love given and received within himself? Here is where the Christian doctrine of the Trinity offers a beautiful complement to what no natural reason or philosophy can reach on its own. According to this revealed doctrine, God enjoys an immensely, infinitely rich inner life of self-communi-cating love, in which the Father, the Primordial Source, pours out His whole being, His identical nature, into the Second Person, the Son or the Word, in total ecstatic love, holding nothing back, and the two together then in an act of mutual love bring forth the Holy Spirit as their mutual love image.

Thus God already enjoys within himself, actually, an immensely rich, joyous experience of both giving and receiving love. All the very real joy and satisfaction the Triune God gets from our finite world can be but a tiny participation in this already existing fullness of experience and value. This is what God does inside himself/herself/themselves, and I find any serious recognition of this and its philosophical importance strangely missing both in Whitehead and Hartshorne. Now he might well answer that this is theology or faith, not philosophy. This is quite true, but at least philosophy should not deny or close the door to it prematurely, but leave the inner life of God untouched as a Mystery of life, actual life—allow God to have a dipolar actual consciousness, introvert as well as extravert. I see no good reason, then, for denying to God an infinite actuality of inner life, as well as the added finite actuality of His relations with us and our world. Otherwise the God of Hartshorne—and Whitehead—seems to be afflicted with a strange inner darkness, or unconscious state, with respect to himself, lit up only by looking down towards us and receiving satisfaction from us. Nor is it enough help to say He is occupied with thinking up all the infinite (?) possible patterns, or eternal objects, for guiding this world. This is still an exclusively extraverted inner life.

Now let us look at the finite side of the divine dipolarity. Here we touch upon one of Hartshorne’s most basic and I think fruitful insights in philosophical theology: the divine receptivity and relatedness to the world. Place must be found for it in any adequate philosophy of God, including Thomism. I think this can be done in an alert and open-minded Thomism not rigidly wedded to its own terminology, but the chances are Thomists would not have done so except under the vigorous prodding of Hartshorne himself, for which we must be grateful. I would like to express his insight somewhat differently, in more Thomistic terms, to avoid the difficulties I see in his strongly realist way of putting it.13

It must be admitted that the divine field of consciousness, in its relation to creatures, is not only contingent but finite in its content, because dealing with a finite number of finite beings, a finite world, which has been freely created and could have been other than it is. There is then a whole dimension of the divine reality which can be called finite. This is what Hartshorne calls the “finite actuality” of God. But I would insist that this finitude—and contingency—remains restricted to the field of the divine consciousness as relational ad extra, i.e. as looking towards creatures distinct from His own being. This relational intentionality of His intelligence truly relates Him to all His creatures and renders Him infinitely sensitive and receptive to all that is going on, especially to the responses of His free creatures. But all this remains within the field of His consciousness as relational, in the order of esse intentionale, as St. Thomas would put it, or being as known, as existing in the mind. This does not derogate from the infinity of God in His own real, intrinsic, or absolute being, or add on by that very fact any new finite real being to God. Thus, just as the immense multiplicity of the objective contents of the divine consciousness as knowing creatures does not destroy or cancel the simplicity of His own real being, so too the finitude of the creaturely objects of His consciousness does not annul the infinity of His own real being in himself. Finitude in the relational field of one’s consciousness does not entail finitude in one’s own real being, unless one has confused mental and real being. This is entirely compatible with traditional Thomism, I believe, though it has not always been clearly said by Thomists.

Secondly, the relational field of the divine intelligence with respect to creatures is contingently other than it would have been if a different world had been created, and reflects with infinite sensitivity—and receptivity—every least detail in this contingent world, as Hartshorne rightly insists and St. Thomas explicitly agrees. But, as we have argued above, this does not entail that a change, a temporal successive change, is constantly going on in this field, in God’s act of knowing the world. God in or from his eternal NOW is just directly present to each item in its place in our time flow, without being immersed in this created time flow itself. His consciousness is always contingently other because of His free decision in this NOW to create this world and not some other. He is always the God who in this eternal NOW rejoices over our responses to him in time, takes delight in the participations in His infinite goodness. There is not and never has been or will be any other real God than the one whose consciousness is contingently and finitely other because of this world he has freely decided to share His goodness with. But this does not imply a change going on in this consciousness, so that it is in its own real order first one way and then later another way, first empty of creatures then later—whatever that could mean—filled with them one by one.

