AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From International Philosophical Quarterly, 30:1, March 1990, 109-111. Review of David Braine, The Reality of Time and the Existence of God: The Project of Proving God’s Existence. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. Pp. 383.

Anthony Flood

July 20, 2011

Review of David Braine, The Reality of Time and the Existence of God: The Project of Proving God’s Existence

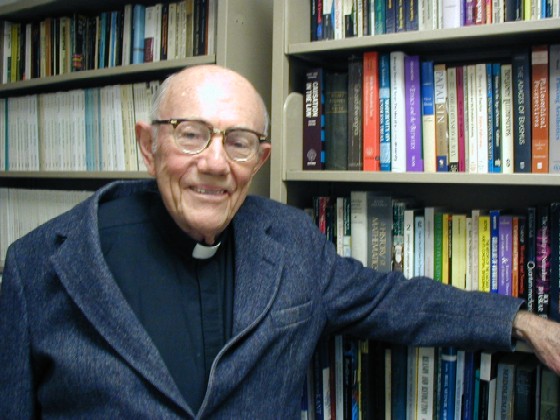

W. Norris Clarke, S.J.

This book is a considerable surprise. Coming from a background of analytic philosophy of language—the author is Gifford Fellow and Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Aberdeen and former student of Gilbert Ryle at Oxford—it ventures out boldly to lay down a robust realist metaphysics of real substances as active agents exercising active causal power in time, and then draws from this a carefully worked out argument to the existence of God as the necessary transtemporal cause of the whole temporal order of agents. Although grateful for his analytic training and drawing upon it heavily, the author seems to have reached his conclusions by his own personal reflections, aided by a profound and remarkably accurate understanding of the basic positions of Thomas Aquinas in metaphysics and natural theology. Although he works out his own technical terminology quite different at first appearance from that of St. Thomas, the dependence and affinity of thought emerges more and more clearly as he goes on. This may be the best way, in fact, to make Aquinas an effective presence in contemporary thought.

But the book is definitely not for amateurs. It works its way to its conclusions by an austere and intricately interlocking pattern of argumentation that requires the closest attention even from a professional philosopher. One of the difficulties is that the main line of argumentation to the existence of God is frequently put on hold while the author works out the basic metaphysical and methodological foundations on which his argument depends at this point. One can see why he feels this is necessary in a contemporary context, especially his own, but it does not make for easy reading. The result is highly rewarding, however, for those who can stay the course.

The author’s first move is to justify reflectively the basic common sense vision of the world as composed of real substances as active agents exercising active causal power on other substances in a real temporal order. He does this briefly but well, showing the inadequacy of the anemic causal theory of the empiricist, David Hume, in which active causal power is reduced to mere regular sequences of events in time, such that given the experience of regular sequence we can predict the consequent from the antecedent according to some law (statistical or otherwise), but without any ontological link of effective action and dependence between the two. This theory of the causal relationship, which would, of course, render it impossible to argue from an experienced effect to a non-experienced cause (such as God), is still widely popular among philosophers, at least in its central refusal to move from something in experience to a cause outside of experience.

He then goes on to assert the reality of time, in the sense that, although the past and the present are given, the future as related to a particular present “now” is radically contingent, that is, it does not yet exist, is not given; and furthermore, there is nothing in the past of a temporal being (one whose existence and activity are continuously spread out across time) that can guarantee or assure its continuance into the not yet given future. From this he builds his central argument to the existence of God as a time-transcending cause which does not have or receive existence but is identical with existence itself. The argument goes as follows: It is characteristic of any temporal being, whose very being and activity are imbedded in continuous temporal unfolding, that it contains nothing within its past or present that can absolutely guarantee its continuance into the not yet existent future. This radical impotence to ensure, to be master of, its own future existence is rooted ultimately in the “compositeness” of every temporal being, i.e., the non-identity between its nature and its actual continuing existence, the “that which” and its “is.” Every such being demands a non-temporal, time-transcending cause that eternally possesses existence as part of its very nature, is “in charge of existence,” so to speak. Such a cause does not compete with temporal causes, but is the necessary precondition for their continued existence as active natures, exercising their active causality across time into the future.

