AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From The Hudson Review, Vol. III, No. 2, Summer 1950, 219-233. This should be read with her earlier “The Principles of Creation in Art.”

Posted June 26, 2008

The Primary Illusions and the Great Orders of Art

Susanne K. Langer

All art is the creation of forms expressive of human feeling, from the primitive sense of vitality that goes with breathing and moving one’s limbs, or even suddenly resting, to the poignant emotions of love and grief and ecstasy. The essential unity of the arts is vouched for by this large and single purpose, and really requires no other explanation. What is difficult to understand is the selective character of artistic talent. Few creative artists are equally gifted in even two realms of art. Leonardo, for all his versatility, was above all a painter; his poetry, from any other pen than the great painter’s, would hardly have stood the test of five hundred years. Wagner would certainly not have impressed his generation as poet or dramatist without his musical fame. William Blake, equally great as poet and painter, always comes to mind in this connection just because he is a notable exception to the rule. Talent is normally restricted to one artistic domain. No matter how positively we proclaim the identity of all arts, in practice we do not turn to Picasso for musical education, nor expect to learn painting from Kreisler, nor study ballet under T. S. Eliot. And that is not because the techniques are too specialized for one man to master; painting is technically as different from sculpture as it is from piano playing; but it is near to sculpture and far from piano playing, because the primary illusion it creates is virtual space, and what music creates is something else. Music is of a different order of imagination, and even if it were made with hammer and chisel on a stone that emitted sounds, it would be music, not sculpture.

The function of plastic art—”to make space visible, and its continuity sensible,” as Hildebrand stated it—has been generally overlooked, because a much less important but more obvious function commanded people’s first interest: imitation of things that are visible in actuality (which space is not). Music, too, is theoretically misunderstood because an obvious approach to it presents itself at once, and blocks our view of what a musician really creates. The wrong premises here are not as naive as the copy-theory of visual art, but they lead, I think, to an equally unenlightening analysis. They are, in brief, that the elements of music are tones, whose essential characters are pitch, duration, loudness, and timbre (tone-color depending on overtones); that these tones are combined by the composer to yield patterns of sound, characterized as melody, harmony, and rhythm. Complex patterns, exempli-fying all these characters, are works of music, which act upon our sensibilities, and stimulate our emotions. To “understand” a piece of music is to recognize its factors, which are, of course, more subtle than this bare outline indicates, but belong in the general categories here named.

What, then, is created in music? Apparently nothing; tones are produced, but tones are actual phenomena, and their somatic effects are actual, like the effects of contact with warm or cold objects, the smell of perfume, etc. According to this view, musical composition should be a science rather than an art. That theory has, indeed, been seriously entertained.

Yet music is the most enthralling, i.e. illusionistic, phenomenon in the world. What we hear in listening to sounds “musically” is not their specific pitch and loudness, duration and timbre. Often we are not even specifically aware of melody, harmony, or rhythmic figure, yet the music is perfectly meaningful. What we hear is what Hanslick has properly described as “tönend bewegte Formen”—“sounding forms in motion.” We hear movement and rest, swift movement or slow, stop, attack, direction, parallel and contrary motion, melody rising or soaring or sinking, harmonies crowding or resolving or clashing; moving forms in continuous flux.

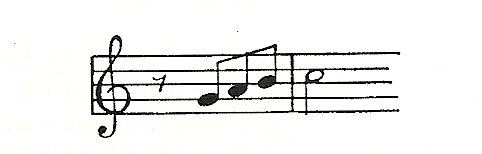

But in all this progressive motion there is actually nothing that moves. Here a word may be in order to forestall a popular fallacy: namely, that the motion is actual because strings or air-columns and the air around them move. But such motion is not what we perceive. Vibration is minute, very fast, and without direction—or rather, it s direction is back and forth, in an infinitesimal space. The motion of tonal forms, however, is large and directed toward some point of relative rest. In a simple passage like the following:

the three eighth notes progress up to the tonic C. But in actuality there is no thing that moves up. The C is their point of rest; yet physically there is faster motion during the time we hear the C than there was while we heard the three tones going up to it. The motion of sounding forms, like the forms themselves—everything, in fact, but the sounding—is sheer appearance, illusion. The forms are virtual, their motion is virtual, and the whole composition is a semblance.

