AnthonyFlood.com

Panentheism. Revisionism. Anarchocapitalism.

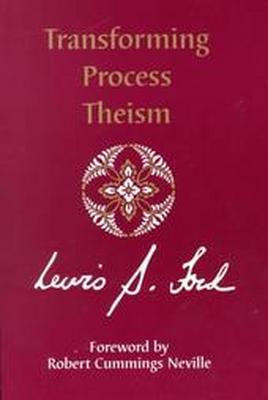

From Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association, Vol. 44, Philosophy and Christian Theology, 1970. Section III: Process Philosophy, 130-140. A substantial portion of this paper consists of “responses which [Lewis S.] Ford wrote to the penultimate draft of this paper, followed by my own ad hoc comments on his responses.” See also Lewis S. Ford’s “The Viability of Whitehead’s God for Christian Theology” and Neville's “Lewis S. Ford’s Theology: A Critical Appreciation” elsewhere on this site.

The Impossibility of Whitehead’s Godin Christian Theologycommenting on the responses ofLewis S. Ford

There are two reasons to consider Whitehead’s conception of God the most important philosophical idea for contemporary theology. First, it is an intimate part of a general philosophical system that, better than any other, restores cosmology to its rightful place in our intellectual concerns; I would say Whitehead’s system is to be accepted in the main, and if his conception of God is mistaken we are obliged to remove it from his philosophy with great care. Second, and more important, Whitehead’s conception of God forces us to reconsider our religious experience, assaying again which elements are basic and which merely appear basic because of the commitments of some interpretive scheme. In a world society where one tradition’s experience must contest with the experience of alien cultures, nothing could be more important for theology.

I will also go on record that Professor Ford’s interpretation of Whitehead’s God is the most sophisticated and plausible of any I have studied. His emphasis on the primordial nature of God as creator of the metaphysical principles rescues Whitehead’s conception from the usual charge of neglecting divine eternity and transcendence. Although I shall argue against Ford on this point, I believe it is at the heart of the issue of the viability of Whitehead’s God.

My attack will begin with Ford’s theme, that Whitehead’s uniqueness lies in separating God from creativity. Then I shall consider arguments concerning (1) human freedom, (2) the intrinsic significance of finite beings, (3) evil, (4) the creation of the metaphysical categories, (5) divine finitude, and finally (6) whether a finite God is necessarily part of a larger, more worshipful whole. After each of these discussions I will print responses which Ford wrote to the penultimate draft of this paper, followed by my own ad hoc comments on his responses.

Let me begin with a clarification of the contrast intended in claiming God is not to be identified with the ultimate principle of creativity. The alternative I shall defend is not that God is to be identified with creativity. Theravada Buddhists might defend this, arguing the only ultimate reality is the ceaseless flux of forms having neither worshipfulness nor character apart from the train of evanescent patterns.

My own alternative is the conception of God as creator of everything determinate, creator of things actual as well as of things possible.1 Apart from the relative nature God gives himself as creator in creating the world, God is utterly transcendent. The why and wherefore of the original creative act is mysterious, as Ford notes. But relative to the world as creator God is present to each creature in his creative act giving determinate being; and the world itself is a normative expression of the creator, undetachable from his creative reality. The creator, the act, and the expression form the rudiments of a philosophical trinitarianism.2 In contrast to God’s ontological creativity we can distinguish the cosmological creativity exercized by creatures constituting the world. With Whitehead we can agree the course of the world is characterized by events of harmonizing multiplicities into unities and that the being of the event is the processive becoming of the unity; we can accept Whitehead’s categoreal obligations for this process of cosmological creativity. What I call cosmological creativity, the only sort Whitehead acknowledges, is a descriptive generalization of the character of events; the reality of the events is accounted for with the ontological creativity of God the creator.3 God is the immediate creator of the novel values or patterns by which an event is constituted as the harmonizing of a multiplicity. Since the real being of an occasion is the becoming of a harmonized integration of the multiplicity, its components stem either immediately from God or from what it prehends; since what it prehends are other occasions, themselves analyzable into novel and prehended features, it can be suggested that every feature at some time in the present or past is or was a spontaneous novel pattern or value immediately created by God. Thus God is the creator of every determinate thing, each in its own occasion of spontaneous appearance. In contrast to God’s ontological creativity, cosmological creativity is the descriptive fact that the spontaneity in occasions brings unity out of multiplicity.

