AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

From Lonergan Workshop, vol. 11, 1995, 53-90.

Posted May 5, 2008

What Bernard Lonergan Learned from Susanne K. Langer

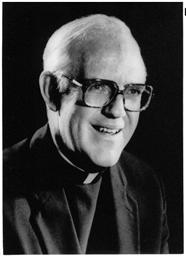

Richard M. Liddy

When I was asked to re-visit the subject of my doctoral dissertation about Susanne K. Langer, finished almost twenty-five years ago, I did not think that I would realize something new about myself—and about Bernard Lonergan. For I wrote my dissertation during a time when I was simultaneously wrestling with Lonergan’s thought. I was a young priest in Rome and the Second Vatican Council had just ended unleashing a great deal of change and turmoil in the Catholic Church. I was studying philosophy: chiefly, Bernard Lonergan’s philosophy on the one hand and, on the other hand, the work of Susanne K. Langer.

In Insight Lonergan had recommended Langer’s Feeling and Form on artistic and symbolic meaning and in subsequent writings had continued to recommend that work. But in the middle-1960’s, as I worked on my thesis, Langer published another major work entitled Mind: An Essay on Human Feeling.1 And when I figured out what Langer was saying in that latter work, I experienced a big shock. That work, the three volumes of which occupied the last years of Langer’s life, turned out to be a reductionist and materialist account of human mentality. Ultimately, it reduced all human mentality to feeling and feeling it reduced to electro-chemical events.2

The conflict that work set up in me became quite clear: who was right? Langer or Lonergan? And more importantly, what were the facts? It was quite an existential issue for me. Obviously, I came down on Lonergan’s side of that issue (but not without some soul—and mind—searching); and that is expressed in my dissertation.

But the point that comes home to me revisiting my thesis many years later is not so much about myself, but about Lonergan. The reason I got involved in Langer’s writings in the first place was that Bernard Lonergan had discovered something very positive in her writings, particularly in her major work on art, Feeling and Form. It was that work that he invariably recommended when he spoke of artistic meaning. And the point that has come home to me as I look back now is how often, in dealing with Langer and other writers, Lonergan accentuated the positive.

Insight was a major effort to “develop positions” and “reverse counter-positions.” What he did so often thereafter, as he read the existentialists and other contemporary writers, was the latter: to set whatever was right and true in an author within his basic positions regarding knowledge, objectivity and reality; and to let whatever did not fit within that context to fall by the wayside.

And that is what Lonergan did with Langer’s Feeling and Form. He repeatedly asserted that he had learned a lot from it; and that is the subject of this paper: what Lonergan learned from Susanne K. Langer.

According to Fred Crowe, Lonergan had not read Langer by the time he finished Insight in 1953.3 Before the final publication of the book in 1956, however, he had added two references to Feeling and Form, one a footnote to the section on the aesthetic pattern of experience regarding her analysis of musical insight; and a second note to the section on myth and allegory on the sensible character of the initial meanings of words.4

Yet after the publication of Insight, he gave particular attention to studying Feeling and Form, specifically in preparation for his lectures on education at Xavier University in Cincinnati in 1959. In March of that year he wrote to Fred Crowe:

On education course: plan to integrate stuff on existentialists with theory of Art in S. K. Langer (Feeling and Form), follower of Cassirer; eke out with Insight, for intellectualist, scientific side; throw in a bit of theology.5

Now somewhere Lonergan quotes C.S. Lewis to the effect that a good book is constituted by a good reader—and it seems to me that’s what happened between Lonergan’s serious reading of Feeling and Form in 1959, his translation of what he learned into his famous “notebook” and the giving of the lectures at Cincinnati, now published in the Collected Works as Topics in Education. In these lectures are found the most extensive treatment of art in Lonergan’s corpus, a whole chapter of 24 pages, the high point of a trajectory that goes from his two pages in Insight to the three pages in Method in Theology.6

That Lonergan considered Feeling and Form to be a very good book is quite evident from his positive references to it and from what was evidently his conviction that he owed his definition of art to her. As he writes in Method in Theology:

Here I borrow from Suzanne [sic] Langer’s Feeling and Form where art is defined as the objectification of a purely experiential pattern and each term in this definition is carefully explained.7

And yet the interesting thing about this statement of Lonergan’s and others like it is that this definition of art is nowhere to be found in Langer’s Feeling and Form! Langer indeed has a number of definitions of art, such as: “Art is the creation of forms symbolic of human feeling”; “Art is the creation of forms expressive of human feeling”; or “Art is the creation of perceptible forms expressive of human feeling.”8 And yet none of these are the definition of art that Lonergan continually attributes to Langer.

Which only goes to show, I believe, the creative transformation that the work of Langer—and other writers as well—went through, when Lonergan focussed on them. I have no doubt that Lonergan’s definition of art is clearer and leaner than Langer’s, because it is rooted in his own explanatory understanding of human interiority.

Thoroughly understand what it is to understand, and not only will you understand the broad lines of all there is to be understood but also you will possess a fixed base, an invariant pattern, opening upon all further developments of understanding.9

It was because Lonergan understood understanding that he was able to integrate into his own understanding the genuine insights of such diverse thinkers as Jean Piaget, Ludwig Binswanger, Gilbert Durand, Paul Ricoeur, Freud and Jung, Eliade and Voegelin, and so on—and in this particular case, Susanne K. Langer. In the writings of each of these authors, Lonergan was able to grasp what was of value, what was capable of development, on the one hand, and what was perhaps not so helpful, not capable of development on the other.

In the case of Langer’s Feeling and Form Lonergan was able to highlight and enrich his own understanding of art from the basic ideas and many illustrations, often from the writings and sayings of artists themselves, found in Langer’s work. At the same time he, of course, had no interest in the empiricist and reductionist leanings that I found scattered in Langer’s” early writings and highlighted in her later, Mind: An Essay on Human Feeling.

Let me add a word about the differing contexts of Lonergan’s writings on art and his references to Feeling and Form. In the first place, there is Insight. In that magisterial text the focus is on insight into insight; and his major examples are from science and mathematics, ‘the fields of intellectual endeavor in which the greatest care is devoted to exactitude and, in fact, the greatest exactitude is attained.”10 In that context, art is treated in the chapter on common sense as subject within the section on the aesthetic pattern of consciousness: the pattern that focusses of the joy of conscious living itself. As consciousness is free and can float in various directions determined by one’s interest, one’s care, so it can float in a direction guided by a care just to enjoy hliman experiencing for its own sake.

One is led to acknowledge that experience can occur for the sake of experiencing, that it can slip beyond the confines of serious-minded biological purpose, and that this liberation is a spontaneous, self-justifying joy.11

With respect to this field of aesthetic experience, the artist discovers “ever novel forms that unify and relate contents and acts of aesthetic~ experience.” Such insight into aesthetic patterns find expression, not in concepts, but in the work of art itself.

The artist establishes his insights, not by proof or verification, but by skillfully embodying them in colors and shapes, in sounds and movements, in the unfolding situations and actions of fiction. To the spontaneous joy of conscious living, there is added the spontaneous joy of free intellectual creation.12

After another two paragraphs on the symbolic or mysterious dimension of artistic creation, Lonergan quickly moves on to other patterns of experience, particularly the intellectual pattern of experience. But after having written Insight, where the goal is insight into insight, Lonergan gradually entered into a more existentialist and phenomenological context; he began to link what he had done on the intellectual side of things to the insights of various other writers into other areas of concrete human living.

Thus, in his 1959 lectures on education he sought to link his own insight into insight with what Piaget had learned about growing development in the human person, what Binswanger had learned about the dreams of night and the dreams of morning, and what Langer had learned about insight in the various forms of art. As he describes the aim olhis lecture on art in these 1962 lectures:

Neither mathematics nor natural science nor philosophy nor psychology is the same as life. I propose to seek an apprehension of concrete living in its concrete potentialities, through art today, and through history tomorrow.

