AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

.jpg)

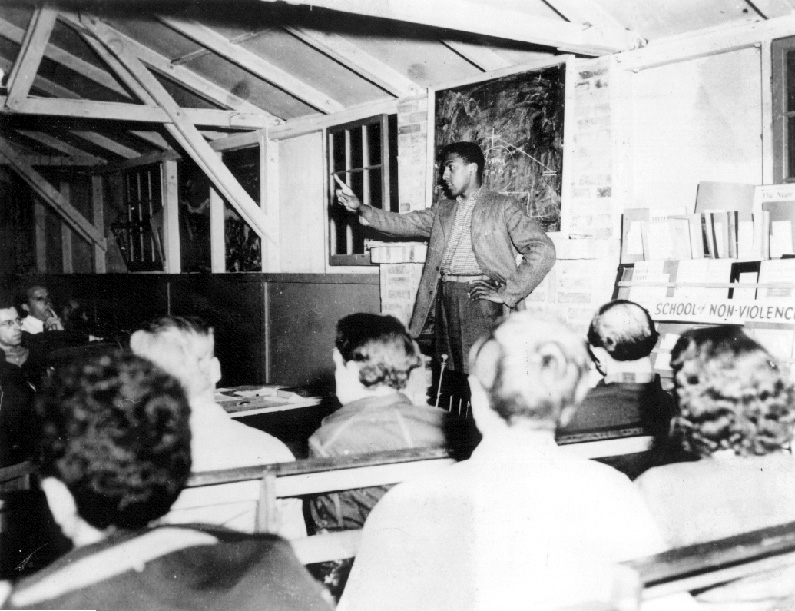

Bayard Rustin advising conscientious objectors, Powellsville, MD, 1943

[UPI/Corbis-Bettmann]

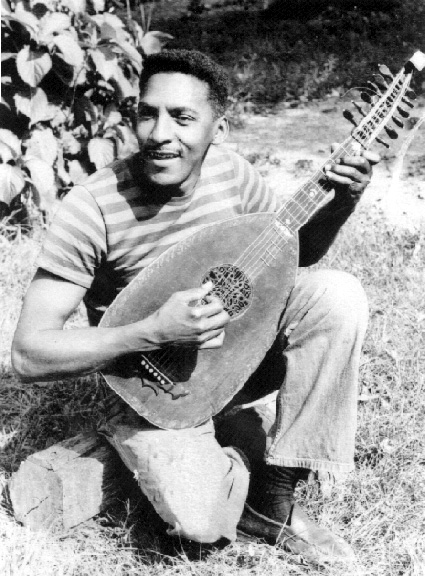

Playing lute, late '40s

[Estate of Bayard Rustin]

With Malcolm X, 1960

[Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Archives]

With Martin Luther King, March on Washington, August 28, 1963

[Bill Scott]

Speaking at March on Washington, August 28, 1963

[UPI/Corbis-Bettmann]

Trafalgar Square, 1983

[Walter Naegle]

Review of Jervis Anderson, Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen, A Biography. Harper Collins. From Virginia Quarterly Review, Winter 1998, 185-190.

Posted May 27, 2008

A Quaker Activist

Hugh Murray

Jervis Anderson’s biography of Bayard Rustin reveals that the restricted opportunities for gays did not always result in constricted lives. Individuals like Rustin overcame those barriers to lead productive lives while contributing to the enhancement of the entire nation. Rustin is best known as the organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, at which a quarter of a million assembled, black and white, male and female, and heard Rev. Martin Luther King enunciate his “dream” of a time when his children would be judged by their character and not by the color of their skin. That March had major political consequences—pressuring Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Born in 1912 in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Rustin excelled in high school at track, academics, public speaking, and music. He received a scholarship to a black religious college and sang (well enough to be a professional) in a quartette to help raise funds for the school. He was expelled his second year, however. Anderson reports the rumored reason for his dismissal was that Rustin had fallen in love with the son of the college’s president. Shortly thereafter, Rustin ended his studies at Cheney State Teachers College, again because of “something naughty.”

Bayard’s family had ties both to the African Methodist Episcopal and the Quaker churches. In the 1930’s, with war looming in Europe, Rustin veered toward his Quaker pacifism. After the Hitler-Stalin Pact, the American Communist Party strongly opposed American involvement in the war, especially on the side of the imperialist powers, Britain, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Rustin was then a member of the Young Communist League and enrolled at New York’s CCNY, a center of intellectual political debate. For the YCL Rustin was asked to lead a campaign against segregation in the U.S. armed services, then vastly expanding because of the newly instituted draft. He was preparing this campaign when Hitler attacked the Soviet Union. Immediately, the American Communists reversed themselves, and urged American participation in the war against fascism. Rustin was ordered to halt his campaign against the U.S. services. Rustin then quit the Communist Party.

In 1941 Rustin made contact with A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Workers, the only black union in the AFL. Randolph, a long-time black activist, had also felt betrayed by Communist tactics of reversal when he headed the National Negro Congress in 1939.

