AnthonyFlood.com

Philosophy against Misosophy

.jpg)

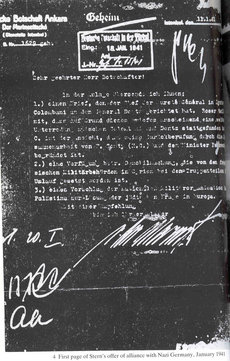

Stern Gang asks Nazis for alliance, January 1941. Scanned from Joseph Heller, The Stern Gang: Ideology, Politics, and Terror 1940-1949. Heller is Professor Emeritus at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Review of Francis R. Nicosia, The Third Reich and the Palestine Question. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985. From New German Critique, Number 42, Fall 1987, 176-180. A fascinating look at history’s two most famous national socialist movements and their coincidence of interests. The editor told Murray it was the best essay he'd seen on the subject, but he saw it only after more than a dozen other editors rejected it. It lives on here.

I provided the title to this previously untitled review.

Anthony Flood

February 20, 2007

The Zionist-Nazi Connection

Hugh Murray

Many readers will be shocked by the contents of this well-researched book, for it holds many surprises. Georg Kareski, Revisionist Zionist, interviewed in Dr. Goebbels’ newspaper, endorsed the Nazi’s racist Nuremberg law of 1935 (p. 56). Kurt Blumenfeld, chairman of the main German Zionist group, the ZVfD (Zionistische Vereinigung für Deutschland), noted in April 1933, shortly after Hitler came to power, “. . . there exists today a unique opportunity to win over the Jews of Germany for the Zionist idea.” A few months later, the ZVfD sent a memorandum to Hitler:

Zionism believes that the rebirth of the national life of a people, which is now occurring in Germany through its emphasis on its Christian and national character, must also come about among the Jewish people. For the Jewish people, too, national origin, religion, common destiny and a sense of its uniqueness must be of decisive importance to its existence. This demands the elimination of the egotistical individualism of the liberal era, and its replacement with a sense of community and collective responsibility. (p. 42)

Not only did Zionists share a völkisch ideology with the Nazis, they received aid from the Gestapo. Dr. Hans Friendenthal, a former chairman of the ZVfD acknowledged in a 1957 interview: “The Gestapo did everything in those days to promote emigration, particularly to Palestine. We often received their help when we required anything from other authorities regarding preparations for emigration. This position remained constant and uniform the entire time, until the year 1938” (p. 57). The most glaring example of Nazi-Zionist cooperation was the Haavara Transfer Agreement, whereby emigrating Jews could receive some of their blocked German assets in the form of German imports to the Middle East. This agreement continued with minor alteration from 1933 until December 1939. There were other examples of cooperation. Within Germany, the authorities favored Zionist Jewish organizations as opposed to the assimilationist Jewish groups: Zionists could publish, propagandize, wear uniforms, and display the blue and white flag which one day would be that of Israel (but Jews in Germany could not display the German flag). Zionists conducted retraining schools throughout Germany so Jews could learn the skills necessary for resettlement in Palestine. While most Jews had difficulty getting passports to enter Germany, Zionists working with the retraining centers were given priority. German Zionists were encouraged to attend World Zionist Congresses and did so throughout the 1930s. Apparently, the Gestapo even gave weapons to the Hagana in 1937 for use against the Arabs in Palestine.

What did the Nazis get in return?