The point of this sketch of an alternative to Whitehead is that many of the virtues advertized for his conception are also possessed, sometimes more satisfactorily, by the alternative, as will be illustrated in topics discussed below.

Ford

Despite his protests to the contrary, it does seem to me that Professor Neville identifies God with creativity, provided we make allowance for the different ways creativity functions within diverse metaphysical options. To be sure, within Whitehead’s philosophy creativity functions in the pluralistic manner Neville suggests the Theravada Buddhist might want to identify with ultimate reality, but ordinarily when creativity and God are identified, creativity is given a transcendence unity. Being-itself is one, though there may be many finite beings which somehow participate in it. Both being-itself and creativity represent the power of being, that by which all actualities exist, though in many philosophies being-itself is conceived as uncreated and creative of others, while for Whitehead creativity is self-creation. Precisely on this point Neville is closer to Whitehead, for his creator God creates himself insofar as he is in any way determinate and actual. Apart from the creative act, this creator God is utterly indeterminate, acquiring determination through the creation of the world. Neville’s God is the supreme instance of creativity, a single everlasting concrescence whose concrete character is constituted by the many individual acts of “cosmological” creativity in the world.

If Neville accepts “cosmological creativity, the only sort Whitehead acknowledges,” we may well wonder what role “ontological creativity” has to play. Insofar as it can be rendered intelligible within his view, it has the same characteristics of self-creative unification the lowly “cosmological” creativity exercises. Moreover, it appears quite superfluous, since “cosmological” creativity can account for both the being of actualities and of God, as well as the ways in which God creates the metaphysical principles, the values the world strives for, and the unity of the world.

Neville

The distinction I would draw between ontological creativity and cosmological creativity is this. Cosmological creativity creates a one out of a previously real many; the new one created adds to the initial many and the process of cosmological creativity must continue by producing yet another one. Ontological creativity creates determinate things, both unified and complex, out of nothing; nothing determinate in the world, no antecedently given plurality, can be said to exercize ontological creativity because its own elements would enter into its production. I agree with Whitehead and Ford that God gives himself his determinate nature in creating, but this act is eternal, not everlasting in time. God’s production of his nature out of nothing is by no means the same as a Whiteheadian God’s creation of his nature out of the simple eternal objects. Whitehead’s God is cosmologically creative, using the simple eternal objects as initial data; I conceive God as having no initial data. Ontological creativity is not superfluous because it can account for cosmological creativity: cosmological creativity cannot account for itself because it can give no reason why creativity relates many and one (Whitehead’s Category of the Ultimate; see ibid.); ontological creativity would also account for the origin of eternal objects, something Whitehead’s God must accept as inexplicable initial data.

1. Human independence or ontological freedom from God is the virtue most often appealed to in the Whiteheadian conception of God, standing first in Ford’s list of virtues. The point is: because God is not identified with creativity as such, having only his own specification of it (other finite individuals having their own specifications of it), men have their own independent being, underived from God, however interdependent God and the world are in other respects. And because being in this case means a specific act of creativity, harmonizing a given multiplicity into the individual’s own concrete self, the independent being is independent self-determination, or freedom. Whitehead notes God’s influence on other actual occasions with the doctrine that God contributes in the initial phase of concrescence a value orienting the subjective aim of the occasion; in later phases the occasion can modify the subjective aim according to self-determined emphasis.4 Allowing all this for a moment, I want to point out this kind of freedom is a mixed blessing.

Whitehead must acknowledge God to be an external limit on human freedom, just as other external things are limits to our freedom. All objective things limit freedom in that they are given as initial data required to be harmonized in the prehending occasion’s concrescence. God’s datum is so important as to determine the initial state of the subjective aim. Whereas finite occasions do determine themselves, still God is like a mammoth Jewish mother, structuring all possibilities and continually insisting on values of her own arbitrary choice. In the long run there is a metaphysical guarantee, considering creatures’ immortality in God’s life, that no one can damn himself, and the possibility of self-damnation seems to me a touchstone of freedom, beyond the therapy of chicken soup.

The Whiteheadian answer is that the limitations contributed to an occasion by the world and by God are not negative, in any sense limiting freedom, but rather are positive values; limitation is essential to value. I accept that limitation is essential to value, but emphasize that freedom for Whiteheadians is supposed to be an occasion’s own creativity in determining his own final limitation within the range of possibilities inherent in the initial data. That is, an occasion chooses what limitation or value he will become, given the alternate possibilities for harmonizing the initial data. Insofar as God determines that value through the subjective aim in the initial data, the alternatives for the occasion’s own choice are diminished. Even if there is always a residue of self-determined emphasis left to the occasion, the function of God is still to force-feed a man’s intentions just as other men do.

