AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From The Thomist 61 (1997), 617-24. “[R]eceptivity in its very meaning is a pure perfection . . . .” The original title was simply “Reply to Steven Long.”

Anthony Flood

May 11, 2010

The Compatibility of Receptivity and Pure Act: Reply to Steven Long

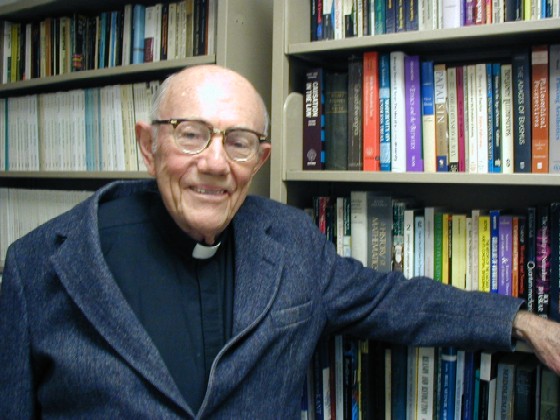

W. Norris Clarke, S.J.

In an article entitled “Personal Receptivity and Act,”1 Dr. Steven Long has criticized Prof. Kenneth Schmitz and myself for violating one of the fundamental metaphysical principles of St. Thomas: the universal applicability of the act-potency composition to explain all communication of perfec-tion between beings. The main thrust of his critique (some twenty pages) is directed against Professor Schmitz; only three or four pages are directed at my position. I will not concern myself with the critique of Professor Schmitz but only with what concerns my own position.2 I do not find it helpful to answer all criticisms, but in the present case I think it is well worth doing because there are wider and more important issues at stake “behind the scenes,” namely, the intelligibility of a distinctively Christian philosophy.

The particular position of mine that is being attacked is my suggestion that the notion of receiving (“receptivity” in the abstract)—which is ordinarily associated in our world with potency, limitation, and imperfection—should be reevaluated and taken as signifying in itself a positive ontological perfection, which is always realized indeed in the world of creatures as mixed with potency and limitation, but in itself signifies a purely positive perfection, with all the implications this connotes.3

My defense of this position is quite explicitly an exercise in “Christian philosophy,” that is, using the Christian revelation of the Trinity (one God in three Persons) as a principle of illumination (not rigorous, purely philosophical argument) to shed new light on the deeper meaning of both person and being, help-ing us to notice more positive aspects of both even in our own world that may have escaped our attention so far. This kind of specifically Christian philoso-phizing has been practiced very fruitfully in recent years in this country by Christian thinkers, including some of the Editors of The Thomist (e.g., taking the Trinity as model of human social relations).

My own contribution to this creative and exciting project is its application to receptivity, leading to a reevaluation of receptivity as a positive ontological perfection. The source of this reevaluation is reflec-tion on the inner interpersonal life of the Trinity, where we find that giving and receiving are integral and inseparable aspects of the very fullness of per-fection in the loving communion of persons within the unity of one divine nature, that actually constitutes the very infinite fullness of perfection of being itself in its highest realization. For just as the Father’s whole personality as Father consists in his communicating, giving, the entire divine nature that is his own to the Son, his eternal Word, so reciprocally the Son’s whole personality as Son consists in receiving, eternally and fully, with loving gratitude, this identical divine nature from his Father. The Son, as distinct from the Father, is subsistent Receiver, so to speak. Since this communication is always going on, yet always full and complete, there is absolutely no potency, li-mitation, or imperfection here. Both are aspects of pure actuality, of Pure Act—in the Thomistic, though not the Aristotelian sense of the term. And according to Christian dogma, explicitly defined by the Council of Chalcedon in 451, both aspects, giving and re-ceiving, the status of the Father as Giver and that of the Son as Receiver, are of absolutely equal value and perfection. Any denial of this would be heresy. All this follows from the basic definition (1) that the three Persons are really distinct as persons; (2) that this distinction is a distinction only of relations of ori-gin, of origination, that is, of giving and receiving the identical divine nature in all its fullness. As Jesus said (and this is the scriptural source of the doctrine), “All that I have I have received from my Father” (or, “I have from my Father”); “All that the Father has he has given me.”

There is real communication here; and where there is real communication, there is real giving and receiving: giving and receiving are complementary antonyms—there is no giving without receiving. To deny this is to deny the real relations of origin that constitute the Persons as distinct, and so the real distinction of the Persons collapses too. It is clearly unorthodox to consider all this as merely meta-phorical. Yet this communication between the Per-sons is so perfect that it does not break up into two separate beings, which would require some limitation on the part of the receiver in order that the two beings could be distinguished, but folds together into the unity of one being. That is why in Christian theology it is not called a causal communication (which implies the real distinction of cause and effect as two different beings), but rather a “procession.” It is not a communication between beings, but between persons within one being.