He then speaks of all differentiation of consciousness as simply a withdrawal for a return.

It is withdrawal from total activity, total actuation, for the sake of a fuller actuation when one returns. What one returns to is the concrete functioning of the whole. In that concrete functioning there is an organic interrelation and interdependence of the parts of the subject with respect to the whole, and of the individual subject with respect to the historically changing group. Art mirrors that organic functioning of sense and feeling, of intellect not as abstract formulation but as concrete insight, of judgment that is not just judgment, but that is moving into decision, free choice, responsible action.13

Lonergan, as always, is thinking of the good as the conscious developing subject; the subject with his concerns that defines the various horizons of his world. It is in this context that Lonergan read Langer’s Feeling and Form and translated what he read there into his own thought and vocabulary.

In what follows in our paper we will stick closely to the text of Feeling and Form, chiefly because that is the text that Lonergan refers to when he speaks of artistic and symbolic meaning and this is the text he is thinking of when he said “I think Susanne Langer has a wonderful analysis of artistic creation.”14

Our method will be more that of an interpreter than that of a systematic presenter. Lonergan more than adequately, I believe, did the latter.

Susanne K. Langer

Philosophy in a New Key (1941)

Susanne Knauth Langer was born on the upper west side of Manhattan in 1895 to German immigrant parents. Her father, a lawyer, played the cello and the piano, and as a child Susanne learned to play both instruments. Her future writings on art, therefore, are from the point of view of someone who loved to play and to listen to music.15 In 1920 she obtained her bachelor’s degree from Radcliffe College; in 1924 a masters in philosophy from Harvard; and in 1926 a doctorate from Harvard in 1926, writing her dissertation on the topic: “A Logical Analysis of Meaning.”

Because of the times, her early philosophical work took place in the context of Anglo-American logical philosophy. This is obvious in her early works, The Practice of Philosophy of 1930, and her Introduction to Symbolic Logic of 1937. She was particularly influenced by Bertrand Russell, the Wittgenstein of the Tractatus and her own mentor at Harvard, Henry M. Sheffer. It was Sheffer, she says, who interested her in the “unlogicized” areas of mental life and in the relationship between the complicated symbols of mathematical logic and, on the other hand, other areas of human symbolization, such as ordinary and literary language, myth, ritual and art.16 The conventional positivist wisdom of the day tended to relegate all these areas to the non-scientific and therefore non-intellectual, “emotional,” dimension of the human person.

Consequently, in 1941, contrary to such positivist views, Langer in her very popular Philosophy in a New Key, vindicated the properly intellectual character of the non-discursive “presentational” symbols of myth, ritual and art. Under the influence of the neo-Kantian, Ernst Cassirer, Langer pointed to the highly “formal” character of these nonscientific expressions. Art, for example, is not just the symptomatic expression of the artist’s immediate emotion aimed at the stimulation of immediate emotion in the percipient; it involves a stylized “formal” quality, an element of “psychic distance” that constitutes it as properly human.

Cassirer had emphasized this formal, symbolic, quality in art and other ‘symbolic forms.” Such forms are distinguished from merely “passive images” in that they are not just given, but are created by the human mind itself. Hence, an historic and analytic study of these various symbolic forms—language, myth, religion, art—can provide a “phenomenology of human culture,” the human person’s ongoing discovery of himself.17

Langer calls these non-scientific symbols “presentational” because their materials are the ordinary presentations of eye and ear, of sense and imagination.18 They are the sensitive or imaginative forms, the Gestalten, of art, the gestures of ritual and the imaginative picture stories of fairytale and myth. These include not just the elements of sense and visual imagination, but materials of aural, kinaesthetic and literary imagination as well.

To these sensitive or imaginative elements meaning or import accrues. Although, in this writer’s opinion, Langer never successfully determined the meaning of meaning, nevertheless she was insistent on the human and “meaningful” character of these presentational symmbols.19 For unlike mere signals which are rooted in biological reflexes and are symptomatic of immediate emotional conditions, symbols are, as she puts it, vehicles of conception.20 They are highly “charged” with human formulated significance. In Philosophy in a New Key Langer analyzes art, especially music, as symbolizing the complexity of human feeling; ritual as symbolizing the human person’s permanent attitude or orientation among the terrifying forces of nature and society; and myth as the serious envisioning of the fundamental concepts of life.

The key term in the transition of Langer’s interest from the symbolism of logic to these other presentational symbols was the term “form,” the basis, according to the early Wittgenstein, of the symbolic character of language. In the Tractatus, for example, he uses an image that Lonergan also would invoke:

There is a general rule by means of which the musician can obtain the symphony from the score, and which makes it possible to derive the symphony from the groove on the gramophone record, and using the first rule, to derive the score again. That is what constitutes the inner similarity between these things which seem to be constructed in such entirely different ways.21

But unlike Wittgenstein, Susanne Langer was unable to abstain from questions of psychology. In seeking an explanation for the possibility of non-linguistic symbolism, she turned to the school that seemed most to emphasize “form,” that is the Gestalt psychologists of Wertheimer, Kohler and Koffka. These emphasized the fact that concrete sense experience is itself a process of perceiving total forms. Where previous experimental psychology assumed individual isolated impressions which by a process of association coalesce to form a totality, the Gestalt psychologists emphasized the primacy of form, ‘the whole,” over individual impressions in perception. As Langer wrote in Philosophy in a New Key:

Unless the Gestalt-psychologists are right in their belief that Gestaltung is of the very nature of perception, I do not know how the hiatus between perception and conception, sense-organ and mind-organ, chaotic stimulus and logical response, is ever to be closed and welded. A mind that works primarily with meanings must have organs that supply it primarily with forms.22

In Topics in Education Lonergan takes up this theme of the formative aspect of human perception. As the human person moves from the disordered and chaotic “dreams of night” to the “dreams of morning,” the selective character of human perception becomes more pronounced.

The difference between the dream of morning and the dream of night that is under the influence of digestive functions and organic disturbances is that there is more pattern to the dream of morning. Consciousness is a selecting, an organizing. And being awake is more organized than the dream of morning. Patterning is essential to consciousness. If one hears a tune or a melody, one can repeat it; but if one hears a series of street noises, one cannot reproduce them. The pattern in the tune or melody makes it more perceptible, something that consciousness can pick out and be conscious of, so to speak. Similarly, verse makes words memorable. One can remember ‘thirty days has September, April, June, and November,” because there is a jingle in it, a pattern to it.23

Lonergan’s point—and Langer’s—is that artistic meaning is found only in the symphony: that is, in the concrete pattern of the musical sounds. There may also be an external relationship, for example, between a representative painting and the object represented; but that relationship as such does not constitute the work as artistic. Freudian psychologists and others who delight in “explaining” art in terms of the subconscious motivations of the artist in representing certain objects fail to grasp the specifically aesthetic level of concrete experiential pattern. As Langer puts it:

Interest in represented objects and interest in the visual or verbal structures that depict them are always getting hopelessly entangled. Yet I believe artistic meaning belongs to the sensuous construct as such; this alone is beautiful, and contains all that contributes to its beauty.24

Feeling and Form (1953)

Langer’s classic work on art, Feeling and Form, published in 1953, is a development of the theory she began in Philosophy in a New Key. Here her approach is much less genetic and historical, in terms of the origins of art, and more analytical in terms of the concrete and operative elements in artistic consciousness.