In 1933, Hitler wanted to get the Jews out of Germany. By 1939, he wanted them out of a Europe that Germany would dominate. Most of Germany’s 600,000 Jews were assimilationist in 1932. Some thought Hitler would not last; others, that “it would not be too bad.” Still others, even if they wanted to emigrate, preferred nearby European countries where they may have had relatives. The United States had a narrow quota discouraging immigration. Because of Germany’s poor economy, even during the Weimar era, legislation restricted the amount of money that a departing émigré could take. In the depression-ridden 1930s, few nations wanted boatloads of immigrants; fewer wanted Jews shorn of assets. Yet, Hitler wanted the Jews out of Germany, and one outlet was Palestine, where Britain had promised to provide a Jewish Homeland in the 1917 Balfour Declaration. The Haavara Agreement allowed emigrating German Jews to retain some of their assets, thereby encouraging them to go to Palestine. The Nazis subsidized German exports to the Middle East with the blocked German-Jewish funds. Beginning in 1933 there was a world-wide attempt to boycott German goods because of its racist and oppressive policies. Jewish groups, unions, and Left-wing organizations supported the boycott. But simultaneously, German goods were entering Palestine and being sold through a Zionist concern. When the issue of boycott arose at World Zionist Congresses of the 1930s, the German delegates opposed it, and the Zionist Congresses rejected it. Among the observers at the 1937 Zionist Congress was Adolf Eichmann. Thus, in working to rid Germany of its Jews and get them to Palestine, the Nazis and the Zionists frequently had common interests and worked together. Interestingly, the German Consul in Jerusalem, Heinrich Wolff, was an ardent Zionist whose wife was Jewish. He believed Zionism was a way to reconcile Nazis and Jews. By the mid 1930s, he was dismissed from his post.

The Nazi-Zionist connection was debated in Germany as a consequence of the Arab uprisings in Palestine beginning in 1936. The Nazis had rejected earlier Arab requests for support because of Nazi racial contempt for the Semitic Arabs, and because Hitler did not want to disrupt his moves for an alliance with Britain. Hitler would not interfere with the British Empire, and, he hoped, Britain would not interfere with Germany’s drive in Europe. By 1937, there were elements in Germany who sought to pester Britain by encouraging the Arabs; and they sought to scrap the Haavara Agreement linking German exports to Zionists in the Middle East. Most important, these Germans were worried by the recommendations of the Peel Commission of 1937—a proposal for separate Arab and Jewish states in Palestine. Most Nazis believed an independent Jewish state would be hostile to Germany and a seat of the international Jewish conspiracy, similar to the Vatican or Moscow. But despite these arguments, Hitler was unwilling to alter his basic policy. As he declared in Mein Kampf, he was unwilling to link the fate of Germany to racially inferior “oppressed nations,” like the Arabs. And he was convinced a racially pure Germany would be a stronger Germany. In 1937, alarm that Jewish emigration was declining (in part because of fighting in Palestine and also because of the German Prosperity bought on by the Nazis), brought proposals to unite emigration in one department, but the basic policy continued and was reaffirmed by Hitler in January 1938. Indeed, in February 1938 Hider empowered a leader of the ZVfD to negotiate in London with the British regarding more Jews entering Palestine.

At the end of 1937, there were still 350,000 Jews left in Germany and on April 1, 1938 some 40,000 Jewish enterprises. Hitler sought a Jew-free Germany. Numbers of refugees were growing, and President Roosevelt called for a conference which met at Evian, France, in July 1938. However, most nations, even the U.S., were unwilling to increase their quotas, and some sought to reduce the number of Jews that could enter their territories. Meanwhile, Germany annexed Austria, and suddenly had many more Jews to dispose of. A new implementation of an old policy began when Adolf Eichmann of the SS entered Vienna. In effect, Jewish property was confiscated, and Jews were quickly issued papers for departure to other countries. Sometimes the papers were false. Meanwhile, the British had acceded to Arab demands and reduced the number of Jewish immigrants permitted to enter Palestine. But the SS, in conjunction with Zionists, was deporting Jews to Palestine both legally and illegally. In November 1938, Kristallnacht shattered the Jewish community remaining in Germany. Eichmann and the SS helped Zionists to gain release from jail and restore their organizations so they could get Jews to Palestine.

Nicosia tells a fascinating story. Tragedy and blood is hidden between the lines, but it is there. He does not allow the present Palestine question to intrude in his story of the 1930s. The reader does not know if he is a Zionist, or favors the P.L.O., and such objectivity is major asset in a work like this.

Nicosia could have included more, especially on the Reich’s policy during the war. What happened to the pro-Axis Iraqi government? What happened to the 2,000 Palestine Germans during the war? What did the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem do? If by 1948 the Hagana got 100,000 illegal Jews to Palestine, how many of them came during the war? With collaboration of the Reich? The book is silent on this. Despite his tide, Nicosia’s book really ends with the war’s beginning in 1939.