The way to get around this objection is to say God’s contribution of possibilities and values is somehow identical with the occasion’s process of self-determination. But this would require the denial of the ontological independence of God and finite occasions. If God’s contribution of a spontaneous value defining an occasion’s becoming is identical with that occasion’s free adoption of the value, then for God to create the value there is the same as the occasion being self-determining. We could claim a man’s choice is determined by another in this case only if we said in fact that God’s being as creator is other than the man’s free process as creature. The conception of God as creator denies such an ontological difference, although Whitehead’s theory must hold to it. The problem for the creation view, admittedly, is to articulate the right sense in which God is not ontologically distinct from creatures and yet is their creator, ontologically independent of them.5

From the standpoint of religious and ethical experience I submit both human self-determination and divine determination of men are felt in the same acts. Furthermore, as Job found out, it is misleading to interpret God’s control of things on the model of a super-creature’s control of things.

Ford

I cannot agree that God functions as an external limit on creaturely freedom, for his role in concrescence differs from that of all other actualities. Each concrescence is the unification of the many actualities of the past actual world it confronts, but God is not just one more item in that world to be unified but the means whereby that unification can occur. As metaphysical stability of the universe God is incorporated into every concrescence, but that which renders any and all freedom possible is hardly an external limit upon it. All other guidance which God provides an occasion may be prescinded from in the course of the modification of subjective aim. Without an initial aim from God to direct the process of growing together there would be no way for the nascent occasion to become active, to have any basis of activity through which it could choose, but through its choices it can modify that original aim in any way consonant with its obligation to unify that particular actual world, which does impose external limits on its freedom. The occasion’s own choice cannot be depleted by the initial aim if that aim is what makes all choosing possible, and if that aim does not restrict its subsequent modification. We must remember that this is a process view of self-hood, for there is not first a self which chooses in accordance with some restricted initial aim, but a self which comes into existence through its choices, and whose origination must be explained. There are differing ways of conceiving the initial aim—e.g. as a graded set of alternatives embracing all the possibilities open to that occasion, or as a single aim sufficiently rich and indeterminate that all possible outcomes for that occasion are either diminutions or concretizations of that possibility—but these differing interpretations can preserve the complete freedom of the occasion with respect to its prehension of God.

Neville’s alternative, holding that God is not ontologically distinct from his creatures, illustrates nicely what would have been the case had God in his primordial envisagement decided upon metaphysical principles whereby all creativity would be exercised by him, i.e. if God had primordially decided not to create a world (distinct from himself). On a substance view it would be possible to hold that God creates the self which then acts on its own, but Neville wants to hold that the creature’s activity is also part of God’s creation. The creature lacks the freedom of self-creation, for it can exercise no being on its own.

Neville

I agree that in one sense God is not an external limit on human freedom, the sense in which he creates the metaphysical structures according to which human activity, as any activity, must take place. But the sense in which he is an external limit as other men and physical factors are external limits is in his being prehended among the initial data as a lure for feeling. According to Whitehead this lure is necessary for subjective aim to have an orientation in the nascent concrescence. But by the same token it is necessary for there to be a physical world, and the particular value God urges is just as arbitrary as the particular state of the antecedent physical world. It is sometimes said that God persuades as a final cause rather than coerces as an efficient cause. But this distinction makes no sense in Whitehead’s view. God’s value enters the occasion as an initial datum just like all the other data, and in this sense is an efficient cause. His value is a lure subjectively felt through the concrescence, but then so are the values of the other data. The other data’s values might be negatively prehended before the satisfaction, but then so can God’s. God’s value might be greater than the value of any finite occasion in the past, but what does this mean other than that the prehending occasion ought to aim toward it? If it means the divine lure is automatically more commanding to finite feeling than other valeus, then God is a greater limit on freedom than items in the physical world. If it means only that the divine lure is one among several values the prehending occasion might objectify, the occasion having completely free choice to choose the lesser value, then God is an external limit exactly in the same sense other things are.

I admit creatures lack the power of ontological self-creation; rather, God creates them, as many religious traditions including the Christian have claimed. But they do have cosmological self-creation, or self-determination. Their freedom consists in determining their own character relative to the determinate character they bring to decision, not in creating their own determinateness.