The unifying term between the two works is, of course, form: that is, a pattern, a concrete set of internal relations between, for example, the colors and qualities of a picture; the proportionate importance of events in a drama, the ratios of musical motion.25 Langer uses many terms to designate the precise character of this concrete unified whole that is the work of art. In the following sections we will consider it as ‘the aesthetic illusion”; as “vital form” (that is, articulated according to the forms of feeling); and finally, as “commanding form” (that is, under the control of free human creativity). We will also add sections on the creative process and on the principles of artistic and symbolic imagination.

1. The Aesthetic Illusion

In Feeling and Form Langer develops her conviction that the meaning or “import” of art belongs to ‘the sensible construct as such,” the pure perceptible form. She does this by speaking of the aesthetic world as the realm of “illusion,” and less frequently, “appearance” or “semblance.”

By characterizing the aesthetic as illusion Langer does not intend to contrast the realm of art with that of reality as such, but only to contrast it with the realm of practical reality.26 Accordingly, aesthetic illusion implies, first of all, the liberation of perception from servitude to the realm of practical interests, and secondly, the concentration of attention on that world which, from the viewpoint of practical interest, is a world of illusion, of “mere appearances.” That new world is a world in which perception is its own end and finds its own line of development.

Langer notes the common sense conviction that the aesthetic and artistic always have the character of strangeness, otherness.27 Since “one’s world” is determined by one’s interest, attention, care, this “otherness” implies a shift of attention away from the ready-made world of normal living: in Coleridge’s terms, ‘the world of selfish solicitude and anxious interest.”28 It implies a shift of attention from the world of practically interesting ‘things” to the world of “appearances as such.” The world of appearances, of shapes, sounds, colors, and so on, is always a possible object of interest; for even so non-sensuous a thing as a fact appears this way to one person and that way to another.29

Nevertheless, we are usually not interested in the world of appearances. Appearances are valued only as indications of the ‘things” in question. Entering a room in normal daylight, we notice its contents, a red sofa, for instance; but we tend not to notice the gradations of red or even the appearance of other colors caused by the way the light strikes the sofa at that particular moment.30 Langer illustrates our customary obliviousness to appearances with the following quote from Roger Fry:

The needs of our actual life are so imperative that the sense of vision becomes highly specialized in their service. With an admirable economy we see only so much as is needful for our purposes; but this is in fact very little, just enough to recognize and identify each object or person; that done, they go into our mental catalogue and are no more really seen. In actual life the normal person really only reads the labels as it were on the objects around him and troubles no further. Almost all the things which are useful in any way put on more or less this cap of invisibility.31

Nor, according to Langer, is this freedom from practicality maintained by considering the aesthetic the realm of “make believe.”

The function of artistic illusion is not “make-believe,” as many philosophers and psychologists assume, but the very opposite, disengagement from belief—the contemplation of sensory qualities without their usual meanings, of “Here’s that chair,” ‘that’s my telephone,” etc. The knowledge that what is before us has no practical significance in the world is what enables us to give attention to its appearances as such.32

Not only is the aesthetic experience a liberation from the cares of practicality, it is also a liberation from intellectual constraints.

The free exercise of artistic intuition often depends on clearing the mind of intellectual prejudices and false conceptions that inhibit people’s natural responsiveness. If for instance a reader of poetry believes that he does not “understand” a poem unless he can paraphrase it in prose, and then the poet’s true or false opinions are what makes the poem good or bad, he will read it as a piece of discourse, and his perception of poetic form and poetic feeling are likely to be frustrated . . . Similarly, if academic training has caused us to think of pictures primarily as examples of schools, periods, of the classes that Croce decries . . . we are prone to think about the picture, gathering quickly all available data for intellectual judgments and so close out and clutter the paths of intuitive response.33

Langer often expresses the liberating character of the aesthetic and artistic by speaking of the essentially “abstract” character of the aesthetic illusion; and by this she means its separation from every other world, particularly the world of practical interest.

All forms of art, then, are abstracted forms; their content is only a semblance, a pure appearance, whose function is to make them, too, more apparent—more freely and wholly apparent than they could be if they were exemplified in a context of real circumstance and anxious interest. It is in this elementary sense that an art is abstract. Its very substance, quality without practical significance, is an abstraction from material existence . . . This fundamental abstractness belongs just as forcibly to the most illustrative mural and most realistic plays, provided they are good after their kind, as to the deliberate abstractions that are remote representations or entirely non-representational designs.34

As this abstraction, or separation, from other worlds takes place, a “new world” emerges. Langer’s most frequent illustration is from pictorial art. The “image created by the painter on the canvas does not take its place as a new ‘thing” beside the other things in the studio.”35 The painter has added nothing to the paints and the canvas. And yet, through his disposition of the paints on the canvas the created image begins to emerge, and this image seems to abrogate the very existence of the canvas and the paint. With the emergence of the artistic semblance these concrete materials become difficult to perceive in their own right. Perception is liberated from the world of practical materials—of canvas and paint.36

Consequently, when Langer speaks of illusion as the very “stuff” of art, the “new dimension” in which the artistic form is presented, she means not only the liberation of perception from servitude to practical interests, but also the entry of perception into its own world of pure sensation, pure imagination, pure perception. This is the result of the liberation of perception from all other interests and other worlds; and this is what is implied by saying that aesthetic meaning belongs to the sensuous construct as such, the pure perceptible form, sheer visions or images, and that appearances are appreciated for their awn sake and not as indications of the ‘things” in question. All such expressions in Langer’s writings imply that the very being of aesthetic and artistic forms is to be perceived. As she puts it, ‘they exist only for the sense or imagination that perceives them.”37

The perceptible character of an aesthetic form is its entire being. Thus, with regard to pictorial art,

The surest way to abstract the element of sensory appearance from the fabric of actual life and its complex interests, is to create a sheer vision, a datum that is nothing but appearance and is indeed avowedly an object only for sight . . . That is the purpose of illusion in art: it effects at once the abstraction of the visual form and causes one to see it as such.38

Now one of the fundamental convictions of Lonergan’s epistemology is a conviction first formulated by Aristotle: that knowledge is primarily by identity between the knowing and the known. Only secondarily, with the differentiation of consciousness does there arise the clear distinction between subject and object. As Aristotle put it, sense in act is the sensible in act, and intellect in act is the intelligible in act. Lonergan speaks of this initial stage as the stage of elemental meaning, prior to the clear distinction of a meaning and a meant. Such is the meaning of the work of art as described by Langer. As Lonergan puts it:

Some people will say that art is an illusion, others that art reveals a fuller profounder reality. But the artistic experience itself does not involve a discussion of the issue. What we can say is that it is opening a new horizon, it is presenting something that is other, different, novel, strange, new, remote, intimate all the adjectives that are employed when one attempts to communicate the artistic experience.39

According to Langer, each of the art forms have their own primary illusion: that is, they exist in their own realm of liberated perception.40 The orientation of a particular area of perception, away from other worlds, particularly the world of practical activity, introduces it into a world of its own, its own “virtual” realm of illusion.41

For example, in the plastic arts vision enters into a realm of “virtual space,” liberated from its normal practical orientation within common sense space.42 Common sense space is gradually constructed by the collaboration of the various senses, sight, hearing, touch, and so on, supplemented by “memory, recorded measurements, beliefs about the constitutions of things,” and so forth.43 The plastic arts, on the other hand are constituted by an orientation into a realm that is purely visual, and in which all the constitutive elements are purely visual.