Music is a semblance of Time in its passage. What it creates is an order of virtual time, defined and organized by the illusion of motion. Music makes time audible, and its continuity sensible. It does this by virtue of its basic abstraction, sounding forms in motion, or kinetic tonal forms.

Just as the space of experience is not the space of geometry, so experienced time is not the time we establish by clocks. Our actual subjective time-perception is even more composite, pragmatic, and incomplete than our space-perception. Clock time is a highly simplified abstraction from experienced time; scientific time is a refinement of clock time. Both share one basic formal property that results from the intellectual economy they serve—they are both conceived as having but one dimension. Modern scientific time, in fact, is one dimension of a greater relational construction.

All this is very far from time as we know it in direct experience, where it has many characteristics. Experiential time is essentially passage, or the feeling of transience. That is, I believe, what Bergson meant by “duration,” as opposed to scientific time which he regarded as “spatialized” and thereby falsified, because space seemed to him less real than time. Why space should be less real is hard to understand, but his doctrine has a true intent none the less: for “spatialized” time is time conceived through a metaphor from space experience, and the time-concept thus attained is “clock time” in the broadest sense, culminating in the useful but artificial construction we call “scientific time.” It is not based on the feeling of passage, but on the comparison of physical states and the observation of differences between them. States are ranged in an order of before and after; the contrasts they present are the measure of change. What lies between two states is not observed, but left vague, because its exact conception is unnecessary to the formalization of a measurable time. Just because actual passage is not conceived, “clock time” is homogeneous and simple and may be treated as one-dimensional.

Experiential time, on the other hand, is not simple at all. Besides the property we commonly call “length,” and treat as its one dimension, it has another that I can only denote, metaphorically, as volume. Subjectively, a unit of time may be great or small as well as long or short. The slang phrase “a big time” is psychologically more accurate than “a pleasant time” or “a quickly-passed time.” It is this voluminousness of the direct experience of passage that makes it, as Bergson says, indivisible. But even its volume is not simple; for it is filled with its own characteristic forms, as space is filled with material forms; and each order is really conceivable only because it is divided by the things in it, whereby it may be noted and measured. The forms that fill time are tensions—physical emotional or intellectual. Time exists for us because we experience tensions and their resolutions. Their peculiar building-up, and their ways of breaking or diminishing or merging into longer and greater tensions, make for a vast variety of temporal forms. If we could undergo only single, successive organic strains, perhaps subjective time would be one-dimensional, like the scientific time ticked off by clocks. But life is always a dense fabric of concurrent tensions, and as each of them is a measure of time, the measurements themselves do not coincide. This causes our time-experience to fall apart into incommensurate elements which cannot all be perceived together as clear forms. If one is taken as parameter others become “irrational,” out of focus, ineffable. Some tensions therefore, always sink into the background; some drive and some drag, but for perception they give quality rather than form to the passage of time, which unfolds in the pattern of the dominant and distinct strain whereby we are measuring it.

Subjective time is perceived in actual life only in a haphazard and confused way. For practical purposes we largely ignore it and let the formal measurements of the clock predominate, because they are designed pragmatically in the universal framework of astronomical events, so that we can all agree on them. Like actual space, which we measure in geometric abstraction or else accept vaguely as a mixture of views, things, and places, so actual time is either a scientific datum or a confused experience of physical and mental strains—of waiting, expectation, fulfillment, surprise. It has no unified perceptual form, no clear continuity.

The creation of a self-contained temporal order, continuous, all-inclusive, and entirely given in direct experience, is the business of music. The elements of music therefore are sensuous images of the tensions and resolutions which constitute passage for us; and those sensuous images, creating the semblance of passage, are tonal forms in virtual motion. By these the illusion of time is achieved and its experiential character set forth—its complexity, density, and volume, its interwoven elements and indivisible flow.