What follows from this is the truly illuminating conclusion that receiving, receptivity, does not, cannot of itself signify limitation and imperfection in its very meaning, but rather is in itself a pure positive ontological perfection, a necessary aspect of the very fullness of being itself as Persons-in-commu-nion, as opened up for us in the revelation of God as Trinity. The term must be, of course, analogous as applied to both creatures and God. But it cannot be simply equivocal. One of my critics has said, “Receptivity and Pure Act are incompatible.” But then Jesus’ own words lose all meaningful content; they confer no new information to us at all, but merely a word play—which is quite unacceptable to a Christian. Moreover, if “receiving” becomes equi-vocal, emptied of meaning, so too does “giving.” Therefore the very fullness of being itself, Pure Act, which is now identical with Persons-in-communion, contains giving-receiving as inseparable aspects of its very perfection of being, of equal value and impor-tance. Not at all an Aristotelian conception of Pure Act, but certainly a Thomistic one, for Thomas’s own metaphysics, as illumined by his theology.

Let us look briefly at the rich implications of the above for shedding new light on our own world of interpersonal relations among humans. Since both giving and receiving are integral components of the full perfection of being, as found in God, our Creator, then it must be that we, as images—however imperfect—must somehow imitate both aspects of this divine perfection as best we can in our own personal lives. For us, too, the highest human perfection must be persons-in-communion, and both giving and receiving must have their place there as part of the perfection of our lives as persons. The notion of the self-sufficient self, who gives indeed magnanimously of his own riches but who would feel himself somehow diminished if he had to receive from another, make himself “dependent” on another, is a dangerously illusory and misleading myth, not only from a Christian point of view but from any adequate phenomenology of interpersonal relations.

In fact, as we observe and reflect on the success or failure of human interpersonal relations, especially those of love of friendship, it becomes clear that the higher we go, the more receiving, as well as giving, becomes an integral part of the very perfection—not imperfection—of our love relations. The balance becomes more perfect and equal as we approach slowly, though without ever being able to reach, the perfectly balanced status in God. Potency always remains to some degree on our level as creatures—because of motion and progression, because we can never fully express or communicate our whole being to another human person as the Persons in God can. Still, the point is that the potency in us, at the personal conscious level, as we progress in personal love relations, becomes more and more interwoven with positive perfection, that is, with active, welcoming, grateful acceptance, which are modes of actuality, not simply passive potency. For notice how at the level of a conscious love relation the receiving potency itself must be fully conscious, conscious precisely of receiving from the other. And the process of conscious giving and receiving is not completed until it is received consciously, gratefully accepted. Receiving here is not an unconscious pro-cess, upon which follows a conscious grateful accep-tance. The receiving itself contains as an integral part the grateful acceptance. Therefore, in a con-scious potency actuality and act are mixed in with the very potency itself. It is not pure passivity, pure passive potency, but a potency that is mixed, partly passive, partly active. The active part grows and grows toward matching the giving part, as far as it can. The abstract consideration of act and potency as pure giving on one side and pure passivity on the other is much too crude a lens to do justice to the richness of interpersonal relations, either on the divine or on the human level.

Now we come to the criticism of Steven Long, who, by the way, I respect from elsewhere as both a good young Thomistic scholar and a committed Christian philosopher. He will have none of this re-evaluation of receptivity. He insists on defining re-ceptivity as intrinsically including the notes of po-tency, limitation, imperfection. He defines it as the causal communication of perfection from one being to another being:

One must first settle what the term “recep-tivity” designates. If it indicates the posses-sion of a perfection by virtue of another and not by virtue of oneself, then the subject re-ceiving does not originate the perfection. . . . indicating that it does not, simply speaking and through itself, possess the perfection.

If the receiving subject does not originate the perfection . . . [it] is not simply self-actualizing. From this very datum it becomes manifest that a received pure perfection cannot be received in its totality.

The totality of a pure perfection excludes po-tency, while the potency for some perfection—to be actualized through another rather than simply through itself—is necessary for re-ceptivity. Potency is discernible in the sub-ject’s nonpossession of the perfection apart from the causality of another. Naturally speaking, receiving indicates potency.4

Although there is much in this text and in the rest of Long’s discussion that I find acceptable on the strictly creaturely level of interchange between beings, I must also say with regret that I find his reply as a whole seriously inadequate, missing the mark, so to speak, as a critique of my position as I have expounded it. Specifically, he has omitted any mention of the higher dimension of the interpersonal life of the Trinity, opened up to us by Christian revelation, which was my principal source of evidence for throwing new light on what it means to be and to be a person; thus he has missed the point of what I had explicitly intended as an exercise in Christian philosophy. Let me spell out my response briefly.

