AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From Thomist, 40 (1976), 32-60. This replies to Kai Nielsen’s “Talk of God and the Doctrine of Analogy” in the same issue. It was reprinted in Clarke’s Explora-tions in Metaphysics: Being-God-Person, University of Notre Dame Press, 1995, 123-149.

Anthony Flood

May 13, 2010

Analogy and the Meaningfulness of Language about God:

A Reply to Kai Nielsen

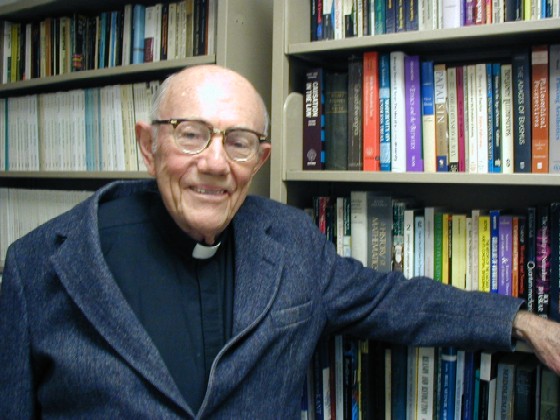

W. Norris Clarke, S.J.

I must say that I feel considerable sympathy with Professor Nielsen in his difficulties in making sense out of the Thomistic doctrine of analogy as a device for rendering language about God meaningful. In fact, for many years now I have been struck by the constantly recurring phenomenon of philosophers outside the Thomistic tradition trying to understand the doctrine of analogy as applied to God and being quite sincerely baffled in their attempts to see how it can do the job assigned to it. When this occurs so often, there is a good chance that the fault is not all on the one side. And, to be honest, I do not think Professor Nielsen gets adequate help from either Father Copleston or Professor Ross. He may not get adequate help from me either, but I would still like to try, since I consider the issue such an important one.

The main reasons for the obscurity surrounding the Thomistic theory of analogy seem to be three. First, historically, St. Thomas himself, ordinarily such a systematic thinker, for some unexplained reason was never willing to pin himself down to any one consistent terminology or structural analysis of the logical form of analogy. He simply used it, very sensitively, but without any full dress explanation of what he was doing. When Thomistic commentators after him have tried to pin down the theory more precisely and technically, they too often have fallen into the straight jacket of Cajetan’s oversimplified and restrictive systematization, in which the structure of proper proportionality is understood as a four-term proportion, a structure that St. Thomas himself quietly abandons as not adequate by itself after his early work, De Veritate.1

Secondly, doctrinally speaking, Thomists tend too often to omit in their formal analyses of analogy the indispensable metaphysical underpinning that alone justifies the application of analogy when one of the terms is not known directly in itself. No purely logical or semantic analysis of the structure of analogous concepts can supply this extra-logical component. In addition, Thomistic commentators for the most part do not bring out clearly enough—if indeed they accept the point at all—the fact that analogy does not lie so much in any formal structure of concepts themselves as in the actual lived usage of meaningful analogous language, found only when the so-called analogous concepts are used in judgments.2 In the light of the above comments I would like to see if I can shed some light of my own on Professor Nielsen’s difficulties, so that at least the authentic and essential points of disagreement may be brought more clearly into focus and allow more fruitful dialogue thereon than usually seems to be the case in this elusive question of analogy.

Objections of Professor Nielsen

The three most crucial objections of Professor Nielsen against the explanations of Copleston and Ross seems to me to be the following.

(1) The first concerns the distinction made by Copleston between the “subjective meaning” of an analogous term, i.e., our understanding of the meaning as drawn from instances in our experience, which he admits is anthropomorphic, and the “objec-tive meaning,” i.e., the objective reality referred to by the concept as found in God and affirmed of him, even though we do not know just what this is like, but only point to it in the dark, so to speak, and for good reasons, since it is an infinitely higher mode beyond the direct grasp of our experience and concepts. But the trouble here, as Professor Nielsen points out, is that, since we have no access to this objective meaning as it is verified in God, which is quite different from the subjective meaning drawn from our experience, this so-called objective meaning is vacuous, empty of meaningful content for us who are using the term. And the gap between the two meaning-contents indicates that the concepts predicated in each case are not the same, though the same word is used; hence there is equivocation.

(2) The second concerns the very meaning of an analogous concept in itself. At the heart of every analogous concept, Professor Nielsen insists, there must be “a common core of meaning,” which in turn necessarily implies that this core of meaning must be univocal. “Common core of meaning” and “univocal” are co-extensive and convertible terms. No merely formal structure of isomorphic relations can supply such a common core.

(3) Third, Professor Nielsen points out that there is no way of confirming or verifying the meaningful-ness or truth of what is analogously predicated of God, since there is no way of verifying or falsifying it from experience or by any kind of testing for consequences.

Most of my reply will be directly concerned with the objections to Copleston, since the objections to Ross seem to me merely a more technical application of the same basic difficulties. And, besides, I agree with much of Professor Nielsen’s dissatisfaction with any attempt to lay out analogy in some formal logical structure. No isomorphism of formal relations can supply for intrinsic similarity in content between the sets of relations compared. Since I do not think it feasible to separate out the answers to the three objections, for they all involve the same roots, I shall give my own account of how analogy works and pick up the objections along the way at appropriate points. I will not give any distinct answer to the third objection. Many have handled this already. And there is simply no testing from experience or from consequences of predications when one is discour-sing about the attributes of God. The only testing is the metaphysical exigency of intelligibility itself: predications about God must have both meaning and truth if our own world is not to fall into unintel-ligibility. They are all metaphysical musts flowing from the primary must of the causal bond itself. Hence I will divide my exposition into three main sections: I. Must Analogy Be Rooted in Univocity? II. The Extension of Analogy Beyond the Range of Our Experience. III. The Application of Analogy to God and Its Metaphysical Underpinning.

I. Must Analogy Be Rooted in Univocity?

As we read through Professor Nielsen’s criticism of both Copleston and Ross, we notice one crucial assumption functioning over and over again, at first more or less implicitly, then finally surfacing with full explicitness. It is this: if there is to be any genuine similarity within difference in the various predications of an analogous term, then this similarity necessarily involves some “common property” or attribute, even if only a relation, which holds in all applications; now the presence of such a common property necessarily involves a “univocal core of meaning.” Analyzing one of St. Thomas’s descriptions of knowing (it should be noted, however, that this does not apply to all knowing but only to the knowing of another than oneself), which runs, “the possession of the form of another as another, according to one’s natural mode of possession,” Professor Nielsen comments:

This last qualification presumably gives us the difference which keeps the predication from actually being univocal. But it remains the case that on the assumption (questionable in itself) that Aquinas’ account of knowing is intelligible, it is true that in all cases of ‘knowing’ there is a property that remains common to and distinctive of all these uses. That is to say, we could construct a predicate signifying the res significata of ‘knowing’ that would be predicated of all cases of knowing. This would be a univocal predication. (p. 50)

In other words, whenever there is a common pro-perty predicated, there must be a univocal core of meaning. Hence even the qualifying phrase added by St. Thomas, “according to one’s natural mode of possession,” must leave intact the univocal core of meaning, “possession of the form of another as another.”