2. Concerning a creature’s intrinsic significance, the second of the virtues Ford cites for Whitehead’s view, an analogous objection holds; if the value the creature attains is contributed forcibly by an ontologically independent God, its significance is intrinsically located in actuality but extrinsically derived and determined. Ford’s argument itself focuses rather on a creature’s intrinsic contribution to value in the universe as preserved by God; without ontological independence our experience could neither add to nor detract from God’s. But ontological independence is not the issue: a creator God who creates a man intrinsically possessing such and such a value has precisely that value in his creative experience; were he not to create that man he would lack it. The intrinsic significance of creatures is strictly correlative to the values in God’s experience, on the creator view, and this is so whether the value comes to be actualized through the creature’s own choice or through blind antecedent determination. Since God’s creative act creates temporal determinations and is not temporally determined itself except in specific reference to temporal things, the issue of a creature’s adding something to God’s experience is meaningful only from the creature’s point of view. And from that point of view God is not specifically creator of such and such a valuable creature until it temporally comes to be.

Ford

Neville recognizes that without ontological independence our experiences and actions cannot enrich divine experience, but argues this issue is only meaningful from our (temporal) point of view. Of course, it is only from our point of view that the religious significance of human work is apt to be raised, but I see no reason why the distinction between the temporal and the non-temporal is necessarily relevant to the issue at hand. Either God’s own activity includes everything he can possible experience, or that experience can be enriched by the activities of others, and it makes no difference whether that activity is temporal or not.

Neville

To speak from a temporal point of view is admittedly an abstraction from the concrete whole. In the larger view I would claim “God’s own activity includes everything he can possibly experience,” and would deny, where Ford wants to affirm, that divine experience can be enriched by the activities of others apart from the divine activity.

But then I would claim the world and we are not apart from God’s activity; rather there is a coincidence of divine ontological activity and finite worldly activity in which both can be free after their fashions. We are of significance for God precisely because we are not apart from his activity.

3. Concerning evil, the Whiteheadian view indeed makes finite actual occasions responsible for the evil resulting from their own choices, moral or submoral. Of course, to the extent men’s choices are hedged in by divinely urged possibilities and values, as argued above, the choices can hardly be said to be men’s own; they are rather forced by God. But suppose evil is chosen only by men in independence from God. Why should we want in the first place to exempt God from responsibility for evil? Because of an antecedent commitment to God’s goodness. But to deny God’s responsibility by denying his causal agency is not to lend support to the doctrine of divine goodness; it only strikes down a counter argument. And the price of this move is to make the actual course of events irrelevant to God’s moral character; this goes counter to the religious feeling that God’s moral character is revealed in events, for better or worse. Furthermore, it makes the doctrine of God’s goodness itself an ad hoc hypothesis of the metaphysical theory, not something learned from experience. If God’s primordial decision regarding graded values and limitation in general is at root arbitrary, as Whitehead says it is, then it is only coincidence if God is metaphysically good, this being an arbitrary decision God makes in determining the metaphysical principles to which he must conform. Although Ockham’s razor is a dangerous weapon, I think the simpler doctrine would be that God, if he is to be judged by moral categories (remember Job), is just as good as experience shows him to be and no more. God is a good creator insofar as his creation is good, and beyond that there is no reason to judge. This should be admitted whether or not one maintains he creates the whole world or only the metaphysical principles (Whitehead’s position).

Ford

God is a good creator insofar as his creation is good, but on Neville’s principles he is also as evil as his creation is evil, and to that extent not deserving of worship. God’s goodness is hardly an ad hoc hypothesis, since it is intrinsic to any meaning of divine perfection we wish to defend. Nor is it mere coincidence that he is good, since his primordial decision determines (creates) what goodness is. Nor is this devoid of all experiential basis, for our human intimations of goodness are derived from God’s goodness revealed through the general evolutionary advance into richer complexity of order, in the moral aspirations of mankind, in the providential history of God’s interaction with man (e.g. in the life of Israel culminating in Christ), in personal religious experience of peace. The actual course of events is not irrelevant to God’s moral character, but neither is it an exact reflection; rather it is its creaturely, unfortunately imperfect, actualization.

Neville

To connect worshipfulness with moral goodness is a mistake, as Job found out. The numinous does not entail moral goodness. Divine perfection does not always mean goodness; I suspect its root meaning is supremacy. So, Plato’s form of the good is normative for all finite things, but not necessarily good itself; the creator of all things is supreme but not necessarily perfectly good. Especially, the creator of goodness, which Ford admits God to be, no more has to exemplify that standard than his world does; goodness is an ideal for finite things, and perhaps no more.