Pigments and canvas are not in the pictorial space; they are in the space of the room, as they were before, though we no longer find them there by sight without great effort of attention. For touch they are still there. But for touch there is no pictorial space. The picture, in short, is an apparition. It is there for our eyes but not for our hands, nor does its visible space, however, great, have any normal acoustical properties for our ears. The apparently solid volumes in it do not meet our commonsense criteria for the existence of objects; they exist for vision alone. The whole picture is a piece of purely visual space.44

Painting creates a realm Langer calls “virtual scene.” Sculpture and architecture are other modes of virtual space creating the illusions of volume in space and the arrangement of space. She speaks of sculpture as creating the illusion of kinetic volume and architecture as creating the illusion of “ethnic domain,” a “world” that is the counterpart of the “self” whose semblance of kinetic volume is created in sculppture.45

The inter-related shapes and volumes of a picture or a piece of sculpture define an autonomous realm of space, which is purely visual. Within this space forms are constructed and ordered so as to arrive at a complete “shaping” of a given visual field; it is “infinitely plastic,” whether in two or three dimensions. Lines, which in common sense space indicate a relationship among ‘things”—fore-shortening—in art serve only to mediate between the several layers of design in a complex visual space. In his lecture on education Lonergan refers to the following quote from Adolf Hildebrand, found in Langer:

Let us imagine total space as a body of water in which we may sink certain vessels, and thus be able to define individual volumes of water without, however, destroying the idea of a continuous mass of water enveloping all.46

Music, on the other hand. creates an entirely different illusion which Langer calls “virtual time,” totally different from the abstract clock time by which we measure our lives. Music is created for the sense of hearing alone and consists in movements, tensions, resolutions and even “rests” that create a virtual world into which the musician helps us enter.

Dance creates the primary illusion of “virtual powers,” that is the visual expression of “wills” in conflict and resolution.

In watching a dance, you do not see what is physically before you—people running around or twisting their bodies; what you see is a display of interacting forces, by which the dance seems to be lifted, driven, drawn, closed, or attenuated. The physical realities are given . . . but in the dance they disappear; the more perfect the dance, the less we see its actualities. What we see, hear and feel are the virtual realities, the moving forces of the dance, the apparent centers of power and their emanations, their conflicts and resolutions, life and decline, their rhythmic life.47

Literature creates an illusion of virtual life, of memory as in lyric poetry, myth, legend or the novel. The drama introduces a person into the experience of the impending future, tragic or comic as the case may be. And the film extracts us from the present world and introduces us into another created present world—a quasi dream-world experience into which we too can enter.

2. Forms of Feeling

According to Langer, these purely perceptible forms are expressive of human feeling. They not only involve the exclusion of other practical and intellectual cares, but they also involve a release into their own line of development, determined by a retinue of affects and feeling. This accounts for the peculiar “logic” of artistic patterns, with their own proper rhythm of tensions and resolutions, their increasing variation and complexity within a unity. This is why artists speak of works in organic terms, noting the “life” in the patterns of a particular painting, while another kind of work is said to be “lifeless” or to contain “dead-spots.”

In Feeling and Form Langer takes the case of pure design as a touchstone for her explanation of this “vital” character of art. She notes that all over the world in such unrelated cultural products as Chinese embroideries, Mexican pots, Negro body decorations, and English printers’ flowers, one finds an astonishing similarity in basic decorative forms and designs. The vital character of these forms—lines and zigzags, circles and scrolls, balanced and repeated—can easily be seen by comparing them with strictly geometrical forms.48 These latter, all defined and expressed with geometrical exactitude, invariably seem “empty,” “dead,” “unfelt.” Pure design, on the other hand, with no representative intent, gives the semblance of “movement,” “growth,” life,” “feeling.”

Langer roots this life of purely perceptible forms in what Albert Barnes called our “general need of perceiving freely and agreeably . . . the need of employing our faculties in a manner congenial to us.”49 In Feeling and Form she notes that this congeniality finds an “instinctive basis in the principles of perception.” Previously, in Philosophy in a New Key, she noted that in music we deal with “free forms following inherent psychological laws of rightness.”50 These psychological laws and principles determine a certain inevitability in aesthetic form, making it “necessary” or “inviolable.” They are the foundations from whence springs the “decorum” or “fitness” of decoration, for example. Langer’s general term for these principles of free perception is ‘the forms of feeling.”

In Langer’s earlier aesthetic writings there is an implied dichotomy between the forms of perception, “purely perceptible forms,” and ‘the forms of feeling.” But her later writings tend to erase that trend and emphasize the close connection between the two elements in such a way that the proper character and development of purely perceptible forms is intimately rooted in the forms of feeling. The beginning of this emphasis can be found in Feeling and Form where she says of the aesthetic object that “It gives us forms of imagination and forms of feeling inseparably.” 51

In emphasizing the “organic” character of aesthetic form, Langer notes, for example, the rhythmic character of works of art: the consummation of one event is simultaneously the preparation for another, creating the setting up of new tensions by the resolution of former ones. Thus, in our paradigm case:

Decoration may be highly diversified or it may be very simple; but it always has what geometric form, for instance, a specimen illustration in Euclid, does not have—motion and rest, rhythmic unity, wholeness. Instead of mathematical form, the design has—or rather, it is—”living” form, though it need not represent anything living, not even vines or periwinkles.52

The effect of this “life” within each of the primary illusions is to make the perceptible forms more perceptible.

The immediate effect of good decoration is to make the surface, somehow, more visible; a beautiful border on textile “not only emphasizes the edge but enhances the plain folds, and a regular allover pattern, if it is good, unifies rather than diversifies the surface. In any case, even the most elementary design serves to concentrate and hold one’s vision to the expanse it adorns.53

3. Created Forms

We have been speaking about what Lonergan would call Langer’s descriptions of aesthetic forms as purely experiential patterns. But, according to Langer, art includes, besides this purely experiential element, the further element of its objectification, what we call “works of art.” This connects with her early recognition of the intellectual character of the various presentational symbols. For artistic creation involves, not just feeling-influenced experience, but the idealization of experience, the grasp of what is important from this perspective as important, and its expression or objectification in a work of art. Such objectification is a properly human and necessary element in art; for prior to this the aesthetic patterns are not fully and humanly known—not even to the artist himself.54

Objective expression is necessary for the artist to “hold,” to “fix,” to “contemplate,” to “understand,” the forms of his free aesthetic experience and feeling.55 The artist’s aim is to recreate in the concrete work of art a pattern isomorphic with his own idealized free aesthetic experience.

There is, therefore, in art an intellectual component that makes it comparable to another uniquely human objectification, that is, language. Art, in fact, belongs to the same category as language. The appreciation of a work of art involves a mental shift as definite and radical as the change from hearing the sound of squeaking or buzzing to hearing speech, when suddenly in the midst of “insignificant” surrounding noises a single word is grasped. The whole character of our hearing is transformed, the medley of physical sounds disappears, the ear receives language, perhaps indistinct by reason of interfering noises, but struggling through them like a living thing.56

The work of art effects the same sort of reorientation. Just as sounds become words by reason of their “meaning,” so colors on a canvas become a painting because of its artistic significance or “import.” This import permeates the whole structure of the work and separates it from the host of surrounding “insignificant” objects.57

Consequently, the “otherness” of the artistic is due not only to its aesthetic character whereby experience, liberated from other patterns, lives its own life; but also to the fact that it has been “created” by human intelligence and invites human intellectual apprehension. Langer is quite clear in asserting that art involves not only the level of perception and experience, but also the level of insight, understanding, contemplation. ‘the aim of art is insight, understanding the essential life of feeling.”58 The artistic symbol, qua artistic, negotiates insight, not reference.”59

Analyses of art very frequently fail to take into account this intellectual character. On the contrary, they consider art chiefly in terms of immediate experience and/or, most frequently, immediate emotion. It is in opposition to this trend, characterized occasionally as “empiricist,” “positivist,” “behaviorist,” that much of Langer’s early work was written; the insufficiency of this tendency is in fact the major emphasis in the chapters on art in Philosophy in a New Key and in Feeling and Form.

The history of art has been the history of artists’ efforts to attain ever more integrated, disciplined, and articulated forms. Sheer emotional self-expression requires no such effort and is in fact an obstacle to artistic creativity.