Here is the central and clear-cut point of conten-tion between Professor Nielsen and the Thomistic tradition in the very meaning of analogy itself. Thomists would admit—though a few, like David Burrell, seem unduly squeamish about doing so—that in some significant sense there must be some common core of meaning in all analogous predications of the same term, for otherwise it could not function as one term and concept. But they insist, on the other hand, that this common core of meaning is not therefore univocal, but remains analogous, similar-in-difference, or diversely similar. If it is any consolation to Professor Nielsen, his objection is exactly the same as that brought against Thomistic analogy by Duns Scotus and William of Ockham shortly after the time of Thomas himself. For them the sufficient requirement that a term be univocal is that it be able to function as a middle term retaining the same meaning in both premises of a syllogism, enough to avoid equivocation. An analogous term was for them really a verbal unity of two distinct, though related, concepts, and if used in both senses in the same argument would introduce a fourth term and invalidate the argument.3

Yet this is definitely not the Thomistic under-standing of univocity and analogy. The difference in approach between the two positions might be summed up thus: The Scotus-Ockham analysis is geared primarily to the demands of deductive reasoning and the logical functioning of concepts. It also takes the word and concept as the fundamental unit of meaning, which remains intact in its own self-contained meaning no matter how it is moved around as a counter in combination with other concepts, including its use in a judgment, which is interpreted simply as a composition of two concepts, subject and predicate, without change in either. The Thomistic analysis is geared much more to the actual lived usage of the concept in a judgment, interpreted as an intentional act of referring its synthesis of subject-predicate to the real order, as it is in reality. Hence it tends to look right through the abstract meaning of the concept to what it signifies, or intends to signify (intendit significare), in the concrete, and so adjusts the content of the concept to what it knows about its realization in the concrete. The difference in pers-pective—and in theories of the relation of concept to judgment—leads to quite different conclusions, which I think are considerably more than a merely verbal dispute over different terminologies for the same thing, though there is some of that hanging like a cloud over the scene too, causing the opponents to pass each other in the fog without meeting.

Let me explain now how I think Thomistic analogy actually works, building it up genetically from its actual origin and use in living language. I take it as understood that from now on when I speak of analogous terms and concepts I am referring only to what Thomists identify as properly and intrinsically analogous terms, i.e., those that are intended to express a proportionate intrinsic similarity found in all the analogates (hence not analogies of the so-called “extrinsic attribution,” such as “healthy” applied to man and to food, which is not designed to express similarity but some relation of causality, belonging to, etc.). Such intrinsic analogies are found in terms like “knowledge,” “love,” “activity,” “unity,” “goodness,” “being.”

We construct and use analogous concepts in our language-life to fit occasions wherein we cannot help but use them. This occurs when we notice some basic similarity-in-difference, or proportional similarity, across range of different kinds of subjects (or on different levels of being, of qualitative perfection), such that the similarity we notice does not occur in the same qualitative way in each case but is noticed to be found in a qualitatively different way in each case. When we form a univocal concept, on the other hand, we pick out some similarity, usually some form or structure or quantitative relation, which we judge or notice to be found with significant qualitative variation in each case, usually falling within the same species or a genus with closely related properties. In such a case we notice that, even though a few examples are needed to get started, the meaning content, what the term objectively signifies, once grasped, remains neutral, indifferent, unchanged with respect to any further instances. Such a content is thus quite well defined, determinate, and fixed.

Not so with an analogous concept. The similarity we notice here is not some one thing or characteristic that remains exactly the same in all cases, except for some new additional note being added on each time from the outside. It is rather that the similar proper-ty itself is more or less profoundly and intrinsically modified in a qualitatively different way each time, so that through and through the whole property is recognized as at once similar yet different (not just found in some new instance that in other ways is different). An analogous concept is not a compo-sition of one part exactly identical and another part different, as Scotus, Ockham, and Nielsen seem to imply; rather it is an indissoluble unity where the similarity itself is through and through diversified in each case. As a result there is quite a bit of “give,” flexibility, indeterminacy, or vagueness right within the concept itself, with the result that the meaning remains essentially incomplete, so underdetermined that it cannot be clearly understood until further reference is made to some mode or modes of realization.

This leads us to discover one of the most remar-kable and distinctive features of analogous concepts, especially the ones of broadest range: it is in fact impossible to define what we mean by an analogous concept, to grasp the similarity involved, except by actually running up and down the known range of cases to which it applies, by actually calling up the spectrum of different exemplifications, and then catching the point. The similarity involved cannot be isolated from its qualitatively diversifying modes and expressed by itself clearly, as it can be in the case of a univocal concept. It can indeed be caught or recognized by an act of intellectual insight as we run up and down the scale of examples. It can be seen, and shown forth by our meaningful linguistic behavior, as Wittgenstein would say, but it cannot be said or expressed clearly by itself. Or, if you wish, it can be said by framing one linguistic term for use in all cases, but the meaning of the term cannot be grasped at all clearly without actually calling up a diversified range of cases. The meaning of the term, therefore, must be completed and made determinate in each case by reference to some concrete qualita-tive mode. That is why the notion always contains within it, at least in an implicit way—which can easily be made explicit, as St. Thomas does in the example of knowledge—the parenthetical indication (like a kind of metalinguistic instruction or warning) that the property in question will be present in each case “according to the mode proportionate to the nature of each.” Yet the concept itself, as an abstract predicate by itself, fit to be used in many different predications as somehow the same one concept, does not mention or contain within its expressed content any of these particular modes in any of its predications, but is understood as transcending them all. Otherwise, it is clear, it could not be used to refer to any other instance with a different mode. How-ever, when this indeterminate abstract concept, unified as such, is actually used in a concrete judg-ment, its meaning, as understood in the whole con-crete act of knowing that is the judgment, then molds itself or shifts to take on the particular determination of the case in hand, while at the same time con-tinuing to recognize the intrinsic proportional similarity-in-difference of this instance with all the others in the range outlined by the concept. This is the point of the very astute remark made by Gilson long ago, that “‘analogy’ for Aquinas refers to our ability to make the kind of judgments we do,” that it is to be explicated “on the level of judgment “and “not of concept “alone.4 Analogy is to found and understood on the level of the lived use of concepts and terms, not in any formalizable logical structure of the concept in itself. Thus when I understand in an analogous way a proposition like “is intelligent,” what I mean is, “exhibits or realizes in this different but still sufficiently similar way the same similarity-in-difference which I have already noticed running through a certain range of cases, so much so that I feel justified in expressing this case by the same analogous term as the others.”

I have laid special stress in the above on the im-portance of the lived use of concepts in judgment, because it is not always brought out sufficiently by Thomists, and is one of the distinguished marks of the approach of St. Thomas when compared to that of Scotus and Ockham. A Thomistic analogous term does indeed contain a certain genuine unity, though heavily laced with indeterminacy at its core, enough unity to function logically quite like a univocal term. And, of course, if one considers an analogous concept from a comparative or negative point of view with respect to other concepts, it is quite determinate in what it excludes from consideration, in how it delimits its whole range from that of other concepts. But the point remains that when looked at in what it positively includes within its range it cannot express clearly by itself the similarity in isolation from the differences. When it tries to do so through so-called definitions it can only call up as paraphrases other equally analogous and indeterminate terms, which themselves require reference to a range of diverse examples in order to be meaningful. And whenever it tries to become too precise, it contracts to become identical with just one of its modes and loses its analogical function.