If, now, we turn to the standard analysis of music and are confronted again by the inventory of its constituents—tones having definite degrees of duration and pitch, by virtue of which they may be composed into rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic patterns, enhanced by variations of loudness and timbre—we see that this study begins with musical materials, not musical elements. But it lacks an adequate principle for admitting or excluding materials. The sounds of a snaredrum, which have neither definite pitch nor controllable duration, cannot really be classed as “tones” at all. Rhythm, supposedly their main contribution, is achieved by leaving exact intervals between them, i.e. by silences. Is silence to be a constituent? Moreover, there is music that loses much of its character when it is separated from words; but words, though they are sounds, make “musical” patterns only in a derivative sense, for they are not tones. Is such music a hybrid art?

Materials are actual, and their properties are fixed. Elements, on the other hand, are virtual, for they are constituents of the total semblance. The question of what is or is not a musical element is easily answered with reference to the primary illusion: anything is a musical element that enters into the illusion—that serves to create, support, and organize the virtual image of time. The materials of which musical elements are made may be tones or atonal sounds, silence, speech, even dramatic actions motivating changes of theme. There is no legislating as to what shall be material for music. Once the primary illusion has been experienced, there are many materials, and probably many primitive sources of the art it begets. The musical mind finds music everywhere—in speech, in nature, in the rhythms of work; and so it uses everything resonant, from the human voice to the bowstring and the hollow drum, to make the passage of time audible and its forms expressive.

There are certain kindred arts, that create the same primary illusion in different modes. The subject is too extensive to be introduced here, except to remark that—plausibly enough—sculpture and architecture stand in this relation to painting, and drama to literature. Music, also, is generally supposed to have a sister art, namely the dance. They have grown up together; and after many centuries in which music rose to the highest artistic levels and ballet sank to mere entertainment or ballroom exercise, our so-called “modern dance” is again a serious creative venture, and is generally regarded as a musical art. Some aestheticians, and even more significantly—some excellent dancers and choreographers, and a few musicians, maintain that exactly the same forms may be exhibited in tone as in bodily motion, so that the difference between music and dance is only a superficial one of appeal to hearing or to vision, as the case may be, like the difference between spoken and written language. The French music critic who calls himself Jean D’Udine says in his provocative little book, L’art et le geste: “All music is dance—all melody just a series of attitudes, poses.” Jacques-Dalcroze, who was a musician and not a dancer by training, regarded dance as a direct translation of music into bodily responses, so that any music could be “danced,” i.e., rendered precisely as a balletic pattern. Fokine undertakes to translate Beethoven’s symphonies into choreographic terms. And Sakharov writes in his Reflections on Music and the Dance: “I do not dance to music, I dance music.” The person who taught him to do this, he claims, was Isadora Duncan; she was the first serious artist who proposed to dance music itself, to interpret it, just as a virtuoso with his instrument interprets what the composer has written.

Isadora’s relation to music, however, is just what throws a serious doubt on the musical character of dance. An artist is usually incompetent judge of work in his entire realm, i.e., anywhere within the scope of the primary illusion of his art, even where that illusion appears in a special mode not his own. But dancers are not usually connoisseurs of music, and there are but few musicians who appreciate dancing at all. Isadora’s musical taste was simply mystifying. From the musician’s standpoint it was neither good nor bad, but unpredictable. She admired very good pieces and very bad ones; her favorite composers were Beethoven and Ethelbert Nevin. What she did with their works was always beautiful, but musical critics generally protested that she did not understand the music and flouted the composer’s intent.

The explanation is, I think, that her judgment was not musical, but balletic; and that very great and very poor music, alike, may have balletic value. Isadora’s feeling was so entirely for dance that she could find nothing else in music, and therefore believed that what she danced was the music itself, its very essence. This belief did not interfere with her art, but it did mislead and affront musical people, whose conceptions of Beethoven certainly were not reflected, let alone deepened, by her performance. Musicians generally resent the modern ballet just because they believe it to be a musical art, and then find that it adds nothing to music, but on the contrary distorts and abuses it.