4. I agree with Ford in singling out Whitehead’s statement that God’s “conceptual actuality at once exemplifies and establishes the categoreal conditions” (PR 522). This is what Whitehead meant to say, I believe, and Ford is acute to show this renders a valid sense of actuality; God’s primordial nature is a result as well as the reality of decision. But I also believe the doctrine is untenable, and that Whitehead is mistaken. It is the character of a process of concrescence that at any phase short of the final satisfaction the unity of prehensions is partly indeterminate; before the satisfaction, then, the final satisfaction cannot be determinately exemplified. Especially, it cannot be said that the metaphysical categories are normatively binding on what is possible for God before they achieve their satisfactory determination. It might be countered that the metaphysical principles are determined in their full extent in the next-to-initial stage of God’s primordial envisagement, and that later stages are more determinate resolutions of possible relations within possibilities left open by the metaphysical principles. But in this case there is either a reason or no reason why God decides on the metaphysical principles; if there is a reason the principles are normative in the initial phase of God’s decision, and are therefore uncreated; and if there is no reason, the principles being ultimately arbitrary as Whitehead says, then they do not determine the possibilities in the first move from the initial stage of envisagement to the next in which the principles appear, and that first move does not exemplify them. It is possible to say, as the doctrine that God is ontological creator does, that God creates the determinate metaphysical principles or categoreal conditions; indeed, Whitehead is right in saying anything complex is the result of decision, in this case divine decision. Furthermore, the principles describe God in the sense he is the God who creates a world exhibiting these principles, including those articulating his created relation to the world. But it makes no sense to say the principles are norms for the concrescence of God’s primordial decision before they are created. Whereas the metaphysical principles determine the difference between possibility and impossibility for finite occasions’ concrescence, and the categoreal obligations are in fact rules for concrescing, God’s primordial creation of the principles cannot be called a concrescence in any way determined by the principles created.

Ford

Neville correctly (and quite acutely) observes that God’s primordial envisagement cannot have phases, for any early phases could not exemplify the metaphysical principles the envisagements is in process of establishing. I question, however, whether phases of concrescence are needed in a purely conceptual actualization, for the primordial envisagement is not the integration of already existent possibilities but the creation of possibility from that which is barely distinguishable from nonentity. Phases are needed for the integration of physical prehensions of already existent actualities, for the operation of negative prehension, for conceptual derivation from physical prehensions, for the integration of physical and conceptual prehensions, none of which apply to a purely conceptual actualization, though necessary for physical actualization. The categoreal obligations, and their explication in part III of Process and Reality, are designed to account for physical actualization, and cannot without revision be applied to conceptual actualization.6 Nevertheless, the primordial envisagement can properly be called a concrescence, for it is the act of unification creating possibilities. Possibilities can exist (or subsist) only as inter-related, as commonly exemplifying that which is necessary. Logical possibilities must at least be internally consistent, while all possibilities capable of actualization must exemplify the metaphysical principles.

Neville

I suspect phases are necessary for a conceptual actualization if there is more than one level of complexity, i.e., a complexity containing complexities instead of indeterminate simples. This aside, even if there is only one conceptual concrescence, the principles either are normative for it (and not its result) or produced by it (and not exhibited in it).

5. Let me repeat my appreciation of Ford’s demonstration of God’s conceptual infinity on Whitehead’s view, and the peculiar actuality this entails. This takes most of the starch out of the usual attacks on the finitude of Whitehead’s God in his consequent nature. It should be noted, however, that if one rejects Whitehead’s account of freedom, of the intrinsic significance of finite occasions, and of evil, as I have urged, much of the reason for saying God is finite in having a separate specification of creativity is taken away.

Furthermore, concerning the infinite side, there is a theoretical difficulty in saying whether the primordial decision is once accomplished and ever after objectively immortal or is rather everlastingly concrescing, never complete. Whitehead says both, and Ford has quoted both passages (Process and Reality 378, 47). I will put this theoretical difficulty aside here and only point out that the real onus of the charge against alleged divine finitude is the subordinate status a finite God would have relative to the whole including him plus the other ontologically independent beings.