The charts at the end of the book are interesting, but one is in German, and a short chronology of pertinent events is lacking. Though there is a chart on legal immigration of Jews into Palestine, it would have been an interesting contrast to note countries of destination other than Palestine.

I detect only one serious error in the book, when the author asserts that “Germany could not have a decisive impact on the level of Jewish immigration to Palestine. . .” (p. 127). But of course, Germany did have such an impact in the 1930s with its persecution which thereby promoted immigration in Palestine, and in the 1940s with its extermination of potential immigrants.

The book notes that the anti-Semitic governments of Poland and Rumania also encouraged Zionism in the 1930s. Apparently, Poland trained the militant Revisionist Zionist Irgun and supplied it with weapons. Nicosia discusses the Madagascan, Ecuadorian, and other proposals current in the late 1930s for the resettlement to Europe’s Jews. The “final solution” is not detailed here, but one can see it as a logical conclusion to Hitler’s racism, Nazi expansion, and war, which blocked his desire to expel Jews from Europe.

Reading Nicosia’s work, one questions how the Zionists could have collaborated with the Nazis, praised the Nuremberg laws, seen Hitler as an opportunity, and rejected the boycott of Nazi-Germany. But the other equally important question also arises: how could they not have?

The Nazi-Zionist collaboration legally brought 50,000 Jews out of Germany to Palestine in the 1930s with assets worth more than 100,000,000 RM. Many of the emigrants had been retrained in Germany for a new life in the Middle East, and many would have been killed by the Nazis in the 1940s, had there been no Nazi-Zionist connection in the 1930s.

The Zionists saved more than 50,000 Jews by getting them out of Europe. Had they fled Germany in 1933 to Austria, Czechoslovakia, France, etc., they would not have gone far enough to be saved. The Left attacked the Zionists for refusing to boycott Germany and generally for collaborating with the Nazis. But how many Jews did the Left save? How many did the U.S.A.?

One can view the problem in another light. The Nazis sought to “purify” Germany by eliminating many elements. Jews had Zionism as an alternative—and by the mid 1930s most young German Jews were Zionists. But there was no gay Zion. There was no Jehovah’s Witness Zion. There was no gypsy Zion. When the Nazis sought to destroy them, these minorities may have been at a disadvantage because they had no equivalent to the Zionist movement. There was a Communist Zion, but the Communist movement was assimilationist. The Soviet Party did not encourage German party members to flee to the USSR. “After Hitler, us,” the German Party boasted. Yet, despite the partial truth of that boast, how many German Communists survived the Reich to repeat the toast in East Germany?

Booker T. Washington urged his followers to “cast down your bucket where you are.” He was willing to accept inferior status to build a base in the homeland. But the Nazis rejected Jews in Germany both as equals and as inferiors. Hitler wanted them out of Germany and a German-dominated Europe. Only the Zionists shared his desire to rid Europe of its Jews. There was cooperation between the two movements, and consequent bitterness between Zionist and the Left-wing Jews, the assimilationist Jews, the pro-boycott Jews. But who saved more Jews?

According to the Left, Zionists were racists, and had collaborated with Hitler. In Nicosia’s book, this is documented. It is unpleasant. Yet it may have been the most effective way of saving Jewish lives. Many Zionists may not like certain features of the book. Yet, after reading it, one can only reflect that it is fortunate that some German Jews did choose the Zionist alternative. Indeed, perhaps more would have survived had they been aligned with Zionism.

Hitler declared that to remove the Jews from Germany, he would cooperate even with the Devil (p. 22). To save some Jews in this removal, the Zionists were just as willing to cooperate with the Devil. The Left condemns the Zionists, even though at another stage the Left was also willing to cooperate. The Zionists can point to a limited success in saving lives of at least 50,000 potential victims. The Left was often just as heroic (perhaps more so) as the Zionists. Yet, how many Jews did the Left save? Perhaps use of a multiplicity of alternatives, often contradictory, is the best way to ensure survival.

Palestine is still a burning issue. There is something to support all sides in Nicosia’s book. But more, there is something for all to reflect upon.