The illusion created in dance—any kind of dance, from square dance or social dance to the Russian ballet—is neither that of music, i.e. virtual time, nor the virtual space of plastic art. Dance is a separate art, with its own primary illusion.

What, then, is dance? Those dancers who do not regard it as a representation of music generally define it as a spatial art, and conceive it either as a pattern of motions with moments of statuesque arrest, or else as a succession of poses, like tableaux vivants, connected by motions. This is the “classic” point of view, comparable to the conception of painting as arrangement of colors, and of music as the combination of consonant or dissonant tones. For in the dance, motion is actual, not illusory, and a pattern of motions taken simply as such is aesthetic rather than significant. There is another school, however, sometimes frowned upon as “impure” in its aim, that treats all balletic motion as pantomime, i.e., formalized imitation of acts. The histrionic content here is of course thematic, and if it monopolizes or even distracts the beholder’s interest it debases the dance. Imitation, however important to a particular piece, is never an essential factor in an art. Yet the dramatic theory has its virtues, for it presents balletic motion as gesture. This immediately sets dance apart from mobile sculpture, from the rhythmic movements of machines, the sinuous grace of a hunting cat, or the weaving of gnats in the air. Gesture is in some ways a broader term than motion, and in other ways narrower: broader, because a pose, a look, a moment of rigor may be a gesture without being a motion; narrower, because not all motions are gestures. Gesture is expressive behavior. In actual life it is often unconscious, symptomatic of emotions and impulses; an attitude of weariness, for instance, is a sustained unconscious gesture. But gesture may be deliberate, too, and practical (pointing, beckoning, warning, etc.), or even symbolic, supplementing language (as when one says: “A fish as big as that”). The deaf-mute alphabet is a completely discursive system of gesture; another, less articulate but more self-evident, is the sign language evolved by Indian and white scouts, in which the principle of symbolization is pantomime, stretched to great lengths of meta-phorical use.

Gesticulation, however, is not art; it is expression, subjective self-expression or objective logical expression as the case may be, but as long as it is essentially either emotive or practical it is not art. If gestures could convey nothing but literal ideas—“I throw a ball,” “the swan dies,” “this is the way we wash the clothes”—they would not lend themselves to artistic uses. But they are more than involuntary or semantic acts: they are forms of behavior. As forms they may be abstracted, and treated freely to create rhythms, indivisible lines of action, the appearance of challenge and response, the illusion of powers in conflict, in balance, or in union. And here we have the ruling principle—the primary illusion of balletic art: all dance creates a realm of virtual Power, an illusory field of forces involved only with each other, weaving a fabric of freely rhythmic, continuous and coherent gesture.

The forces presented in dance may be physical, psychical, mythic or magical, but they are always felt, not computed or inferred. They are not the actual forces that move the dancers, bodily energies limited by gravity and friction, but lures and excitements, prescribed paths, engulfing rhythms, personal wills—all orgiastic, mystical, or musical causes, virtual powers that evoke virtual activities. In watching a ballet one is not aware of people running around, but of the dance driving this way, drawn that way, gathering here, spreading there. In a pas-de-deux the two partners seem to magnetize each other. The relation between them is more than a spatial one; it is a relation of forces.

The most elementary means of abstracting motion from the work it actually performs is rhythm. This is a psychological factor, not an intrinsic property of mechanical motions, where there is uniformity, but no accent. We organize uniformities mentally into arsis and thesis, to and fro, tick and tock. Rhythmization transforms walking into marching, prancing into dancing; for it establishes a conceptual control over motion and gives it a clearly sensible form. As soon as we feel the rhythm of a march, it dominates our walking; we “fall into step.” Ballroom dancing is one of the simplest abstractions of motion from the purpose of locomotion, which becomes subordinate. Through rhythm, and the gestive form of the step, the partners are oriented toward each other, and this virtual relation links them even without any physical contact. Artistically such performance has very limited possibilities, yet it creates its own little realm of virtual power, and is genuine dance.