Rustin’s pacifism now led him to the Fellowship of Reconciliation [FOR], a small, slightly religious pacifist group headed by Rev. A. J. Muste. Also in FOR was the youthful James Farmer, who induced FOR to subsidize a new, pacifist organization to combat racism, the Congress of Racial Equality [CORE]. Farmer and Rustin were the most prominent black spokesmen for pacifism in FOR, and both sought to create new, non-violent methods to overturn racist practices.

In 1943 Rustin chose to abandon his status as a religious conscientious objector; yet, he refused to be drafted. Consequently, in 1944 he was sentenced to three years in prison. Released in June 1946, Rustin resumed work for FOR. In 1947, following a Supreme Court decision invalidating segregation in interstate travel, FOR organized the first “freedom ride,” the Journey of Reconciliation of 1947. Though the NAACP’s Thurgood Marshall discouraged the venture, Rustin was among the integrated teams on the Greyhound and Trailways buses, and among those arrested for integrating facilities. When the North Carolina NAACP refused to appeal their cases, Rustin had to spend 30 days on a chain gang for that crime.

Rustin, a skillful orator and a stirring singer, was a powerful spokesman for FOR, and travelled to Europe, Africa, and India to promote the cause. In India, the principles of Gandhi’s non-violent resistance had been implemented to liberate the nation from British rule, and Rustin met prominent figures there. He also met blacks who were about to assume leadership of their new nations during the twilight of imperialism and the dawn of independence. Indeed, Rustin was offered and accepted a post with Nigeria’s Nnandi Azidkiwe as soon as he completed one more speaking tour in the U.S. for FOR.

But during that tour, in January 1953, Rustin was arrested in Pasadena, California on a “morals charge.” He had been caught by police in a parked car having sex with two men. Rustin now had to endure a prison sentence, not for the cause of peace, or the cause of ending racism, but for what was then a shameful crime. When released, FOR essentially fired him and gave him almost no severance pay after eight years’ employment. Other job offers evaporated. Rustin wondered if Muste now wanted him to become a shoeshine man. Rustin endured low-status jobs, humiliation, unemployment, and therapy sessions—not an easy “sentence” for a proud man in his 40’s who had been groomed to become an American Gandhi. Happily, there was another small, but less religious, pacifist organization, the War Resisters League, and after some months, it hired Rustin. But for Rustin, those were terribly long months.

Then in December 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, the bus boycott began, and WRL sought to keep it on track as a nonviolent protest. With prodding from Lillian Smith and FOR, in February 1956 Rustin was dispatched to aid Rev. King advising him on matters of symbol and substance. For example, segregationists had bombed King’s home. When Bayard arrived, he noticed King had a rifle in the living room, and he urged King to remove it. If his followers were to remain non-violent in the face of hatred and provocation, so must King. Indeed, King could not afford to have a weapon, for his enemies would contend that he started the violence. Acceding to Rustin’s reasoning, King removed the rifle.

Rustin also urged King to create an organization to advance other such peaceful protest campaigns, and the Southern Christian Leadership Council was formed. However, Rustin was deemed suspect by various SCLC ministers—men who disdained a former Communist recently arrested on a morals violation. But King found Rustin’s advice profound and essential, and Rustin headed the Harlem office of the SCLC. In May 1957 Rustin organized the SCLC’s Prayer Pilgrimage to Washington in which 30,000 partook, and he also organized other marchers and boycotts in the late 1950’s.

In 1960 Rustin was planning SCLC protests for both the Democratic and Republican conventions of 1960, but Harlem Congressman Adam Clayton Powell objected to the protests aimed at the Democrats. Powell threatened King privately, saying he would start a rumor that Rustin and King were lovers if Rustin were not fired. For the good of the movement, King asked Rustin to resign. Because of the threatened gay charge, Rustin was effectively exiled from the Civil Rights Movement at a time when non-violent direct action was being most widely applied throughout the land.

Rustin had demonstrated too many talents to be crushed by Powell’s blackmail. The WRL assigned him to new projects with anti-nuclear marches in Britain and Africa, where he remained a prominent spokesman of peaceful protest. In 1963, when Randolph began to propose his old dream of a March on Washington, he sought Rustin to coordinate it. This time, the other civil rights leaders agreed, and Rustin did coordinate that massive project. Anderson is at his best in the chapter on the march. Having seen so many film clips of the event, one is tempted to skip the chapter, but the author recreates its electricity. He describes the in-fighting, the disputed speech of SNCC leader John Lewis, the criticism of Rustin’s past; as well as the carping from outside, by Southern segregationists and Malcolm X. But Rustin arranged to have a quarter of a million come to Washington and leave on the same day in a demonstration of determination, topped by the rhetoric of King. And despite the fears and warnings, the demonstration was peaceful.

Rustin then renewed his contacts with King and helped plan the itinerary and accompanied the SCLC leader on his trip to Europe to accept the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

Rustin was the only major civil rights leader without an organization, and one was created for him. The A. Philip Randolph Institute began in the spring of 1965, with Rustin as its director. The institute was funded by organized labor, and for a change, Rustin received a middle-class salary.