Ford

Most of Neville’s comments on this point have already been discussed, but it should be pointed out that there is no inconsistency between Whitehead’s statements that the primordial decision is a created fact” (PR 46) or “an actual efficient fact” (PR 48) and his claim that it is “always in concrescence and never in the past” (PR 47). The primordial decision is a completed fact, but only in a non-temporal sense, much the same way an act of postulation completely, but non-temporally, determines all the theorems which could ever be deduced from that set of axioms. It is a basic mistake, however, to treat this conceptual actualization as if it were a temporal occurrence, as occurring sometime in the deep dark past. For a temporal perspective, this conceptual concrescence is continually unfolding novel possibilities without end. I have explored these matters in considerable detail in a forth-coming essay on “The Non-Temporality of Whitehead’s God.”

Neville

Whitehead said, “unfettered conceptual valuation, ‘infinite’ in Spinoza’s sense of that term, is only possible once in the universe.” The next clause, which Ford left out of his quote and which is grammatically incomplete, is, “since that creative act is objectively immortal as an inescapable condition characterizing creative action.”7 I construe this to mean, if not that the act took place in the deep past, at least that it is antecedent to any temporal occasion and therefore an objectively immortal completed fact. If it is objectively immortal and completed, it cannot still be in the process of concrescence.

6. Ford is correct God is not finite with respect to creativity in Whitehead’s scheme, since creativity is indeterminate apart from concrete specifications. He is also correct God’s conceptual nature excludes no possibility or achieved value; God feels the achieved value of every finite occasion with the same subjective form with which the finite occasion in its satisfaction feels it. But God’s finitude does contrast exclusively with the subjective process of concrescence in each temporal occasion. This is required for the mutual ontological independence of divine and temporal free decisions. Whereas in his consequent nature God might contain the value of the whole world, he in no way contains the creative activity of other creatures. The ontological whole includes God plus the world.

Ford’s apt description for God plus the world, ontologically considered, is the “solidarity” of God and world in the creative advance. There are marked similarities to Hegel’s Absolute Spirit. My question is whether the solidarity of the advance is not more divine, more worshipful, than Whitehead’s God. Hegel would say yes. By virtue of the very solidarity, God and the world are mutually dependent, and religious experience seems to prefer the relatively more independent. Whitehead could counter that his God, and not the world, is the creative source of the metaphysical principles, of all relevant possibilities, and of all possible values, maintaining the achieved values against loss. But the answer to this is that the complete creative advance is creator not only of all God’s contribution but also of the concrete achievement of finite value in the temporal decisions. There may be difficulties with the quasi-pantheism of the claim that the creative advance is most divine, or with Hegel’s Absolute Spirit. But pantheism has a solid footing in religious experience. In short, I think nothing short of the ground or principle of the whole of things is supreme enough to be worshipped. Professor Vaught is right.8

Ford

Neville thinks that only the “solidarity” of (Whitehead’s) God and the world is supremely worthy of worship, and should properly be called God, not that part of the whole Whitehead points to. Insofar as this solidarity also includes elements of imperfection, conflict, evil, triviality pervading creaturely achievement, I disagree. That which is supremely worthy of worship is that which is the unfailing source of value and that which is able to redeem and transform our imperfect achievements into a unified experience of beauty, thereby granting us that peace which passes understanding. Such is God in interaction with the world, preserving its independent integrity.

Neville

Again I protest the assimilation of worshipfulness to admirable moral character or redemptive service. The solidarity of the creative advance is ontologically superior to Whitehead’s God. For my own part, rejecting Whitehead’s conception of God I would reject his interpretation of the solidarity of the creative advance. On my view, God the creator and the world containing evil are not reciprocals on such ontological equality as they are in Whitehead’s system; I would say we worship the creator both transcendent of us and creatively present in us. As to redemption, if experience reveals that God does indeed redeem, create beauty and bring peace, then God is to be worshiped as the supreme creator of those things, as he is creator of all things. If God creates evil and suffering, our worship, although not our moral sensibility, still says, Blest be the Name of the Lord.

Notes

1 This is elaborated in my God the Creator (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968).2 The theological implications of this are pursued in my “Creation and the Trinity,” Theological Studies, XXX (1969), 3–26.

3 The distinction between ontological and cosmological matters, relative to Whitehead, and the interpretation of his categories as empirical generalizations are elaborated in “Whitehead on the One and the Many,” The Southern Journal of Philosophy, VII (1969–70), 387–393.

4 Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: Macmillan, 1929), p. 74. Hereafter cited as PR.

5 See God the Creator, ch. IV.

6 Here see my (Ford’s) “Whitehead’s Categoreal Derivation of Divine Existence,” The Monist, LIV (1970).

7 PR 378.

8 See Ford’s note 36.

Posted April 15, 2007