In higher phases of balletic art, real activities are often simulated, and enter into the pattern of gestures as pantomime, or dance-motifs. But in so doing they are always transmuted into mere appearances: in representing flight from a pursuer, the dancers do not actually run as they would at an alarm of fire, but retreat in a rippling toe-dance or even pirouetting, or withdraw with a mere leaning gesture—anything, in fact, except turning around and running. If the dance is successful, they seem to be driven by a menacing force and to be carried by emotion.

If we regard dance as the envisagement of a realm of Powers and the presentation of their interplay, we can readily understand why dance holds a supreme position in primitive culture, why it is universally linked with religion, and why it usually reaches its highest development before music is more than a rhythmic accompaniment to it, and before painting has risen above traditional designs on pottery and textiles or on the human body. Elaborate ritual dances are found where poetry does not yet seem to exist. The reason is that imaginary Powers—mana, taboo, magic, godhead and doom—are the realities of primitive life, but not the prosaic realities: they constitute a closed and sanctified realm, the spirit-world.1 The center of this world—the altar—is the natural focus of the dance, which symbolizes and celebrates such Powers. The altar is the virtual force that organizes the whole field, and around it or its equivalent—the idol, the priest, the totem—the dance develops. Pantomime usually supplies the motifs, as physical objects furnish motifs for painting and sculpture. The magic circle governed by the god is the ideal choric stage, and ritual a constant source of purely expressive actions, thematic elements that weave themselves naturally into dance.

The proposition that artistic symbols are non-discursive forms, presenting the morphology of sentience which discursive forms cannot express, meets its test case, of course, in the literary arts. Certainly literature is composed of discursive symbols; and just as certainly it contains more than a logically adequate statement of propositions. This is most evident in poetry. Many books have been written on the problem of poetic quality, and different thinkers have attributed it variously to word-music, to imagery, to suggested associations, and to value-judgments implied by the poet’s selection of things to dwell upon. Dream symbolism especially has been held responsible for poetic appeal.

Word-music is a factor in poetic composition, but it is not what makes poetry. The same is true of imagery, word-pathos, “criticism of life,” and dynamic” phantasy. Sound and sense, implication and suggestion, derivations and metaphorical meanings, grammar, accent, dialect, strong and weak word-forms—all are materials out of which the elements of poetry may be made. But those elements are as non-discursive as the painter’s perceptual objects, the musician’s sonorous moving forms, the dancer’s virtual forces. They are created, i.e., are illusions achieved by abstracting semblances from the actual world, and then composing these sheer appearances into new forms that mirror the logic of feeling.

The nature of literary creations is most readily illustrated in a simple experience with words that probably everyone has encountered: that a perfectly familiar fact seems perfectly terrible when stated a certain way. I do not mean in a certain tone of voice, but with a particular turn of phrase. Surely everybody has at some time been told: “It sounds so awful when you put it like that!” Or: “When you say it that way, it seems silly.” Or: “He made it sound simply wonderful.” One does not protest that the fact is so awful because of the presentation, but only that it seems, or “sounds,” that way. But one might say quite truly: “When you put it like that, it’s an awful thought!” The thought is awful, although the proposition remains just what it was. And here, I believe, is the principle of all literature, which is most evident in lyric poetry. Poetry asserts propositions only as thoughts. The same proposition may be thought in countless ways, and each way has its own emotional value. The proposition, which might be expressed in logical symbols, is related to the thought as a physical object is related to a visual form that portrays it. The thought is what the poet’s way of stating the proposition creates; the thought is a poetic element.

Our actual thoughts chase each other in haphazard fashion, so that their complete form rarely develops. We think and act without taking stock of the way events and phantasies, beliefs and proposals and expectations really present themselves; yet such experiences constitute our personal history. Like all actuality, that history is only half perceived, and half intellectually constructed. For practical purposes we do not need to remember an unbroken past, but only to reconstruct salient moments, that mark successive stations in the progression of events known as our “life.”