Thus God in His relational conscious field, contin-gent and finite though it be, will not be surpassed—to use Hartshorne’s terminology—even by himself. But this finite field could have been surpassed by himself if He had decided in His eternal NOW to create differently. I see no good reason for, and many against, linking finitude and contingency in the divine consciousness, on the one hand, and temporal change on the other. Just because we cannot imagine what the inner phenomenology of divine knowing is like does not prevent us from affirming what it must be under pain of importing positive unintelligibility and incoherence into God—much worse than leaving his Mystery unpenetrated.

It will be noted, however, that I have given up the traditional Thomistic doctrine that God is not really related to the world. Although this can be defended in a very narrow technical sense, it is to my mind too misleading for the modern reader and leaves too much dangerously unsaid to be fruitful as a philoso-phical explanation of a religiously available God. Hartshorne himself once told me that if only Thomists would be willing to concede this point, his main battle with them would be won. I am glad to concede to him this victory. And if God is related at all to creatures, He must be, as Hartshorne rightly maintains, the most related of all, the supreme Receiver—but in the intentional order of relational consciousness, as eternally contingently other, not as changing.14

Divine Receptivity and Infinity: Are They Compatible?

We still have not met the full thrust of Harts-horne’s challenge. He maintains that the divine receptivity is not compatible with His actual infinity, and holding onto the actual infinity of God is the principal flaw in classic theism, such as found in St. Thomas. For him, the experiencing of value is reality. So when God is receptive of what goes on in our world, experiences the values we produce and gathers them up in His ever-growing eternal treasury of remembered value, such experiencing means a growth in the reality of God, by the constant addition of new values never experienced by Him before. Hence, although at anyone moment God’s actual reality and perfection is unsurpassed and unsur-passable by any other being, still the richness of His experience and hence actual reality is constantly growing as our world advances through time, so that He is constantly surpassing himself in the sum total of His actuality. Hence the divine actuality must be finite at any given moment in time, but ever growing. Infinite divine actuality would deny receptivity to God, and if He is receptive then His actuality cannot possibly be infinite. One most choose; and divine receptivity is far more important for the religious conception of God than is infinite actuality or Pure Act.

We have already seen how the contingency and finitude of the contents of the divine field of con-sciousness in relation to creatures, while it matches exactly every item in our time flow, does not imply that there is a time flow or change within God himself, only that his relational consciousness is eternally different because of all that is in our world, but not first one way and later another. We will not go back over this point.

But what about the question whether the divine actuality in God himself is greater because of His experience of our responses to Him and the values we produce? This is the core of the problem. In Hartshorne’s system, where God is not the ultimate source of all being, all perfection, where the relation between himself and creatures is therefore not one of participation, and where God does not know what we are doing by doing it with us actively, this position certainly must follow. God is constantly experiencing something new coming from us that does not come from Him as a shared participation in His own perfection.

But in a participation metaphysics like that of St. Thomas the situation is not the same. God already possesses an actual infinity of inner life and joyous experience within himself. He then takes delight in sharing His own fullness of inner life of self-commu-nicative love with the immense variety of His freely chosen creatures, and takes delight in receiving their responses—all in His eternal NOW. But all that he receives from us is only a tiny finite image or participation of his own already infinite fullness or qualitative intensity of joy experienced in His own inner life. So there is indeed a vast multiplicity of new finite determinations of the divine joy returning to Him from his participating images. But these never add up to anything approaching a higher qualitative intensity of life and perfection than the infinity He already possesses.

Even though St. Thomas himself never says this, and probably would refuse to say it, I see no really decisive metaphysical difficulty in saying that God knows, experiences, and enjoys a whole multiplicity of genuinely novel finite modalities of participation in his infinite goodness, so that God’s experience is precisely different in His eternal NOW because of us than it would have been otherwise—different in His relational experience turned toward us, and thus richer in new determinate ways of enjoying new finite participations in His already infinite life and joy. But I do not see that an indefinite number of new sharings in God’s already infinite richness of life are any threat to His infinity at all—as long as they are partici-pations, deriving entirely from His gifts to us and His working supportively with us. Similarly I do not see that His own new determinate modalities of enjoyment from His creatures are any threat to His already infinite interior enjoyment of His own life. Infinity plus one finite, or any number of finites within the order of participation, even within God’s own consciousness, does not negate either side, as long as the infinity is of a personal kind that is able to share its own riches freely and take delight in this sharing. In a word, the point is that sharing in finite modalities is no threat to the infinite fullness of Source, especially when this infinity of perfection is precisely of a personal kind, where perfection must mean in fact the fullness of altruistic, self-communicative love, where the Infinite One is an Infinite Lover. But that is precisely what God is.