Let me illustrate what I have been saying above by taking the same example used by Professor Nielsen, that of knowledge, defined by St. Thomas as “the possession of the form of another as another, according to one’s natural mode of possession.” Let us say that we have already recognized as included within its range of proper instances the dim know-ledge through touch of the environment around it by an oyster or snail; the more complicated integration of visual, tactile, and audible sense images by a dog or other higher animal; the intellectual insight of man into justice or the inner law of operation of a typewriter or Einstein’s Theory of Relativity; the Zen master’s empty, imageless, supra-conceptual aw-areness of reality; the mystic’s awareness of God in the “fine point of the soul “beyond all concepts and faculties. All are judged to be genuine though highly different instances of knowing. Now suppose we try to say or describe just what is the similarity amongst all of them, in itself. And suppose the person to whom we are trying to describe it says “I don’t want you to do it by examples; just tell me what it is in itself.” What could we possibly tell him that could capture the commonness by itself? We can only run through the spectrum of examples on different levels and then appeal to the person’s own experience. “Do you know what I mean? Do you get the point?”

Professor Nielsen, it seems, would like to insist: “But there is a common univocal core: possession of the form of another as another. . .” Yet suppose we try to apply this even to only two cases, such as a dog’s “possession” of the “form” of a typewriter in the mode of a visual image of its external shape and color, compared with a man’s “possession” of the “form” as intellectual insight into the inner law of operation of the machine. What in the world does “possession” mean here? How can we describe it in itself? Is it like the possession of a marble in one’s pocket? No. Or having a cast in one’s eye? No. Is it possessing a visual image in consciousness? Aside from the problem of defining “consciousness,” this is one example, but not one that adequately circum-scribes the meaning, since having an intellectual insight into the intelligible form or law is vastly different, even though somehow similar—it is impossible to specify just how. The same difficulty would occur in trying to explain “form.” The only thing one can finally do is call up the whole range of examples and ask, “Don’t you catch the point? Do you see what I mean?” This is not an evasion; it is precisely the intelligent (in fact, the only effective) way to do it. The same with other analogous concepts, such as unity, activity, love, goodness, power, perfection (imagine trying to describe precisely what is similar in all instances of activity or perfection). In a word, although one can indeed say that in some true sense (analogous) there is a com-mon core of meaning in an analogous concept, it is nonetheless clear that the concept functions quite differently—if we look at it from within as used, not just from without as a logical counter in an argu-ment—from a univocal concept with its common core.

This leads me to one more distinctive character-istic of the analogous concept which I think it most important to mention, since it too is frequently not made explicit by Thomist commentators. What kinds of things, or aspects of reality, or properties are thus amenable to, even necessarily require, expression through analogous terms? As I see it—and I am willing to defend this, even though it is not commonly mentioned—there is only one “dimension” of reality or “kind” of property that is capable of truly anal-ogous expression: this is the realm of activities or dynamic functions, what we might call “activity properties” understood in the widest possible sense (plus, of course, the opposite correlative properties of receiving, being acted on, etc.: loving and being loved, causing and being caused are equally analogous). All such properties are expressed originally and primarily by verbs, not nouns, or are in some way reducible to verbs. Analogous terms can of course be nouns, but then the noun presupposes the verb—e. g., it signifies a subject, but as the doer of such and such an action, which aspect alone is made explicit (knower, lover . . .).

The reason why activity properties are such fit candidates for analogous expression is that the same general “kind” of activity can be performed quite differently by different kinds of agents or subjects without destroying the similarity-in-difference of the activity aspect itself. This is not true of forms, structures, quantitative relations, and the like, which are not thus elastic in their realizations. Different kinds of things in the universe, different levels of being, are not like each other in their essential specific forms or essences considered statically. But they are proportionally alike in their modes of activity, in their dynamic functions. Different forms themselves can only be compared as alike insofar as they are forms or structures for similar actions. If there is any formal structure to analogous concepts, it is not a strictly logical or formal structure, but the structure of an activity situation: an analogous term expresses this general kind of activity x, recognized as carried on in one distinctive proportionate way by subject a, in another distinctively different propor-tionate way by subject b, etc. The subjects and modes of acting are quite different in each case; the activities themselves are recognized as propor-tionately similar, similar-in-difference, although it remains impossible to state just what this similarity is apart from its range of varied modes. Let me add that if the term “activity “itself here is allowed to expand to its full analogous breadth of illuminative meaning, existence itself then not only can be described but is uniquely appropriate to be described as the most radical kind of activity or act, the act of “presencing.” This is the Thomistic analogous notion of being itself: “that which has, or exercises, the act of existing.”

II. The Extension of Analogous Terms Beyond the Range of Our Experience

So far we have been analyzing how analogy functions within a range where all the main levels of exemplification lie within our experience, hence where the different modes can be directly known to us. The next phase of our investigation, crucial for the application to God, concerns the extension of analogous concepts beyond our present range of known examples, i.e., the formation of “open-ended” concepts whose range extends indefinitely beyond our present experience, at least in an upward direction. The ranges of analogous concepts can be roughly classified as follows: (1) those having a ceiling but no floor (no lower limit) in their applica-tion: terms like physico-chemical activity, whose up-per limit is biological activity, or perhaps conscious-ness, but that extend downward to unknown depths of matter still hidden from us and perhaps very strange indeed compared with what we know; (2) those having both floor and a ceiling, say, biological activity, or sense knowledge, limited by the non-living or unconscious below and intellectual know-ledge above; (3) those having a floor but no ceiling: intellectual knowing, love, life, joy, etc.; (4) those having neither ceiling nor floor: the all-pervasive “transcendental properties” applicable across all levels of being, such as being, activity, unity, power, intelligibility, goodness (in the widest sense). Our special concern will be with numbers (3) and (4), as alone applicable to God.

How in general do we go about opening up an analogous concept beyond its presently known range of examples? Let us take the example of knowing. Suppose we reflect on how remarkably diverse are the modes we already know, and how impossible it is to deduce from a lower level what a higher level will be like; it then appears to us, when reflecting on the analogous meaning of knowing, that we have no good or decisive reasons for closing off its possible range at the level we know; in fact, there is some plausible suspicion that there may be higher kinds of intelligence on other planets or perhaps even beyond all corporeal entities (not yet God). We decide we should remain prudently open to the possibility of higher intelligence trying to communicate with us through some kind of signal. We have no idea what kind of communication or signals—they would not even have to be through material signs but might be by direct telepathy or thought-communication—or what the mode of intelligence involved might be like or how it might function in itself, even when not attached to a body. Yet it makes perfect sense, and in the concrete it is quite easy—we are actually doing it already—to open up the range of meaning of what we now experience and understand as intelligence to include in expectancy some possible level at present quite unknown and uncharacterizable by us. The new extension of the term, though empty of any precise content describable by us now, is not simply empty. It gets its new and very useful content of meaning from its place on an ascending (it might also be des-cending) scale, which serves as guide for evaluation assessment (respect, awe, fear, caution, etc.). Such a role as guide to evaluation procedures, and their practical consequences, is an indispensable one for our concrete life of the mind in the midst of a reality that is always partly known, partly concealed in relation to us.