Literary art, by contrast, creates a completely “lived” piece of experience. The piece may be very small, like the brief thought that constitutes a lyric such as:

A slight disorder in the dress

Giveth to youth a wantonness—

But it is a thought really seen in its passage, followed through from its whimsical rise to the final pronouncement of taste that closes it. The idea is fully entertained, without being foiled by the incursion of other, perhaps more important thoughts; and it seems to be entertained actively, at the moment, though it was written more than 300 years ago. The reason is that it is the semblance of a thought; that is why we read it as something essentially timeless. The present tense, which is characteristic of lyric poetry, is really a “historical present,” for it makes no reference to the actual situation of the poet, but to an envisaged piece of life. In that context, events and acts seemingly take place as they do in actuality—but only seemingly; the experience of them is virtual, and the form of the illusory occurrences is as much simplified, organized, and composed as a picture. But such illusory events are not discursive propositions. The propositional material has been transformed into experiential elements in a created semblance of life.

This total semblance is, I think, what critics often refer to as the poet’s “vision.” I can find no other justification for that word. In the framework of the present theory, however, it is perfectly justified. A poem is essentially and entirely a creation; the words beget virtual elements, that exhibit forms of sensibility and emotion and thus carry a meaning beyond the discursive statements involved in their construction. But the meaning is not something to be read “between the lines”; it is in the lines, in every word and every punctuation mark as well as in the literal content of every sentence. The whole fabric is a work of art.

The first task that confronts an artist is always to establish the primary illusion, i.e., to close the total form and set it apart from actuality. That is the purpose of poetic structure—of meter, rhyme, divisions, repeated or imitated lines, and pure sound-effects like hey-nonny-no and daffy-down-dilly. How much of this artifice is needed depends on what other elements there are that will assure the “psychical distance” of the work. A heavy discursive content usually requires a strict poetic form, as for instance the sonnet; there is such a thing as a true sonnet idea, which calls for every device of fabrication, from word-music to interlacing rhymes, to keep the thought in the realm of imagination. If, on the other hand, great imagery and a certain unrealism of subject matter already perform this function, the poetic structure may be very free, as in the Psalms of David. In poetry as elsewhere, the means of creating virtual elements are various, and almost every one—sound allusion, imagery, archaism, dynamic sym-bolism, ambiguity, etc.—has its possible alternatives.

The most prevalent single device, probably the first to beget literature at all, is narrative. The image of experience is most readily obtained as we obtain it in actual life, namely as memory. Marcel Proust finds this to be, indeed, his only key to authentic composition, for memory leaves much out but intensifies what it retains, and usually completes its reconstructions of life by the principle of association rather than real causal connectedness. The process of intensification seems to him the essence of all poetic experience, and certainly there is much to be said for his analysis. Memory is formative, and produces perspectives of deeply felt events. In literature the unfolding of a story does the same thing. Even a simple narrative is such an organizing force that we usually speak of it as the “plot,” i.e., the ground plan, of the work in which it is utilized. Where the principle of narration enters into poetic structure all other devices have to adjust themselves: the choice of imagery is no longer free, as in the pure lyric, but is determined by the need of heightening some events and perhaps preparing others, and of slowing or hurrying the course of action. The descriptions of witch-fires and water snakes and “slimy things” in the Ancient Mariner make the story move with terrifying slowness while the ship is in doldrums. The same effect may ruin a work, where the story ought to move and is delayed by long descriptions introduced for their own sake, as in many romantic poems and novels. The verbal problem, on the other hand, becomes much simpler where narration holds the total structure together; the intensive poetic cadence that is the magic of the lyric is no longer needed, so a much simpler form, e.g., the colloquial language and regular meter of the ballad, may take its place. The prime virtue of story is that it constructs a much bigger span of experience than a presentation of entirely subjective events can effect. It creates in free and full scope the primary illusion of literature, which is a virtual Past.

As the lyric and the ode use the present tense to convey thoughts that are really timeless, so the ballad is normally in the past tense, because it achieves the illusion of history. The perfect tense is, in fact, characteristic of literature as a whole; the use of the present is a special device, for the semblance of experience made with words is always complete, like memory. But it is a powerful device, the historical present, and does not by any means always achieve “timelessness”; it may intensify a past event, as strong feeling intensifies memories to the point of making them almost eidetic, so people sometimes say: “It’s just as though it were now!”