To begin with, it is obvious, as he says, that “the totality of a pure perfection excludes potency” in a Thomistic metaphysics—and in mine too; it is also obvious that to receive perfection “from the causality of another” implies potency and imperfection. But it is not obvious—nor does he attempt to prove it—that all receiving of perfection by one subject from another implies potency, nor that “a received perfection cannot be received in its totality.” For the latter is precisely what happens in the Trinity, in the communication of the divine nature from the Father to the Son. It is indeed communication between persons, not separate beings, and by “procession,” not efficient causality. Long does not draw these essential distinctions, but makes an unqualified general statement that is clearly false when applied to the Trinity. One must ask what sense then can be made of the revealed and defined doctrine of the Trinity, as indicated above, where both giving and receiving are integral to the interior life of self-communicating love between the three Persons. The scriptural texts themselves are stunningly precise: “All that I have I have received from my Father”; and “All that the Father has he has given to me” (the “All” in the latter text shows that this concerns the eternal divine life of the Son, not his created human nature, to which the Father did not give all that he had).

I see no way that one could question this and still remain a Christian thinker. Long’s argument, in fact, includes no reference to the Trinity, which was the main source of evidence, the central point, of my whole development. His critique is therefore at its heart inadequate. To hold that theology and revela-tion are irrelevant for philosophy is inadmissible for a Christian philosopher. The more common position, that theology must be separated from philosophy so as not to influence it unduly, is a respectable position for a Christian thinker. But even here theology is always taken as a negative norm, in the sense that no statement in philosophy will be allowed that contradicts or renders unintelligible a statement from theology, at least in its formally defined parts. Unfortunately that seems to be exactly what Long has unwittingly—and I am sure unintentionally—done when he says that “a pure perfection cannot be received in its totality.” But it is, by the Son in the Trinity—not from one being to another, but from one Person to another Person! And it is real commu-nication, real giving, and real receiving. How can the antinomy be reconciled?

It may be that Long has fallen into the Aristotelian trap of considering complete self-sufficiency, self-originated perfection, not only in the order of being but of persons too, to be the necessary condition for any authentic fullness of perfection, of Pure Act. Even in Aristotle’s admirable book 9 of the Nico-machean Ethics, on friendship, with its stress on the reciprocity between friends, there occurs this re-vealing sentence, which might indicate that some further refinement of the perfection of the love of friendship may have escaped him: “Further, love is like activity, being loved like passivity; and loving and its concomitants are attributes of those who are the more active” (c. 7 [1168a19]). Not so in the world of the divine Persons, not so without qualification even among human persons, and therefore not so for an adequate Christian philosophy, and not for St. Thomas, who asserts clearly the non-self-origination of the perfection of the Son in the Trinity: “It is of the nature [or meaning: de ratione Filii est] of the Son to be related only to the Father as existing from him [ut existens ab eo]” (De Potentia, q. 10, a. 4).

Finally, Long seems to think that I believe recep-tivity is realized as a pure perfection among crea-tures, including created persons. Not at all; my point is that receptivity in its very meaning is a pure perfection, contains no limitation or imperfection in its very meaning so as to become intrinsically a “li-mited or mixed perfection.” But it is always realized in creatures—as is true of all pure perfections, unity, goodness, truth, etc.—in an imperfect, limited way. That is why receptivity in creatures is not simply re-ceptivity, but limited, imperfect receptivity.

I rest my case here. It may seem that I have been somewhat harsh in my reply to my critic. I am not accustomed to writing in this way. I did so only because I consider it so important today to make it clear how incomplete, even misleading, it can be when a Christian philosopher tries to ignore, or take no account of, the distinctively new and powerful light that Christian revelation, in particular that of the Trinity, sheds on what it means both to be and to be a person. My final word: Is there a authentic and intel-lectually respectable project of distinctive Christian philosophizing? My answer is a resounding “Yes!”

Notes

1 Steven A. Long, “Personal Receptivity and Act: A Thomistic Critique,” The Thomist 61 (1997): 1-31.

2 [Editor’s note: Professor Schmitz has also res-ponded to Dr. Long: Kenneth Schmitz, “Created Re-ceptivity and the Philosophy of the Concrete,” The Thomist 61 (1997): 339-71.]

3 This position is laid out in my book Person and Being (Marquette University Press, 1993), chap. 1, sect. 3, and chap. 3, sect. 5; in my article “Person, Being, and St. Thomas,” Communio 19 (1992): 601-18; as well as in the forty-page discussion of the point, including a strong defense by the Editor against my critics, in Communio 21 (1994): 151-90.

4 Long, “Personal Receptivity and Act,” 27-28.