AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

At the fourth meeting of the New York University Institute of Philosophy in 1960, Father Clarke contributed critiques of fellow symposiasts, Paul Ziff, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Paul Tillich. Sidney Hook, who organized the symposium, edited the proceedings for publication in 1961 as Religious Experience and Truth: A Symposium, New York University Press, arranging Clarke’s critiques as three sections of Chapter 28, “On Professors Ziff, Niebuhr, and Tillich” (224-230). The following remarks on a paper by Reinhold Niebuhr appear on pages 226-227.

Anthony Flood

May 10, 2010

On Professor Niebuhr’s Paper, “On the Nature of Faith”

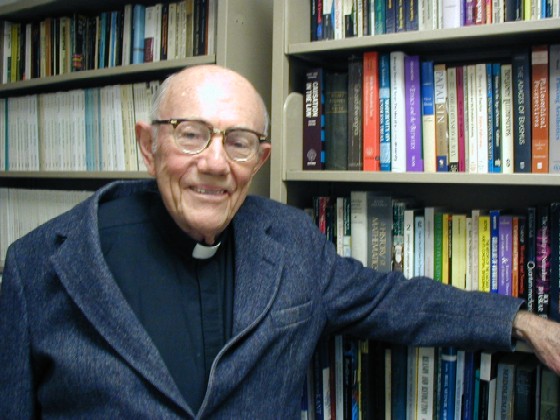

W. Norris Clarke, S.J.

Professor Niebuhr’s sole aim in his paper has been to do the preliminary work of analyzing the whole spectrum of phenomena which we call “faith” in our language. He has done what seems to me, for the most part, quite a successful job. In thus trying to separate clearly all the “pure colors” on this spectrum, however, I believe he has in one case separated what in reality are always or for the most part joined together. His major distinction is between kinds of faith having to do primarily with knowledge and kinds having to do primarily with interpersonal trust, confidence, and the like. All well and good in itself and in most of its applications. But I do not think that species I(d), “personal know-ledge,” under the cognitive genus, can be separated from or found without the interpersonal “trust” kind of faith characteristic of his second main genus. He identifies the first with the kind of knowledge Newman called “personal knowledge,” and he de-scribes it as follows: “it may be a kind of totality of the apprehending self that apprehends as a psycho-somatic-rational-spiritual whole. . . . For J. H. New-man, religious assent is a function of the whole per-son confronting a totality.”

But it is precisely because such an attitude involves the whole person as an existential totality in action that it must include the basic will attitudes of interpersonal trust, confidence, commitment, etc. I believe this is almost certainly how Newman himself understood this type of attitude faith. Historically, it is quite true that the Hebrews seemed to have focused more explicitly on the trust kind of faith and the Greeks on the cognitive. But it is precisely part of the genius of Christianity that it fused the two into a single and henceforth indissoluble spiritual attitude in its own new and much richer conception of faith as total commitment, at once intellectual and voluntary, of the whole person to God. Again, within Chris-tianity, the Protestant tradition has tended to stress more the trust element and the Catholic the cognitive (in the latter case because its theology has analyzed the original rich whole of Biblical “faith” into the distinct, but not separated, theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity). But it still remains that, if we are not to denature or impoverish the reality we are trying to analyze in the concrete, any act of what Niebuhr, following Newman, calls “personal know-ledge,” involving the “totality of the apprehending self,” “the whole person confronting a totality,” must necessarily include the whole will dimension of trust, commitment, etc. Therefore, I would here unite what Professor Niebuhr has, it seems to me, a little too sharply distinguished.