The ballad is built on one straightforward story, and has therefore a fundamentally linear structure, reflected in its simple and fast-moving meter. There are broader planes that give one a sense of contemporaneousness of events, and consequently of history as a fabric rather than a sequence of actions. Such a design is the romance, which uses a new technique, namely a detailed account of how things are done instead of the mere statement of their occurrence. Here description serves for something more than to delight the imagination by dwelling on events; this being dwelled on gives the events new form—like the creation of visual forms suddenly in three dimensions instead of two. That, far more than the introduction of occasional contemporaneous happenings, gives the romance the appearance of a fabric instead of a thread of history. The descriptive principle, in fact, is so effectual that the persons in the story may be quite schematically rendered, human types rather than individuals, actors in a very colorful scene, like figures in a tapestry.

As the resources of narrative are developed, the office of pure diction, i.e., poetic statement, becomes less vital; the romance retains its literary virtue even in prose, as in the Spanish “novella.” Finally the full-fledged novel, the chief fictional work of our age, presents an entirely different appearance, for its most important creations are “characters,” individual human agents. These are so obviously its pivotal elements that popular judgment, and often even the professional critics, treat only the personalities in a novel as the author’s creations, and literary criticism is led into a new danger, namely that of regarding the novelist as essentially a psychologist, a reporter on typical human reactions. Any novel that presents a lifelike personality is likely to be hailed as great literature. The peripheral characters, the places, the impersonal events, all these are passed over. But in fact they are all cut out of the same cloth as the central personages. Not only the brothers Karamazov, but the dim figures of the Elder the lame little girl, the inn-keeper and the officers of the law are literary creations; if they are undeveloped it is not because Dostoevsky did not know their prototypes intimately enough to give them more articulate form, but because he because he really created, not copied, them—created their outlines as he needed them, without detail but with perfect truth. Furthermore, the inn, the garden, the days and nights are all creations—elements in a virtual Past which bears the stamp of vivid memory, yet is not anyone’s actual recollection.

The analysis of forms I have just presented leads from the simplest—the use of words to abstract the appearance and feeling of propositions as they figure in our thinking—to the very elaborate composition of virtual events filling a whole human consciousness, even an extended, imaginary “social consciousness.” Historically, however, the very complex was first; for all literary devices—rhythmic cadence, story, imagery, realism and supernaturalism and mythical symbolism, dramatic characters, lyric utterance, dialogue—all may be found in the epic, which is the cradle of literature.

All—yes; but not all at once. The epic is the matrix, for in its great structure there is a constant variety of forms due to the alternating use of techniques each of which produces its own perspective. The purer literary genders have been derived, I believe, by specialization, through the discovery that any principle may become central, and may, in fact, stand proxy for any other, given the circumstances. It is this possibility of alternating the techniques of creation that keeps the several forms (lyric, ballad, novel, biography, etc.) so closely related; but it also begets their multiplicity, which is presumably not exhausted yet.

Nothing has been said, so far, about that ancient and eminent art form, the drama; and in the compass of this essay little can be said, save that I believe the drama is not strictly literature at all. It has a different origin, and uses words only as utterances. It is a kindred art, for it produces the same primary illusion as literature, namely the semblance of experienced events, but in a different mode: instead of creating a virtual Past it creates a virtual Present. It is related to literature as sculpture and architecture are related to the graphic arts. But this categorical statement must remain an “aside”; our subject is already too great for the allotted pages.

In the scaffolding of this theory of art, which was derived by generalization from the more limited study of significant forms in music, the first result is a very radical setting apart of the major arts. Yet oddly enough, as soon as they are duly distinguished, their basic identity comes to light, because their respective principles, whereby each is an autonomous realm, are analogous, so their abstract formulations coincide, and make one set of propositions expressing the broad and universal principles of Art. But, to borrow Rudyard Kipling’s phrase, “That is another story.”

1 The dichotomy of primitive life into sacred and profane was noted and developed by Cassirer in Die Philosophie der symbolischen Formen, vol. 2. See also Language and Myth and An Essay on Man.

Langer main page