I do not think Thomists are careful enough in pointing out that all the perfections of God, Pure Act and all the rest, must always be controlled by their central rooting in a Personal Being. The Pure Act of Existence, Infinite Perfection, Immutability, etc., when taken in the concrete in their one existing instantiation, are not to be thought of in some purely objective, impersonal way, like the smoothly rounded motionless block of matter Parmenides images as Being. They must be precisely the highest qualitative intensity of personal life. Being at its supreme level is through and through personal; that is what it means to be without restrictions, and the fullness of personal life is precisely the life of self-communi-cating love, as revealed in the Christian Trinity, a life not of static contemplation, but of infinitely intense intercommunication between persons, circuminces-sio, as the Scholastic theologians put it (a mutual indwelling and “circulation” inside each other, so to speak), in a word, the life of interpersonal love that is equally giving and receiving, self-communication and receptivity. That is what it means to live personally in the full sense, and a fortiori at an infinite level. Any metaphysical theory that would interpret the attributes of God in such a way as to diminish or abolish the personal character of their subject is off the track from the beginning. The person, St. Thomas says, “is that which is most perfect in all of nature”; hence it must control and adjust all the other attributes to itself—they must not dominate and distort it.

This is indeed an expansion of Thomism. But if a careful synthesis is made of (1) difference in the relational consciousness of God toward us, rather than change, especially in the sense of our temporal flow; (2) participation of all real being both in existence and power from the One Source, so that all that comes back to the Source never rises to a higher qualitative level of perfection than the Source; (3) the active working of the divine power in all creatures, doing with them all they do, knowing what we are doing by how we let His active power flow through us; (4) an infinitely rich interior life of His own in God in the ecstatic self-communicating love within the Trinity, so that any finite satisfaction or joy God receives from us is but a tiny participation in this already actualized inner infinity—if these are put together carefully, I say, I think we can generate a metaphysics of God and creatures that is a legitimate expansion of the key insights of St. Thomas (or what I might more safely call a “Thomistically inspired” philosophy of God). And expand in some way like this I think Thomists must, if we are to meet the profound and rich challenge of Charles Hartshorne. I am deeply moved and inspired by the basic insights motivating his dipolar natural theology; but I feel he puts it together the wrong way as a technical metaphysical system, with too many blind spots regarding change, actual infinity, and participation, resulting in too many unnecessary paradoxes.

Postscript on Personal Immortality

Let me say just a few words on Hartshorne’s view that personal immortality—an everlasting life of the individual person with God after death—is neither possible nor desirable. That it is not possible derives from Hartshorne’s process theory of the personal “I” as not the perdurance of the same concretely iden-tical entity, but a society of successive actual enti-ties bound together by various bonds of inheritance, etc. I do not wish to enter here into what would have to be a long discussion. Let me just say that I, with many others, do not accept this process view, either in Whitehead or Hartshorne, as adequate to the reality we know as persons and selves. But let that pass.

What I find more interesting and challenging, with its own nobility of conception, is the idea that I should not even want or need an unending individual immortal life in personal communion with God. His treasuring up in total and unsurpassable detail all the lived values and achievement of my life, my unique personality, etc., for His glory and loving satisfaction, is all I need and should desire. Anything else would be an excessive self-centered absorption in my own little life for itself, instead of living for God and His service.

The one great and inconsolable flaw I find in this letting go of the self is this: I will never—and no created person will ever—fulfill the great unrestricted dynamism of my spirit, constitutive of me as intellec-tual and willing being, as a person, to know God face to face, to experience His infinite goodness and the marvel of His self-communicating love within the Trinity, which I would so long to share—and in which He has lovingly invited me to share, according to Christian revelation. This present life in the present body is such a chancy and incomplete journey of “seeing darkly in a mirror,” as St. Paul puts it, that it could not possibly satisfy this immense longing to see the Truth and commune with the Good as it is in Itself, no longer through the imperfect and irre-trievably blurred mirror of finite, especially material, creatures.

Yet Hartshorne tells us that we can never possibly come to know what he admits should be the Great Love of our hearts, never get to penetrate within the wonder of God’s providence over the universe, even the depths of the universe’s own created wonder and richness—in a word, that I should be radically frustrated with no hope of assuagement in the deepest longings of my mind and heart. To this I say, “No sale.” This does not appear to me as self-centeredness contrary to my nature, to the way I was made by my Creator, but the total centeredness in God for which I have been destined by the con-stitution of my very nature as dynamically finalized, drawn toward God, by Him. I cannot look on radical frustration of the deepest innate drive of my nature, of which I am not the cause, as noble unselfishness but as inexplicable, irrevocable frustration. The wondrous mystery of final face-to-face communion with God, my Source, is that the two extremes are brought together here by God: my total giving up of self-centeredness to put my true center in God turns out also to be my most authentic self-fulfillment. We are indeed finite in our actuality, and in many respects in our potentiality. But let us not set the limits of our finitude too low.