An artist working on a tragedy need not be in personal despair or violent upheaval; nobody, indeed, could work in such a state of mind. His mind would be occupied with the causes of his emotional upset. Self-expression does not require composition and lucidity; a screaming baby gives his feeling far more release than any musician, but we don’t go into a concert hall to hear a baby scream; in fact, if that baby is brought in we are likely to go out. We don’t want self-expression.60

Nor does the appreciation of art consist in the achievement of some rarefied “aesthetic attitude” or “aesthetic emotion” in the percipient. It is neither sheer catharsis or incitement.61 Langer contends that most art critics tend to discount both these “subjective” elements and treat the emotive aspect of a work of art as something as “objective” as the physical form or pattern itself. The “mood” of a painting is taken as given with the painting, totally penetrating it along with its sensuous qualities. People in the closest contact with art can appreciate this feeling without themselves cultivating an emotional “aesthetic attitude.” A quick glance at a page can tell them whether or not a poem is successful, “expressive” even though “the light of one bare bulb makes the room horrid, the neighbors are boiling cabbage, and our shoes are wet.”62

According to Langer, this degradation to “mere human sympathy” is what Edward Bullough would call a loss of “psychical distance.” Bullough describes the character of this relation in the following way:

Distance . . . is obtained by separating the object and its appeal from one’s own self, by putting it out of gear with practical needs and ends. But . . . distance does not imply an impersonal, purely intellectually interested relation. On the contrary, it describes a personal relation, often highly emotionally colored, but of a peculiar character. Its peculiarity lies in that the personal character of the relation has been, so to speak, filtered. It has been cleared of the practical, concrete nature of its appeal.63

Such artistic distance is such that the artist need not have directly experienced himself the feeling he represents in his art.

It may be through the manipulation of his created elements that he discovers new possibilities of feeling, strange moods, perhaps greater concentrations of passion than his own temperament could ever produce, or than his fortunes have yet called forth.64

In handling his own creation, composing a symbol of human emotion, he learns from the perceptible reality before him possibilities of subjective experience that he has not known in his personal life.65

Nevertheless, this artistic distance is not to such an extent that it bears no relation at all to the artist’s experience.

But to say that he does not render his own emotions would be simply silly. All knowledge goes back to experience; we cannot know anything that bears no relation to our experience. Only, that relation may be more complex than the theory of direct personal expression assumes.66

Art involves, then, the intellectual creation of an affect-laden image free from immediate emotion. As Langer puts it:

There are usually a few philosophical critics . . . who realize that the feeling in a work of art is something the artist conceived as he created the symbolic form to present it, rather than something he was undergoing and involuntarily venting in an artistic process. There is Wordsworth who finds that poetry is not a symptom of emotional stress, but an image of it—“emotion recollected in tranquility;” there is a Riemann who recognizes that music resembles feeling, and is its objective symbol rather than its physiological effect; a Mozart who knows from experience that emotional disturbance merely interferes with artistic conception.67

The choice of the term “artistic conception” is perhaps not a happy one, for it suggests expression in concepts and that is a characteristic of literal, not artistic, meaning; and Langer herself in her later work agreed with Kant’s analysis of art as non-conceptual.68 Nevertheless, her point is that artistic imagination is freely directed by, under the control of, impregnated with, the intellectual character of artistic insight.

In Feeling and Form Langer uses musical creation to give a description of the creative process, based on an intellectual grasp of the fundamental aesthetic form.69 First of all, this grasp is rooted in artistic genius, which Langer clearly distinguishes from talent. The latter is the basic ability to handle the sensuous materials, something closely linked with bodily feeling, muscular control, and soon. Artistic genius, on the other hand, is not just a higher degree of talent; it is the power to grasp—or as she puts it, to “conceive”—the “commanding form,” the matrix of the work-to-be, its general structure, the proportions and degrees of elaboration among the qualities of a picture, the events of a drama, the ratios of musical motion, an so on.70 Langer speaks of artistic genius with respect to artistic creativity; and such creativity certainly has an influence on the prior selectivity of artistic perception.

Prior to artistic conception or “insight,” artistic genius, it would seem, anticipates this activity. This is why the artist first contemplates his materials to see what feeling they might express. For different materials mediate different areas of aesthetic experience.71 This anticipation is not proper just to the artist; it characterizes any lover of art.

The outstanding instance of what one might call “intuitive anticipation” is the excitement that seizes a real lover of drama as the curtain goes up.72

It would seem that this a priori intellectual orientation toward the grasp of aesthetic form constitutes a certain artistic heuristic structure. Furthermore, since there are various primary illusions, various areas of aesthetic experience to be unified by artistic insight, it would seem that in each of these areas there are corresponding artistic heuristic structures. This seems to be the ultimate interpretation of Langer’s various primary illusions. This seems to be why de facto we have the various art forms that we do.

A great part of Langer’s work can be seen as a clarification of the nature of these structures, these various art forms. In each area experience seeks liberation. If, for example, one’s anticipation is practically oriented with regard to pictorial art, or purely literally oriented with regard to poetry, one will necessarily be led to misconceive and misapprehend this particular art.

With regard to music Langer notes the same frustrating influence of alien intellectual apprehensions.

The listener, untroubled by self-consciousness and an intellectual inferiority complex, should hear what is created to be heard. I think the greater part of a modem audience listening to contemporary music tend to listen so much for new harmonies and odd rhythms and for new tone-mixtures that they never conceive the illusion of time made audible, and of its great movement and subordinate play of tensions, naively and musically at all.73

Genuine artistic anticipation, this a priori ability for free artistic creativity, unencumbered with false psychological or theoretical anticipations, can deepen and develop. Thus, practice in sustaining musical attention results in “a special intelligence of the ear” capable of grasping the “logical connectedness” and progression of tonal sequences.74 This ability makes it possible to follow with easy attention extended or involved musical compositions. Langer contrasts this ability with mere passive hearing, equated with inattention.

The radio of course, offers all the means of learning to listen, but it also harbors a danger—the danger of learning not to listen; and this greater perhaps, than its advantage. People learn to read and study with music—sometimes beautiful and powerful music—going on in the background. As they cultivate inattention, or divided attention, music as such becomes more and more a mere psychological stimulant or sedative. In this way they cultivate passive hearing, which is the very contradiction of listening.75

This growth in artistic attention in the various areas of aesthetic perception is the primary pre-requisite for the exercise of artistic genius.

Thus, listening is the primary musical activity. The musician listens to his own idea before he plays, before he writes.76

4. The Creative Process

Artistic imagination exercises itself in the free creation of aesthetic forms. This is why artists are said to “contemplate” the aesthetic materials or medium. By the use of their free imagination they search out “the feeling it contains,” the aesthetic forms this particular material can possibly express. For different materials are said to have different feelings.77

A competent painter, accepting a commission for a portrait, a mural, or any other “kind” of work, simply trusts that, contemplating the powers of the medium, he will have a sudden insight into the feeling it can express; and working with it, he will pursue and learn and present that feeling. What he is likely to say, however, is that if he thinks about the commissioned subject long enough, he will know “what to do with it.”78

It is obvious then that it is in the artist’s free imagination that the materials are “transformed” into artistic forms. Because the artist can imagine the sensuous materials according to his aesthetic anticipation, he is said to perceive the materials selectively. It is imagined aesthetic perception, guided by artistic creativity, that Langer is speaking of when she says that the primitive portrays practical objects according to “the selective, interpretative power of his intelligent eye.”79 Similarly, Cezanne claimed that he was faithfully representing “Nature,” but it is obvious from his writings that he is speaking of nature transformed by his creative imagination.