But in the mid-60’s new issues rose that were to divide the civil rights movement, and alienate Rustin from both it and the peace movement. Black Power, a slogan used by Stokely Carmichael during a march in Mississippi, was opposed by King, Rustin, and the more established civil rights leaders. Rustin for decades had urged an alliance of labor, peace, civil rights, and religious groups to push a liberal agenda. But younger activists were becoming disillusioned with the liberal leadership. At the 1964 Democratic Convention, Rustin, like most liberals, advised the Mississippi Freedom Democrats to accept a compromise offered by President Johnson, seating two of their delegation, while retaining most of the all-white segregationist, official Mississippi group. The militants viewed this “compromise” as betrayal.

Similarly, on the ever-increasing numbers of Americans being sent to Vietnam, the peace movement became ever more strident in its demands that America pull out. Rustin, long-time spokesman for pacifism, argued that a pull-out would result in a Communist victory. He, Vice President Humphrey, and other liberals, demanded peace talks instead. To the growing, militant peace movement, Rustin’s defense of the Democrats seemed like a sell-out and a betrayal of peace.

In the late 1960’s Black Power advocates demanded, and often got universities to establish Black Studies Departments. Rustin denounced these fields as symbolic, separatist, and an attempt to politicize academia. He warned that blacks who majored in such programs were choosing the wrong majors: they should be competing in math, science, business, and other traditional fields instead.

Under President Nixon a quota system of hiring and promotion, called affirmative action, was instituted and expanded. Rustin openly denounced any such system based on ratios or proportional hiring by race.

The radical of the 1940’s, 1950’s, and early 1960’s, began to look ever more conservative after 1965. To some, the reason was clear—he had sold out. But ever since 1941 Rustin had been suspicious of communism. Though he may have worked with some Communists in King’s entourage, like Jack O’Dell and King’s influential advisor (and former and possible secret Communist) Stanley Levison, Rustin, like Randolph, had been burned by the party. Thus, they were much more likely to criticize the American anti-war movement of the 60’s whose pull-out position they believed would result in a Communist Vietnam. Rustin also criticized King’s address at the Riverside Church of 1967 at which King blamed the continuance of the war on American policy.

Similarly, Rustin had been involved in integrated groups since the 1940’s. His friends and milieu were not examples of black (or white) power, but of integration. And he believed that integration, through non-violent means, would heal the nation. He appealed to blacks and whites to join civil rights protests, to join the March on Washington, to pass civil rights legislation. So how could he endorse quotas and affirmative action if it would discriminate against whites?

Later he did revise his antagonism to Black Studies, seeing it as a legitimate field of study. But he also noted there were charlatans in the field.

Rustin also split from the radicals on Middle-Eastern issues. Whereas they generally supported the oppressed, dark-skinned Palestinians, he supported Israel, the only democracy in the area, founded as a haven for the Jewish victims of anti-Semitism.

Rustin continued to win various awards in the 1970’s, but he was no longer a radical. Like his associates among the anti-Communist social democrats, Rustin was more akin to those who would be labeled neo-conservatives. By the 1970’s his gayness was no longer an issue. In 1972 he was arrested for carrying a concealed weapon, an antique cane that sheathed a sword. But in an era of rising crime, Anderson does not report that Rustin was mugged.

After a ruptured appendix was misdiagnosed and mistreated, Rustin died in 1987.

Anderson’s book is a good read, but there are some questionable judgments. He states that Wilson Record’s Cold-War study, The Negro and the Communist Party, is the definitive work on blacks and Communists! Indeed, one of the gaps in this biography concerns when Rustin joined the YCL, and who were his associates at the time. The possibility that Stan Levison was one is surely intriguing. While Anderson interviewed many social democrats, he seems to have ignored those who might have been Communists when Rustin was a member.

A fuller discussion of Rustin’s critique of Black Studies and quota hiring, though politically incorrect, may have given the reader more appreciation of Rustin’s intellect and dissent. Moreover, there were charges that Max Schachtman and the international wing of the AFL-CIO had worked closely with the CIA since the 1950’s. As Rustin grew closer to Schachtman and the AFL-CIO, and as Rustin remained an influential spokesman on foreign affairs while he roved the world, one should have asked about possible links between Rustin and the CIA. Anderson avoids the topic. He notes in a few sentences that Rustin had a steady companion for a decade, William Naegle, but says nothing more about the relationship or even who Naegle was.

Anderson wrongly states that a FOR-launched group, the Americans for South African Resistance, was “the first organized effort in the United States on behalf of any African freedom movement.” Had he not heard of Paul Robeson’s Council of African Affairs? Or even the NAACP? Or the many groups that organized to aid Ethiopia when Mussolini’s armies invaded in 1935?

Despite my quibbles, Anderson has written a fine biography of the courageous man, Bayard Rustin.