To sum up this whole paper, I have been more challenged, and learned more, from the profound and authentic insights of Charles Hartshorne than probably from any other living natural theologian; but I must disagree with many of his metaphysical formulations of these insights. They leave strewn in their wake too much priceless and irreplaceable china from the classical tradition.

Notes

1 I have developed this point at greater length as applied to Whitehead in my book, The Philosophical Approach to God (Winston-Salem, NC: Wake Forest Univ., Philosophy Dept., 1979). Chap. 3: “Christian Theism and Whiteheadian Process Philosophy: Are They Compatible?”; see esp. pp. 67-86.

2 See, for example, Hartshorne’s Omnipotence and Other Theological Mistakes (Albany: SUNY Press, 1984).

3 Summa contra Gentes, Book III, ch. 68 (Pegis trans. On the Truth of the Catholic Faith); De Veritate (On Truth), quest. 9, art. 2.

4 Summa Theologiae, I-II, q. 9, art. 6, ad obj. 3: “God moves man’s will, as the Universal Mover, to the universal object of the will, which is the good. And without this universal motion man cannot will anything. But man determines himself by his reason to will this or that, which is a true or apparent good. Nevertheless sometimes God moves some specially to the willing of something determinate, which is good; as in the case of those whom He moves by grace, as we shall state later on.” Cf. On the Power of God, q. 3, art. 7. ad obj. 13: “The will is said to have dominion over its own act not by exclusion of the First Cause, but because the First Cause does not act on the will in such a way as to determine it by necessity to one object, as it determines natures, and therefore the determination of the act remains in the power of the intellect and the will.” See also Sum. Theol., I-II, q. 10, art. 4: “As Dionysius says, it belongs to the divine providence, not to destroy, but to preserve the nature of things. Therefore it moves all things in accordance with their conditions, in such a way that from necessary causes, through the divine motion, effects follow of necessity, but from contingent causes effects follow contingently. Since, therefore, the will is an active principle that is not determined to one thing, but having an indifferent relation to many things, God so moves it that He does not determine it of necessity to one thing, but its movement remains contingent and not necessary, except in those things to which it is moved naturally.”

5 Cf. Anton Pegis, “Molina and Human Freedom,” in Gerard Smith (ed.), Jesuit Thinkers of the Renaissance (Milwaukee: Marquette Univ. Press, 1939), pp. 99 ff.; Gerard Smith, Molina and Freedom (Chicago: Loyola Univ. Press, 1966).

6 The finest article I know that brings out with unam-biguous clarity and textual support St. Thomas’s doc-trine of the non-determining causality of God on the human free will—in respectful but firm opposition even to his own Dominican brethren of the Bañezian School—is that of the distinguished Italian Dominican metaphysician, Umberto degl’lnnocenti, O.P.” “De actione Dei in causas secundas liberas iuxta S. Thomam.” Aquinas 4 (1961), pp. 28-56.

7 See the critique by Colin Gunton, Becoming and Being: The Doctrine of God in Charles Hartshorne and Karl Barth (Oxford Univ. Press, 1978). pp. 57-58.

8 I only recently discovered that the same critique of Hartshorne’s position on this point has been clearly and incisively made some time ago by Merold West-phal, in his very insightful article in defence of classi-cal theism against the arguments of Hartshorne, “Temporality and Finitism in Hartshorne’s Theism,” Review of Metaphysics 19 (1965-66), pp. 550-64.

9 Sum. Theol., I, q. 14, art. 13.

10 I understand Hartshorne feels he is now off the hook on this thorny point over which he has received so many objections (including from Lewis Ford) because of the startling new development in physics deriving from Bell’s theorem, showing apparently that subatomic particles, once joined together, are forever joined in complementary properties, res-ponding to each other’s changes instantaneously across space faster than the speed of light, thus suggesting that the physical cosmos is somehow a space-(and time-?)transcending whole behind the scene of space. This may help him, but it is not clear yet that there is but one common time for this whole—it might transcend time entirely as it does space in certain limited respects.

11 See Hartshorne’s A Natural Theology for Our Time (LaSalle: Open Court, 1967), p. 24: “Only potentiality can be strictly infinite . . . actuality . . . is finite . . . .”

12 Cf. W. N. Clarke, “The Limitation of Act by Potency: Aristotelianism or Neoplatonism?” New Scholasticism 26 (1952), pp. 167-94.

13 See Chap. 3 in my book, The Philosophical Approach to God (note 1), pp. 87 ff.

14 See the reference in note 10 above.