AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

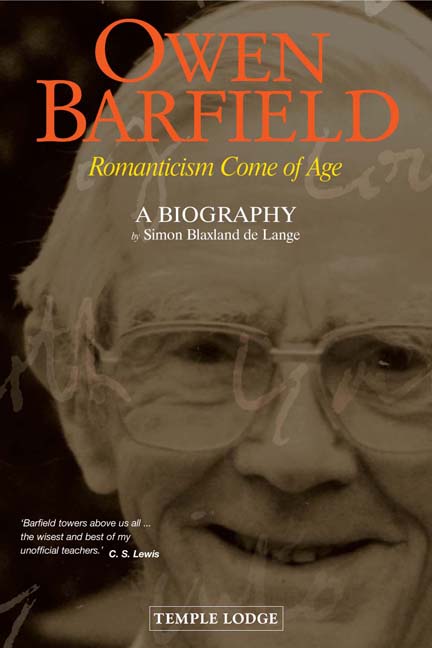

“Barfield towers above us all . . . the wisest and best of my unofficial teachers.”

C. S. Lewis

From Susanne Langer, Feeling and Form, Scribner’s & Sons, 1953, 236-39.

Langer’s own words inspired this excerpt’s title. It was “pure coincidence” to her that Ernst Cassirer and Owen Barfield—fellow “Inkling” to C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Charles Williams—pondered independently “precisely the same problem of non-discursive symbolism.” This “striking parallel” was, however, significant enough to merit emphasis. That Lewis and Langer were intellectually indebted to men who labored in the same vineyards and harvested the same fruit while unknown to each other is a tantalizing fact provocative of further questions.

Other scholars have explored the Cassirer-Barfield parallelism, but Langer was the first to note it over a half-century ago.

Anthony Flood

June 25, 2009

Cassirer and Barfield: A “Striking Parallel”

Susanne K. Langer

Philosophers have been slow to recognize the fact that there are any general laws governing imagination, except insofar as its processes interfere with those of discursive reason. Hobbes, Bacon, Locke, and Hume noted the systematic tendencies of the mind to error: the tendencies to associate ideas by mere contiguity in experience, hypostatize concepts once abstracted and treat them as new concrete entities, attribute power to inert objects or to mere words, and several other vagaries that lead away from science to a state of childish error. But until recently, no one asked why such fantastic errors should occur with monotonous persistence.

As it often happens in the history of thought, the problem presented itself suddenly to a number of people in different fields of scholarship. The outstanding answer to it was given by Ernst Cassirer, in his great work, Die Philosophie der symbolischen Formen. The first of Cassirer’s three volumes concerns language, and uncovers, in that paradigm of symbolic forms, the sources both of logic and of its chief antagonist, the creative imagination. For in language we find two intellectual functions which it performs at all times, by virtue of its very nature: to fix the pre-eminent factors of experience as entities, by giving them names, and to abstract concepts of relationship, by talking about the named entities. The first process is essentially hypostatic; the second, abstractive. As soon as a name has directed us to a center of interest, there is a thing or a being (in primitive thinking these alternatives are not distinguished) about which the rest of the “specious present” arranges itself. But this arranging is itself reflected in language; for the second process, assertion, which formulates the Gestalt of the complex dominated by a named being, is essentially syntactical; and the form which language thus impresses on experience is discursive.

The beings in the world of primitive man were, therefore, creations of his symbolizing mind and of the great instrument, speech, as much as of nature external to him; things, animals, persons, all had this peculiarly ideal character, because abstraction was mingled with fabrication. The naming process, started and guided by emotional excitement, created entities not only for sense perception but for memory, speculation, and dream. This is the source of mythic conception, in which symbolic power is still undistinguished from physical power, and the symbol is fused with what it symbolizes.

The characteristic form, or “logic,” of mythic thinking is the theme of Cassirer’s second volume. It is a logic of multiple meanings instead of general concepts, representative figures instead of classes, reinforcement of ideas (by repetition, variation, and other means) instead of proof. The book is so extensive that to collect here even the most relevant quotations would require too much space; I can only refer the reader to the source.