Another example arises from the new scientific interest in para-psychology and psychic phenomena of various kinds. There is widespread talk of some new kind(s) of force that produces effects in the material world, yet seems to operate in ways thus far unknown to us and is quite different from the other physical forces we know—“psi-forces,” some call them. They may be a new kind of physical radiation, or more probably psychic energy fields, or what have you. The point is that we quite readily enlarge the notion of force to make room for the possible discovery of a new mode, concerning which we can say nothing clear as yet, not even that it really exists. It may be objected that there is a univocal core in all description of such forces, in that they produce observable effects in the material world. There may, it is true, be one element of their definitions that has a univocal cast: the material effects produced. But the notion of force does not mean the effects produced. It means the power producing such effects, and as long as this central part of the meaning is variable in its mode the meaning must remain analogous.

In both of the above, and many other possible examples, in order to extend the range of an analogous concept we must “purify” its meaning-content, what it explicitly signifies, making it indeterminate enough so that its range of application will not be restricted within present limits. If we judge that this cannot be done without a violent and arbitrary wrench in the meaning that renders the term no longer comfortably serviceable enough, we judge the proposed extension inviable, too confusing, and devise an entirely new term to express the additional range of cases presumed to exist. This is a matter of good judgment, of a sense for successful living language, not a matter of the logical structure of concepts.

It is within the context of this extension of an analogous concept to a new application whose mode of realization is unknown to us that the traditional distinctions arise between “objective meaning” and “subjective meaning” (Copleston), the res signifi-cata, or the objective property signified by the term, and the modus significandi, or the modes by which we express to ourselves this property (St. Thomas), and other similar semantic devices. There is unfortunately much confusion in terminology here (and not infrequently in thought too, I fear), and I am not happy with either of the above ways of trying to spell out the same general point. St. Thomas’ way is clear enough in itself—though often misunderstood, as it clearly is here by Professor Nielsen—but is so narrow in scope as he uses it that it does not do the entire job that has to be done. Copleston’s way is, I fear, open to serious misunderstanding and seems to me to be inadequate to its task. So let me first state the job to be done, and how I think it best to express it, and then return to assessing the two sets of distinctions mentioned above.

In such a context of using analogous language, we must separate out the following: (1) the res signi-ficata, i.e., the “thing” or common property signified, which is what is actually predicated in each case, whether previously known or not. Its meaning-content as expressed in the analogous concept is deliberately or systematically vague and indeter-minate, not restricted to any of its modes so as to be truly predicable of all cases. (It does not mean, by the way, the actual concrete referent of this predicate in a given judgment, although the terminology of “thing”—res—has misled some into thinking so.) (2) The real modes, or modes of being, in which this common objective property or attribute is understood to be realized in given applications, as we apply the term in concrete complete acts of knowing in the judgment. These modes may already be known to us, as the animal and human modes of knowing, or they may as yet be unknown to us, in which case we intend to signify what is there in the concrete but through a vague and incomplete act of knowing. Or, if you wish, we intend to refer to what is really there, but through a vague and incomplete mental sign, recognized as such, although we do recognize clearly that we are referring to a mode different from the others we know. These modes, however, are not part of what is actually predicated by the abstract analogous predicate itself, as is (1) above, although we understand the indeterminate content to take them on in the concrete, as we actually use the term.5 (3) The modes of our understanding of the res significata, which are the best known modes of concrete realization of the common property, considered as ways or media through which we first come to lay hold of the meaning of the property and upon which we fall back as the clearest examples when we wish to evoke its meaning for ourselves anew—since, as we noted above, it is always necessary to call up some examples across a range in order to grasp or recall the meaning of an analogous concept. Among these there is usually—not necessarily always, it seems—one or more that stand out as prime analogates for us, i.e., as focal meanings or privileged exemplars closest to us by which we most easily and immediately grasp the meaning experientially, and out from which as from a center we extend it in lessening degrees of clarity. This usually means the properties as experienced and lived in our own selves, whether in body, psyche, or spirit. But it should be clearly understood that these ways of our coming to understand most vividly the common property do not themselves enter into the object meaning of the term when it is predicated analogously, in any of its predications. They are modes of revealing the analogous meaning of the term; they do not constitute its objective meaning itself—otherwise they would restrict it and destroy its analogical spread. Its objective analogical meaning as predicated is deliberately expanded, enlarged, made more vague and indeterminate than these modes of discovery, so that it will be able to transcend them in scope of application. Thus at the same time that we call up these privileged modes in order to evoke the meaning of the concept for ourselves, we understand (at least implicitly, but in a way that effectively controls our use of the term) that the meaning of the analogous term is being left open for further application, that it is not tied down to these modes of discovery. Thus if we were asked, in the example of speaking of hypothetical higher forms of “intelligence” that might communicate with us from outer space, what we mean by “intelligence,” we would say something like this: “You know, the kind of thing we do, being self-conscious, compre-hending the natures and properties of things, making signs or communicating in some way, in a word, understanding, but probably in quite different ways from ours.” We do not confuse the modes of under-standing with the reality understood, or signified.