In Cezanne’s reflections, that always center on the absolute authority of Nature, the relation of the artist to his model reveals itself unconsciously and simply: for the transformation of natural objects into pictorial elements took place in his seeing, in the act of looking, not the act of painting. Therefore, recording what he saw, he earnestly believed that he painted exactly what “was there.”80

It is with reference to imaginative “inward hearing” that the intellectual grasp of musical form takes place. That the imaginative “inward hearing” of the composer is grounded in this grasp of musical form is clear from Langer’s writings.

Inward hearing is the work of the mind that begins with conception of form and ends with their complete presentation [that is, “the structural elements, the harmonic tensions and their resolutions”] in imagined sense experience.81

This grasp of artistic form impregnates and determines the quality of the composer’s “inward hearing.” It is supported by all sorts of symbolic devices: the guidance of printed scores, the specific though minute muscular responses of breath and vocal chords that constitute subvocal singing, perhaps individual tonal memories and other references to experience.82

The first stage in artistic creation, therefore, is entirely immanent, the sudden recognition of the total artistic form in imagined experience. From that moment on the artist’s mind is no longer free to wander irresponsibly. It is under the tutelage of the “commanding form.”

In some sense the “commanding form” is “impersonal,” but as such it is not restrictive but enriching; for in the recognition of this matrix lies all the tendencies of the work.83 Every option in the development of the composition is seen in terms of this whole.

The significance of this grasp of “commanding form” in “inward hearing” can be seen more precisely in the distinction between artistic composition and performance. For both are governed throughout by the demands of the commanding form.

Performance is the completion of a musical work, a logical continuation of the composition, carrying the creation through from thought to physical expression. Obviously, then, the thought must be entirely grasped, if it is to be carried on. Composition and performance are not neatly separable at the stage marked by the finishing of the score: for both spring from the commanding form and are governed throughout by its demands and enticements.84

But the inward hearing of the composer under the aegis of this form stops short of just that determinateness of quality and duration that characterizes actual sensation.

This final imagination of tone itself, as something completely decided by the whole to which it belongs, requires a special symbolic support, a highly articulate bodily gesture: overtly, this gesture is the act of producing the tone, the performer’s expression of it; physiologically, it is the feeling for the tone in the muscles set to produce it.85

Actual performance, though guided by the same commanding form grasped by the composer in inward hearing, is a new creative act; for it demands a decision as to precisely what every tone will “sound like.”

If he is not the composer, then the commanding form is given to him; a variable but usually considerable amount of detail in the development of the form is given; but the final decision of what every tone sounds like rests with him. For at a definite, critical point in the course of musical creation a new feeling sets in, that reinforces the tonal imagination and at the same time is subject to it.86

Langer notes that artistic performance can be very close to symptomatic and emotional “self-expression.” But, she points out, as long as personal feeling is concentrated on and subordinated to the commanding form of the piece, the latter is the very nerve and “drive” of the artist’s work.87 It is similar to the public speaker intent primarily on his meaning, not mode of expression: “rem tene, verba sequuntur.” If, on the other hand, the performer lets his own need for some emotional catharsis make the performance simply his “outlet,” the work will lack intensity because its expressive form will be inarticulate and blurred. Art begins only when a formal factor is recognized as the framework within which the chance attributes of immediate emotion can occur. Similarly, the speaker becomes “oratorical” when lack of attention to meaning results in misplaced emphasis.

The primacy of artistic insight is evident. This insight impregnates the artist’s or performer’s imaginative envisioning of his work—even the “muscular imagination” of its performance. An artist’s hands, supplemented by his familiar instrument, become intuitively responsive to his understanding of the commanding form. No one could possibly figure out, or learn by rote, the exact proper distance on the fingerboard for every possible interval; but conceive the interval clearly and finger will find it precisely.88

Similarly, the perfection of the dance depends upon the conception of a “body-feeling” in which no movement is automatic, but every voluntary muscle, even to the fingertips and eyelids, cooperates in the expression of the rhythm prefigured in the first intentional act.89

5. The “Laws” of Imagination

The distinction between literal and artistic meaning comes to the fore in treating of the literary arts. For here the materials are words and language that tend, in people like Langer and ourselves, toward literal meaning. But such literal meaning characterized by the discursive form of language, by distinctions of A from non-A, cannot grasp the complex life of feeling, or as Langer puts it, the “essential dialectic of feeling.”90

In addition, unlike language, which is a symbolism, a system of conventional symbols, a work of art is a single, indivisible symbol.91 The appreciation of a work of art always begins with a single intuition of its total import, and increases by contemplation as the expressive articulation of the artistic form becomes apparent. Language, on the other hand—discourse—involves the “passage from one intuition, or act of understanding, to another.”92 Finally, the import of a work of art cannot really be paraphrased in discourse. Even an art such as poetry, which evidently involves assertions with literal meaning, defies literal translation.93 For even though the material of poetry is discursive, its significance, or “vital import,” is not. That import is expressed by the poem as a totality and cannot be grasped by a literal paraphrase. All art as such is untranslatable. Langer notes that poetry “translated” into other languages may reveal new possibilities for its skeletal literal ideas and rhetorical devices, but the product is a new poem.

By speaking of feeling as the import of art Langer means the whole of feeling-influenced life, including the life of thought. The distinction between feeling-influenced consciousness and differentiated discursive thought can best be seen in her writings on poetry. For here she explicates what she calls the “laws” of each form of consciousness. The distinction between the two forms becomes clear because in poetry the very materials of the art are expressions of literal consciousness.

For Langer all poetic art, including literature, drama and the film, creates the illusion of “virtual life.” Since its materials are words and statements, the temptation is to ask: “What is the author trying to tell us?” instead of “What has he created?” The product of poetic art, “poesis,” is the appearance of “experiences,” the semblance of events lived and felt. These. events are unified into a simplified whole in which they are much more fully perceived and evaluated than the events of a person’s actual history.94

But just as painting, sculpture, and architecture are different modes of virtual space, literature, drama, and the film are distinct modes of “poesis.” In literature the primary illusion of virtual, entirely experienced, “life,” is in the mode typified by memory. Actual experience is usually ragged and unaccentuated, a welter of sights, sounds and feelings.95 It is only half perceived. Memory, however, functions by selecting and sifting these experiences and giving them a closed distinguishable form and character.

Lyric poetry, for example, brings out the highly perceptible character of these virtual events. The smallest event, the occurrence of a thought or feeling, is presented in such a way that its emotional value is immediately apparent.96 The poetic aspect of the event is given directly in the telling: it is as terrible or as wonderful as it “sounds.”97 The poet creates events in a psychological mode rather than as a piece of “objective” history. It is the mode of “naive experience” in which action and feeling, sensory value and moral value, are still undivorced.98

In a highly original chapter Langer presents the laws and “logic” of imagination which guide literary production.99 The cardinal principle of imagination is what Freud called Darstellbarkeit.100 It refers to the fact that every product of imagination comes to the percipient as a qualitatively direct datum. The emotional import of the datum is perceived as directly and immediately as the datum itself. This is what is referred to when a poetic presentation, even of a speculative thought, is said to have an “emotional quality.”

This principle is responsible for many “illogical” poetic and mythical usages of language.101 Instead of the principle of the excluded middle characteristic of logical thought, poetry often contains what Freud called “over-determination.” Thus, instead of “either A or B,” poetry combines opposites: both love and hate.

In literature there is strictly speaking no negative. The words, “no,” “not,” and so on, create by contrast what they deny: and this creation is an integral part of the literary illusion. Langer refers to Swinburne’s “The Garden of Proserpine,” in which almost every line is a denial:

Then star nor sun shall waken

Nor any change of light:

Nor sound of waters shaken,

Nor any sound or sight:

Nor wintry leaves nor vernal;

Nor days nor things diurnal;

Only the sleep eternal

In an eternal night.