He then goes on to show such a cause must be infinite in perfection, one, and also personal, since personhood is a term inclusive of all perfections, hence not limited, and necessary for a spiritual-natured cause to exercise “intentional causality.” He concludes with a cogent argument that any sound theology must have a metaphysical foundation to give a critical control over the analogical application and interpretation of attributes predicated of God.

It is amazing how close the author is in spirit and doctrinal content to St. Thomas in all this, though not in terminology. But what of the overall cogency of the book’s arguments? I think most of his supporting arguments on points of metaphysics and epistemo-logy, his derivation of the divine attributes, his insistence on the need of metaphysics for sound theology, etc. are well taken indeed and show an extraordinary gift for clear metaphysical thinking in a fresh way that I find most invigorating. As regards his central argument, though, from the impotence of any temporal being to ensure its own continuance in existence and hence its need of a supra-temporal cause, this is a new form, adapted to temporal existence, of the ancient contingency argument, taken over by St. Thomas from Avicenna (Summa contra Gentes, I, Ch. 15, #5), namely, that anything which comes into or passes out of existence is radically contingent, i.e., it can be or not be, and thus demands a cause to determine it to be rather than not be. It seems to me to have great promise and contain a deep truth. But in view of its central importance the author moves far too quickly through it, seeming at times to take it as a matter of almost obvious intuition. It needs more careful unpacking, especially as to the exact relationship between the compositeness of a temporal being and its impotence to ensure its continued existence through time.

As a result of the constant interruption of the main argument to establish its metaphysical and epistemological foundations in elaborate detail, often in different parts of the book, the reader seeks in vain for a single, continuous, uninterrupted development of the argument in full detail, with the exact weight and reasons for each step presented as it arises. This is especially needed for the two key steps, 1) that no temporal being can ensure its own future existence and activity and 2) that in every temporal being there must be a non-identity between its nature and its continuing existence (and why this compositeness requires a cause). What needs more explicit clarification and unpacking is precisely the root of the contingency of a being whose existence is unfolded over time. Is it simply the unfolding over time by itself that indicates the being is not master, or self-sufficient source, of its own existence? But suppose this development is merely in the accidental order, with the substance perduring essentially unchanged? Would this still entail a cause for the existence of the substance itself? Or is the real core of the argument the exigency that any such unfolding of a being through time must be dependent for its development on the cooperation of other beings in the universe over whose being it does not have control? This point is mentioned once, but it is not clear how much weight it is expected to carry. It seems to me it carries a great deal, and may perhaps be the decisive point. But this would make the argument in substance be one from the dependence of temporal beings on a wider order of activity in the universe in which they are inserted, an argument from order in a dynamically developing temporal system. The point of the argument, if this is it, should be made clearer.

It is noteworthy that the author systematically prefers Aristotelian ways of framing St. Thomas’ arguments, wherever possible, revealing a certain allergy, or at least undue caution, it seems to be, toward the Neoplatonically-inspired participation aspect of Aquinas’ metaphysics—now well enough established historically, it would seem to me—an attitude easily understandable in those coming to St. Thomas from an analytical background. Thus he gives less metaphysical density to terms like “finite” and “infinite” than I think Aquinas does, and maintains that he sees no sound argument to the uniqueness of the First Cause from its infinity, whereas in fact this path is central to St. Thomas’ procedure.

He also seems to be too hasty and unsympathetic in brushing aside the Transcendental Thomist approach, which he accuses of overstressing a priori, abstract, universal principles of intelligibility and sufficient reason—which he unfairly criticizes as “univocal”—rather than deriving causal intelligibility more existentially from varied examples, or classes of examples, in experience, which are then only later unified into general analogous principles. I think he describes St. Thomas’ own procedure accurately and with insight, but takes for granted the deep existential drive for intelligibility which underlies for Aquinas the whole search of the mind for causal explanation and which Transcendental Thomism is trying to thematize more explicitly and rigorously.

But the above are secondary controversial points in a book exhibiting both admirable metaphysical depth and insight and skilled adaptation of St. Thomas to contemporary modes of thought and language. This fresh new voice from an author who has promised us also two other major syntheses of epistemology and philosophy of man is most welcome in a field where all too few dare to tread these days.