We could add another aspect (4) which would cor-respond exactly to St. Thomas’ modus significandi, or modes of signifying the res significata. These are often misunderstood as signifying aspect (2), the actual modes of concrete realization of the common property in particular cases, as Professor Nielsen seems to understand them. This is quite incorrect. They are also sometimes extended to coincide with our (3), man’s modes of understanding the res significata. There is no great harm in deliberately using modus significandi with this meaning, and one does need some appropriate term to express these. But it is still not what the expression itself means as Aquinas uses it. It refers only to our human modes of expressing the res significata, i.e., conceptual-linguistic modes. It was originally intended to take care of the obvious difference between the way God’s perfections are found in him and our way of expressing the perfections of God through multiple verbal predicates, each distinct from the other, which are predicated of a subject as though they were accidents inhering in a distinct substance: “God is wise, and loving, and powerful.” This is the way they are found in us, where wisdom can come and go and where a man can be wise but not powerful or vice versa. But what they signify as found in God himself is that God is identically all the positive perfections signified by these terms but united together in a single simple plenitude of perfection. Similarly we speak of God, who is beyond time, through verbal forms with tenses. Yet St. Thomas is quite clear that, although our modes of expressing these attributes bear the mark of their origin in our experience, these modes are not what is expressed and predicated by the concept itself, in any of its predications.6 To say that John is wise and powerful does not mean, though it may indeed be understood to be also true, that wisdom in John is an accidental attribute really distinct from his power and his own essence. It is simply stating that it is true that he is wise and it is true that he is powerful, without stating how these are related. Hence our modes of expression do not corrupt with anthropomorphism our predications about God, or about anything, for that matter. This is as far as St. Thomas’s modes of expressing take us, though he also speaks of the “modes in which a perfection is found” or realized in its subject, which are not quite the same thing, but correspond rather to our modes of realization in (2) above. Where do Copleston’s “objective meaning” and “subjective meaning” fit in here?7 It is not entirely clear to me from his text how they do, and it is no wonder to me that Professor Nielsen had serious—and to my mind quite justified—difficulties with his explanation. For Copleston, the “objective meaning” means “the objective reality itself referred to by the term in question,” which in his example, “God is intelligent,” he maintains is “the divine intelligence itself,” as it is in itself. The “subjective meaning” is “the meaning-content in my own mind . . . primarily determined for me by own experience . . . of human intelligence.” But here it seems that “intelligence” means in this predication “divine intelligence” and yet the only meaning-content in my mind in all predications is “human intelligence.” This opens up a yawning gap between the two which Prof. Nielsen has very astutely seen, and it is not at all clear from this text alone just how one crosses the gap. What Copleston fails to explain is that what he calls the “subjective meaning” is not really the meaning-content in my mind at all which I mean to signify by the analogous concept. It is my way of discovering the meaning, but not the purified more indeterminate analogous meaning itself. He needs another intermediate term in his discussion to indicate this. He comes close to it, in fact, when he adds at the end of his text, not quoted by Nielsen, “But seeing that human intelligence as such cannot be predicated of God, I attempt to purify the ‘subjective meaning’ . . . . And in so doing we are caught inextricably in that interplay of affirmation and negation of which I have spoken.” It is this “purified meaning,” purified by being made more indeterminate and open, that is the one actually predicated of God, which is not Copleston’s objective meaning either, since that is already determined to fit God only. He does not make this clear enough in his text. (I fear there is some confusion too in Fr. Copleston’s text between meaning and reference, when he speaks of the meaning as “the reality referred to.”) Thus it should be clear that I dissociate myself from Fr. Copleston’s explanation and consider it an inaccurate rendering of St. Thomas’s teaching, or at least an easily misleading one. Professor Nielsen has good reasons for finding it unsatisfactory. There is in fact no gap between the meaning of “intelligence “as predicated of God and its meaning as predicated of man. But there is a gap between the modes of realization which I understand this attribute will take on in the concrete in each case, as well as between my mode of coming to understand this meaning and the mode I affirm in God.

III. Application to GodLet us now take brief stock of what we have accomplished. We have tried to explain what the structure of analogous predication is in general, how it works, and what it means to extend the range of an analogous concept beyond its ordinary range in our experience. But the actual extension of our anal-ogous language to some new entity, such as God, that is beyond the range of our experience requires three further steps: (1) we must have good grounds for affirming that there actually is (or at least might be) such a new candidate for the application of our language; (2) we must have good grounds for affirming that this new candidate is actually objec-tively similar in some way or ways to the presently known beings in our experience—in other words, that there are good grounds for applying our concepts and language at all; (3) once we are in possession of these grounds we must then proceed to figure out just which of the attributes in our store of knowledge are apt to be extended meaningfully and legitimately to such an entity. But the first two suppositions cannot be provided by a theory of analogy itself. They must come from outside, to build a bridge across which our analogical language can walk. It is especially the lack of any awareness of the second point above, the establishment of a bond of similarity between God and creatures, that renders Professor Nielsen’s exposition of Thomistic analogy so crip-plingly incomplete. Let us now turn to each of these three points. The first two will be handled together under Section 1.

1. Causality as the Bond of Similarity between God and World

The first step is establishing the existence of God. This is done through a causal argument, which postulates that, under pain of our world of experience falling into unintelligibility, there must exist, as experience’s ultimate condition of intelligibility, or adequate sufficient reason, one ultimate Source of all being, whose only intelligible mode of being must be infinite perfection—for otherwise it could not be the ultimate condition of intelligibility. I would not carry on this argument through the Five Ways of St. Thomas, since they are too incomplete by them-selves and defective in structure to do the job for us today. I would use rather the simpler and more basic metaphysical resources of St. Thomas, not drawn on clearly enough in the Five Ways, to show that no being that begins to exist, or is finite in perfection, or composed in its radical being, or member of a system of dynamically interrelated elements—to sum it up most simply, no finite being or group of finite beings—can supply the sufficient reason or ground of its own existence, and that such an ultimate condition of intelligibility is not reached until we posit an infinite being, a being infinite in perfection.

It is not my purpose to work out this argument here, since it would take another whole article, and our main aim here is explaining the function of analogy within such a framework. Let us therefore suppose that this step has been carried out successfully. If it cannot be, there is no point in discussing Thomistic analogy any further as applied to God. But as soon as we have established the argument, without paying any explicit attention to analogy in the process, we discover that a strange thing has happened. Analogy is already being used in the very formulation of the conclusion: there is an ultimate Source or condition of intelligibility for the existence of. . . , or cause. (This by the way is all we mean by “cause” here in its widest metaphysical sense: that which fulfills a need for intelligibility, which answers the question, “What is effectively responsible for the existence of this datum x, which has turned out to be non-self-explanatory?”—not some meaning drawn from the sciences.)8 For to be intelligible to us, these terms themselves must all be analogous when applied to a being outside our experience.

Does this mean that a vicious circle is here in-volved, that analogy presupposes causality and cau-sality itself presupposes analogy? This is an ex-cellent and crucial question, which Professor Nielsen himself has certainly seen, when he speaks of a circle where one religious statement backs up another. There is indeed a circle of mutual involvement, but it is not a vicious circle; it is a vital one. For it is the very thrust of the mind’s search for intelligibility, reaching out into the unknown to postulate a suffi-cient reason somewhere in being, that both sets up a new beachhead in being for our knowledge to explore further and at the same time carries with it its own enveloping field of analogy. Immanent in the entire innate drive of the mind toward intelligibility is an unrestricted commitment to intelligibility, wherever it may lead, and simultaneously to its objective correlate, being itself, as the source of all answers to this quest. To this range of intelligibility and its correlate being it is impossible to set any limits, since the mind, as soon as it becomes aware of these limits as limits, immediately transcends them by this very awareness. Our own inner experience of this quest for intelligibility that defines the very life of the mind reveals to us that both the quest itself and the answers to it are infinitely Protean, taking on endlessly different forms and modes. In a word, we experience the field of intelligibility, enveloping our own minds and reaching out beyond into its correlate, being, as intrinsically analogical, open-ended but somehow all bound together in some vague unspecifiable unity. The first and all-embracing analogous field which we discover—not by constructing it deliberately but by waking up within it, so to speak—is the correlation intelligibility-being.