Everything that is denied is thereby created and forms the background for the final two verses.102

Another characteristic of literary and mythical imagination is the tendency for variations on the same theme. Instead of the proof required by logical thinking, mere reiteration is often sufficient to create the semblance of reasoning. (As Lewis Carroll’s Bellman says, “If I say it three times it’s true.”)

Instead of the logical development of one theme, the literary imagination often simultaneously develops many themes. This is Freud’s principle of condensation, and its effect is to heighten the “emotional quality” of the created image and to make one aware of the complexities of feeling.103 Langer quotes Shakespeare:

And Pity, like a naked newborn babe,

Striding the blast, or Heaven’s Cherubim, hors’d

Upon the sightless couriers of the air,

Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye

That tears shall drown the wind.

The literal sense of phrases indicating “that tears shall drown the wind” and that a newborn babe and a mounted guard of cherubim will blow a deed in people’s eyes is negligible. And yet, the poet has created an exciting figure, the created image of complex feelings.

These are some of the principles of literary imagination. The poet creates a total illusion of human experience according to these principles, an experience which thereby becomes emotionally transparent. In lyric poetry the experience is minimal, “the occurrence of a living thought, the sweep of emotion, the intense experience of a mood.”104

The difference between lyric poetry and other literary products is not radical. It is the frequency and importance of certain practices, such as metrical versification, speech in the first person, intense imagery, and so on, that makes lyric poetry a special type of “poesis.”

Other types of literature exploit more powerful techniques of creating the illusion of life in the mode of memory—especially the element of narrative. The “story-interest” in the folk ballad and the medieval “romance” becomes so powerful that the hypnotic powers of rhythmic speech are no longer necessary to maintain the artistic illusion.105 But the difference between poetry and prose fiction is primarily technical, that is, in the materials employed—not in the illusion created. Both use proper techniques to create the semblance of life fully felt. While the medieval “romance” took as its motif the social world in which individuals participated according to their status, the modern novel takes as its pervasive theme the evaluation and hazards of individual personality. Yet, the novel is still the experience of created life and not sociological or psychological theory. Langer notes that it is the particular ‘slant” in which events are recounted—whether in the medieval romance or in the modem novel- that constitutes the “poetic transformation” which transcends the particular materials of character study, psychological insight, and so on.106 In the same way speculative and moral beliefs, all assertion of facts, as used in literature, are not debatable. Their literary value depends entirely on their use to create the semblance of life—its seriousness and difficulty, the sense of strain and progress.107

A word on drama. Though literature and drama are both poetic, creating the illusion of virtual history, drama is not strictly literature. For it does not create virtual events that compose a “Past,” but rather immediate visible responses of human beings oriented toward a virtual “Future.” Certainly, the theater creates a seemingly perpetual present moment; but as Langer points out, it is only a present filled with its own future that is really dramatic. In actual life the impending future is often only vaguely felt; we recognize a distinct situation only when it has reached, or nearly reached, a crisis.108 But in the theater we see the whole set-up of human relationships and conflicting interests long before any abnormal event has occurred that would, in actual life, have brought it into focus. This illusion of a visible future is created in every play; it is the primary illusion of “poesis” in the mode peculiar to drama. While the literary mode is the mode of Memory, the dramatic is the mode of Destiny.

Finally, a word on art criticism. Any attempt of criticism to convey “the meaning” of a work of art, even of literature, is by that very fact an exercise in literal, not aesthetic, symbolism. This is the sense of Langer’s reservation of the term “meaning” to literal symbolism, while she speaks of the “import” of art.109

Artistic expressiveness, unlike literal meaning, cannot be demonstrated. It cannot be pointed out, as the presence of this or that color contrast, balance of shapes, and so on, may be pointed out. For either it is grasped directly and as a whole by one act of aesthetic perception, or it is not grasped at all. “No one can show, let alone prove to us, that a certain vision of human feeling . . . is embodied in the piece.”110

This does not mean, however, that works of art cannot be criticized. Appreciation of the total artistic illusion comes first; but the recognition of how that illusion was made is a product of analysis reached by discursive reasoning.111 The critical judgment of art is guided by the virtual result, the symbolic illusion the artist has created. Particular materials or techniques are neither good nor bad, strong nor weak, but must be judged entirely in terms of the artistic result. That is why criticism can never arrive at criteria of artistic excellence, that is, expressiveness. There can be no rule for artistic success. Langer remarks that although it is possible to show the causes failure in poetry, it is not always possible to explain how a poem has succeeded.

Langer agrees with R. G. Collingwood that candor is the standard between good and bad art. Bad art results from the interference of extraneous emotion with the imagination and expression of feeling; and art thus corrupted at its source, is not true to what candid expression would be.112

Conclusion

What then did Bernard Lonergan learn from Susanne K. Langer? First of all, in Feeling and Form Langer provided Lonergan with the materials concerning the meaning of art that facilitated his own definition of art as the objectification of a purely experiential pattern.

Secondly, even though Lonergan in Insight had written of the aesthetic pattern as the liberation of experience from “the confines of serious-minded biological purpose,” Lonergan learned much more from Langer about the concrete details of this process of liberation, as it takes place in the particular art forms. In each of these aesthetic areas there is a liberation of “the ready-made subject” from his or her “ready-made world.” As he noted at the end of his analysis of art in Method in Theology,

Again, let me stress that I am not attempting to be exhaustive. For an application of the above analysis to different art forms in drawing and painting, statuary and architecture, music and dance, epic, lyric, and dramatic poetry, the reader must go to S. K. Langer, Feeling and Form. The point I am concerned to make is that there exist quite distinct carriers or embodiments of meaning.113

Thirdly, even though in Insight he had written of art as providing “the spontaneous joy of free intellectual creation,” from Feeling and Form Lonergan learned a great deal more about the concrete process of artistic creation and appreciation. In particular, in Insight he footnoted Langer’s analysis of musical creation, the grasp of the commanding form and its articulation in a symphony, a song, and so on. Writing of artistically differentiated consciousness in Method in Theology, he says:

Its higher attainment is creating; it invents commanding forms; works out their implications; conceives and produces their embodiment.114

In words almost out of Langer herself, Lonergan writes:

The process of objectifying involves psychic distance. Where the elemental meaning is just experiencing, its expression involves detachment, distinction, separation from experience. While the smile or frown expresses intersubjectively the feeling as it is felt, artistic composition recollects emotion in tranquility. It is a matter of insight into the elemental meaning, a grasp of the commanding form that has to be expanded, worked out, developed, and the subsequent process of working out, adjusting, correcting, completing the initial insight. There results an idealization of the original experiential pattern. Art is not autobiography. It is not telling one’s tale to the psychiatrist. It is grasping what is or seems significant, of moment, concern, import, to man. It is truer than experience, leaner, more effective, more to the point. It is the central moment with its proper implications, and they unfold without the distortions, interferences, accidental intrusions of the original pattern.115

Another theme that appears in Lonergan’s writings on art after reading Feeling and Form is the theme of the organic character of the feelings associated with the artistic image.

So verse makes information memorable. Decoration makes a surface visible. Patterns achieve, perhaps, a special perceptibility by drawing on organic analogies. The movement is from root through trunk to branches, leaves and flowers. It is repeated with varying variations. Complexity mounts and the multiplicity is organized into a whole.116

In summary, Langer provided for Lonergan a wealth of material, both from her own experience and understanding and from the testimony of other artists and philosophers of art on aesthetic experience and artistic creation.

Finally, we can conclude by noting what Langer might have learned from Lonergan. First of all, she might have learned a more accurate and explanatory account of human interiority that would have set her fine work on art into a wider context.

