AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

.jpg)

The American Historical Review, Vol. 107, No. 1, February 2002. Exactly six years earlier, Murray had another, shorter letter on Scottsboro in the same journal, posted elsewhere on this site.

"Had today’s feminists laws been in force in the 1930s, there might have been a European tour for Ada Wright in 1932, but her sons would have been electrocuted in 1933 and the general public would have applauded their executions."

Hugh Murray

To the Editor:

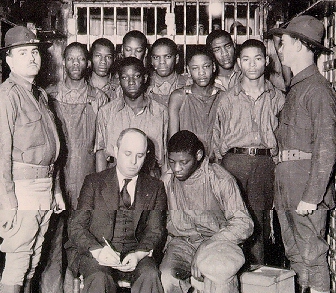

In “Mother Ada Wright and the International Campaign to Free the Scottsboro Boys, 1931–1934” [106:2, April 2001] James A. Miller et al. note that neither of the two standard histories of the case “pursues the international defense campaign” (p. 388, n. 1). Not quite. Dan Carter confidently believed he knew enough about that campaign to write, “Nowhere was the subservience of the [Scottsboro] boys’ interest to Party goals more evident than in the European tour of Mrs. Wright” (Dan T. Carter, Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South, 1969, 171–72). Clearly, the material amassed by Miller et al. demonstrates that Carter’s words were little more than ignorance seasoned with Cold War prejudice.

On March 20, 1976, at the New School for Social Research, I presented a paper at a conference sponsored by the Union of Radical Political Economists on Mrs. Wright’s tour. I began by challenging Carter’s interpretation of her campaign, but nevertheless arrived at a conclusion quite different from that offered in the recent AHR article. While Miller et al. present a popular effort with Ada Wright winning friends beyond the party, and occasionally this was surely true, I discovered the other side of the coin. Indeed, I found so little genuine support that I titled my paper, “Crusade from Above.” My conclusions were, first, Communists attempted to create concern in Europe for the fate of the convicted Scottsboro youths, often at great expense of energy and space in their newspapers, and often with little popular response; second, it is possible that European Communist parties actually subordinated their own interests, narrowly viewed, to the cause of the Scottsboro boys; and, third, Mrs. Wright’s tour increased the intensity of Scottsboro protest as she informed Europeans of American injustice toward blacks.

I cannot detail here the research that led me to those conclusions (see my unpublished article in the Hugh Murray Papers at Tulane University Library), so one example must suffice. On June 23, 1931, the London Daily Worker headlined, “Demand for Release of Negro Workers; Tower Hill Demonstration to American Embassy.” But a careful reading of the article about the Sunday rally shows, “The mass demonstration . . . to protest against the Labour Government’s employment policy passed a resolution” regarding Scottsboro (emphasis mine). Furthermore, the London DW’s story about the same rally, published on June 22, had read, “3,000 at Tower Hill Demonstrate to Fight ‘Abuses’ Attack.” In a description of the same demonstration, Scottsboro was deemed so inconsequential that it went unmentioned. The London DW by the next day was clearly attempting to magnify the British support for the Scottsboro campaign.

In the British International Labour Defence’s pamphlet, Stop Legal Lynching of Nine Negro Boys (1931), it urged, “In every working-class organisation, trade union branch, co-operative guild, political party, etc., resolutions demanding their release, and donations for their defence should be passed.” I do not have space to record each article in the London DW announcing this or that organization’s Scottsboro resolutions. But these resolutions evidence more the party leadership’s resolve than enthusiasm by the populace. Even Miller et al. concede the disappointment of Comrade Arnold Ward when, observing the 1932 London May Day rally with 50,000 participants, he counted a mere five blacks (p. 424). Despite the continual promotion of the Scottsboro case by the DW and the CP, the general lack of support should be kept in mind when reading a DW article of June 1, 1932:

“When we have a trade union branch under our influence we do not always work the branch in a way to increase our influence throughout the union . . . Very often the questions we raise are not the questions which are interesting the workers, but the questions which we think ought to interest the workers.”

As to why the Communist leadership was so determined to create a cause célèbre of Scottsboro, one must not overlook Stephen Koch’s view that the “idea” of America was the great alternative to the Soviet ideal. By promoting the Sacco-Vanzetti and Scottsboro cases, depicting American oppression of immigrants and minorities, the Stalinist state might appear more acceptable (Koch, Double Lives, 1994, esp. 30–44).

Next, the question of methodology. I had no access to the Soviet material discussed in the Miller article. But how heavily should one rely on assessments in Soviet archives to arrive at reality? If comrades were reporting to Moscow on how popular the Scottsboro case was, it may have been true—or it may have been telling the boss what he wants to hear. For example, when viewing the picture of the large gathering of the Internationale Arbeiter Hilfe in the Miller article (p. 417), one can wonder, how committed was each delegate to the cause of Scottsboro? Or was Scottsboro one more issue tacked on by the leadership of the IAH, as at the Tower Hill Demonstration in London?

Finally, there is the question of omissions in the Miller article. They mention Paul Robeson (p. 428) but fail to add that, a few years after Ada Wright’s tour, Robeson co-chaired a Scottsboro Defence Committee in Britain alongside Johnstone (Jomo) Kenyatta. I have elsewhere described the changes in American popular culture as reflected in the treatment of the Scottsboro case from the 1930s to 1970 (“Changing America and the Changing Image of Scottsboro,” Phylon, March 1977).

However, another movement has since influenced Americans view of Scottsboro. In 1975, Susan Brownmiller began her attack in her influential volume, Against Our Will, and the feminists soon succeeded in enacting sexual harassment and rape-shield regulations. What recent historians fail to point out, and this is most important, if feminist-sponsored rape-shield laws had been in effect in Alabama in the 1930s, there would have been no way for Attorney Leibowitz to introduce into court the sexual background of the women, no way for him to expose the lies they had concocted, no way to reveal to the world the innocence of the accused boys!

Had today’s feminists laws been in force in the 1930s, there might have been a European tour for Ada Wright in 1932, but her sons would have been electrocuted in 1933 and the general public would have applauded their executions. The silence of recent historians on this point amounts to political correctness, cowardice, or both.

Hugh Murray

Milwaukee, WI

The authors of the article decline to reply.