Hence it is that when, as in the case of the affir-mation of God, the mind is convinced—for what it believes are good reasons—that it can save the intelligibility of the world of our experience only by positing or postulating as existent outside this world (i.e., transcending its limitations) an ultimate in-finitely perfect source of all being, it necessarily en-velops this term that it posits with its own pre-exis-tent and potentially all-embracing field of analogy, at once positing it as a real condition of intelligibility and as necessarily analogous in the same movement of thought. This initial analogy is extremely vague, not yet extending beyond the immediate correlates of the intelligibility-being field itself, together with the index of location within this field at the supreme apex of perfection, whatever that may be. For all the terms used to describe God in this initial stage, “ultimate condition of intelligibility for the existence of the world = cause,” are nothing but reaffirmations of the general principle of the intelligibility of all being in principle, tailored to the particular situation where the beings we start with do not contain their own sufficient ground of intelligibility within themselves, hence force us to look beyond them.9

Thus the very initial positing of God as cause of the world situates him within the primary a priori (a dynamic and existential, not a logical, a priori) analogous field of both intelligibility and being—of being precisely because this is demanded by intelli-gibility. From the very beginning of our intellectual life there is a necessary mutual co-involvement of in-telligibility, being, and analogy. This very vague ini-tial analogous beachhead of knowledge about God is now ready to be expanded by further judicious search for more determinate valid analogies.

It is at this point that a second crucial corollary of the causal bond comes into play, one that is too often neglected in expositions of analogy, and of which there is likewise no hint in Professor Nielsen’s discussion. This is the principle, handed down to St. Thomas by both the Neoplatonic and the Aristotelian traditions, that every effect must in some way resemble its cause. In a word, every causal bond sets up at the same time a bond of intrinsic similarity in being. In the Platonic-Neoplatonic tradition this took the form of the principle that every higher cause communicated something of its own perfection to its effect beneath it, which participated in the latter as much as its own limited nature allowed. In the Aristotelian tradition it took the form of the principle that no being can cause any perfection in another unless it already possesses in act (in some equivalent way) this same perfection. These two strands were joined together in a single synthesis of causal participation by St. Thomas and other medieval thinkers; and the same general principle of causal similitude has been accepted by most realistic metaphysicians ever since, in one form or another.

The philosophical reason why every effect must in some way resemble its cause, at least analogously, is this: since all the positive perfection of the effect, as effect, derives precisely from its cause(s), the latter cannot give what it does not have; the effect must in some way participate or share in the per-fection of the cause that is its source. If the cause does not possess in an equal, or some higher equi-valent manner, the perfection it communicates to its effects, then the perfection of the latter would have to come from nowhere, have no relation to its cause. Where there is no bond of similarity whatever bet-ween an effect and its cause, there can be no bond of causality either. The similarity in question, however, could be of two main kinds. If both cause and effect were of the same species the similarity would be on the same level and kind, that is, univocal. If the cause were a higher level of being than the effect, then the similarity could not be strictly univocal but would have to be at least analogous. In this perspective, the very fact of establishing a causal link between a lower effect and a higher cause at once ipso facto generates an analogous similarity, a spectrum of objective similarity extending from the known effect at least as far as the cause, whether the latter is directly known or only postulated as a necessary condition of intelligibility for an already known effect. Whether both terms of the relation are known or only one, every effect has to be similar in some way to its cause, or it could not be a real effect, and the same holds for the cause. As St. Thomas sums it up:

Effects which fall short of their causes do not agree with them [i.e., are not exactly like them] in name and nature. Yet some likeness must be found between them, since it belongs to the nature of action that an agent produce its like, since each thing acts according as it is in act. The form of an effect, therefore, is certainly found in some measure in a tran-scending cause, but according to another mode and another way [i.e., analogously]. For this reason the cause is called an equivocal cause [a term that is “equivocal by design” in Aristotelian terminology is the same as what was later called “analogous”—opposed to “equivocal by chance “]. . . . So God gave all things their perfections and thereby is both like and unlike all of them.10

An effect that does not receive a form speci-fically the same as that through which the agent acts cannot receive according to a univocal predication the name arising from that form. . . . Now the forms of the things God has made do not measure up to a specific likeness of that divine power; for the things which God has made receive in a divided and particular limited way that which in Him is found in a simple and universal unlimited way. It is evident, then, that nothing can be said univocally of God and other things. . . . For all attributes are predicated of God essentially. . . . But in other beings these predications are made by participation.11

It is because of this metaphysical context of causality and causal participation undergirding the Thomistic theory of analogy that the most recent and authoritative—in the sense of being almost univer-sally accepted among Thomists— commentaries on St. Thomas’s theory of analogy now all agree that despite his many changes in terminology he fairly early drops the structure of proper proportionality, taken by itself alone, for a richer structure involving both immanent proportionality among the analogates of a term and a reference to the causal source from which the analogous perfection in question is com-municated to all the participating analogates. This fuller metaphysical-semantic structure of anal-ogy as applied to the relation of God and creatures is most aptly called “the analogy of causal partici-pation.” The previously long accepted “orthodox” explanation of Cajetan in terms purely of proper proportionality without reference to a source is now recognized as inadequate to handle the application of analogy to a being not accessible to our experience, as is the case with God. A purely formal isomorphism of relations can supply no positive content of know-ledge about the term of comparison otherwise un-known to us unless some positive intrinsic bond of si-milarity has already been established between both ends of the comparison. Cajetan presumed this had been done elsewhere, but his omission of this step from his formal and explicit analyses of analogy leaves a very serious gap in his formal theory of analogy when taken by itself, as most non-Thomistic thinkers, if not forewarned, would naturally tend to do. St. Thomas himself appears to have come to re-cognize this, since after his early work De Veritate—the main source for Cajetan’s systematization of all Thomistic texts—he never again uses the formal structure of proper proportionality by itself to express his own thought.

Thus it is not surprising that when non-Thomistic thinkers like Professor Nielsen come to the theory of Thomistic analogy through older traditional expositions in the mode of Cajetan, which omit the context of causal participation as part of the doctrine itself as applied to God (or to any unknown cause), they find the structure of the analogy of proper proportionality by itself quite inadequate to perform the role claimed for it. Their critical insight is quite accurate.12

2. Which Attributes Can Be Applied to God?

Once we have set up this basic framework of causal similitude between all creatures and God, from which it follows that there must be some appropriate analogous predicates that can be extended properly and legitimately to God, the next step consists in determining just which attributes can, in addition to the initial most indeterminate attributes of being and perfection, allow for open-ended extension all the way up the scale of being, even to the mode of infi-nite plenitude, without losing their unity of meaning. This is the search for the “simple or pure perfec-tions,” as St. Thomas calls them, which are purely positive qualitative terms that do not contain as part of their meaning any implication of limit or imper-fection. Once we have located one of these, even though we enter into its meaning in first discovering it or in re-evoking it through the limited and imperfect modes (i.e., our privileged modes of exemplifying it to ourselves) belonging to the things we find in our experience, what we intend or mean directly by the concept, once we have purified or enlarged it for good reasons into an analogous concept, is a flexible, broadly but not totally indeterminate core of purely positive meaning that transcends all its particular possible modes, both those we know and those we do not know.