For example, because of what became evident in her later writings, an inadequate insight into insight, Langer fails, it seems to me, to note the intentional character of human feelings. Not only do our human feelings reflect their organic depths, but they also involve awarenesses of human values: vital, social, cultural, personal, and religious. Consequently, Lonergan can write of our purely experiential, aesthetic, patterns:

To them accrue their retinue of associations, affects, emotions, incipient tendencies. To them also there accrues the experiencing subject with his capacity for wonder, for awe and fascination, with his openness to adventure, daring, goodness, majesty.117

This is what in Insight Lonergan called the operator on the level of our sensitive being: corresponding to the notion of being on the intellectual level. There is, then, in Lonergan there is a wider significance to the theme of art as liberation. For the question can be asked: liberation for what? In A Second Collection he speaks of it as the liberation of the ordinary person’s ordinary experience into the known unknown, the realm of mystery.

There’s imagination as art, which is the subject, doing—in a global fashion—what the philosopher and the religious person and so on do in a more special fashion. It’s moving into the known unknown in a very concrete, felt, way.118

Elsewhere he says:

It is a withdrawal from practical living to explore possibilities of fuller living in a richer world. Just as the mathematician explores the possibilities of what physics can be, so the artist explores possibilities of what life, ordinary life, can be.119

Finally, in Topics in Education Lonergan sets art within its ultimate significance, without which, he says, art can become just play or aestheticism. He refers to Socrates’ indictment in Athens for saying that the moon was just earth and the clouds just water.

Art, whether by an illusion or a fiction or a contrivance, presents the beauty, the splendor, the glory, the majesty, the “plus” that is in things and that drops out when you say that the moon is just earth and the clouds are just water. It draws attention to the fact that the splendor of the world is a cipher, a revelation, an unveiling, the presence of one who is not seen, touched, grasped, put in a genus, distinguished by a difference, yet is present.120

He refers to Saint Augustine:

St. Augustine says in his Confessions that he sought in the stars, and it was not in the stars; in the sun and the moon, and it was not in the sun and the moon; in the earth, the trees, the shrubs, the mountains, the valleys, and it was none of these. Art can be the viewing this world and looking for the something more that this world reveals, and reveals, so to speak, in silent speech, reveals by a presence that cannot be defined or got hold of.121

It seems to me that in Susanne K. Langer’s Feeling and Form Bernard Lonergan grasped in a fuller way what the experience of art could mean.

Notes

1 Susanne Langer, Mind: An Essay on Human Feeling, Vol. I (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1967). Volume II and Volume III published in 1972 and 1982 respectively. Abridged edition of three volumes, 1988.

2 See Richard M. Liddy, Art and Feeling: An Analysis and Critique of the Philosophy of Art of Susanne K Langer (Ann Arbor: University Microfilms, 1970); also, review of Susanne K Langer, Mind: An Essay on Human Feeling, Vol. I, in International Philosophical Quarterly, vol. 10, n.3 (1970) 481-484. [posted on this site.—A.F.]

3 See Frederick E. Crowe, Lonergan (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1992) 50. See also the editorial note in Insight: A Study of Human Understanding, Collected Works of Bernard Lonergan, Vol. 3 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992) 791: “Langer’s work was confirmatory for him of what he had already written.”

4 Insight 208, 567.

5 Bernard Lonergan, Topics in Education, Collected Works of Bernard Lonergan, vol. 10, eds. Robert M. Doran and Frederick E. Crowe (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993) xii-xiii.

6 See “Time and Meaning,” a lecture given to the academic community of Regis College, Toronto, September 16, 1962; published in Bernard Lonergan, 3 Lectures (Montreal: Thomas More Institute Papers, 1975) 36-37, 50-51. References to Langer are scattered throughout Lonergan’s various courses and institutes on method. Among other places see unpublished lecture at Thomas More. Institute, “The Analogy of Meaning,” September 25, 1963, where he also refers to a book published two or three years ago by Rene Huighe, Art and the Soul, L’Art et L’Ame, profusely illustrated and studying the meaning in pictorial art.”

7 Bernard Lonergan, Method in Theology (New York: Herder and Herder, 1972) 61. In his lectures on education he says: “I propose to reflect on a definition of art that I thought was helpful. It was worked out by Susanne Langer in her book, Feeling and Form. She conceives art as an objectification of a purely experiential pattern. If we consider the words one by one, we will have some apprehension of what art is, and through art an apprehension of concrete living.” Topics in Education, 211. In his 1962 lecture on “Time and Meaning” he says that he is following Susanne Langer’s Feeling and Form, “which I found very illuminating on the nature of art.” (3 Lectures, 36).

8 Feeling and Form 40; 60; Susanne K. Langer, Problems of Art (New York: Scribner, 1953) 63; other definitions can be found in my doctoral dissertation, Richard M. Liddy, Art and Feeling 31-32.

9 Insight, 22 (xxviii); our first reference is to the collected work edition, the second to the prior editions.

10 Insight 14 (xx).

11 Insight 207-208 (184).

12 Insight 208 (185).

13 Topics in Education 209.

14 A Second Collection 224.

15 See Langer’s obituary in the New York Times, July 19, 1985, 12.

16 Langer, Problems of Art 125. Also, Susanne K. Langer, Philosophy in a New Key (New York: New American Library, 1948) 78-82.

17 On Cassirer’s influence on Langer, see Art and Feeling 20-24.

18 Langer, Philosophy in a New Key 83-86.

19 In Feeling and Form Langer makes a distinction between the meaning of literal discursive symbolism and the “import” of art. See 31-32.

20 Langer, Philosophy in a New Key 61-70.

21 Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 4.0141, 39. Lonergan refers to this example in Topics in Education 211.

22 Langer, Philosophy in a New Key 84.

23 Topics in Education 212.

24 Langer, Philosophy in a New Key 178.

25 Langer, Feeling and Form 18.

26 Langer, Feeling and Form 22. The use of the term “reality” with its metaphysical overtones is studiously avoided by Langer.

27 Langer, Feeling and Form 45, 50. See Topics in Education, 216.

28 Liddy, Problems of Art 32.

29 Langer, Feeling and Form 29.

30 Liddy, Problems of Art 27.

31 Quoted from Roger Fry, Vision and Design, in Philosophy in a New Key, 238. Lonergan usually illustrates this characteristic of art through his standard example of waiting for a stop light: “The significance of art is a liberation from all the mechanizations of sensibility. The red and green are signals that let you take your foot off the brake and put it on the accelerator. There’s the routinization of sensibility—the ready-made man and the ready made world, with set reactions responding to stimuli—and art liberates sensitivity, allows it to flow in its own channel and with its own resonance.” A Second Collection 224.

32 Feeling and Form 30.

33 Feeling and Form 397.

34 Feeling and Form 50-51.

35 See Problems of Art (New York: Scribners, 1957)28.

36 See Problems of Art 127: “One does not see a picture as a piece of spotted canvas, any more than one sees a screen with shadows on it in a movie.”

37 Feeling and Form 50; see 48.

38 Problems of Art 81-32.

39 Topics in Education 216.

40 See Philosophical Sketches (New York: New American Library; 1964) 76: “I say ‘perceptible’ rather than ‘sensuous” forms because some works of art are given to imagination rather than to the outward senses. A novel, for instance, usually is read silently with the eye, but is not made for vision, as a painting is; and though sound plays a vital part in poetry, words even in poetry are not essentially sonorous structures like music. Dance requires to be seen, but its appeal is to deeper centers of sensation. The difference between dance and mobile sculpture makes this immediately apparent. But all works of art are purely perceptible forms.”

41 See Feeling and Form 49-50.

42 See Feeling and Form 69ff.

43 Feeling and Form 73.

44 Problems of Art, 28. Because it depends on a completely different, “liberated,” orientation of consciousness, the virtual space of the visual arts cannot even be said to be “divided” from “actual common sense space, but is entirely self-contained and independent. See Feeling and Form 72ff.