At the very time when the German philosopher was writing his second volume, an English professor of literature was pondering precisely the same problem of non-discursive symbolism, to which he had been led not by interest in science and the vagaries of unscientific thought, but by the study of poetry. This literary scholar, Owen Barfield, published in 1924 a small but highly significant book entitled Poetic Diction, A Study in Meanings. It does not seem to have made any profound impression on his generation of literary critics. Perhaps its transcendence of the accepted epistemological concepts was too radical to recommend itself without much more deliberate and thorough reorientation than the author gave his readers; perhaps, on the exact contrary, none of these readers realized how radical or how important its implications were. The fact that this purely literary study reveals the same relationships between language and conception, conception and imagination, imagination and myth, myth and poetry, that Cassirer discovered as a result of his reflection on the logic of science.1

The parallel is so striking that it is hard to believe in its pure coincidence, yet such it seems to be. Barfield, like Cassirer, rejects Max Müller’s theory that myth is a “disease of language,” but praises his distinction between “poetic” and “radical” metaphor; then goes on to criticize the basic assumption contained even in the theory of “radical metaphor,” that the carrying over of a word from one sphere of sense to another, or from sensory meanings to non-sensory ones, is really “metaphor” at all.

“The full meanings of words,” he says, “are flashing, iridescent shapes like flames—ever-flickering vestiges of the slowly-evolving consciousness beneath them. To the Locke-Müller-France way of thinking,2 on the contrary, they appear as solid chunks with definite boundaries and limits, to which other chunks may be added as occasion arises.”

He goes on to question the supposed occurrence of a “metaphorical period” in human history, when words of entirely physical meaning were put to metaphorical uses; for, he says,

“these poetic, and apparently metaphorical values were latent in meaning from the beginning. In other words, you may imply, if you choose, with Dr. Blair,3 that the earliest words in use were ‘the names of sensible material objects’ and nothing more—only, in that case, you must suppose the ‘sensible objects’ themselves to have been something more; you must suppose that they were not, as they appear at present, isolated, or detached, from thinking and feeling. Afterwards, in the development of language and thought, these single meanings split up into contrasted pairs—the abstract and the concrete, particular and general, objective and subjective. And the poesy felt by us to reside in ancient language consists just in this, that, out of our later, analytic, ‘subjective’ consciousness, a consciousness which has been brought about along with, and partly because of, this splitting up of meaning, we are led back to experience the original unity.”4

“In the whole development of consciousness . . . we can trace the operation of two opposing principles, or forces. Firstly [sic], there is the force by which . . . single meanings tend to split up into a number of separate and often isolated concepts. . . . The second principle is one which we find given us, to start with, as the nature of language itself at its birth. It is the principle of living unity.”5

“ . . . Not an empty ‘root meaning to shine,’ but the same definite spiritual reality which was beheld on the one hand in what has since then become pure human thinking; and on the other hand, in what has since become physical light; . . . not a metaphor, but a living figure.”6

These passages could almost pass for a para-phrase of Cassirer’s Language and Myth, or frag- ments from the Philosophie der symbolischen Formen. The most striking parallel, however, is the discussion of mythic imagination, which begins: “Perhaps nothing could be more damning to the ‘root’ conception of language than the ubiquitous phenomenon of myth.” Barfield then states briefly the theory of multiple meanings and fusion of symbol and sense, and concludes:

“Mythology is the ghost of concrete meaning. Connexions between discriminate pheno-mena, connexions which are now apprehend-ed as metaphor, were once perceived as immediate realities. As such the poet strives, by his own efforts, to see them, and to make others see them, again.”7

Notes

1 Cassirer’s philosophy of symbolic forms developed out of his earlier work, Substance and Function.

2 The reference is to the works of John Locke, Max Müller, and Anatole France, respectively. Poetic Diction, A Study in Meanings, p. 57.

3 Hugh Blair, Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres (I783).

4 Barfield, op. cit., p. 70. Concerning the subject-object dichotomy, compare Cassirer, Philosophie der symbolischen Formen, II, p. 32 on the primeval function of symbolism: “Just because, at this stage, the ego is not yet conscious and free, flourishing in its own productions, but is only on the threshold of those mental processes which shall presently dichotomize ‘Self’ and ‘World,’ the new world of signs must appear to the mind as something absolutely, ‘objectively’ real.”

5 Ibid., p. 73.

6 Ibid., p. 75.

7 Ibid., pp. 78-79.

Langer main page