We can recognize that we have effected this purification when we can meaningfully affirm, as we certainly do, that all the experienced modes of these open-ended perfections, such as unity, knowledge, love, and power, are limited, not yet perfect modes. For to affix the qualification “limited or imperfect” to any attribute is already to imply that our understanding of this attribute transcends all the limiting qualifiers we have just added to it. Any attribute that cannot survive this process of purification, or negation of all imperfection and limitation in its meaning (and of course in its actual mode of realization when applied to an infinite being) without some part of its very meaning being cancelled out, does not possess enough analogical “stretch” to allow its predication of God. The judgment as to when this does or does not happen is of course a delicate one that requires careful critical reflection, along with sensitivity to the existential connotations of the use of the term in a given historical culture.13

Two types of attributes have been sifted out as meeting the above requirements by the reflective traditions of metaphysics, religion, and theology: (1) those attributes whose meaning is so closely linked with the meaning and intelligibility of being itself that no real being is conceivable which could lack them and still remain intelligible, i.e., the so-called absolutely transcendental properties of being, such as unity, activity, goodness and power; and (2) the relatively transcendental properties of being, which are so purely positive in meaning and so demanding of our unqualified value-approval that, even though they are not co-extensive with all being, any being higher than the level at which they first appear must be judged to possess them—hence a fortiori the highest being—under pain of being less perfect than the beings we already know, particularly ourselves; such are knowledge (particularly intellectual knowledge), love, joy, freedom, and personality, at least as understood in western cultures.

a) The Absolutely Transcendental Properties

Once established that God exists as supreme infinitely perfect source of all being, it follows that every attribute that can be shown to be necessarily attached to, or flow from, the very intelligibility of the primary attribute of being itself must necessarily be possessed in principle, without any further argument, by this supreme Being, under pain of its not being at all, let alone not being the supreme instance. Thus it is inconceivable that there should exist any being that is not in its own proportionate way one, its parts, if any, cohering into one and not dispersed into unrelated multiplicity. Hence God must be supremely one. Such all-pervasive properties of being are few, but charged with value significance: e.g., unity, intelligibility, activity, power, goodness (in the broadest ontological sense as having some perfection in itself and being good for something, if only itself), and probably beauty too.

Since these properties are so general and vague or indeterminate in their content—deliberately so to allow for their completely open-ended spectrum of application—we derive from this inference no precise idea or representation at all as to what this mode of unity, etc., will be like in itself. But we do definitely know this much: that this positive qualitative attribute or perfection (in St. Thomas’s general metaphysical sense of the term as any positive quality) is really present in God and in the supreme degree possible. Such knowledge, though vague, is richly value-laden and is therefore a guide for value assessment and for value responses of reverence, esteem, etc. I am puzzled as to why Professor Nielsen would consider such value-laden and value-guiding concepts simply empty and hence apparently able to serve no cognitive purpose at all.

b) The Relatively Transcendental Properties

There is a second genre of transcendental attributes of being that are richer in content and of more immediate interest and relevance in speaking about God. These are terms that express positive qualitative attributes having a floor (or lower limit) but no ceiling (or upper limit), and hence are understood to be properties belonging necessarily to any and all beings above a certain level of perfection. Their range is transcendental indefinitely upward but not downward. Such are knowledge (consciousness, especially self-consciousness and intellectual knowledge), love, lovableness, joy (bliss, happiness, i.e., the conscious enjoyment of good possessed), and similar derivative properties of personality in the widest purely positive sense (not the restrictive sense it has in many oriental traditions). All such attributes appear to us as purely and totally positive values in themselves, not matter how imperfectly we happen to possess them here and now. As such, they demand our unqualified approval as uncon-ditionally better to have than not to have. Hence we cannot affirm that any being that exists higher than ourselves, a fortiori the supremely perfect being that God must be, does not have these perfections in its own appropriate mode. To conceive of some higher being as, for example, lacking self-consciousness in some appropriate way, i.e., being simply blacked out in unconsciousness, would be for us necessarily to conceive this being as lower in perfection than ourselves.

Nor is there any escape in the well-known ploy that this might merely mean inconceivable for us but in reality might actually be the case for all we know. The reason is that to affirm that some state of affairs might really be the case is to declare it in some way conceivable, at least with nothing militating against its possibility. This we simply cannot do with such purely positive perfection-concepts.

What happens in our use of these concepts, as soon as we know or suspect for good reasons that there exists some being higher than ourselves, is that, even though our discovery of their meaning has been from our experience of them in limited degree, we immediately detach them from restricting links with our own level, make them more purified and indeterminate in content, and project them upward along an open-ended ascending scale of value appreciation. This is not a logical but an existential move, hooking up the inner understanding of the conceptual tools we use with the radical open-ended dynamism of the intellect itself. One way we can experience this power of projection of perfections or value attributes beyond our own level is by experi-encing reflectively our own poignant awareness of the limitations and imperfection of these attributes as we possess them now, even though we have not yet experienced the existence of higher beings. We all experience keenly the constricting dissatisfaction and restlessness we feel over the slowness, the fuzzy, piecemeal character of our knowing and our intense longing, the further we advance in wisdom, for an ideal mode of knowledge beyond our present reach. The very fact that we can judge our present achievement as limited, imperfect, implies that we have reached beyond it by the implicit dynamism of our minds and wills. To know a limit as limit is already in principle to have reached beyond it in dynamic intention, though not yet in conceptual representation. This point has for long been abun-dantly stressed by the whole Transcendental Thomist school, not to mention Hegel and others, who bring out that the radical dynamism of the spirit inde-finitely transcends all finite determinate conceptual expressions or temporary stopping places.

The knowledge given by such projective or pointing concepts, expressing analogous attributes open-ended at the top, is again very vague and indeterminate, but yet charged with far richer determination and value content than the more universal transcendental attributes applying to all being, high or low. By grafting the affirmation of these attributes, as necessarily present in their appropriate proportionate mode in God, on to the lived inner dynamism of our spirits longing for ever fuller consciousness, knowledge, love (loving and being loved), joy, etc., these open-ended concepts, affirmed in the highest degree possible of God, can serve as very richly charged value-assessment guides for our value-responses of adoration, rever-ence, love, longing for union, etc. But note here again that the problem of the extension of analogous concepts beyond the range of our experience cannot be solved by logical or conceptual analysis alone, but only by inserting these concepts into the context of their actual living use within the unlimitedly open-ended, supra-conceptual dynamism of the human spirit (intellect and will), existentially longing for a fullness of realization beyond the reach of all determinate conceptual grasp or representation. Thomistic analogy makes full sense only within such a total notion of the life of the spirit as knowing-loving dynamism. The knowledge given by these analogous concepts applied to God, therefore, though extremely indeterminate, is by no means empty. It is filled in by a powerful cognitive-affective dyna-mism involving the whole human psyche and spirit, which starts from the highest point we can reach in our own knowing, loving, joy, etc., from the best in us, and then proceeds to project upwards along the line of progressive ascent from lower levels towards an apex hidden from our vision at the line’s end. We give significant meaning to this invisible apex precisely by situating it as apex of a line of unmistakable direction upward. This delivers to us, through the mediation (not representation) of the open-ended analogous concept, an obscure, vector-like, indirect, non-conceptual, but recognizably posi-tive knowledge-through-love, through the very up-ward movement of the dynamic longing of the spirit towards its own intuitively felt connatural good—a knowledge “through the heart,” as Pascal puts it, or through “connatural inclination,” as St. Thomas would have it.14 Such an affective knowledge-through-connatural-inclination is a thoroughly human kind of knowing, quite within the range of our own deeper levels of experience, as all lovers and artists (not to mention religious people) know. Yet it is a mode of knowing that has hitherto been much neg-lected in our contemporary logically and scientifically oriented epistemology.

Conclusion

It is time to conclude this already too lengthy re-sponse. To sum up, analogous knowledge of God, as understood in its whole supporting metaphysical con-text of (1) the dynamism of the human spirit, tran-scending by its intentional thrust all its own limited conceptual products along the way, and (2) the structure of causal participation or causal similitude between God and creatures, delivers a knowledge that is intrinsically and deliberately vague and indeterminate, but at the same time richly positive in content; for such concepts serve as positive sign-posts, pointing vector-like along an ascending spec-trum of ever higher and more fully realized perfec-tion, and can thus fulfill their main role as guides for significant value responses, both contemplative and practical. Such knowledge, with the analogous terms expressing it, is, and by the nature of the case is supposed to be, a chiaroscuro of light and shadow, of revelation and concealment (as Heidegger would say), that alone is appropriate to the luminous Mystery which is its ultimately object—a Mystery which we at the same time judge that we must reasonably affirm, yet whose precise mode of being remains always beyond the reach of our determinate representational images and concepts, but not beyond the dynamic thrust of our spirit which can express this intentional reach only through the open-ended flexible concepts and language we call analogous. Such concepts cannot be considered “empty “save in an inhumanly narrow epistemology.

Notes

1 For a summary of these developments, see David Burrell, Analogy and Philosophical Language (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), Chap. 6 on Aquinas, and G. Klubertanz, St. Thomas Aquinas on Analogy (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1960).

2 Although I had come to this conclusion some time ago myself, I am deeply indebted to Fr. Burrell for his fine elucidation of this point, one of the main ones in his fine book cited in n. 1.

3 Cf., on Scotus, Burrell, op. cit., Chap. 5 and 7; C. Shircel, Univocity of the Concept of Being according to Duns Scotus (Washington: Catholic University of America, 1942); on Ockham, Burrell, op. cit., Chap. 7; M. Menges, The Concept of the Univocity of Being regarding the Predication of God and Creatures according to William Ockham (St. Bonaventure, N. Y.: Franciscan Institute, 1958).

4 E. Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas (New York: Random House, 1956), pp. 105-107.

5 St. Thomas himself is quite clear about this. Cf. his sensitive basic treatment in Summa Theol., I, quest. 13 entire, esp. art. 3: “Some words that signify what has come forth from God to creatures do so in such a way that part of the meaning of the word is the imperfect way in which the creature shares in the divine perfection. Thus it is part of the meaning of “rock” that it has its being in a purely material way. Such words can be used of God only metaphorically. There are other words, however, that simply mean certain perfections without any indication of how these perfections are possessed—words, for exam-ple, like ‘being,’ ‘good,’ ‘living,’ and so on. These words can be used literally of God” (the translation is the new English one edited by Thomas Gilby, Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, Vol. I, Garden City, Doubleday Image Book, 1969).

6 See his text in note 5.

7 The main part of the text Professor Nielsen is quoting (Contemporary Philosophy, Westminster, Md.: Newman Press, 1956, p. 96) runs as follows: “By ‘objective meaning’ I understand that which is actually referred to by the term in question (that is, the objective reality referred to), and by ‘subjective meaning’ I understand the meaning-content which the term has or can have for the human mind. . . i.e., my understanding or conception of what is referred to. . . . If this distinction is applied to the proposition ‘God is intelligent,’ the ‘objective meaning’ of the term ‘intelligence’ is the divine intellect or intellect itself. . . . And of this I can certainly give no positive account. . . . The ‘subjective meaning’ is the meaning-content in my own mind. Of necessity this is primarily determined for me by my own experience, that is, by my experience of human intelligence. But seeing that human intelligence as such cannot be predicated of God, I attempt to purify the ‘subjective meaning’ . . . . And in doing so we are caught inextricably in that interplay of affirmation and negation of which I have spoken.”

8 For this whole question of the meaning of “cause” in the context of the mind’s quest for intelligibility and its necessarily analogous character as a correlate of the enquiring mind at work, see my own fuller development in “How the Philosopher Gives Meaning to Language about God,” in The Idea of God, ed. by E. Madden, R. Handy, M. Farber (Springfield, III: Charles Thomas, 1968), pp. 1-28; and “Analytic Philosophy and Language about God,” in Christian Philosophy and Religious Renewal, ed. by G. McLean (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1966), pp. 39-73, esp. pp. 46-51, 61-71.

9 It is very important to make the point here that according to St. Thomas’s metaphysical method—and any sound metaphysical method, it seems to me, which seeks to achieve knowledge of some being beyond our experience—it is a fatal error to accept the demand so habitually made by analytic philosophers and others that one must define what he means by “God” before undertaking to establish His existence. This stand is not an evasion; it is a question of proper method. It is impossible philosophically to give any definition of God that can be shown to make sense before actually discovering Him as an exigency of the quest for intelligibility. The meaning of “God” emerges only in function of the argument that concludes to the need of a being to which we then can appropriately give the name “God” or not, according to our culture and religious tradition. The philosophical meaning of God should be exclusively a function of the way by which He is discovered. Hence a properly philosophical approach to the existence of God should not ask, “Can I prove that God exists?” but rather, “What does the world of my experience demand in order to be intelligible?” Following out this exigency rationally, we “bump into” God, so to speak, as a being all of whose properties are defined exclusively by its needs to fulfill its job of satisfying the exigencies of the quest for intelligibility. Hence any philosophical “proof for the existence of God” has already taken the statement of the question from some non-philosophical source, usually religion.

10 Summa Contra Gentes, Bk. I, chap. 29, n. 2. Cf. also Summa Theol., I, q. 13, a. 5.

11 Ibid., chap. 32, nn. 2 and 7. He goes on to say in chap. 33, n. 2: “For in equivocals by chance there is no order or reference of one to another, but it is entirely accidental that one name is applied to diverse things. . . . But this is not the situation with names said of God and creatures, since we note in the community of such names the order of cause and effect. . . .”

12 It is because of this basic similitude between all creatures and God that the phrase applied so often to God by theologians, philosophers of religion, and spiritual writers, describing His transcendence over creatures, namely, that God is “totally Other,” is really, if taken in unqualified literalness as a metaphysical statement, quite unacceptable as sound philosophy, theology, or spirituality. For if God were literally totally other, with no similitude at all with us, there could be no bond whatsoever between us, no affinity drawing toward union as our true Good, no image of God deep in the soul, etc. He might be totally other in His essence or mode of being, since He is beyond all form, but not totally other in His being itself or the activity properties that flow directly from its fullness of perfection.

13 Cf. for a fuller development my articles cited in note 8.

14 Cf. Summa Theol., I, q. 1, a. 6 ad 3; I-II, 9-45, a. 2. Also J. Maritain, “On Knowledge through Connatural-ity,” Review of Metaphysics, IV (1950-51), 483-94; V. White, “Thomism and Affective Knowledge,” Black-friars, XXV (1944), 321-28; A. Moreno, “The Nature of St. Thomas’ Knowledge per connaturalitatem,” Angel-icum, XLVII (1970), 44-62.